I want to take a minute of your time to discuss golf. Specifically, a golf course. My golf course: Lions Municipal, in Austin. Maybe you’ve heard of it and, perhaps, if you’re a golfer, have even had the pleasure of teeing it up there. It’s a beautiful place and I love it. But unfortunately, Muny, as it is known, currently finds itself in a precarious situation.

The course is operated by the City of Austin but sits on a 141-acre parcel owned by the University of Texas, which has leased the land to the city since 1936 and to the Austin Lions Club for a dozen years prior to that. Simplified, the problem for Austin’s first public golf course, which was built by the Lions in 1924 near the banks of what is now Lady Bird Lake, is this: Muny’s future, after nearly one hundred years of existence, is uncertain. Its lease is set to expire in a couple of years and the university, up until recently, had intended to not extend it. Instead, it had planned to make the prime Central Austin land available for development. No more Muny.

Texas breeds great golfers. Theories as to exactly why range from the state’s abundant wide-open spaces, which have allowed the game to flourish, to a mostly pleasant climate that is favorable to year-round golf. And then there is the belief that it has to do with a yet-to-be-identified element found in the water.

But whether it is plentiful courses, plentiful good weather, an intestinal fortitude of the kind that junior high football coaches are always yelling about, or a combination thereof, the fact is Texas has produced an inordinate share of the game’s most recognized names. Indeed, the annals of golf brim with the likes of such Texans as Ralph Guldahl, Babe Didrikson Zaharias, Jimmy Demaret, Byron Nelson, Ben Hogan, Kathy Whitworth, Lee Trevino, Lee Elder, Sandra Haynie, Tom Kite, Ben Crenshaw, and of late, a young man named Jordan Spieth.

To illustrate the point extra clearly, take this month’s Masters Tournament, the pinnacle of American golf, played at Georgia’s storied Augusta National Golf Club since 1934. Nine of the first twenty tournaments were won by a Texan; Texans have produced the most Masters wins (thirteen) of any state (California has ten); two of Augusta National’s three named pedestrian bridges are dedicated to Texans (Hogan and Nelson); and the annual champions dinner that kicks off the tournament has been hosted by a Texan since the tradition began, with Hogan, in 1952. (The reigning champ gets to choose the menu, and last year’s dinner featured barbecue, compliments of 2015 winner Spieth.)

This brings me back to Muny. While the course’s future may be unclear, its colorful past is not. Ben Hogan and Byron Nelson both played Muny in their heydays; the tough par-4 sixteenth hole is known to this day as “Hogan’s Hole.” And Haynie won the Women’s City Championship there in 1957, when she was thirteen years old, and then in ’58, ’59, and ’60, too, before finding success on the LPGA tour and a spot in the World Golf Hall of Fame.

Perhaps most important, though, is the story of the two young black golfers who set in motion a chain of events that may well prove to be the course’s saving grace. It was 1950, when there was not a single desegregated public golf course anywhere south of the Mason-Dixon Line, and these two adolescent golfers, who were also caddies at Muny, started playing a round of golf before anyone could prevent them. When they were discovered out on the course, mid-round, a call was made to the mayor’s office and it was decided then and there to let them play on. Muny, on that day, became the first golf course in the South to desegregate—three years before Brown v. Board of Education. For this reason, Muny was recently added to the National Register of Historic Places and also, because of the current dilemma, named one of the country’s “most endangered historic places” by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

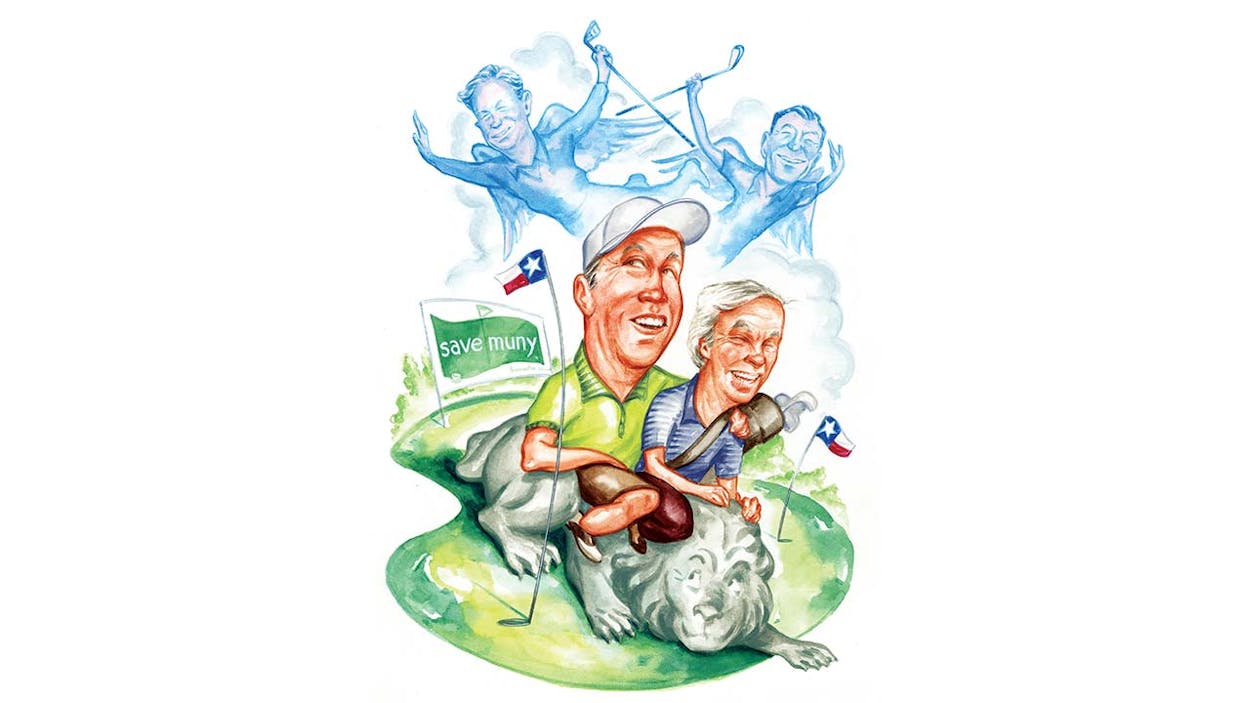

The big-name golfer most closely associated with the course, Ben Crenshaw, was born in Austin less than two years after that pivotal round. Gentle Ben, as he is aptly known, grew up just blocks from the golf course and has never in his 65 years lived more than a short drive away. I called Crenshaw recently to see if he would meet me at Muny, and he graciously accepted my invitation.

As we made our way around the course on a balmy afternoon in late February, he regaled me with great stories. Ben learned to play the game at Muny, and his promise was evident early: he shot a 74 as a ten-year-old. It was around this time that he made his first hole-in-one, on the old par-3 fifth (the course layout has been altered over the years). And although that momentous swing occurred more than fifty years ago, he remembered it vividly. He had hit his mom’s Patty Berg five-iron. His second ace came two days later on the old eleventh hole. In 1967 he won the Men’s City Championship, the youngest to ever do so, and he continued to play Muny as a member of the Austin High and UT golf teams. He then went on to a successful pro career that included two Masters championships and a place in the World Golf Hall of Fame.

Gentle Ben has played all over the world, but at Muny that afternoon, his face was aglow. We talked about friendly wagers with friends, and Crenshaw chuckled as he recalled putting contests. “The concession sold the little individual pecan pies, and we’d putt for pies.” And we talked about the two young caddies and the repercussions of their historic round.

We also talked about Muny’s future and a dream he has for the course. Crenshaw, who has had a hand in redesigning some of the world’s most renowned courses, has proposed a makeover for Muny that would restore the course to its original layout and include a new clubhouse and larger practice area. He envisions a course on par (sorry) with other historic municipal courses, like Brackenridge Park Golf Course, in San Antonio, the first public eighteen-hole course to be built in Texas; Houston’s Memorial Park Golf Course; and the Tenison Park Golf Courses, in Dallas—if not a world-class public course like Bethpage State Park, in New York, or Torrey Pines, in California. And he’s offered his services—a million-dollar value—for free.

Like Crenshaw, I learned to play golf at Muny (I wish I could say I learned to play golf like Crenshaw at Muny). I’ve never made a hole in one, but I did once eagle the treacherous par-5 twelfth hole, and I broke 80 there for the first time. Thus far, I’ve spent 25 years with buddies traipsing its beautiful grounds, and I’m hopeful, like so many others, that Muny will be here forever.

At the beginning of the year, the university softened its stance, expressing an interest in negotiating a new agreement with the city, and at the Capitol, a bill has been floated that would transfer control of the land from the university to Texas Parks and Wildlife, better securing the course’s future. To those who care about Muny, this all sounds sort of familiar. The Save Muny campaign was first fired up in 1973 by a group of concerned citizens and had to regroup in the late eighties and again more recently to deal with the same perilous situation. Whether one of the proposed options is better than the other, I can’t say, but I do know that losing Muny would be a shame of historic proportions. This is the place, after all, where the great Ben Crenshaw once examined my putting, quirks and all, and deemed it to be A-OK.