Only three years ago Kelly Clarkson was working part-time for Red Bull, the energy-drink company, driving around in a little car that had an oversized Red Bull can attached to the top of it, passing out free drinks at places where young people liked to gather. She made $13 an hour. Not bad, but Clarkson didn’t hesitate to tell her customers that she had other plans. Her goal, said the recent graduate of Burleson High School, was to become a major recording artist. The customers would nod and smile encouragingly. Clarkson was five feet three inches tall, cute but not a knockout. She had a rather round face, and she didn’t look particularly sexy in a midriff-baring shirt. When she was passing out Red Bulls at Joe Pool Lake, a popular hangout outside Fort Worth, she sometimes sang to whatever song was blaring from someone’s stereo, and she sounded good. But what were people supposed to say? “Oh, yeah, you’re on your way”? She was getting out of her Red Bull car and singing at Joe Pool Lake.

Then, one day that summer, she showed up in Dallas to audition for the first American Idol, whose premise was little more than a hastily recycled version of the British reality-TV hit Pop Idol: Three judges would critique the singing of each contestant, and the television viewers would vote for their favorite performer by calling an 800 number. “What the heck,” said Clarkson. And a few months later, she won. She won the whole damn thing, including a $1 million recording contract with RCA Records. Twenty million people watched the final episode, in which tears streamed down her face as she sang “A Moment Like This,” a melodramatic ballad written just for the show. Still, though Kelly Clarkson was suddenly a household name, it wasn’t supposed to last. That’s the nature of reality television. You become a star on a show, you make some headlines, and then along comes another show and, like so many Colby Donaldsons and Bill Rancics, you’re forgotten. According to the music critics, Clarkson would be back in her Red Bull car very, very soon. And why shouldn’t they have made such claims? Nobody else had ever parlayed a stint on reality television into something substantive.

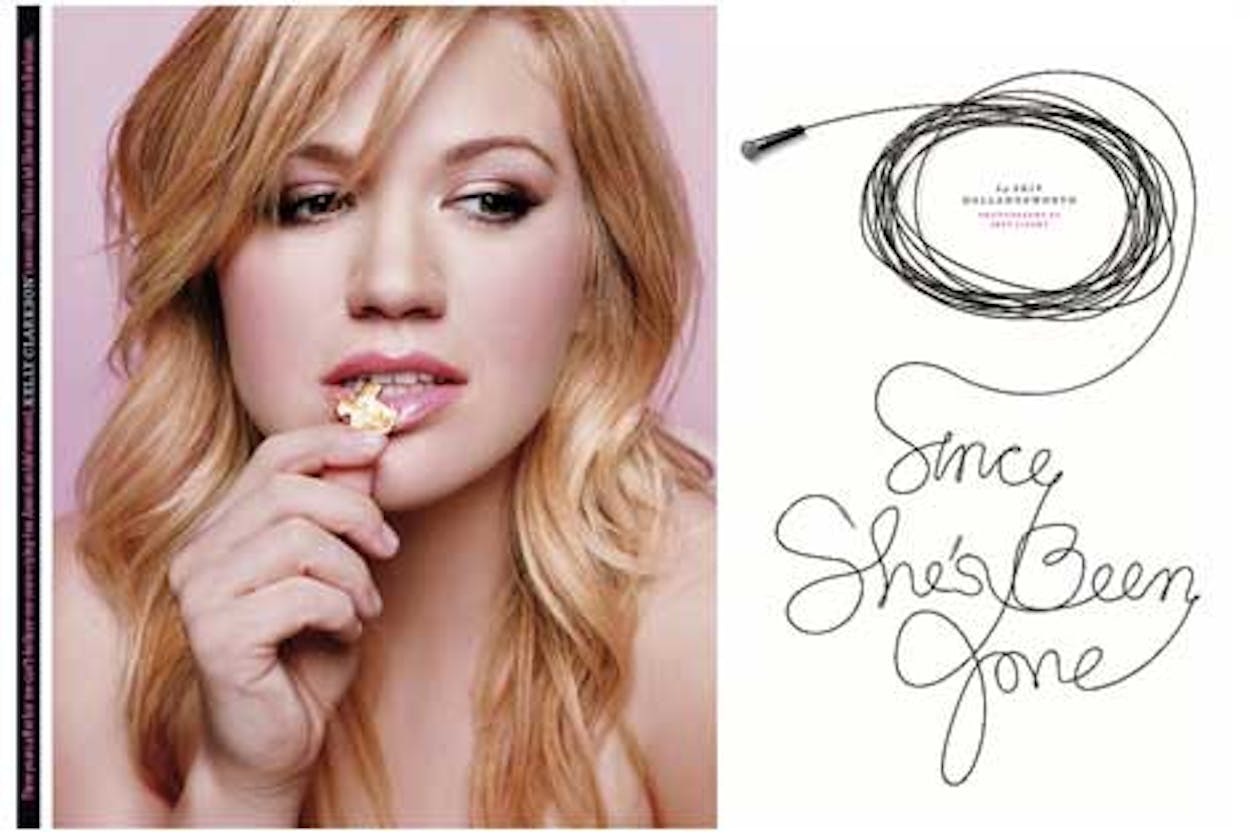

But now it’s 2005, and Clarkson is still making records. Her second album, Breakaway, is one of the best-selling albums in the country. It has already sold more than two million copies, and two of its singles, “Breakaway” and “Since U Been Gone,” are in the top ten on the Billboard mainstream radio airplay chart. She is everywhere: performing at awards shows, at halftime at the Orange Bowl, and at nationally televised concerts before the Super Bowl and the NBA All-Star Game. And any notions that she would be fading away soon seemed to disappear in February, when she landed the musical guest spot on Saturday Night Live. It wasn’t just that she was a guest on the kind of show that you would expect to lampoon an American Idol contestant. It was that when Clarkson was introduced, the host, actor Jason Bateman, didn’t say, “Ladies and gentlemen, your American Idol, Kelly Clarkson.” He simply said, “Ladies and gentlemen, Kelly Clarkson.”

In other words, Kelly Clarkson has accomplished something no other reality- television veteran—no survivor, no apprentice, no bachelorette, no amazing racer—has been able to pull off. She’s become a legitimate star. What’s more, no one else from any subsequent American Idol, a show that does require genuine talent, has been able to match Clarkson’s success. So how did it happen?

“Once Kelly realized the door had been cracked open for her, she reared back and kicked it wide open,” says Jeff Rabhan, a manager at the Firm, the Los Angeles agency that handles Clarkson’s career. But that’s just her management talking, and it doesn’t explain Clarkson’s more surprising feat: While all the other highly managed pop tarts of her generation—Christina Aguilera, Britney Spears, Jessica and Ashlee Simpson, to name a few—have learned to rely on the paparazzi and their tabloidish personal relationships to sell albums, Clarkson has remained a star despite acting, well, normal.

In fact, when I first meet Clarkson, she is sitting in a photographer’s studio in Venice, the Los Angeles neighborhood right next to the beach, wolfing down some pasta before she has to go behind a curtain to get dressed for a photo shoot. She is wearing a loose-fitting T-shirt, white capri pants, flip-flops, and a black-and-white-checked hat, the kind that former Alabama football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant used to wear on the sidelines. There is not a stitch of makeup on her face.

“Kelly,” calls out a woman from the other side of the room. It’s Emma, Clarkson’s wardrobe consultant, a member of what an executive from RCA Records describes as “Kelly’s glam squad.” Besides Emma, another young RCA-hired woman is there to do Clarkson’s hair and makeup.

“How’s this?” Emma says to Clarkson, holding up a black dress.

Usually, the process of choosing an out fit for a celebrity photo shoot lasts about as long as an Oscars telecast. The celebrities and their handlers fret over the meaning of the outfit and what image it conveys. Arguments ensue. Dozens of outfits are tried on and discarded before one is finally chosen. Clarkson, however, looks at the dress Emma is holding for maybe five seconds. “Great!” she says before turning back to her lunch. “Love it!”

Sitting across the table from her is her brother, Jason, who’s 31, a congenial teddy bear of a guy Clarkson hired last year to be her personal assistant. Jason not only lives with Kelly, but he also drives her to all of her appointments, flies with her to concerts, deals with the phone calls from her managers and agents, and handles her fan mail: thousands upon thousands of letters that he keeps in boxes in his bedroom.

I ask Jason what he did before working for his sister.

“I was living in Alaska, working as an electrician and running a part-time janitorial service,” he says. “Then I went through a divorce, and Kelly said come on down, she had something for me to do.”

“You know,” I say to Clarkson, “there are people in L.A. who are professional personal assistants, all of them very good with Palm Pilots and Day-Timers and that sort of thing.”

“Good Lord!” she says. “You really think I’d hire someone like that?”

Clarkson lives not far from the photographer’s studio in a two-bedroom apartment, close to the Pacific Ocean. She sleeps in one of the bedrooms. Jason sleeps in the other bedroom. Clarkson’s childhood friend Ashley Donovan, who used to work with her as a ticket-taker at the movie theater in their hometown of Burleson, sleeps on a mattress in the cramped upstairs loft.

Because Clarkson doesn’t cook, there is almost nothing in the refrigerator except bottled water and packaged turkey. In the freezer are frozen grapes, which she likes to suck on whenever she gets a sugar craving. The living room, which needs a new coat of paint, contains a stereo, a television, and a big brown couch—“thrift storish” is how she describes it—and on the walls are two colorful abstract paintings that she bought for next to nothing at a flea market. Her bedroom consists of a king-size bed set on a gigantic wooden frame. What floor space is left is covered with pairs of Chuck Taylor All Stars, T-shirts, blue jeans, stacks of CDs, and a couple of half-packed suitcases. She tells me her bathroom doesn’t even have a mirror.

“I know, I know. Everyone tells me that the time has come for me to act like a diva,” she says, shrugging her shoulders. “But to be honest with you, I never brush or blow-dry my hair unless I’ve got to be somewhere in public.”

Ashley arrives at the photographer’s studio and takes a seat at the table. I ask her how her life has changed since she quit her job as a waitress at an Outback Steakhouse in Fort Worth and moved to Los Angeles last year at Clarkson’s urging.

“Well, if you want to know the truth, what we really like to do is just hang around the apartment, staying up late and talking and watching reruns of Kelly’s favorite shows, Friends and Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman,” she says. “Don’t ask me why, but she loves Dr. Quinn. And some nights we do get in the car and cruise around. Just the other night we were in the car trying to make a movie, but we missed it. So we ended up at this run-down bowling alley near our apartment. Kelly said, ‘Hey! Bowling!’ And so that’s what we did.”

“How many really great parties have you been to?” I ask.

“Well, we do like going to Chili’s, even though it’s pretty far from our apartment. Kelly always orders chips and salsa with a bowl of ranch dressing.”

Reporters tend to assume that any attempt by celebrities to be modest is simply an act to mask the breadth of their ambition or their controlling natures. Yet it is hard to spend time with Clarkson without wondering if she even realizes she has moved to Los Angeles. By most accounts, she spends all of her free time with Jason, Ashley, or a small circle of other friends who she tells me are “completely outside the industry and not obsessed with discussing what Justin Timberlake is really like.” Not only does she go to very few industry parties, she has the kind of personal life that does not remotely interest the tabloids or the other celebrity-driven magazines. She says she dislikes going to trendy bars because of the way men talk to her. “Guys hit on you in L.A. like they are selling you a fully loaded car,” she says. “They always want to talk to you about all the stuff they have.” She does tell me that she had a boyfriend for a while (she wouldn’t identify him), but then she says they didn’t really date. “Well, we had one date. We went to a very good restaurant and ate something called lobster something. But almost every other night we just hung out with my friends at the apartment.”

Nor will the magazines feature Clarkson in one of their periodic stories on how celebrities stay in shape. She doesn’t have the requisite personal trainer, to help her try to reduce the size of what she describes as “my big butt.” She does some sit-ups and occasionally walks on her treadmill at home. Every now and then she goes with Jason to a public park near their apartment, where they lob tennis balls at each other on a crack-lined court with a metal net. But that’s about it. Probably the best chance you have of spotting Clarkson in an Us Weekly is in one of the wholesome “Got Milk?” advertisements she’s agreed to do, which are supposed to start running this spring.

Clarkson was raised in Burleson by her mother, a first-grade schoolteacher, and her stepfather, a contractor. (Her father, a car salesman, has lived in the Anaheim area of California since he and her mother divorced, when she was six years old.) She says she spent most of her childhood singing. She spent so much time singing, in fact, that Ashley put a karaoke machine in Kelly’s closet, stuck a sign on the door that read, “Kelly’s recording studio,” and sat in a corner of the closet while Clarkson held a little plastic microphone and wailed away to such glass-shattering tunes as Mariah Carey’s “Vision of Love.” Although she never had formal singing lessons, she definitely had talent. When she sang a solo with the junior high school choir, she received a standing ovation, and in high school she received rave reviews from the audience when she played the role of Fiona in a school production of Brigadoon. “I didn’t want to go to college,” Clarkson says. “My goal was to be a major recording artist. And when I told my mom, she never once discouraged me. She said, ‘Kelly, you can do it.’”

After Clarkson graduated, in 2000, one of her friends, Jessica Hugghins, gave her some money to cut a demo tape. Clarkson then took on extra jobs—besides working at the movie theater, she also worked at Eckerd and as a waitress at a comedy club—to afford a trip someday to Los Angeles or New York to visit music producers and launch a career. To save money, she went with her friends to Chili’s, where she would eat chips for free and nibble the leftovers on everyone else’s plates.

The problem, of course, was that there were literally hundreds—maybe thousands—of talented kids graduating from American high schools in 2000 who believed the very same thing about themselves. They too had been told by their friends and their proud mothers that they were the next big thing. They too were cutting demo tapes. And only the tiniest fraction of them were ever going to get the chance to show off their talent, which seemed to be precisely the fate that was about to befall Clarkson.

She finally made her trip to Los Angeles in late 2001 with a girl she had met when the two of them performed at a music show at Six Flags in Arlington. For a while, they rented a small bedroom in a home near Hollywood, and then they moved to a rattrap apartment off Melrose Avenue. When she was not auditioning for producers, Clarkson paid the bills by working as a waitress and appearing as an extra in such shows as Sabrina, the Teenage Witch and Dharma & Greg, standing in the background for about $70 a day.

In truth, there was some interest in her as a singer. A Los Angeles songwriter who had once penned songs with Carole King said he wanted to use her as a backup singer for his next recording. But that didn’t lead anywhere. When she went to audition for other backup singing roles, some producers told her that, though they liked her voice, she was either too small or too heavy for live shows. One producer told her to lose eight pounds. Another told her her voice sounded “too black.”

When Clarkson’s apartment caught fire in the spring of 2002, destroying all her possessions—she stood on the sidewalk in red pajamas and flip-flops, watching the building burn—she tried to hang on for a couple of days. She lived in her car—she was then driving a Ford Explorer with a huge dent in the rear end—and she took showers at a gym. But she eventually went broke and headed back to Texas, driving the entire way nonstop and writing hot checks to pay for her gasoline.

And that seemed to be that. But Clarkson says she was not the least bit discouraged. “Oh, heck no. I assumed something else would come along,” she says. But even the optimistic Clarkson couldn’t have guessed how quickly the next opportunity would present itself. Within days of her return, the mother of Jessica Hugghins, the girl who had paid for Clarkson’s demo tape, told Clarkson about auditions for American Idol at Dallas’s Wyndham Anatole hotel.

It was 2002, and American Idol was still considered to be just a summer novelty show; one critic described it as “a sadistic musical bake-off.” But because Fox promised the winner a $1 million recording contract with RCA, the auditions around the country were packed. Clarkson, her auburn hair streaked with blond, arrived at the Anatole at sunrise to perform—she had to be at her Red Bull job later that afternoon—and she sang the Aretha Franklin song “Respect.” In his memoir, I Don’t Mean to be Rude, But . . ., the snippy English judge Simon Cowell wrote, “There wasn’t anything about her that jumped out at us at that point . . . She was just a girl with a good voice.” Even when she was named one of the thirty finalists out of the Dallas audition, the Dallas Morning News and Fort Worth Star-Telegram reporters covering the auditions seemed more entranced with the other finalists, including a former Dallas Cowboys cheerleader and a cute redheaded single mom from Grand Prairie who spent her evenings singing at a karaoke bar.

But Clarkson continued to win over the television audience. And although Cowell’s favorite performer that year was a black singer named Tamyra Gray, whom he described in his book as “as close to perfection as you could possibly get,” her performances filled with “incredible acts of showmanship and technical mastery,” he admitted that he found himself admiring what he called Clarkson’s “normality.” She had a down-to-earth charm when she bantered with the judges and the show’s hosts. And the fact was that she was also very good during those pressure-packed last shows, adding breathy verbal melisma at the ends of lines and taking her voice from a whisper to a full-throttled roar before each song was over.

To hear Clarkson tell it, she can hardly even recall the now-legendary moment when she belted out her tear-drenched rendition of “A Moment Like This” in the first season’s final episode. “I was so exhausted from the competition I didn’t know I was crying until I watched a tape of the final show a few weeks later,” she says. “Isn’t that funny? I don’t remember a bit of it.”

The music critics were predictably merciless. Thor Christensen, of the Dallas Morning News, wrote that Clarkson’s rendition of “A Moment Like This” made Mariah Carey and Celine Dion “look like twin pillars of subtlety and restraint.” When she performed the National Anthem at the Lincoln Memorial during a September 11 charity event, the Washington Post’s television critic sniped, “The terrorists have won.” Almost everyone began taking bets on when she would fall on her face.

The stumble they were waiting for seemed to happen during the spring of 2003, when Clarkson and the show’s runner-up, the fuzzy-haired Justin Guarini, starred in a movie, From Justin to Kelly: The Rise of Two American Idols. An utterly inane project, it was rushed into theaters to take advantage of the singers’ popularity before the second season of American Idol began and a new winner was crowned. And though it was designed to appeal to young teenagers—Clarkson and Guarini acted like a modern-day Annette Funicello and Frankie Avalon, dancing around on a beach, singing happy songs, and giving each other playful looks—it bombed at the box office. Clarkson tells me she did everything she could to get out of the movie, but the contract she signed when she joined American Idol mandated her participation in the project.

Yet even then, she says, she was not worried that her career was over as soon as it had begun. “I was just not going to let myself fail,” she tells me. Indeed, one RCA executive says that Clarkson was “a relentlessly hard worker” in the post–American Idol days. “She never once had to be told that she was going to have to keep waking up every day and proving herself,” he says. “Despite all of her sudden fame, she knew what it took to break a record and establish a career: not just one television show but constant promotion and constant performing.”

And what almost all of the critics missed was the way pop music lovers responded to Clarkson’s singing. This was a girl they got to choose to be a star, not someone a record company had chosen for them. “A Moment Like This” became the top-selling U.S. single of 2002, selling 600,000 copies, an amazing feat considering how moribund the singles market is in this era. And when her first album, Thankful, was released in April 2003—far too late to capitalize on her popularity, some music insiders said—it went to number one on the Billboard 200 within a month. A single on the album, “Miss Independent,” even garnered Clarkson a Grammy nomination.

Still, it was hard to fathom how the Burleson girl next door could remain the girl next door. How can anyone experience such a stratospheric rise without it going to her head?

“Okay, there was this one time,” she says. “After American Idol, I did nothing but live in hotel rooms in Los Angeles for a long time, and all I did at night was watch the in-room movies, over and over and over, and I said, ‘This is so horrible. I want a place for my friends to visit me.’ So this real estate agent showed me Al Pacino’s former home on South Rodeo Drive, right in the heart of Beverly Hills, within walking distance of the Beverly Wilshire Hotel and all the boutiques and all that. It was completely furnished, with that kind of really expensive leather furniture. I kept thinking, ‘Not me, not me.’ I didn’t have enough clothes to fill up the master bedroom closet, and I knew my Ford Explorer would look like crap in the driveway, and I wanted a couch I could lay down on. But I just wanted to feel like I had a home. I said, ‘Okay, I’ll take it.’ Then I called Ashley and said, ‘Hey, come on out.’”

“I took one look at the place,” says Ashley, “and I asked Kelly what she was paying. When she told me, I said, ‘Uh, Kelly, for that price you could buy a car every month.’”

“And I just looked at Ashley,” says Clarkson, “and I thought, ‘I’ve got to get out of here. I’ve got to get out of here.’”

In a later conversation, she offers perhaps a more meaningful explanation of why she is in that apartment and why she has no immediate plans to move: “I’m worried that if I try to become something I’m not, then I know everything else is going to get screwed up.”

Clarkson is certainly not oblivious to her financial bounty. She took all of her best Burleson friends to Hawaii, and she bought her friend Jessica a Corvette as a thank-you present for paying for her demo tape. When Jason arrived to be her personal assistant, she purchased a sporty black two-door Cadillac that cost about $75,000 so they would look good when they showed up at concerts or promotional appearances. She also bought a twelve-acre ranchette south of Fort Worth, where she hopes to live part-time.

But to understand Clarkson, says Ashley, “you have to understand that deep down, she still doesn’t care about doing the trendy stuff, and she still says ‘Cool beans,’ and she still watches Friends just like she always did.”

“Maybe this will explain her,” says her manager, Jeff Rabhan. “We went to Thailand in February for the MTV Asia awards, and every day we were there, we passed by this gigantic carnival that had roller coasters and other outdoor rides. After the MTV show, there was a huge after-party, full of the biggest names. And Kelly said, ‘Come on, guys. Instead of doing what you think you’re supposed to do, do what you want.’ And she took us to the fair, where we shot basketballs, rode the roller coasters, did the bungee jump and the bumper cars.”

As soon as he tells me that story, however, he then warns me not to underestimate Clarkson’s continuing determination to be successful. “All you have to do is listen to her new Breakaway album,” he says. “I’m sure her record company and her fans would have been satisfied with another straight-ahead pop record. But Kelly is still very aware of those criticisms that she is just a one-shot American Idol singer, and she is driven to beat that stigma. On the Breakaway album, she wanted to assert her own creative flow. She wrote half the songs. She said, ‘I want to record an album with personality, with songs that have a dark side to them, a record that is louder and harder than anything I have ever done.’”

“I am not going to be pigeonholed, I promise you that,” Clarkson says. “I’m twenty-two. I didn’t just listen to Celine and Mariah growing up. I listened to Guns n’ Roses and to the Toadies and to Aerosmith.” One of the fake names she uses at hotels to keep fans from bothering her is Tyler Stevens, a flip-flop of the name Steven Tyler, Aerosmith’s lead singer. “I love ballads, but I also want my albums to rock out. And I will always want to sing bluesy, soulful songs, like Aretha and Janis Joplin. I’ve had these meetings with record executives where there is all this deep talk about how to break me out of the ‘American Idol’ label, and I say, ‘Dudes, just let me sing. It doesn’t matter to people how you got into the business. It matters to them how you stay.’”

Breakaway has made several once-scornful critics take a second look at Clarkson; though the Morning News’ Christensen still has trouble with the emotional depth of her lyrics, he wrote in a review, “Technically, she’s a first-rate singer.” But she is hardly satisfied. She tells me she is already spending many nights sitting in the middle of her gigantic king-size bed with her silver laptop, which has a software program that allows her to sing into the laptop, then play whatever she has just recorded with background music added. “Right now, I’ve got thirty to forty new songs on that laptop,” she says. “Sometimes I wake up at four in the morning, my head spinning with ideas, and I grab the laptop, which is always beside me. I’m on my third laptop since I bought the bed. The first two fell off the side and broke.”

She pauses, as if weighing whether to tell me something else. “Oh, all right, I did have this other diva moment. I was having trouble sleeping, so my managers had me fly to Canyon Ranch, this big spa in Arizona, to consult with a doctor who specializes in sleep. But nothing helped until my mom sent me one of those nature CDs that had the sound of rain hitting tin roofs and thunder going off in the distance.”

“And now you sleep like a baby?”

“Of course not. There’s still music getting inside me, waking me up.”

“She’s even bought a BlackBerry so that she can write everywhere,” says Jason. “We’ll be sitting on an airplane, and she’s typing on it, and I figure she’s e-mailing someone. Then I’ll look over and realize she’s writing a song about love or something.”

When clarkson comes out from behind the curtain for her photo shoot, the transformation is genuinely stunning. Kelly’s glam squad knows what it’s doing. The homemade blond streaks from the American Idol days are long gone. Her hair now has a perfectly stylized, just-out-of-bed look that delicately frames her face, and the black dress accentuates her curves. “I have no breasts,” she tells me, “but I do have curves.”

The photo shoot lasts for most of the afternoon. Jason leaves early to run errands and mail off a large package of Clarkson’s autographed photos. (She has vowed to autograph any eight-by-ten photo of herself that a fan sends her along with a self-addressed stamped envelope.) At some point, Clay Aiken, the runner-up in the 2003 American Idol competition, calls Clarkson’s cell phone. Aiken, who has also had a fairly good run in the recording and concert business since his time on the show, wants Clarkson to meet him for dinner at an expensive steakhouse so they can talk about their careers.

Clarkson initially says yes. Then Ashley reminds her that a group of the girls have arranged to go bowling that night. They want to try a new place called Lucky Strike, in the heart of Hollywood.

“Oh, my gosh, Ashley, please call Clay back and tell him that I just can’t miss the bowling,” she says. “He’ll understand completely.”

Clarkson, Ashley, and a couple of their friends are at Lucky Strike by nine o’clock. Clarkson is back in her T-shirt, capri pants, and flip-flops, her Bear Bryant hat jammed on her head. The place is packed, and not a single person recognizes her. When a lane comes open, she pulls on some two-toned bowling shoes and starts bowling, crying out in mock horror when she hits only two pins.

She bowls again. It’s a gutter ball. “Owww!” she cries.

She looks at me expectantly, as if she already knows the question I’m about to ask. “I couldn’t be happier,” Clarkson says, and she turns away to throw one more ball into the gutter.

- More About:

- Music

- Kelly Clarkson

- Burleson