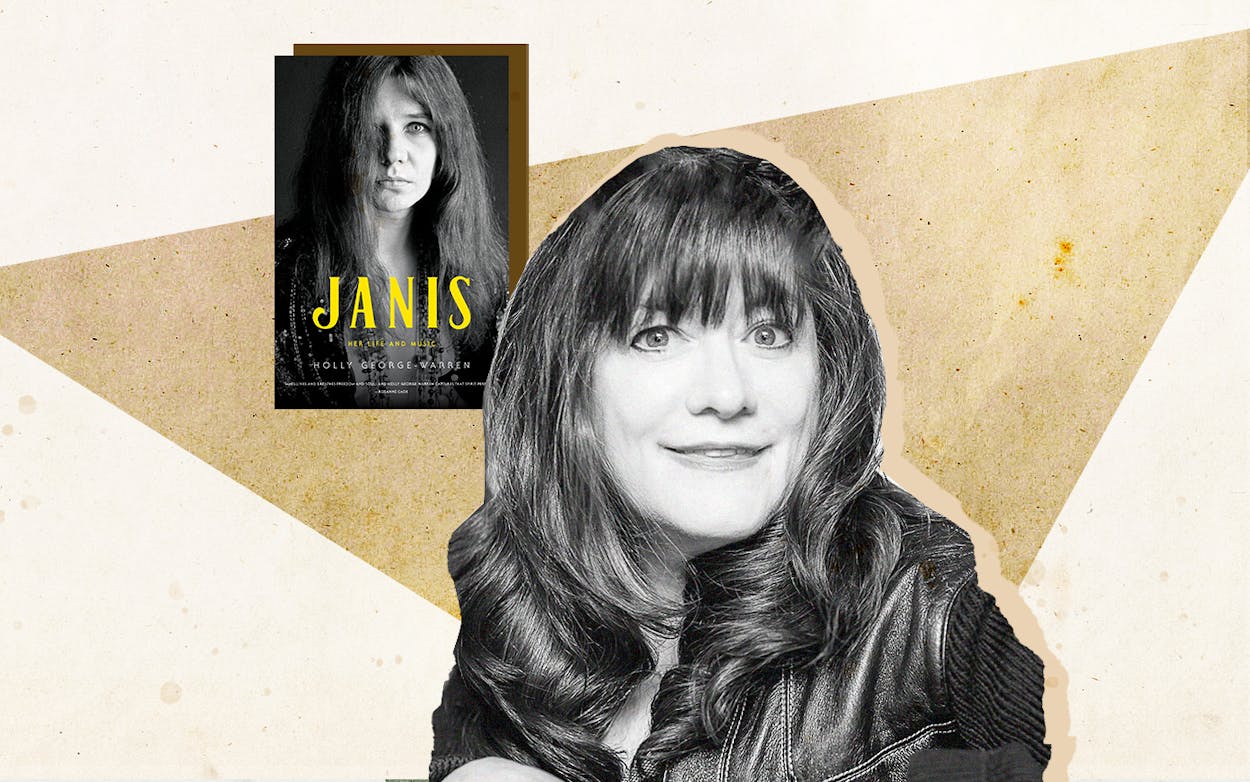

Holly George-Warren’s Janis: Her Life and Music (Simon & Schuster, October 22) tells the story of rock and blues singer Janis Joplin, who grew up a rebellious teen in Port Arthur, moved to Austin and began singing folk music, had a break-out performance in 1967 at the Monterey pop festival, sang at Woodstock in 1969, and died of a heroin overdose a year later at the age of 27. In a wide-ranging phone conversation, George-Warren, a two-time Grammy nominee and the author of sixteen books, talked about the aspects of Joplin’s life that interested her most deeply: the singer’s early years, the sources of her musical talent, and the stress and turbulence that ultimately led to her death.

Tough Times Growing Up in Port Arthur

“Janis inherited her mother’s beautiful voice and was a natural talent. She had a traditional, pretty soprano, and she could sing exactly on key and hit all the right notes. She probably thought everybody could do this. She sang in the church choir, she sang in glee club.

“She was very close to her family when she was very young, even more so because she had been an only child until she was six and was used to getting all of this attention. But then her parents, Dorothy and Seth, decided to have more children, and she became just one of three kids.

“As time went on, she wasn’t living up to some of her mom’s expectations. She wasn’t the pretty cheerleader type girl. She was a tomboy and a rebel and did a lot of acting out, partly because of her conflicts and fighting with Dorothy, also because she was not popular at school and was frequently made fun of and ostracized.

“In many ways, she was closer to her dad. She looked up to him and thought he was an intellectual; he read books, he listened to Bach and Beethoven, he would talk to Janis about ideas. [But there was a deeply depressed side to Seth.] He felt that life was what he called the “Great Saturday Night Swindle”: people believing if they work hard all week, they’ll get to have fun on the weekend, but it never really materializes.

“The negativity rubbed off on Janis. She started running with the rebels and would-be high school bohemians, and generally feeling like a loser.

Music Became a Way Out of Her Troubles

“But then she discovered records by [blues singer] Bessie Smith and [folk and blues artist] Lead Belly [Huddie Ledbetter]. Being introduced to this very emotional, raw style of music was a revelation; it really spoke to her, and I think it set her on a quest. She started to realize that she didn’t have to sound like a little white Texas girl singing in the choir. She realized she could express all this tamped-down feeling that had been building up inside her. She could be different, she could be unique, special. That voice [she was cultivating] was a way to get attention and she relished it. And connecting with an audience—that was always the biggest part of it. But there was a flip side to the connection and the high it brought.

“When you do a concert and you connect with all these people, when you tap into a kind of collective unconscious, you have this peak experience. It just takes you to another plane. Your adrenaline is pumping, your heart is beating. And then, the concert’s over. So then what? It’s almost like postpartum depression, night after night. Coupled with that, she did have a degree of shyness and a fear of getting up on stage. I also think that a lot of musicians use [drugs and booze] as a crutch, a way to knock down their inhibitions. And Janis wanted to have no inhibitions on stage.

“So, nothing like a couple of shots of Southern Comfort to take the edge off. I think she was definitely an alcoholic, but over the years she used a pretty full spectrum of drugs. She actually tried to keep the drinking in check because liquor is much worse on your voice than heroin. There was also meth—that was her first serious drug. She got horribly addicted to it. At one point her weight was down to eighty-seven pounds; her friends in San Francisco put her on a bus back home to Port Arthur. She got clean, but eventually she tried heroin [and that was her downfall]. One of her boyfriends said that she was so sensitive and her [psychic] pain was so great that she kept relapsing, because heroin was like this big blanket that just numbs you out.

When She Was Sober, She Was in Control of Her Craft

“Over her short life, Janis perfected an image of being this blues mamma, this wild woman who just lets the emotions roll over her, who sings what she feels, but I realized there is this other part of her that people don’t know. Behind the scenes she was a hardworking musician who spent years honing her craft.

“So I began to think of it as a secret side of Janis, and it intrigued me. I felt like there needed to be more attention paid to her music, her early musical influences growing up in Port Arthur, what she heard on the radio, what records she listened to, and then, of course, the whole Austin thing, when she really started to become a musician, in her early twenties.

“One thing was key to my whole attitude about her. Back in 2012, Sony did a compilation album called The Pearl Sessions, and I was asked to write the liner notes. As part of my research, I was allowed to hear recordings that they got out of the vault, when she was finishing Pearl with producer Paul Rothchild. [Pearl was her fourth and last album, released posthumously.]

“On the tapes, it’s Janis who is totally taking the lead. You hear them talking through ideas for the songs and arrangements. Rothchild was [a huge name in the music business and famous for being] a real taskmaster in the studio, making musicians redo vocals eighteen times or whatever, very authoritarian.

“But on these tapes, Janis is in charge. She’s coming up with guitar parts, she’s coming up with tempo ideas, she’s coming up with arrangement ideas. And I could hear him, totally loving it, loving her ideas and really into it. I mean, she’s clearly running the show. Human relationships may be messy, but the music never lets you down.

“October 4 was the forty-ninth anniversary of her passing. I felt really sad all day, because I worked on the book for four years and feel like Janis is a member of my family now.”

Texas Monthly executive editor Patricia Sharpe interviewed Janis Joplin for UT-Austin’s Summer Texan newspaper in 1962. The profile is believed to be the first article ever written about Joplin’s musical career.

- More About:

- Music

- Books

- Janis Joplin

- Port Arthur