“Last night felt like the end of something,” Richard Linklater said as we sat outside his Austin production office in mid-March, on the day Donald Trump declared the coronavirus pandemic a national emergency. For weeks I’d been told the Oscar-nominated director wouldn’t be available for an interview until after South by Southwest, but officials had called off that mega-event a week earlier. Unexpectedly, he was free.

The evening before, we’d both attended the Texas Film Awards, the annual big-dollar fundraiser for the Austin Film Society, of which he’s the founder and artistic director. The city had yet to issue a stay-at-home order or ban large gatherings, so the group decided that the show would go on. Being there felt like fiddling while Rome burned; any of the 250-plus of us present could have been a vector for COVID-19. Gallows humor abounded, along with chuckling at the novelty of exchanging elbow bumps instead of handshakes. We didn’t know then that many of us would soon be isolated for months at home.

The crowd’s bonhomie served as a reminder that Linklater owes his career to having drawn together a community of creative people who supported and promoted his work at critical junctures. And the social distancing we’ve all practiced since then starkly reminds us that Linklater has made a career of immortalizing “the poetry of day-to-day life,” to borrow a line from Before Sunrise. His most celebrated works—such as Boyhood, Waking Life, and Slacker—ask us to appreciate how even seemingly minor encounters contain the power to dramatically alter our futures. Watching his films while we cloister ourselves in our homes, it’s hard not to feel a sense of loss for all that we’ve had to set aside during this lockdown.

Right after he and I talked on that breezy Friday afternoon, Linklater headed with his family into his own COVID-19 quarantine at his farm, in Bastrop County. Out there he’s been working on several projects in postproduction and making calls to pitch another longtime dream. The man mistaken early on for the sort of apathetic coffee-shop philosopher that his improbable breakthrough film, Slacker, helped make synonymous with Austin remains as driven and ambitious as ever.

It’s been 35 years since he started a nonprofit that transformed the Texas film industry and turned Austin into a television and movie production hub. It’s been 30 years since the debut of Slacker, which established him as a singular voice among a new generation of independent filmmakers. And in late July the man who was once asked to speak for a generation of American twentysomethings turns sixty. It’s a milestone birthday, amid a year of professional milestones, that—despite the uncertainty that has pockmarked 2020—feels like far from the end of something.

To get a grasp on Linklater’s youth in Houston and Huntsville, watch his most acclaimed film, 2014’s Boyhood, which was nominated for six Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. Linklater drew heavily from his own life in shaping the story of its central character, Mason. After his parents divorced when he was very young, Linklater lived primarily with his mother, a college professor. His dad worked as an insurance underwriter. At school he often daydreamed, staring out classroom windows. And he, too, received both a shotgun and a Bible as gifts one year. “Rick makes movies about our childhood,” jokes Tricia Linklater, one of his two older sisters. “My sister and I went to therapy like everybody else.”

For hints of what his high school years were like, look at Pink in 1993’s Dazed and Confused, which is set in a Texas town on the last day of class in 1976. Played by Jason London, Pink is a jock who resists authority and is as comfortable palling around with the brains and stoners as he is with fellow members of the football team. “Rick’s that weird anomaly, the type of person who seems to fit in with every crowd he’s in,” says actor Ethan Hawke, a close friend who has appeared in 8 of Linklater’s 21 features. “Because he’s so unjudgmental. He really likes people.”

Baseball, which Linklater had been playing since childhood, landed him a scholarship to Sam Houston State University, in Huntsville. As a teenager he thought he might play pro ball—that or become a novelist. He’d always liked movies, but he hadn’t watched many classics. Then, during his sophomore year of college, he saw Martin Scorsese’s masterpiece Raging Bull. What felt like his life’s calling came into focus. “That just got me thinking, ‘Oh, wow, film can do that?’ That’s when the film bug totally let loose on me,” he says.

Linklater began to see every movie he could. Before long, his creative output was adapting to his new passion. He remembers writing a short story that unexpectedly came to life visually in his mind—one moment a close-up, another a wide shot. “I was like, ‘I just need to get a camera,’ ” he says. “I’m realizing I’m a filmmaker. I’ve found my medium. Once I knew it, I never looked back.”

By mid-1981, he’d dropped out of college. A heart condition had prematurely ended his baseball career. “I might not be here today if I’d spent two more years playing ball, especially if I’d gotten the opportunity to kick around in the minors for a little while,” he says. He went to work on an offshore oil rig in the Gulf for a summer and decided to stay on instead of returning to school. When he wasn’t working, he was a regular at several Houston cinemas, including the River Oaks Theatre, where he consumed its lineup of art-house fare.

After getting laid off from his oil rig job, he made his way to Austin in 1983, drawn by the University of Texas’s vibrant film culture—five different movies might be screened on any given day on campus—and the cheap living afforded by a $150-a-month, all-bills-paid place. His grades weren’t good enough to get him into UT’s film program, but he took a couple of classes at Austin Community College. Chale Nafus, who taught film appreciation and history courses, remembers Linklater as a quiet student who wrote with a mature understanding of character dynamics and cinematography. “I wish I’d kept all of his papers,” Nafus says. “I had no idea at that time that he wanted to make films. I thought he was going to be a very good film teacher or critic.”

Linklater had always been a mediocre student, unable to concentrate well enough on his textbooks to retain the information, but he excelled in these courses. His success puzzled him at first. “Why am I killing the curve for everybody else?” he remembers thinking during his short time at ACC. “Oh, it’s because I f—ing know what I want to do in this world.”

Thanks to a tidy sum Linklater had saved from working offshore and his facility for living inexpensively, he was able to shut out anything that didn’t advance his filmmaking dreams. He remained blissfully unemployed for much of his first four years in Austin and devoted nearly every waking moment to his goal. He bought a Super 8 camera and taught himself to make short films. He read every book he could find about the work of directors he admired, like Paul Schrader and Andrei Tarkovsky. He wrote scripts, took acting classes with a local coach, and saw hundreds of movies a year.

“All I wanted in life was to do what I wanted to do,” he says. “We had set up this ideal world where we just got to play. I wanted to create a world of movies and passionate people who love what I love. And that’s what kind of came about.”

The history of the past several decades of Texas filmmaking would be vastly different were it not for Linklater’s insatiable cinematic appetites, which quickly grew larger than Austin could satisfy. After he’d been in the city a couple of years, he realized that the UT film series generally cycled through the same set of seminal movies. He wanted to see more obscure fare, stuff that wasn’t available even on the VHS tapes that film geeks at the time would circulate among themselves. That hunger is the reason the Austin Film Society was born.

When Linklater learned he could rent sixteen-millimeter film prints for about $150 from independent film distribution and licensing houses, he figured he could cover the cost by charging people a couple bucks each to attend screenings. That would allow him to see anything he wanted. He and his roommate Lee Daniel, who was an assistant cameraman for a local production house, convinced Scott Dinger, who ran the Dobie Theatre, next to the UT campus, to let them host a midnight series the first weekend of every month, starting in October 1985. Louis Black, the editor of the Austin Chronicle and a fellow film nut, offered free ad space to promote it. Black, who went on to cofound SXSW, had met Linklater at the rock club Liberty Lunch earlier that year. “This kid came up to me because he’d read an obituary I’d done on Sam Peckinpah,” Black remembers. “We began talking about film, and he had a real hunger and a real knowledge.”

The first program of what soon became AFS was a collection of experimental shorts. Linklater and Daniel chose a provocative title—“Sexuality and Blasphemy in the Avant Garde”—and blanketed the area near UT with flyers that featured an image of a man’s hand cupping a woman’s breast, from the 1929 surrealist film Un Chien Andalou. The flyer caught the attention of another young cinephile, Brecht Andersch, who attended that first-ever screening. It nearly sold out the roughly two-hundred-seat theater late on a Friday night. “I just had a sense that it was deep, it was rich,” Andersch says. “It was something a little bit more intense than a normal film screening.” Soon after, he offered to help Linklater and Daniel program and promote screenings and moved into their West Campus apartment.

“He’d turn on his Super 8 camera, run out in front of it, and act out a scene, then run back and turn it off. I thought, ‘You can’t stop a guy like this.’ ”

Over the next few years, as AFS started to host screenings regularly and attained nonprofit status to apply for grants, others were drawn into its orbit. Like East Texas native Clark Walker, who had spent two years in Los Angeles trying to break into film production. On the very morning in 1986 when he moved to Austin, he spotted a flyer advertising a retrospective on French minimalist director Robert Bresson. “I’m like, ‘How does anyone in Texas even know who Robert Bresson is, much less is showing his films?’ ” Walker remembers. Later that day, he called the number on the flyer, and Linklater answered. “We got into a two-hour conversation about Bresson and transcendental film and Paul Schrader and Yasujiro Ozu and Carl Theodor Dreyer.”

During this same period, even as he ran AFS, Linklater began working on his first feature-length film. He handled every element of the production and starred in it himself. For some scenes, he recorded the audio on a Sony Walkman in his pocket, using a microphone threaded up through his shirt, and set his camera on a tripod. “He’d turn on his Super 8 camera, run out in front of it, and act out a scene, then run back and turn it off,” Walker says. “I thought, ‘You can’t stop a guy like this.’ ”

It took two years for Linklater to complete the 85-minute film, It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books. With little dialogue, it follows a nameless character, played by Linklater, as he travels from Austin to Montana and back to visit a friend. Many scenes linger on mundanities like Linklater’s character boiling water and taking money from an ATM. There’s a memorable moment where a shirtless Linklater fires a shotgun out his apartment window. “It’s not like I aspired to make films alone,” he says of this first effort. “I was really just feeling my way through the medium.”

Though Plow wasn’t the sort of film likely to attract much of an audience, Linklater impressed the small circle of friends who saw it. “I knew people in the UT film program, and they would argue all semester long just to make a short by the end of the year,” says film producer Tommy Pallotta, then a UT student who worked at the Dobie. “And here’s this guy, by himself, who made a feature out of Super 8 film. I was like, ‘Forget film school. I’m going to let this guy be my film school.’ ”

It wasn’t long before Linklater began to plot his second feature. The idea had come to him during a late-night drive between Austin and Houston about five years before. Why not make a film in which one brief episode leads to another, one character passing the narrative baton to the next as they cross paths? He’d never seen a movie like that.

Slacker wasn’t actually the first film to be composed of such linked vignettes. Max Ophüls’s La Ronde, released in 1950, and Luis Buñuel’s The Phantom of Liberty, from 1974, use similar structures (in markedly different ways). But Slacker was unlike anything U.S. audiences had seen before, not to mention far better than any movie shot with sixteen-millimeter film with a cast of mostly nonactors on a production budget of just $23,000 has any right to be.

That’s thanks largely to the community of collaborators that the film society had brought together by the time shooting began in the summer of 1989. Through those connections, Linklater gained cheap or free access to equipment—including a crane, a dolly, and a Steadicam—otherwise beyond his financial means. He also benefited from the technical know-how of Daniel as his cinematographer and Walker as the camera assistant. Both of them had spent far more time on film sets than he had.

He enlisted other friends, including Black, Pallotta, and Andersch, to play parts. Linklater couldn’t afford to pay the cast and crew—at least not until he’d sold the film—but he figured he knew enough willing participants who’d volunteer a day or two of their time and, bit by bit, he could shoot over several months. To feed everybody, he ran up the balance on his gas station card; Daniel remarked wryly that they were each entitled to a taco and a half every ten hours.

“It was definitely down and dirty. I was really burning through the credit cards. My folks ended up putting in about six grand. My sister went to an ATM at a crucial moment,” Linklater says. “Proudest day of my life was to pay back people who gave me money for that.”

Now widely considered a landmark of the early nineties independent film movement, Slacker initially had difficulty attracting interest. If it hadn’t been for the promotional tricks Linklater had learned running AFS, the movie might have ended up like Plow. It was rejected by several major festivals, including Sundance and Berlin, before getting its first U.S. public screening in the spring of 1990 at the USA Film Festival, in Dallas. Local critics didn’t care for it, but Linklater was buoyed by the positive reaction from the audience.

After the prestigious journal Film Comment ran an article about Slacker, Linklater called up John Pierson, a producer’s representative in New York who was well known in the indie film world for having secured distribution deals for Spike Lee’s and Michael Moore’s first features. Coincidentally, Pierson had just read the Film Comment piece the day before and was interested in seeing the movie. A few weeks later, Linklater sent Pierson a video copy, along with a letter in which he wrote that Slacker was “a definite crowd-pleaser for a particular niche of the population.” That population, he argued, wasn’t just the twentysomethings much of the film portrays but also “a slightly older audience with beatnik or hippie sensibilities—basically anyone in the entire post–World War II period that has felt at all marginalized or at odds with their society.”

Meanwhile, Linklater asked Scott Dinger to grant Slacker a theatrical run at the Dobie. The hustle the AFS crew demonstrated in turning out audiences for its screenings had impressed Dinger, even if he was dubious about the box-office prospects of Linklater’s film. He hedged his bets by agreeing to a four-week run but guaranteed no more than one screening a day. Linklater and company turned again to their AFS bag of tricks, plastering Austin with flyers and stickers. The Chronicle helped too, with a cover story raving about the film. When Slacker opened in late July 1990, the first 22 public screenings sold out. Dinger was soon giving the movie every available time slot on one of his two screens.

Linklater sent word of this success to Pierson, who’d been so impressed by Slacker that he’d shown it to Michael Barker, a UT graduate who was an executive at the distributor Orion Classics. “Back then, not that many people used the idea of a local launch,” Pierson says. “There are only a handful of examples of that working, and Slacker is such a good one. It’s really impressive.” Orion offered Linklater a $100,000 advance and about $50,000 to cover the costs of preparing the film for a 35-millimeter release. He took the deal, and the film’s extended eleven-week run at the Dobie came to an end while it was still doing strong business.

A slightly new cut of Slacker was accepted into the Sundance Film Festival in January 1991, and its nationwide theatrical release began the following July in New York and Austin, slowly rolling out in other cities into the fall. Slacker eventually grossed $1.2 million, an impressive figure for an oddball, microbudget movie. Linklater traveled to promote it and found himself speaking to interviewers more interested in painting him as a voice of Generation X—a term popularized by the title of a novel released that same year—than in his movie. They mistook Slacker for a documentary of Linklater’s life in Austin rather than the culmination of his nearly decade-long focus on filmmaking.

“I was just astute enough to say, ‘Oh, there’s a cultural spot available to me if I want it, to be a talking head about this generation,’ ” Linklater says. “But that’s not me. I just wanted to make my next film.”

On that 80-degree March afternoon at a patio table just outside his Detour Filmproduction office at Austin Studios, Linklater sipped water from a tall green plastic cup, often leaning back with one leg propped up on another chair. Sometimes he trailed off, speaking so softly that I was concerned my recorder wouldn’t pick him up.

When Linklater’s friends and colleagues speak about him, they often use the word “quiet.” Many praise his intellect, generosity, and work ethic. “He’s not the kind of person who’s ever gone out and partied,” says Pallotta, who went on to produce Linklater’s animated movies, Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly, and has written and directed a handful of his own films. “Rick’s the guy who’s standing in the corner, watching the guy who’s partying and taking center stage, and taking mental notes that he’s going to use later on in his films.”

Yet Linklater’s understated, easygoing manner shouldn’t be mistaken for a lack of confidence. The aplomb that helped him launch his career has never left him, and he has little patience for investing his energy in anything that doesn’t spring from his own interests. That’s why he turned down early opportunities to work his way up in the industry by starting as a production assistant on other people’s projects. “He’s focused on making his films, and you’re either with him or against him,” Walker says. “If you’re against him, he doesn’t have time for that.”

That surety in his vision comes across in his response to criticism. He sounds defensive as we discuss 1998’s The Newton Boys, the story of a Texas family of bank robbers that was the first of his films to be both a critical and a box-office disappointment. It’s evident that the commercial failure still stings—it was difficult for him to secure funding for several years afterward—but he stands by it as a “f—ing really great movie.” Walker, who cowrote the screenplay and argued against Linklater’s lighthearted approach to the material, calls it “a mess” that he’s proud of.

Linklater similarly stands by each and every one of his films, expressing no regrets—not even for casting right-wing conspiracy theorist Alex Jones in small parts in Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly. “I would [have had some regrets] if that had happened in the last ten years.” Linklater says. “But no regrets. Very fun, both times. I haven’t talked to him lately, and I can’t speak for this era for Alex, but I always found him really friendly, a lot on his mind. I kind of like people like that. The whole Trump era has been not good for him.”

The director is equally dismissive when I suggest that editors can have significant influence over films. Though he acknowledged feeling lucky to have worked with Sandra Adair (his editor since Dazed) and swears by her expertise, he emphasized that every decision about every frame is ultimately his. “That goes for every department,” he says. There’s a certain tension between Linklater’s espousal of the auteur theory—the idea that the director is the author of a film—and the intensely collaborative nature of his movies. Before each shoot, he favors weeks of rehearsal, during which he encourages the cast to help further develop their characters and refine the dialogue.

That approach caused friction between Linklater and some members of the Slacker crew. Clark Walker says that during production the crew thought of the film as a cooperative effort, not just “Rick’s film.” And in film scholar Alison Macor’s 2010 book, Chainsaws, Slackers, and Spy Kids: Thirty Years of Filmmaking in Austin, Texas, Daniel refers to Slacker as “the least auteur film ever made.” (Daniel and Linklater had a falling-out more than a decade ago, after working together on seven features. Daniel didn’t respond to several interview requests.)

Macor’s choice to use the quote as the title of her chapter about Slacker clearly irritates Linklater, who bristles when I bring it up. “That quote’s kind of a joke,” he says. “I think at the end of the line, they realized, ‘It’s kind of Rick’s movie, but we all got to participate in it.’ So that realization hit people in different ways, put it like that.”

Though that defiant belief in himself may have rubbed some of his collaborators the wrong way, it has also allowed him to progress through his career with little fear of failure. Fellow Austin filmmaker Jeff Nichols recounts an anecdote Linklater once told him about a producer who hired an outside editor to make his own cut of one of Linklater’s movies. Linklater told the producer, “I’ll let you do that, but take my name off of it,” and the producer relented.

“The point that he was trying to make to me was that the only power you really have is to walk away,” Nichols says. “It’s an industry that feeds on the desperation of filmmakers who desperately want to tell their stories, and that’s when they’ve got you. That’s when they can distort and manipulate the thing that you’re passionate about. But if you maintain the confidence that ‘if it’s not going the way I need it to go, I’ll just step back,’ that’s where all the power is.”

Last November, the Centre Pompidou, in Paris, honored Linklater with a retrospective exhibit. The museum also screened every film he’s ever made, including shorts, as well as his 2004 pilot episode of $5.15/Hr., a comedy that HBO declined to take to series. Curators highlighted how Linklater often plays with the element of time in his work. Four of his first five movies take place in 24 hours or less, and two others (Tape and Before Sunset) occur in real time. He famously shot Boyhood over twelve years to capture the real-life aging of its cast. And last year he finished the first segment of an adaptation of Stephen Sondheim’s musical Merrily We Roll Along, which will be filmed over the course of twenty years to likewise allow its cast to age along with their characters.

“I kind of get obsessed with forms first, and the story fills in around it,” he says. “I have characters and feelings that are looking for the right narrative form. So it’s the wedding of those two things. That’s the nature of what films are. They’re formal constructions. I have a line in Where’d You Go, Bernadette where she says, ‘I’ve got to inhabit a space before I know what it wants to be.’ That’s how I feel about every film. You’re feeling your way through how it should look and feel.”

Linklater’s most critically lauded movies tend to be the small-scale stories that grow out of that philosophy, films that focus on his fascination with the unpredictable ways that chance encounters with others can shape our lives. Foremost among those, perhaps, is the trilogy that began with 1995’s Before Sunrise, in which a pair of young travelers named Jesse and Celine (played by Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy) meet on a train and spend one long night together roaming the streets of Vienna. Inspired by an experience from his own life, Linklater sought to capture the sense of magic that comes with feeling a deep and immediate connection to another person. At the time of its release, no one would have predicted Sunrise would spawn two sequels, Before Sunset and Before Midnight, nine and eighteen years later.

After the setback with The Newton Boys in 1998, Linklater regrouped with 2001’s Waking Life, essentially a spiritual sequel to Slacker, which he and Pallotta shot themselves using digital cameras. It was the first feature film animated using a computer-aided rotoscoping technique developed by Austin animator Bob Sabiston. Linklater returned to the style a few years later with the Philip K. Dick science-fiction adaptation A Scanner Darkly.

“If there wasn’t so much suffering and bad news going on, I would be enjoying this. An introvert’s paradise. I don’t have to be anywhere. I can just work on my shit.”

But his best-known effort may be 2003’s School of Rock. It’s his biggest box-office hit (grossing $131 million worldwide), and it marked the first time he was a director-for-hire on someone else’s project. (He signed on when it was agreed that he could bring his usual methods to the casting and revision of the screenplay through rehearsals.) He enjoyed that experience well enough to take on another big studio-backed comedy, a remake of The Bad News Bears, a couple years later. The other projects he’s chosen are as varied as a documentary about UT baseball coach Augie Garrido; Me and Orson Welles, a period piece set in the 1930s New York theater scene; and Bernie, perhaps the most Texan of all his films, based on a 1998 Texas Monthly true-crime story.

During the past decade—in such movies as Before Midnight, Last Flag Flying, and Where’d You Go, Bernadette—Linklater has entered what he describes as his middle-aged period. Each of those films is about characters at midlife reflecting on their pasts as they’re forced to reckon with what they want for the future. It’s rich territory that poses new challenges. Before Midnight, in particular, was “the hardest movie I’ve ever done,” he says. “I think because it’s easier to make a film about falling in love or reuniting, rekindling love. But to make a film about staying in love?”

He lets the word “love” hang in silence for a moment, suggesting that he’s still reckoning with the question.

Though he never abandoned the Austin Film Society, Linklater did come to count more and more on others to run the organization while he was making films. AFS grew larger and more professionalized over the course of the nineties—hiring staff and beginning to award funding to up-and-coming directors through its AFS Grants program. After Austin’s Robert Mueller Municipal Airport closed in 1999, Linklater helped convince city leaders to turn a collection of old hangars into production stages and offices, called Austin Studios, and let AFS run it. The film society also saw through another dream in 2017 and opened its own cinema, which marked the first time in nearly three decades that AFS could screen films in its own exhibition space. Linklater programs and hosts films there when his schedule permits.

Each of these efforts required more money to sustain, but Linklater—who started AFS by selling $2 tickets just to cover the cost of renting, say, a Rainer Werner Fassbinder film—wasn’t thrilled when the star-studded, $1,000-a-plate Texas Film Awards were dreamed up as a revenue source in 2001. “It took me a while to adjust to the idea that there’s money in Austin now,” he told me during the cocktail reception that preceded this year’s mid-March event at Austin Studios. He’s come around to appreciating the film awards, which raise hundreds of thousands of dollars annually for AFS Grants and other filmmaker support programs. Still, attending the ceremony requires two things he hates: getting dressed up and giving speeches.

After sipping drinks and mingling at this year’s awards reception, the crowd made its way to Stage 7, the hangar turned production space in which the dinner tables and event stage had been erected. Linklater, who has been a vegetarian since his early twenties, was irked that the evening’s menu included braised short ribs. His most political film, 2006’s Fast Food Nation, is an adaptation of Eric Schlosser’s nonfiction best-seller about the exploitative underbelly of food industrialization. “There’s no way to eat meat and not be supporting animal cruelty,” Linklater says.

The gala had a good turnout, given the circumstances, though it wasn’t difficult to spot empty seats at many tables. Even before the program began, COVID-19 had stolen the evening’s spotlight. Three of this year’s four honorees—actors Shelley Duvall, Michael Murphy, and Kaitlyn Dever—had bowed out of attending and appeared via prerecorded video. The only honoree present, musician Erykah Badu, wore a hazmat suit to lighten the grimness of the situation.

When master of ceremonies Parker Posey stepped onstage, the band played a riff on “Low Rider,” a song that memorably appeared in Dazed, one of two Linklater films in which Posey had roles. “Thank you, Rick, for that iconic movie,” she said. Seated at a table near the middle of the room, Linklater raised his right hand into a peace sign, then made the “rock on” gesture. When he took his turn at the podium, he and Posey exchanged elbow, hip, and foot bumps in a playful dance while the band played Toto’s “Africa.”

After the honorees were recognized and the live auction was over—a $10,000 bid won a dinner for six with Linklater—the crowd rose to tramp back out to the reception room for the after-party. Linklater headed one table over to speak with Annie Silverstein, a former AFS Grant recipient who had participated in the film society’s annual workshop at Linklater’s Bastrop farm in 2015. He hadn’t seen her since then, and the script that he and other mentors had critiqued had become her first narrative feature, Bull, which was supposed to get a U.S. theatrical run in March, before the pandemic shuttered cinemas. (It has since been released to on-demand streaming.) He didn’t want to miss the opportunity to congratulate her.

The following week, I spoke with another young filmmaker whose career Linklater has likewise championed. Fort Worth director Channing Godfrey Peoples’s first feature, Miss Juneteenth, premiered at Sundance in January, and was released to streaming (its theatrical run was also halted by the pandemic) on the eponymous holiday. Like Silverstein, Peoples is a past AFS Grant recipient and had been chosen by the film society to workshop her script in Bastrop. A few years later, she returned to Linklater’s farm with an edited cut of Miss Juneteenth, and he gave her some feedback. “He’s an inspirational figure for me, especially as a Texas filmmaker,” Peoples says. “So there was a little bit of nervousness being there with one of the people who’s really inspired you. But I felt encouraged to embrace the uniqueness of my story and the way I was telling my story.”

Elevating other filmmakers was a goal that Linklater aspired to early on with the film society. Successes like Silverstein’s and Peoples’s have helped build the Texas film industry into something he scarcely could have imagined at the outset of his own career. “If you go back to the eighties, it would have been inconceivable to me that there would be a feature film made in Austin or nearby that you wouldn’t know about,” he says. “Now there’s so many, between the docs and the features. There’s so much going on, not only do you not know about the films, you haven’t met the filmmakers. It’s great. It’s a big community.”

When I called Linklater in mid-April, about a month into his Bastrop quarantine, he and Sandra Adair were hard at work editing his next feature, which they were doing remotely (ordinarily, they’d be side by side, making cuts). The film, Apollo 10 ½, draws heavily on Linklater’s childhood in Houston during the years of the Apollo space program. With Pallotta again as his producer, it’s being made with computer-aided rotoscoped animation, just as Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly were. (The technology has improved significantly since those films were made, as demonstrated by the Amazon streaming series Undone, which Pallotta executive produces.)

The Apollo 10 ½ shoot, at Robert Rodriguez’s Troublemaker Studios, in Austin, involved the extensive use of green screens, something Linklater has done little of during his career. He and Adair will spend months editing the live-action footage before their cut is turned over to the animators. Fortunately, they had finished shooting before the pandemic could shut down production.Like much of American business, the film industry had been at a standstill since late March.

The pandemic affected the Austin film ecosystem in other ways too. A week after the film awards, Austin Public Health notified AFS that at least one attendee had tested positive for COVID-19, and Nichols had also fallen ill with it a few days after attending the awards. (It’s unclear whether either person contracted the disease at the event.) Linklater; his daughters; his longtime partner, Tina Harrison; his father and stepmother; and Tina’s father had all stayed healthy out in Bastrop during isolation.

“If you go back to the eighties, it would have been inconceivable to me that there would be a feature film made in Austin or nearby that you wouldn’t know about.”

The coronavirus did further damage to AFS, however. Shortly after Austin stay-at-home orders forced the closure of movie theaters, the nonprofit announced that it was laying off all the hourly workers at its cinema and furloughed much of its full-time staff at least one day a week to adjust to the lost revenue. “It’s tragic,” Linklater says. “We’re not different than anyone else, so there’s none of this ‘Woe is us’ because everyone’s going through it. So why even talk about it, other than we think we’ll come back strong?” (In early May, AFS announced it was pushing ahead with its annual filmmaker grants.)

As he approaches his sixtieth birthday on July 30, Linklater doesn’t expect to ever retire from making films. He’ll be eighty when Merrily We Roll Along is finished, assuming all goes according to plan. He’s recently completed a documentary about criminal justice in Texas that evolved into a “deeply personal” look at his hometown of Huntsville, one of a triptych of films inspired by Lawrence Wright’s book God Save Texas: A Journey Into the Soul of the Lone Star State that are in production for HBO. He’s also producing a reality series for CBS All Access about animal rescue groups in Central Texas, which he says is “exactly 180 degrees opposite” of Tiger King, the popular Netflix true-crime documentary series set in the world of big cat collectors.

Other Texas-centric projects have been announced but remain in limbo, including a biopic of early-twentieth-century South Texas medical con man John Brinkley. “It’s a good Del Rio film,” Linklater says. There’s also a planned biopic of Houston stand-up comedian Bill Hicks. “That’s another one that’s been in the gestation wheel for quite some time and I’ve been chipping away at.”

After we finish our chat, he’s going to make another call in hopes of getting the green light for a limited television series about Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and other nineteenth-century transcendentalists. He’s been working on the script, with input from historians, on and off for the past twenty years. For now, he’s focused on the months of editing ahead on Apollo 10 ½. “If there wasn’t so much suffering and bad news going on, I would be enjoying this,” Linklater says of his temporary life of seclusion. “An introvert’s paradise. I don’t have to be anywhere. I can just work on my shit.”

Given that the creation of the Austin Film Society sprang from Linklater’s self-professed selfish desire to see movies he otherwise couldn’t, would AFS have come into existence today? Now anyone with a broadband connection anywhere in the world can access thousands of films, including much of the relatively obscure fare that Linklater once took great pains to seek out.

If Linklater could have simply flipped on the Criterion Channel, he might not have gone to the trouble of renting film prints and hosting screenings, and he might not have assembled the collaborators who helped him make Slacker. Even if he’d made it without them, he might not have learned the promotional skills—developed through AFS—that resulted in the film’s distribution. Without Slacker’s success, his second movie likely wouldn’t have been an opportunity on the scale of Dazed and Confused. Maybe he’d have been forced to leave Austin to seek his film fortune. And without AFS, there would have been no AFS Grants and no Austin Studios cementing the city’s status as a production hub (though that has waned due to the Legislature’s reluctance to grant production incentives).

Linklater, though, never just wanted to sit alone in his living room streaming the masters of cinema. “The spirit longs to be a part of a community,” he says. “It’s an important thing in people’s lives. I found satisfaction in showing a film to an appreciative audience—one hundred people, or even forty people, watching a movie and hanging out after, talking.”

Just before shelter-in-place orders went into effect, Linklater got roped at the last minute into introducing a special presentation of Brewster McCloud at the AFS Cinema, in conjunction with its Texas Film Hall of Fame induction the next night. Even after decades of doing it, Linklater still doesn’t much care for public speaking.

That’s peculiar, since his discussion of Robert Altman’s aggressively bizarre 1970 Houston-made farce was insightful and funny. He even brought a prop. He smiled broadly as he unveiled a Japanese poster for the film that featured the image of a woman’s naked torso, along with smaller images of lead actor Bud Cort and the Astrodome, where much of the film is set. Linklater owns thousands of movie posters, a selection of which adorn the lobby and restrooms of the AFS Cinema. “Look at the translation of the name of the movie,” he said, pausing to flip back the long brown hair that hung down in front of his face as he leaned over the poster. “They just go ahead and called it ‘BIRD SHT.’ ” (The alternative title makes sense if you’ve seen Brewster McCloud.)

Describing it as one of the great Houston films (“not a long list”), he argued that its absurdist approach to reckoning with the social upheaval of its era is more relevant than ever. (The screening took place months before George Floyd’s killing spurred Black Lives Matter protests across the country.)“This movie’s time is now. It’s a real comment on just how unhinged society was,” Linklater said. “Look at the cinema of the time. Like, one year later, there’s Dirty Harry. That’s a whole other right-wing reaction to just how society has come off the rails. This is Altman’s version of that.”

He recalled meeting Altman, one of his film idols, when he took Slacker to Sundance. “Dork that I was, I went up and had to say, ‘Oh, Mr. Altman, you know that scene in The Long Goodbye where Elliott Gould drops the cigarettes? That changed my life,’ ” he said. “He looked at me, goes, ‘I can’t be responsible for that.’ ”

Then the Texan auteur scampered off the stage to take his seat among the crowd. The house lights went down. The projector lights flickered on, and we entered another world—together.

This article originally appeared in the July 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Everyday Auteur.” Subscribe today.

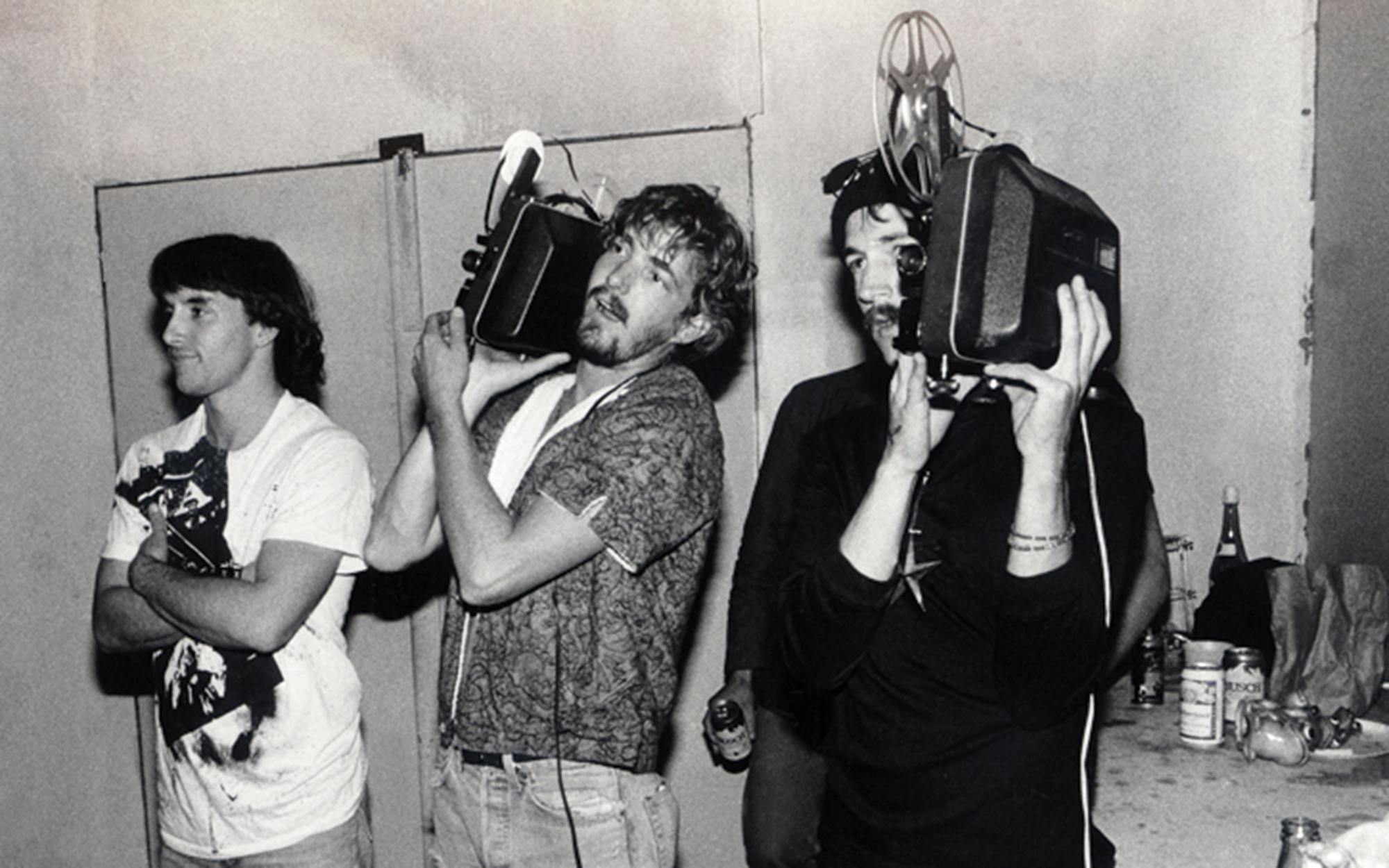

Correction 06/02: An earlier photo caption incorrectly placed Clark Walker in the photo with Richard Linklater and Lee Daniel. It has been amended to reflect that Daniel’s brother, Bill, is in the photo.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- SXSW

- Richard Linklater