For me and millions of other Selena fans born after the Tejana superstar’s death in 1995, the 1997 biopic starring Jennifer Lopez was our first introduction to Selena and her music. I watched it religiously every year on her birthday, April 16, and whenever it happened to be on TV. I grew up with the movie, seeing pieces of myself reflected in the precocious, preteen Selena, then later in the stubborn late-teens and independent early-twenties Selena. But her story stopped—a white rose falling to the ground, as it’s shown in the movie—and mine kept going.

The story of Selena, much like that of the star it depicts, is bittersweet. In the shadow of the singer’s death, her family was struggling to heal. Selena had a massive fan base, and the sudden shock of her death created the perfect environment for opportunists to appropriate her story in pursuit of TV specials, books, and potential film projects. As Abraham Quintanilla detailed in his book years later, the spectacle surrounding his daughter’s killing and the subsequent trial of her murderer fostered rumors and speculation about both Selena and the Quintanilla family.

It was remarkably soon, but Abraham wanted to nip the gossip in the bud by putting out a definitive biopic, authorized by the family. Producer Moctesuma Esparza, whose daughter encouraged him to get involved, contacted Abraham to get the ball rolling, and brought on Gregory Nava to write and direct.

Initially, Nava wasn’t entirely sure he’d sign onto the project. “There were [other] producers who saw this as a very sensational story—a woman slain by the president of her fan club,” Nava says. “I wasn’t interested in that.”

But during a walk in Los Angeles’s Venice Beach, a chance encounter with two young Selena fans changed his mind. “I asked them why they loved Selena and they said, ‘Because she looks like us,’” he recalls. “That struck me deep in my heart. I realized the young girls in our community had no princesses, no role models on the screen. I wanted to make a film that would give these young women their princess and try to do something positive with this horrible tragedy.”

It was September of 1995, just six months after Selena’s death, and the family wanted a film out by the second anniversary in 1997. Nava got to work writing the script, sitting down for in-depth interviews with the Quintanillas and Selena’s husband, Chris Pérez. Nava pored over concert footage and home movies, and even toured with her band, Los Dinos, to get a better idea of what life on the bus was like. “The events I was depicting were all very recent,” Nava says. “Other biopics, you’re so far removed that people’s memories change, they forget things, but when I was interviewing people for this, it had just happened. I think that’s one of the reasons the film is so unlike any other biopic.”

Though he was initially a bit reluctant to participate, Pérez says he doesn’t have any regrets about sharing his stories with Nava. “I didn’t know what kind of movie they were trying to make at first,” he says. “I was running from those things at the time. I didn’t want to relive it, so I figured I’d tell my truth to Gregory and then whatever happened happened.” One story in particular—his and Selena’s elopement—has continued to stick with fans over the years. In the movie scene, Selena bursts into Pérez’s hotel room, tired of keeping their relationship a secret from her father. In tears, she yells, “He will never accept us . . . the only way he will know that I am not going to give you up is if we go out and get married right now.” At the time, Pérez didn’t know the elopement would be such a central part of Selena’s story and legacy. “I’m glad that I said it because [Nava] pretty much did it exactly how I remembered it.”

But it wasn’t until Abraham was going over the script that Nava realized Selena’s father had no idea that’s how the events had unfolded. At the time, he believed it was Pérez who had asked Selena to elope. “He didn’t want it in the movie [at first],” says Nava. “He saw Selena as a role model and didn’t want to send the message that it was okay to defy your parents. I said, ‘There’s another kind of role model—the kind who shows what it is to become your own person. A strong woman who finds her own independence.’ He agreed. We went through all of this, and I’ll never forget, he said, ‘If I have to look bad in order to make Selena look good, I’ll do it.’”

With the first draft of the script finished in early March 1996, the filmmakers immediately pivoted to casting. While the time crunch added pressure, enthusiasm for the film was palpable. In San Antonio, Miami, Chicago, New York, and L.A., more than 20,000 women and young girls auditioned for the title role, making it the second-largest casting search since the one for Scarlett O’Hara for 1939’s Gone With the Wind.

Constance Marie, who had just wrapped on Nava’s previous film, Mi Familia, came in to audition for Selena before eventually being offered the part of her mother, Marcella. “I had never heard of Selena before I did this movie,” she says. “I was a blank slate.”

The auditions were intense. Marie and a whittled down list of finalists were given video interviews and concert footage to study. During screen tests, they were put in full makeup and wardrobe and asked to perform “Como La Flor” and “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom.” By the end of the demanding week-long process, Jennifer Lopez, who had also worked with Nava and Marie on Mi Familia, had clinched the lead role. Lopez wasn’t Abraham’s first choice, but in an interview with Warner Bros. for The Making of Selena, he reveals that it was her reading of the elopement scene that won him over. “In three takes, she had it,” he said.

During filming in South Texas, the actors each found ways to connect to their real-life counterparts. In dinners with the Quintanillas, they bonded with family members and grounded themselves in their stories. Marie remembers that Selena’s mother didn’t want to meet with her. “We shot this almost a year after [Selena] passed away,” Marie says. “It was still very raw and it took time to reassure Marcella. Once she was there, I would watch her mannerisms and the particular way she moves her hands, but the hardest part was that she would be telling these stories and remember in the middle of talking that her daughter was dead. She was just heroic in her ability to get through that and contribute.”

With the weight of Selena’s death hanging over everyone, most of the family avoided the set. Only Abraham remained, day in and day out, sometimes overcome with emotion as he watched his daughter’s story being re-created in front of him. “This is the hardest film I’ve ever made,” says Edward James Olmos, who played Abraham. “It wasn’t that nobody wanted to do it, it was that it had to be done.”

“I remember at the end of our first table read, [Lopez] quietly sang ‘Dreaming of You’ over [Nava] reading the stage directions of the fans mourning and the candlelit vigil, and we were all sobbing,” Marie recalls. “So it was very emotional from the very beginning. The more you got to know the people you were playing, it became even heavier.”

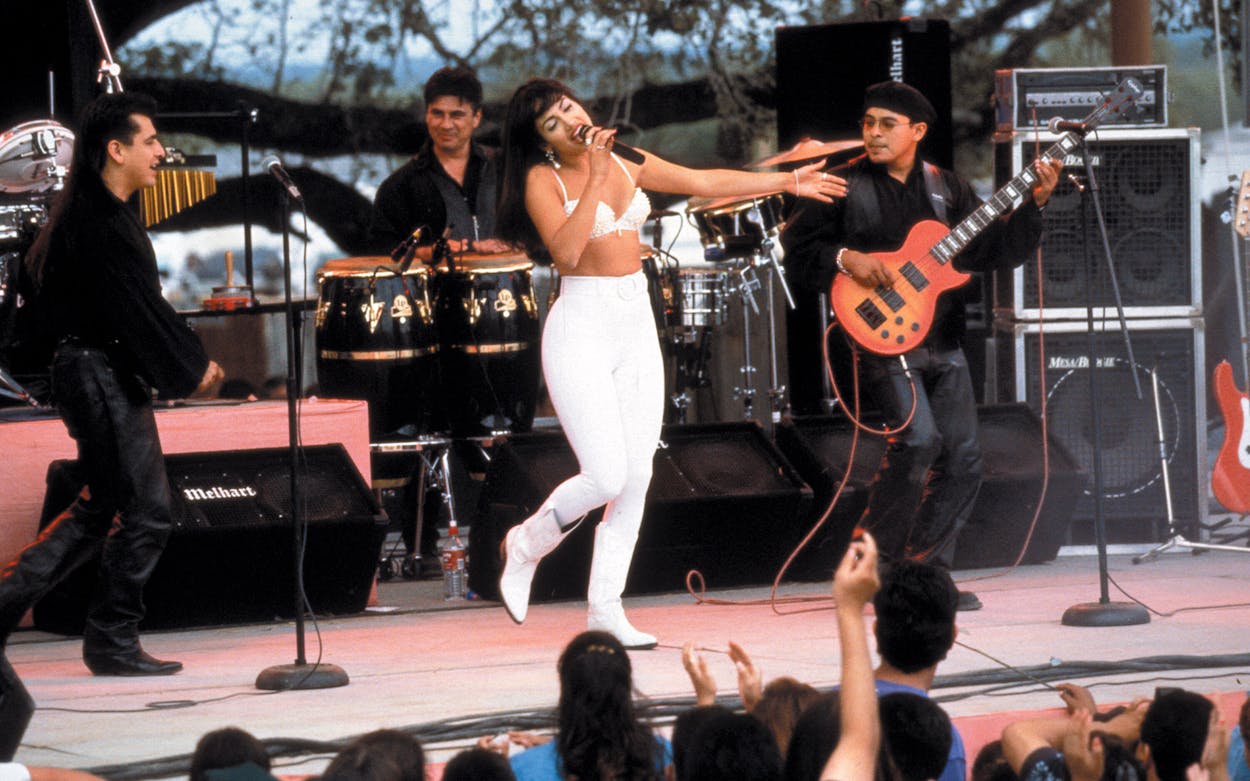

Still, the cast found moments when they were able to celebrate. When it came time to film Selena’s iconic Houston Astrodome performance at the San Antonio Alamodome, the crew put out a call in the San Antonio Express-News asking fans to come down and dress as if they were headed to a Selena concert. “We didn’t know if anybody would show up,” Nava says. “Thirty-five thousand people came. For free.”

The scene took all day to shoot, with Lopez going over the performance again and again, allowing the cameras to capture every angle. “The audience went out of their minds, cheering and weeping,” Nava says. “When it was over Jennifer and I were alone and I remember she told me, ‘I want that.’ This was her first time performing in front of a crowd. The next day, she contacted her manager to start the process of going into music.”

Then came the day everyone was dreading: Selena’s death scene. From the beginning, Nava says he never wanted to spill Selena’s blood on screen—he couldn’t do that to all of the young girls who looked up to her. Inspired by the traditions of magical realism and Greek tragedies, he chose to depict her death in a dreamlike sequence, with a single white rose falling to the stage as we hear Selena sing “Dreaming of You.”

“We really tried to focus on the celebration of her life,” Marie says. “That carried us for a long time, but when we got to the point of having to shoot the scene in the hospital, that was the heaviest day. There was talk about whether we’d need the scene, maybe even not doing it. None of us wanted to stay in that part of the movie.” They filmed it in one take.

That closeness to the story, the recency of Selena’s death, is part of the reason Nava believes the film has held up for 25 years. While many biopics are released years or even decades after the subject’s death, Selena was created when memories and emotions were still fresh. The making of the film—from Nava’s script, to the actors’ performances, and even the extras’ participation—was imbued with love for Selena and the pain of losing her. And you feel it throughout the movie, even a quarter-century later. Every time the filmmakers needed fans to show up—for the Astrodome scene, the Monterey concert, and Selena’s vigil—thousands did.

“The love and support that the Tejano community gave this film—I don’t think there’s any other film that’s ever gotten that kind of support,” he says. “That’s one of the reasons that the movie is as special as it is. Without them, it would not have been the film that it was.”

About halfway through Selena, there’s a moment when Abraham tries to teach his children a lesson, distilling more than a century of cultural struggles into a few sentences: “Being Mexican American is tough. We’ve gotta be twice as perfect as anybody else . . . We gotta be more Mexican than the Mexicans and more American than the Americans, both at the same time. It’s exhausting!”

For the past 25 years, Olmos has had this line quoted at him, and even quoted it himself when the situation called for it because it has remained painfully relevant.

Selena launched Jennifer Lopez’s career, grossed $35.5 million in the U.S., and was a mainstay of cable TV for years. The film continues to draw hundreds of fans at Selena-themed brunches and birthday screenings, and it will even get a nationwide rerelease starting April 7. It’s become a classic, an undeniable staple of Mexican American cinema. And, citing the persistent underrepresentation of Latinos in film, San Antonio congressman Joaquin Castro nominated Selena to be inducted into the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress, arguing that its success proved “once and for all that Latino stories are American stories.” In December 2021, it became one of the year’s 25 inductees.

“This film has taken on a life of its own,” Nava says. “It’s been amazing. And finally, mainstream America is recognizing that Mexican Americans, Latinos are culturally significant to this country. We deserve our seat at the table, and it’s Selena who’s taking us there.”