Growing up in the windswept Texas Panhandle during the Great Depression, Harley Redin never imagined he’d make it into the Basketball Hall of Fame. But this week, the Plainview native was honored alongside former NBA stars like Steve Nash and Jason Kidd.

That’s because seventy years ago, Redin revolutionized women’s basketball.

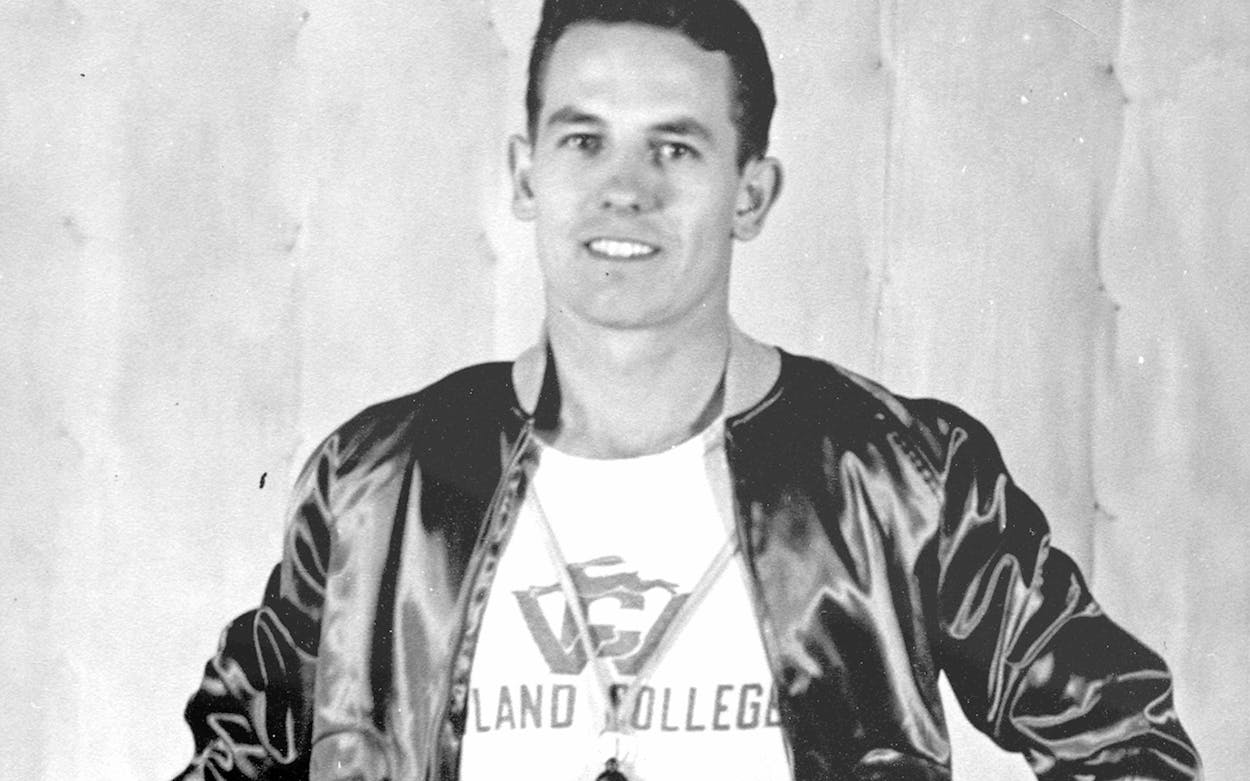

In 2013, I wrote about Redin, who in the fall of 1946, more than seventy years ago, was the sole staffer of the physical education department at Wayland Baptist College, a school of just six hundred students in Plainview. Redin, who was then 29 years old—a wiry, brown-eyed Marine who had flown more than fifty bomber missions over the South Pacific during World War II—got convinced by a number of young women at the school to coach a women’s basketball team. They named themselves the Wayland Baptist Flying Queens. The daughters of Panhandle farmers, machinists, water salesmen, and railroad workers, the young coeds who joined the Queens had been playing basketball since they were little girls, practicing old-fashioned set shots at wire rims nailed to tree trunks in their backyards.

They weren’t expected to do much—maybe win a few games against other area colleges and junior colleges. But what happened next turned out to be one of the great stories in the history of American sports.

From November 1953 until March 1958, the Queens won 131 straight games, which remains the record to this day for the most consecutive wins in collegiate women’s and men’s basketball history. During that streak, they also won four national Amateur Athletic Union championships, beating much more experienced teams made up of older veteran players.

After I wrote the story about Redin and his players, who overcame seemingly insurmountable odds to create a basketball dynasty, there was a campaign among many of Redin’s ex-players to have him named to the Naismith Memorial Basketball of Fame in Springfield, Massachusetts. After all, he had laid the foundation for modern women’s college basketball. His coaching techniques had helped transform the women’s game. At one point, he had even persuaded members of the Harlem Globetrotters to teach his lily-white players better ballhandling skills.

Earlier this month, Redin, who’s now 99 years old, was finally recognized by the Hall of Fame, receiving the Naismith’s 2018 John W. Bunn Lifetime Achievement Award. Although he and his wife Wilda, who’s 97, did not attend the ceremony, his two sons, the president of the university, and a couple of ex–Flying Queens flew to Springfield for the occasion. While much of the media attention was directed at former NBA stars like Steve Nash and Jason Kidd, who were enshrined into the Hall of Fame, Redin got one of the biggest laughs of the night. In his speech, which had been filmed at his home, he talked about his early years playing basketball in Silverton, a tiny town in the Texas Panhandle, during the Depression. “We were so poor, we didn’t even have air for the basketballs,” he said.

I called Redin the other day. “Hey there, young man,” he said. “I’d have you say hello to Wilda, but she’s at the beauty shop.” I asked how he was feeling, and he replied, “I’m still kicking—barely.” He told me he almost never leaves the house these days, not even to go watch the Wayland Baptist Flying Queens’ home games, which he used to attend without fail. “I miss the girls flying up and down the court, dribbling like crazy, taking those long jump shots,” he said. “Boy, the game is fast compared to my day.”

I reminded Redin that he is, in part, the reason the women’s game is so fast. (In his era, there were six women on the court for each team: two on the offensive half of the court, two on the defensive half, and two “rovers,” who were allowed to roam the entire court. Redin was one of the first proponents of five-woman, full-court basketball.) Redin said, “Oh, I don’t think so. It would have happened with or without me. I wasn’t that big of a deal.”

“You were a big deal, all right,” I said. “You still are.”

“Young man, you’re nice to say that,” said Redin. “I sure do appreciate it.” He paused. “Well, I guess I ought to hang up now and get on with my day.”

And he did.

- More About:

- Sports

- Basketball