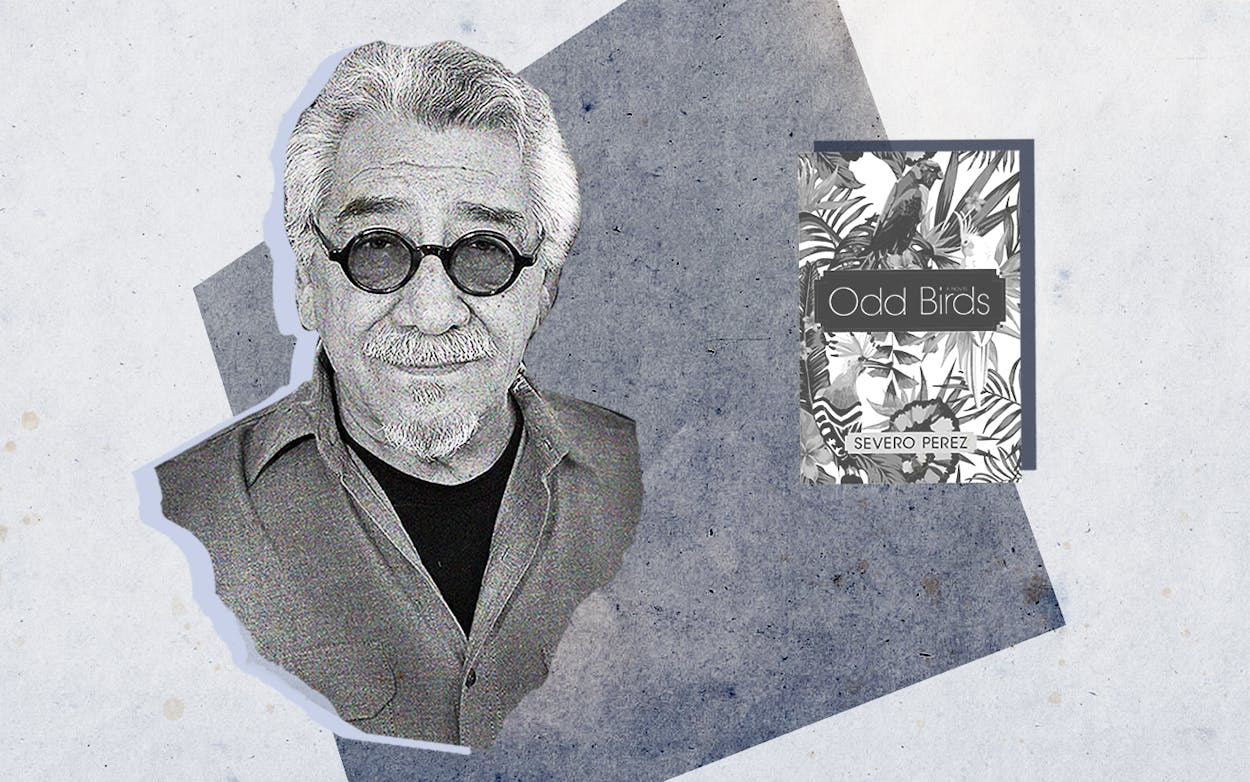

The story at the heart of filmmaker Severo Perez’s second novel, Odd Birds (Texas Christian University Press), is a pitch-perfect picaresque tale whose origins date to 1971, when he left his native San Antonio to seek his destiny in Hollywood. Perez has been in Los Angeles ever since, where he has directed and produced such films as 1994’s …and the earth did not swallow him, a classic of Chicano cinema based on Tomás Rivera’s 1971 novel, and documentaries exploring the work of the artist Carmen Lomas Garza and the dancer-choreographer Rudy Perez.

But even though Severo Perez created an entirely new life for himself on the West Coast, the complexities of Bejareño reality have continued to fascinate and inspire him.

“Odd Birds is a valentine to a San Antonio that no longer exists,” Perez said in a recent interview, though this particular valentine is simultaneously wry, poignant, and inflected with an unstinting, if humble, advocacy for the struggle against the scourges of prejudice and privilege. The San Antonio of 1961 that Odd Birds conjures is a place of auspicious, unexpected meetings, where artistic daring can transform a mundane life, where momentous social change is underway, where the fortunes of the downtrodden can be reversed in one fateful day.

Pretty much the San Antonio we all know and love today.

At the outset of Odd Birds, the book’s main protagonist, seventy-year-old Cuban-born artist Cosimo Infante Cano, finds himself almost penniless on the streets of San Antonio after a series of Quixotesque misfortunes. Cano, a longtime participant in Paris’s thriving modernist and surrealist artistic communities, followed his Texas-born lover from France back to her hometown, the “cultural backwater” of San Antonio, only to arrive and find she has disappeared, along with $45,000 he had transferred to her bank. Broke and homeless, he is regarded by some as a vagrant, by others as a suspicious Cubano who may be an agent of Fidel Castro’s communist regime.

For the rest of the novel, Cano wrestles with a few central questions, all of which are answered in good time: Has he been the victim of a big grift? Has his lover died? What’s happened to his precious savings? How will he survive this ordeal and return to his Parisian home?

In the course of following Cosimo’s strenuous efforts to put his life back together, we are introduced to a host of “odd birds,” San Antonio eccentrics and outliers who are themselves variously involved in desegregating the city library, battling homophobic violence, and prodigally puffing weed as if it were 1969 rather than 1961.

The book veers from its start as a noir-ish tale to an increasingly panoramic historical novel that echoes O. Henry’s and Sandra Cisneros’s rich versions of San Antonio’s characters and haunts. From its Parisian flashbacks to its San Antonio set pieces, Odd Birds presents an uncannily interconnected world. It’s the only novel I know of that name checks French surrealist novelist/theoretician Georges Bataille and legendary Mexican American jurist Carlos Cadena.

But what’s most striking is how vividly the book captures a city that has been at the center of far too few works of art. (Though Amazon’s recent animated series, Undone, also set in the River City, goes some way toward addressing that lacuna.) The San Antonio of yore seems indelible in Perez’s imagination, from scenes set in the grand halls of the old Post Office “tiled in beige marble with Italianate chandeliers” to frequent references to such institutions as the Mexican Manhattan Restaurant, Joske’s department store, Sommer’s Drug Store, and Schilo’s Delicatessen.

Perez is actually a bit cheeky about how true the novel is to the city of his youth. “Most of this book is a product of my imagination,” he writes in his acknowledgements. “I chose San Antonio as the setting because, half a century ago, I knew the city well. The story could have taken place in any city where there is a river walk, five military bases, and a war memorial in the center of town.”

“When I was six years old I was going to the movies by myself,” Perez says, explaining his vivid sense of the city that once was. “I was going to the Majestic Theatre by myself. I explored downtown San Antonio by myself. I was a little tyke, I was very verbal, so people accepted that this tiny tyke knew his way around the city, could take a bus everywhere he wanted to go, and so I had a wonderful relationship with San Antonio, and I loved the downtown, the stores and the shops and the windows.”

Even at that age, Perez says, he was a loner who learned to love movies at the storied Majestic, Aztec, and Texas theaters. His memories of these childhood urban walkabouts give Cano’s solitary downtown wanderings a distinct sense of reality. (In fact, Cano is inspired by a real-life Cuban refugee whom Perez remembers wandering the streets back in the 1960s.)

This ambience of historical veracity likewise leverages those parts of the book that delve into San Antonio’s turbulent civic culture of the early sixties. “1961 was a crucial time for the integration of San Antonio,” Perez says. “I remember that in 1959 or ’60, Woodlawn (public) pool was integrated, but before they integrated it, some black young men jumped over the fence and swam in the pool. And the next morning, because they must’ve been filthy, they drained the pool!”

One could imagine all of this as the premise for a movie, but at 78, Perez professes to be fully committed now to his work as a novelist. “Films are exhausting,” he says. “A feature film takes at least three years from beginning to end, and it takes a lot of energy, and a lot of sucking up to people…I didn’t want my creative life to be over just because I could no longer make films.” He sees his novels as a perfect workaround, a natural transition from his work in cinema.

“If somebody were to ask me, ‘Have you given up filmmaking?’ my response would be, ‘No, I’m still making films—they just play in the theater of your mind.’”

This post has been updated to make a correction: Undone is an Amazon series, not Netflix.

- More About:

- Books

- San Antonio