On August 28, 2013, we talked to Richard Phillips, the artist behind the controversial Playboy Marfa installation. Read more about the art-versus-advertising debate here.

FRANCESCA MARI: When were you tapped to do this piece for Playboy?

RICHARD PHILLIPS: I was contacted before the New Year by Neville Wakefield, who is the director of the special projects for Playboy. The idea of resetting the terms of Playboy was very interesting to me. The magazine held a gateway-type position when I was growing up in the seventies.

FM: How so?

RP: I would find the magazine hidden in my parents’ house and would look inside and see this place where eroticism, politics, journalism, and literature met and could come together.

FM: What sort of project did Neville propose?

RP: Neville communicated to me that Playboy was developing a series of artistic initiatives that looked at the idea of resetting up terms. So I thought, “What is the absolute defining point in American sculpture for resetting terms?” And that is Marfa, Texas. When Donald Judd discovered the space, he made a real connection, and coming back a little bit later on and purchasing the property and then eventually moving his practice there was significant in the sense that he had reached a point where the conventional art institutions in New York City, where he had been based, and elsewhere were no longer functioning to create the kinds of experiences that he felt were on the forefront of artistic expression. Marfa was a site to reset the terms of his production.

FM: Have you been to Marfa?

RP: No. A friend of mine gave me a very important book on Judd’s architecture, which happened to have been sitting on my desk when I was having this conversation. Those particular concrete forms are favorite sculptures of mine, although I have not yet visited Marfa.

FM: So you are familiar with some of the work there.

RP: In essence, my sculptures are an appropriation of those existing forms down there, then changed subtly. I was very aware of the Art Production Fund piece Prada Marfa, which I think is a terrific work. On the set of Gossip Girl, my painting was above the staircase of the Van Der Woodsen loft, and then, you know, the Prada Marfa piece was at the base of the stairs, and so our work was seen by the four or five million people a week who watch that show.

FM: What was your assignment?

RP: To create an artwork. And to me, a sculpture seemed the most poignant form of expression.

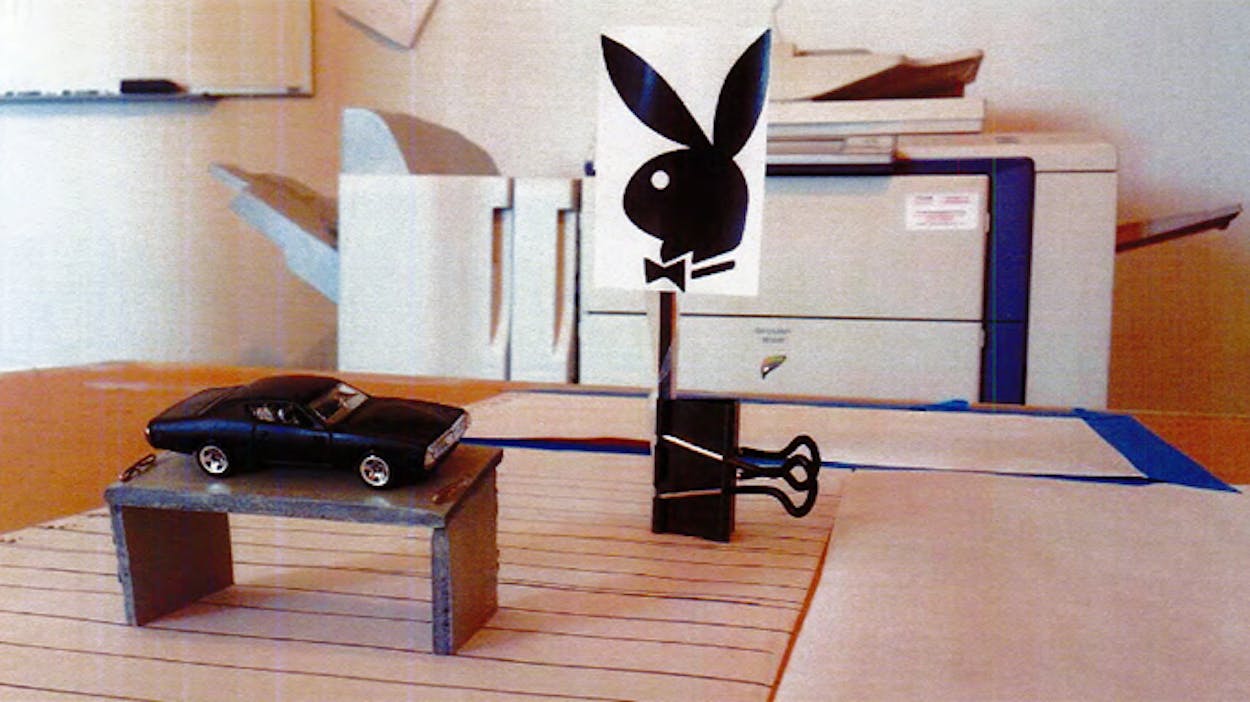

The 1972 Dodge Charger is the epitome of personal luxury and power that was made available to a much broader group of consumers in the mid-seventies. It was also the production model of the car that was developed into Richard Petty’s racecar, in which he won the Daytona 500 in 1974. The tilt of that Judd-like concrete piece is 18 degrees, which is precisely the tilt of the start/finish line in Daytona. The neon piece says, “Oh, you took that Dan Flavin piece and bent it into the shape of the Playboy Bunny.”

In 1974, Playboy reached the height of its circulation, and the Dodge Charger was the apex of the American muscle car right before the gas crisis, and 1974 is the apex of American primary-structure sculptural expression through the works of Flavin and Judd and Chamberlain.

And then there’s the concept of space and what space does to sculpture, and the limitless space that is seen in that part of West Texas where the sky becomes that fourth element of a piece—where the painted sky is a backdrop that changes from moment to moment.

FM: Why did you use the trademarked bunny logo?

RP: Since it was a commission from the special projects of Playboy—a corporate portraiture—the image of the portrayed was resolved in the illuminated bunny. How the bunny stands in conjunction with the tilted plinths is very much like a roadside attraction that you might have seen in an Edward Ruscha painting or in an Edward Hopper painting. There’s a history really, in American art, of these types of tableaus, and so my concept was to set it up very much in the same way. But at night, the illumination of the emblem serves to actually light the sculpture in a very dramatic way.

FM: So you were on the phone with Neville Wakefield, and you were sort of bouncing around ideas and you sketched—

RP: I sketched a plinth, and I sketched a car on the plinth, and then I sketched the kind of emblem of the bunny on a vertical pole right next to the plinth and the car. It was a very rough sketch, but it immediately captured the essence of bringing all those elements together. We knew what size the Judd pieces were, but we had to scale up our plinth slightly, because otherwise the car would overhang in an awkward way. We knew we would have to raise the emblem to have it be seen in the proper relationship sculpturally with the other two elements. It’s very similar to the portraits that I did where you would have a picture of Taylor Swift with a Givenchy symbol behind her head.

FM: Would you tell me a little bit about your interest in brands and these emblems?

RP: They’ve been part of my artwork for quite some time. I did a painting in 2004 of the German foreign minister Joschka Fischer, which was an interpretation of one of his green party’s political posters, and behind him was an emblem from Mont Blanc. In fact, that was a commission by Mont Blanc for an artwork that incorporated the Mont Blanc symbol, and that painting actually was installed in their corporate office as artwork. I appropriated a foreign minister and then put him in the context of a brand that he did not have any relationship with. It was a commentary on advertising spokespersonship and the idea of media communications for both countries and brands.

FM: How do you respond to people who interpreted your piece as mocking Judd and Flavin and Chamberlain?

RP: I leave open the potential for people’s own subjectivity to become an important actor in the experience of the art. To say that they’re a mockery, that would be a rather unproductive reading of the work, but one that, nonetheless, has to be accepted. In fact, it’s quite the opposite; it pays homage to the importance of that work, but in a new and different way. I wasn’t seeking to outright appropriate them and remake them, but it spoke to the spirit from which those works came from.

FM: Were you the one who proposed Marfa?

RP: Yeah, it was about the idea of this kind of finding a space for sculpture. It was me in the context of the great works that are down there. Marfa is one of the most important sites in the world. It is a global reference point at this moment in time.

FM: The opening took place at the Standard Hotel in New York on June 19. What was that like?

RP: You know, it’s the first time, I think, that I’ve done a kind of offsite opening before, to that degree. But it was nice. There was a group of people from the art world and from media in New York, and Neville was present with his team that has been giving the artistic initiative, and then I was there and also the planners from Playboy, the CEO, and Raquel Pomplun, who is the Playboy bunny of the year, who was photographed with the sculpture in Marfa and who I had not met before. I gave a talk on the work, and there were images shown in a short film that was made by a photographer, Adrian Go.

FM: How did people react to the work?

RP: I got a very positive sense. I’ve seen a lot of people Instagramming and tweeting from that site. There were shots at sunset, and there was even an image of the piece with a double rainbow. I think that one of the functions of the sculpture is that it is this offsite site, so that if you’re there, it becomes something that’s relevant to social media. As much as it’s an offsite piece that can be seen in images, it’s very much about the experience of being there, and I’m looking forward to having that.

FM: Will there be an opening in Marfa?

RP: The piece has kind of officially opened. There was never any intention of having a ribbon-cutting or anything like that. The piece was meant to appear and to make its presence by having people pass by or see it or hear about it or see images of it. It was very much about igniting a discussion about art.

FM: Were you surprised by the fervor of the discussion that was ignited?

RP: No. If you make work and you present it in the public sphere, then there is bound to be discussion. I welcomed all points of view, even those that seriously questioned all dimensions of the artwork. That’s what art as a language can do better than any other form of language, why it is the most important form of communication that has lasted throughout time.

One of the more interesting critiques was that someone knew Daytona happens to run counter-clockwise, so the Charger is actually facing backward, and they were wondering whether that was on purpose. I think somebody tweeted that at me. That’s where I was careful not to make specific statements about the literal elements of each of the pieces. But if you dig further into each of the constituent forms, you do find that there are stories behind them, including the presence of the bunny, and where it’s been positioned around the world, and how’s it’s related to art and to motor sport culture.

FM: How do you respond to the criticism “This isn’t art, this is advertising”?

RP: Well, it’s not advertising. That’s what I would say. I am an artist, I was not contracted to create an advertisement. I created the artwork as a singular expression, and it cannot be taken apart—“this part is art and this part is advertising.” Emblems have long been a part of artistic creation, from Warhol’s soup cans to the Stuart Davis paintings with the Champion spark plugs. Emblems are developed by people, and we tend to kind of overlook that. The presence of trademarked logos in art is protected by the First Amendment.

FM: To be clear, when you were conceptualizing the piece, did Playboy ask you to include the logo?

RP: To be absolutely clear, that was my own initiative. In the history of my work, I often have used trademarked logos. In the case of my “Most Wanted” paintings, I did so as a fair use commentary on our cultural condition.

FM: Are you working on phase two of the arts initiative right now?

RP: Yes, we’ve been working on phase two for some time, and I’m looking forward to making that known in the near future.

FM: Is it going to launch in Marfa or elsewhere?

RP: Elsewhere, definitely.

FM: This summer, on August 6, you flew down to Austin to participate in this meeting between Playboy and the Texas Department of Transportation to discuss the order of removal.

RP: I went down there, yes, and we had what I thought was a very good meeting. To have the opportunity to come down and speak to the Texas Department of Transportation and their representatives about my art was a privilege, in a way.

FM: What was it like to participate in a meeting with a government agency?

RP: I treated it very much as I treat any type of discussion of my artwork. And I’ve done that in philosophy departments, I’ve done that in high schools, I’ve done that in Ivy League colleges.

FM: Have you dealt with similar regulation in the past?

RP: No.

FM: I wasn’t allowed to interview you for two months. What was the reason for Playboy’s silence when this controversy first erupted?

RP: I don’t know if I would call it silence. I think that it was important to listen and understand what the concerns were regarding the artwork there and then to be able to have an environment to have a productive discussion. I’ve also been very busy. I’m working on two exhibitions. One is for the Dallas Contemporary, which is coming up in May 2014, which I’m very excited about. It’s my first survey show in an American institution.

- More About:

- Art

- Donald Judd