When Dave Hickey shuttered his gallery, A Clean Well-Lighted Place, fifty years ago, it was the end of a brief, delightful moment in the history of Texas art. During its life span, from 1967 to sometime around 1971 (everyone is a little hazy on the details), Hickey almost single-handedly created a milieu in Austin that gained national cachet. Along with a few like-minded curators elsewhere in the state, he helped launch and shape the Texas art scene as we know it today, with its dynamic ecosystem of galleries and museums and a collecting community that will pay serious money for contemporary works. He offered up a cosmopolitan vision of what Texan aesthetics can be.

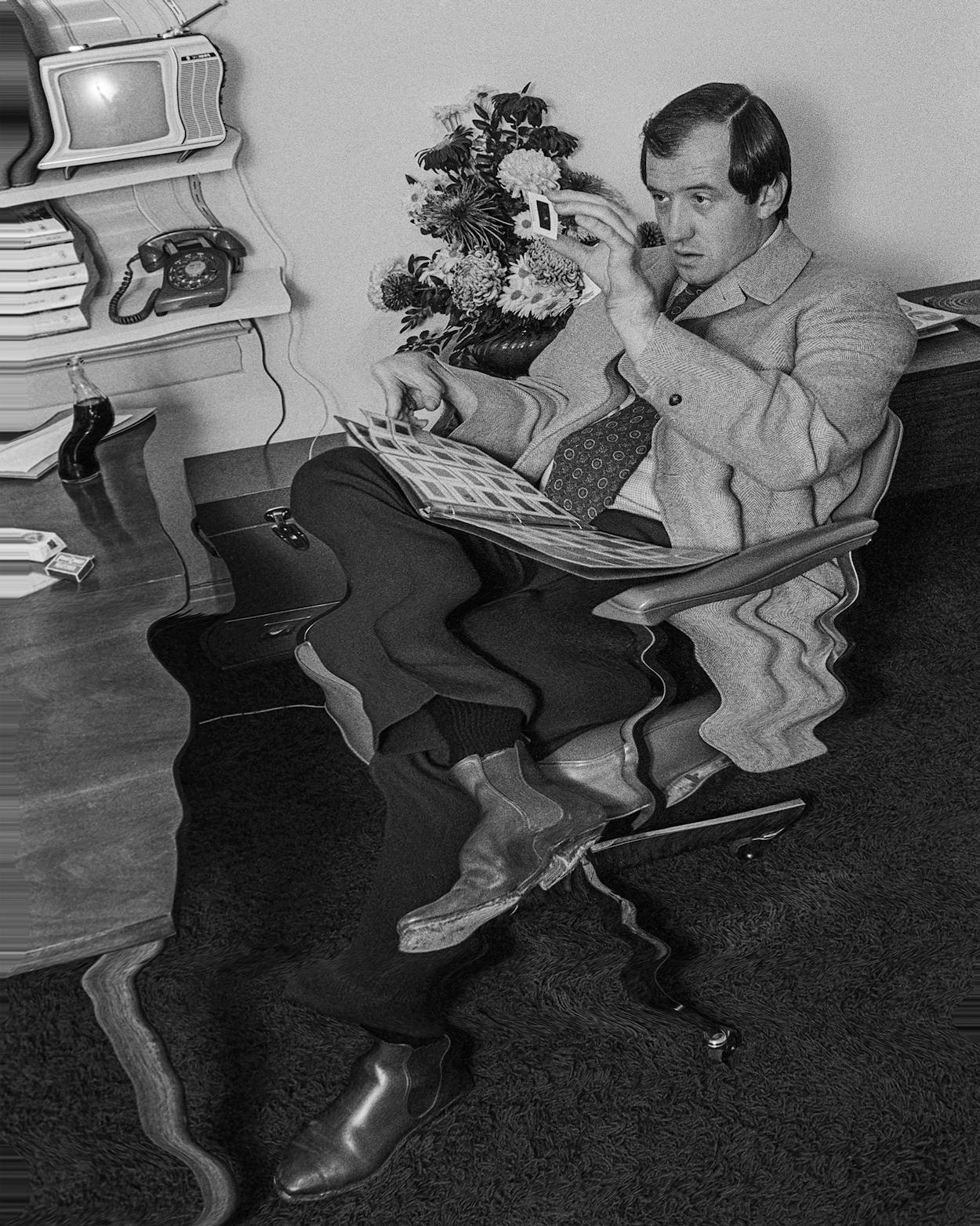

It’s an overstatement to say that Hickey, who is now 82 and living in semiretirement in Santa Fe, had all this in mind when, as a 28-year-old linguistics graduate student at the University of Texas, he opened the gallery on the first floor of the two-story rental home he shared with his then-wife, Mary Jane. But he wasn’t a naïf, and it wasn’t an accident.

Born in Fort Worth in 1938, Hickey had a rough but cerebral childhood. His father, also named Dave, was a frustrated jazz musician who worked at a series of car dealerships and parts-distribution warehouses, moving the family around the state and country as he landed and lost various jobs. His mother, Helen, was a frustrated painter who gave as good as she got in the marriage. The household was dysfunctional but interesting, filled with books, art, and music. Dave, the oldest of three kids, soaked up the cultural influences. He also escaped as often as he could, spending long days in record stores and bookshops, movie theaters and museums.

By the time he arrived at UT-Austin for graduate school, after college at Texas Christian University, Hickey had an air of sophistication. He was named editor of the campus literary magazine and then became a columnist for the Texas Observer. He played wry folk songs at parties and quoted Susan Sontag and Gilles Deleuze. People talked about him. “He had this reputation that flew around that he used to run with Larry McMurtry and those guys and that he had been as good as McMurtry, and maybe better,” says Brian Dippie, a cultural historian who was a UT graduate student in American civilization at the time. “In person he was such a serious, intense conversationalist. You always felt like he would see through you.” Max Gimblett, a painter who showed at Hickey’s gallery, remembers him as “one of the most intelligent people I’d ever known. Free of a whole lot of bullshit about art. Free of other people’s opinions.”

In the fall of 1967, almost finished with his doctoral program, Hickey decided he wanted to open an art gallery. “I got right up to the point of defending my dissertation,” he later told an interviewer, “before I realized I really couldn’t do it. So, I put on my nice glen-plaid suit, went down to the bank, and borrowed ten thousand dollars. (I was a good risk, right? About to become a PhD, hee, hee.) After about two months of generally frenetic preparation, we opened A Clean Well-Lighted Place.”

It was a leap. Decades later, Hickey would make a name for himself as an essayist and art critic. He would be tenured at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, awarded a MacArthur Foundation “genius” fellowship, and sought out for exhibit-catalog essays and lecture series. His ideas on the complex relationship among art, beauty, commerce, and democracy would exert a dense gravitational pull on the American art world. But in 1967 he had no formal credentials or business experience. What he had was a willingness to take risks, a lot of charisma, and a discerning critical eye, which had been trained informally over the previous few years, whenever he ventured to New York to attend shows and meet art-world people, among them the émigré dealer Leo Castelli, whose gallery on the Upper East Side of Manhattan was host to some of the most important artists of the postwar era.

“All of it derives from me at Leo Castelli’s,” says Hickey by phone from Santa Fe. “I loved the way things felt and looked there. It was that area over by the Met. That whole neighborhood was special—the interiors, the gray light, the beveled windows. Leo had this beautiful gray room with a bright purple giant brushstroke by Lichtenstein in it. I wanted to have that room in my house.”

It was a ripe time to launch a new arts venture in Austin. The music scene was simmering, with the Vulcan Gas Company opening its doors in the fall of 1967 and bands such as the 13th Floor Elevators and Shiva’s Headband developing a Texas strain of psychedelic rock. The university was rapidly modernizing. The campus chapter of the leftist organization Students for a Democratic Society was one of the biggest in the country, and the Texas Observer was breaking ground in alternative journalism.

The visual art scene, however, lacked a center. Local artists were creating work that could compete in New York, but Texas galleries weren’t interested in showing contemporary art, and few buyers knew what to select to impress their friends. “It was just bluebonnet paintings,” remembers the artist Barry Buxkamper, who was an undergraduate student at UT when he first met Hickey. This was the void Hickey set out to fill.

The name “A Clean Well-Lighted Place” was a reference to a rather bleak story by Ernest Hemingway, who was one of the subjects of Hickey’s dissertation, and a literal description of what he wanted to create: a gallery with good art on the walls and good natural light. It was also an inside joke about what the gallery represented to him: the controlled burn of his previous life as an academic. “I coined the first axiom of ‘combat aesthetics,’ ” he later said. “Nothing can light up the place you are like a burning bridge behind you.”

The first iteration of the gallery was at Twenty-third and Rio Grande streets. There wasn’t enough parking so close to campus, however, so the couple—Mary Jane was in charge of many of the day-to-day details—soon moved the gallery to a commercial space at Twelfth and Nueces, four blocks west of the Capitol.

“It was singular in Austin’s history of tastemaking,” says Annette Carlozzi, the author of Fifty Texas Artists and former head curator of the Blanton Museum of Art. “Dave’s selections were so acutely sensitive to the trends of the moment that were happening on both coasts as well as in Texas. They were sophisticated in a way that nothing else in Austin was, at least off campus, outside of UT’s rich intellectual environment. And Dave was such a unique figure—the largeness of his personality and the sweep of his ideas. I think Dave educated and refined the eyes of native Texans who first and foremost were drawn to his character, to who he was. That’s what brought them to the gallery, and if they could afford to buy things, then they would.”

Hickey assembled his stable of artists intuitively, he later wrote, “from among our generally disconsolate contemporaries.” Some of his artists were right out of undergraduate or graduate art programs. Others were further along in their careers. He found them wherever they were—at art shows and rock concerts and film screenings. He compared notes with the few other gallerists and curators across the state who were on the same wavelength. After a while, the artists began to find him. “It was Austin. You sort of met people,” he says.

The gallery’s first show was of paintings by Jim Franklin, a Galveston native who was doing comic illustrations for the underground Austin paper the Rag. The show didn’t sell much, but Hickey’s judgment was soon vindicated; a short time later Franklin debuted his armadillo drawings, which endure to this day as icons of countercultural Austin. Franklin also became known as one of the players in the national underground comix movement, along with other Texas artists such as Jack Jackson and Gilbert Shelton (both of whom also were featured at A Clean Well-Lighted Place).

“Dave was the best dealer you could have and the worst,” says Buxkamper, who began showing at the gallery after Hickey saw his BFA show. “He really championed your work. Got it into good exhibitions and major collections. He was the worst of dealers because of the money. He owes me money to this day. He’s not ashamed of it. It’s also why he was the best of dealers. He wasn’t selling commodities. It wasn’t a product he was marketing. It was a vision, a person. He would do whatever was necessary to gain attention for his artists. He once traded a painting of mine to a big collector in Fort Worth. In his mind, he was going to trade it, sell it, and split the money, but that didn’t happen. I was quite happy to have the recognition rather than the money.”

“I was bad at paying artists,” admits Hickey, unapologetically. “I still owe Peter Plagens. I still owe Stephen Mueller, although he’s dead. I owe Barry money. I fully intended to pay everybody, of course.”

“It was just bluebonnet paintings,” one artist remembers of the Texas scene at the time. This was the cultural void Hickey set out to fill.

The majority of the artists Hickey showed were native Texans, including the artist and musician Terry Allen, the pop painter Mel Casas, and the sculptor Luis Jiménez. Hickey also showed a decent number of recent arrivals, such as the New Zealand–born Gimblett, the California transplant Plagens, Florida native Jim Roche, and Germany’s Juergen Strunck.

It’s possible, in retrospect, to identify some common themes and practices in the artists’ work, but what most clearly tethered it together were Hickey’s eclectic taste and his openness. He was happy to show abstract artists, such as Gimblett and Plagens, who were in tune with what was happening in New York or Los Angeles. He was also keen to show virtuosic storytellers like Jiménez, crazy rednecks like Roche, and hard-to-categorize polymaths like Allen and the balloonist and inventor Vera Simons. Whatever was good and didn’t seem too derivative. Above all, he wanted to show art that he wanted to be in the presence of.

“Back in the nineteen-seventies, people always wanted to know if [running the gallery] was any fun, and I always told them, yes, it was a great deal of fun—nervous, anxious, vertiginous, heartrending fun,” he later wrote. “My favorite thing, I told them, was showing up at my little store in the morning. I’d come in through the back door, make some coffee in the office, carry it into the dark gallery, and hit the lights. The space would spring to life, and I would just stand there for a little while, looking around and sipping my coffee. Then I would go back to the office, pull over the phone and the Rolodex, and go to work. That was the best part.”

The few other gallerists in Texas who were interested in contemporary art, such as Fredericka Hunter, in Houston, and Murray Smither, in Dallas, were coconspirators rather than competitors, as were the more open-minded curators at the museums in the big cities. There was plenty of good art to go around, and they all had an interest in propping up one another.

“From a distance it almost began to look like an art community if you squinted,” Hickey later said. “The artists added to the illusion, of course, but the support systems mostly consisted of myself, Murray Smither, Janie Lee, and Fredericka Hunter, all pretending that we were selling new art to phantom collectors, while Henry Hopkins at the Fort Worth Art Center, Robert Murdoch at the Dallas Museum, and Martha Utterback at the Witte in San Antonio pretended to believe us. Mostly, we talked to one another on the phone.”

Hickey’s efforts on behalf of his artists included taking out expensive ads in Art in America and Artforum; relentless networking with gallerists, curators, and editors in Texas and New York City; and putting the kind of thought and care into the details of marketing and branding that one might have expected from a hip gallery in Manhattan. He produced delicate hand-printed invitations to exhibitions, provocative bumper stickers (“Sincerity Is for Sissies”), attention-getting posters, and lo-fi catalogs. Even his business card fit the concept: a piece of thick matte-black paper, folded over like a place setting, with the gallery’s name floating on a field of black and one edge of the card artisanally torn.

Barbara Zabel, a professor emerita of art history at Connecticut College, who was then a graduate student in Austin, says of Hickey, “He embraced artists whose materials were considered ‘tacky,’ like George Green’s objects made of green linoleum tile, or simply unorthodox, like Haydn Larson’s iron farm tools transformed into sculpture or Vera Simons’s vinyl inflatable ‘pillows.’ The presence of green linoleum occupying an art gallery or a piece of iron leaning against the wall or a triangular pillow floating around the space had the liberating effect of nudging you to see the art—and the world—differently.”

The overall message was clear: what was happening in Austin was worth taking seriously at the highest levels of high culture in America. The haute brand and the elegant physical space of the gallery legitimized the art, which could be rowdy. And Hickey himself—an urban sophisticate with legitimate Texas roots and a cracklingly fierce intellect—was a kind of advertisement for his gallery.

The effect on the Texas art circuit was palpable. The New York magazines began covering Texas art. Texas artists began showing and selling in New York as well as in Texas, in venues and to buyers who never would have looked at them before. Hickey estimates that 70 percent of his sales were to buyers outside Texas, mostly in New York. The Whitney Annual (which became the Biennial in 1973) began including more Texas artists, thanks in no small part to Hickey’s work as an informal scout for Marcia Tucker, a senior curator at the museum whom he’d befriended on his New York trips. A genuine Texas art scene coalesced. There was a tension in it, between inside and outside, Texas and New York, that gave off a tangible charge.

“We created this monster called Texas Art,” Hickey later said, “and it nearly devoured the whole scene.”

“He never gave you any warning,” says Roche. “I was living on a farm, shooting birds to eat because I didn’t have a g—damned dime. I’m working there one day, and I was pretty scruffy at the time, when they come driving up. I recognize the junk car as Dave’s . . . but then there’s a g—damned Mercedes trailing him. The person gets out and is very nice to me. She says, ‘Is it okay to see your work?’ I said, ‘Well, you can.’ She went in there, and she came out just howling. That was Marcia Tucker. That’s how I ended up in the 1970 Whitney show.”

The Roche piece that made its way to the Whitney was one of his Potted Mamas, large ceramic, semiabstract sculptures that had breasts appended to them at various places. They were “funky,” to use the word that would come to define an important strand of what was happening in Texas at the time.

“There was a kind of cowboy pop art,” says Plagens, now an art critic for the Wall Street Journal. “They had this attitude of ‘F— this shit. I’m going to drink some beer and make some art.’ It didn’t cotton to the mainstream. It wasn’t Texas specifically so much as ‘F— you, New York.’ It was similar in a lot of ways to what you were seeing in Chicago. We’re not either coast, or under the gun of Europe.”

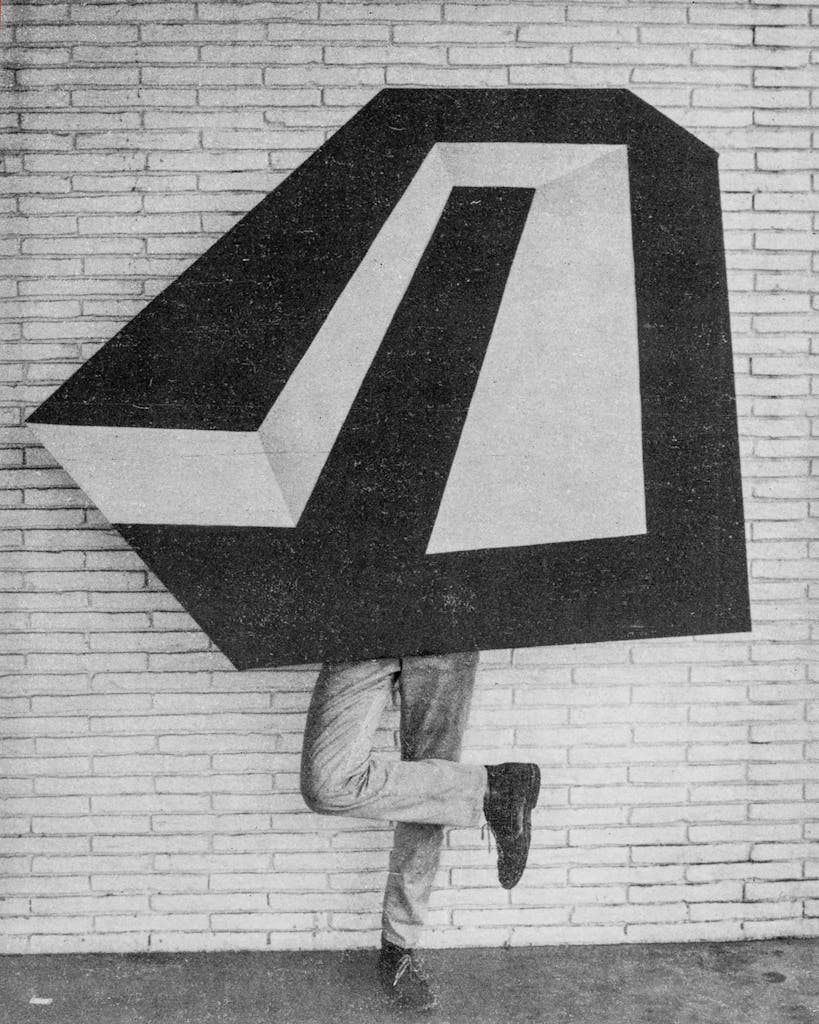

In December 1970 Hickey curated an exhibition at St. Edward’s University, in Austin, under the rubric of “South Texas Sweet Funk.” It made the argument—visually and in the catalog essay—that there was a specific breed of Texas funk art that was worthy of national attention. One of Roche’s Mamas was in it, along with Franklin’s armadillos, original drawings from Shelton’s Wonder Wart-Hog, an oversized striped weenie from Bob “Daddy-O” Wade, a cow by Buxkamper, and work by the El Paso–born Casas that was influenced by Mexican murals and circus posters.

“Whatever indigenous culture Texas has is being created by artists, writers, and musicians who have channeled their energies into making an artistic community in spite of the existing cultural institutions,” Hickey wrote around this time. “Not a counterculture (the society is too eclectic and atomic to counter), simply an other culture which sustains itself by guile and cunning, and, if not by capitalism, at least by very free enterprise . . . Weird—but in the great Texas tradition of weird enterprises.”

The show wasn’t particularly well attended, but it was covered in Artforum, and it set down a conceptual marker that would make it much easier for Texas artists to brand themselves—and be branded as—Texas artists. It was a development that Hickey came to rather regret, not because he disliked Texas funk but because its marketing success had the effect of crowding out other ways of being, and being seen as, Texan.

“We created this monster called Texas Art, ” Hickey later said, “and it nearly devoured the whole scene. We had begun by trying to convince people that there was something special happening in the visual arts down here, and reaching for the metaphor at hand, we invoked the mythos of Texas. You know, ‘Howdy, ma’am, I’m loose as a goose, as big as all outdoors, would you like to sashay over to the Red Dog saloon with me?’ Talk about waking the sleeping tiger! Before you could say ‘Look out!’ the art was touted as special because it was being done in Texas, because it was about Texas. Which was absolute bullshit. It was special because it was good art, and all the more admirable because it has been made in a cultural desert.”

Carlozzi, the former Blanton curator, believes Texas art ultimately benefited from the tension among all these highly charged narratives and imperatives. “Of all the regionalisms of that era, Texas just had, in my opinion, a higher level of quality,” she says. “There were fascinating stories to tell and materials to use and histories to tap into and places to do things. It made for this really rich ecosystem out of which to generate art.”

The St. Edward’s show turned out to be a last Texas hurrah for Hickey. Within a few months he was tapped to run the Reese Palley Gallery, in the SoHo area of Manhattan, and he and Mary Jane relocated to New York. The Texas art scene kept growing in his absence, particularly in Houston, but without Hickey, Austin ceased to be viewed as an epicenter. It would be another thirty years or so, says Carlozzi, until the energies of the visual art scene in Austin began gaining widespread national attention again. “The flame burned brightly,” she says, “then he left and took it with him.”

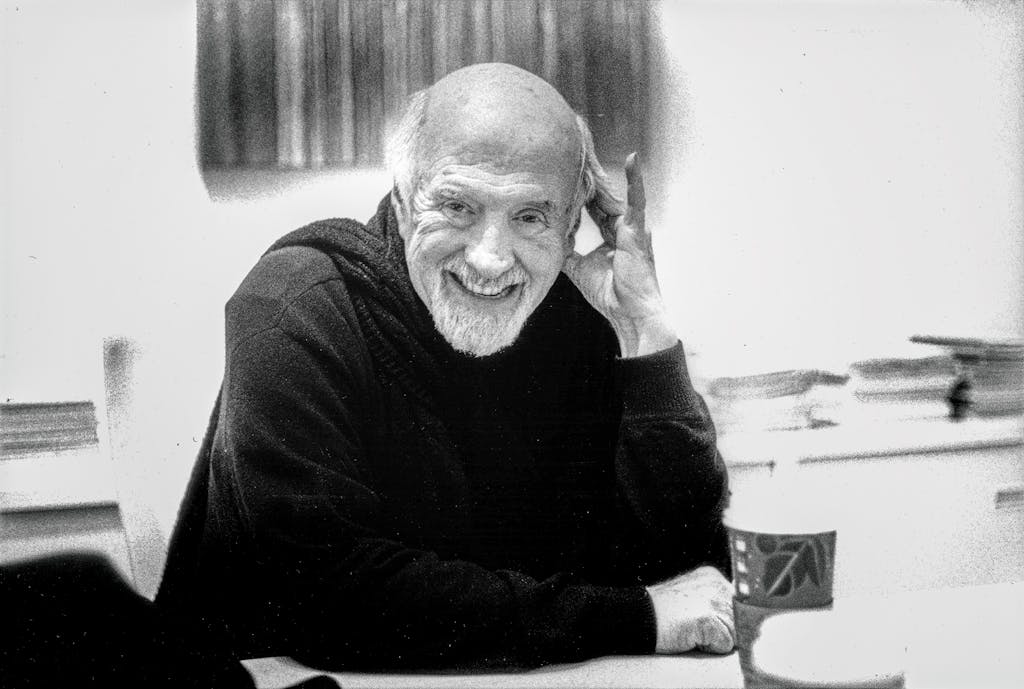

Hickey, for his part, didn’t entirely flourish outside Austin. In New York he quickly got sacked from Reese Palley after he refused the gallery owner’s demand that he put on a show of Yoko Ono’s art. “We had a level of cool that didn’t admit Yoko, or even the Beatles,” Hickey says. He had a brief run as an editor for Art in America (and a longer run as a writer) before burning that bridge behind him too. For most of the seventies he ditched art entirely, instead writing about music for publications such as the Village Voice and Creem and Penthouse. After a few drug-fueled years in Nashville, writing about outlaw singers for Country Music, he retreated to his mother’s house in Fort Worth to recuperate from a bad case of pneumonia. He ended up spending most of the next decade there, sometimes writing about art for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and for museums but mostly doing drugs and working on pop songs, a few of which were recorded.

It wasn’t until the late eighties, after landing a job as a professor at UNLV, that he began producing the kind of stylish, erudite, and down-to-earth essays that would make his name as a writer. It’s easy to see, in the body of work he’s produced since, the imprint of his time running A Clean Well-Lighted Place. As a writer he remains in many ways a small-time art dealer—hunting for beauty, hustling to generate community and attention around it, making money when he can but never with great conviction or efficiency. Clearly visible too in his writing is the ghost of Texas. It’s the source of his pain, the landscape of his dreams, and the mythology from which, like so many Texans before and after him, he’s spent his life trying to escape.

“But home, in the twentieth century, is less where your heart is than where you understand the sons-of-bitches,” he once wrote. “Especially in Texas, where it is the vitality of the sons-of-bitches which makes everything possible, where there is more voracious mercantile energy, more vanity, and more pretentiousness than any place I’ve been.”

The gallery’s influence on the state, and on Texas art, has been both pragmatic and symbolic. Hickey elevated and discovered artists who, for good and ill, went on to distinguish Texas art as a thing. He helped direct the eye of New York to Texas and helped cultivate a taste for contemporary art in local buyers. He’s one of the impresarios of the funkiness that Austin now seems determined to shed. And though he’s not the most important figure in the history of Texas contemporary art, he is one of its most romantic. The legend of A Clean Well-Lighted Place lives on, all the more potent for the brevity of its actual existence. It was sophisticated and profane. It was “F— you, New York,” but also “Notice us, New York.” It was just the right amount of cowboy and redneck, an electric current from the border, and, above all, a reminder to Texans that their state isn’t necessarily what they think it is.

“It is a cosmopolitan place,” Hickey says, “although Texans like to pretend that they’re all down at Luckenbach.”

Austin writer Daniel Oppenheimer is the author of Exit Right: The People Who Left the Left and Reshaped the American Century and Far From Respectable: Dave Hickey and His Art, which will be published by the University of Texas Press this month.

This article originally appeared in the June 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Goodbye, Bluebonnets: Hello, Green Linoleum.” Subscribe today.