A St. Vincent album drop is as much about the latest costume that Annie Clark is trying on as it is about the music. With her past two releases, as she gained an increasingly large following, she transformed into (by her own account) a near-future cult leader (for 2014’s St. Vincent) and a dominatrix at a mental institution (for 2017’s Masseduction). It’s not just a promotional shtick. Even if the particulars of what it means to inhabit these creative personae are fuzzy, they all work as part of a greater oeuvre, carrying through themes visually, sonically, and even in her live performances. On her Masseduction tour, Clark had an unwavering commitment to latex bodycon suits, and a faceless guitar tech meekly brought her guitars out, all but laying them at her feet.

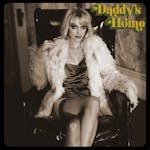

For the release of her sixth studio album, Daddy’s Home, the Dallas-reared musician instead embraced a moment in time: the seventies. Early singles garnered comparisons to the original musical chameleon, David Bowie, and a slew of other artists prolific in the early and middle part of the decade. The album cover revealed her slouching in a fuzzy coat, slip dress, thigh-high stockings, and a cropped blond wig. Promotional videos and images nailed the intended aesthetic: Clark told Rolling Stone in February that she was inspired by “the color palette of the world of Taxi Driver” and “Gena Rowlands in a Cassavetes film.”

The resulting album is a lush audio buffet and a sharp departure from the art-pop Clark has honed in her past two LPs. Lead single “Pay Your Way in Pain” mostly closely resembles the dystopian dreamscape heard on Masseduction, if hit with club drugs and viewed in black and white. But much of the rest of the album is noticeably more demure. “Live in the Dream,” a six-and-a-half-minute Pink Floyd–inspired journey, trips along with blooming melodies and glittery guitar that finally snaps into blistering focus. (If there were any way for the musical reference to be missed, she begins the song with an unmistakable “Hello,” nodding to “Comfortably Numb,” and the next song references the “dark side of the moon.”) The smooth bass line of “Down and Out Downtown” opens up into surreal layers of sound, coasting over a hazy New York after a night out at the bars.

Clark and producer Jack Antonoff clearly had fun with Daddy’s Home. There is sitar (a lot of sitar), there are mellophones, and there is a Greek chorus of backup singers, including Donny Hathaway’s daughter Kenya. There are musical references and inspirations you could argue about for days. It’s an anachronistic joy.

After mental institution dominatrix, the seventies in New York—the city where Clark now splits her time when not with family in Dallas—should have been easy enough to convey, as a broad inspiration rather than an album-specific identity. And judging by the festival success of bands like Greta Van Fleet, who, despite their protestations about the comparison, often sound like a carbon copy of Led Zeppelin, plenty of listeners are here to embrace nostalgia.

And yet, among the entire St. Vincent discography, the rollout of Daddy’s Home seems to be the most confusing for both fans and critics to parse.

That’s largely because of another component of the buildup to the album’s May 14 release: Clark’s father was released from prison in 2019, after serving ten years for his involvement in a multimillion-dollar penny-stock manipulation scheme. And now that, well, Daddy’s home, this song collection mines the seventies albums they listened to together when she visited him in Oklahoma, where he moved after his divorce from Clark’s mother.

Clark, often famously bored and frustrated with the press, has made sure to underscore that she never wanted to share the story of her father’s incarceration, which first publicly surfaced in a 2017 New Yorker profile. When writer Nick Paumgarten asked if she felt shame about her father’s crimes, she said, “Shame? Not at all. I didn’t do anything wrong. It’s not my shame.” Daddy’s Home was her attempt to lean into this family trauma on her own terms. She needed a way to, as she told NPR, tell her own story with “humor and compassion and not the kind of salaciousness” you might find in a “tabloid story.”

Early reviews and interviews have focused on the tiny autobiographical glimpses Clark gave us, often trying to shoehorn the album into a neatly packaged family story. And when that fails, critics have fallen all over themselves talking about the album’s retro pastiche—which, to be fair, is prominent, as if we’re plunked on a shag carpet, flipping through her dad’s vinyl collection. But the artists she drew from, including Steely Dan, Pink Floyd, and, hell, even Bowie, arguably never had to answer for themselves in the tell-all way that we expect Clark to.

If the men named by critics and the musician herself have been the noted musical influences for the album, women are the lyrical inspiration. These songs are full of odes to female artists and creators who “were maligned for being brave and speaking out,” Clark told Bustle. Joni Mitchell, Nina Simone, Marilyn Monroe, and Tori Amos all make appearances in “The Melting of the Sun,” a dinner party of tough women set to a warbly ooze of Wulitzers and sitar. (“Saint Joni ain’t no phony / Smoking Reds where Furry sang the blues / My Marilyn shot her heroin / ‘Hell’, she said, ‘It’s better than abuse.’ ”) A shout-out to long-departed Warhol superstar Candy Darling, a transgender actress and Velvet Underground muse, brings the album to a close, a wistful, key-driven offering to the woman Clark deems the “queen of South Queens”: “Candy, darling, I brought bodega roses for your feet.”

Darling and Monroe epitomize the glamour we bestow upon women who die young, who weren’t here long enough to take control of their own narrative. They are remembered largely for their beauty and ability to embody the desire projected onto them by others. Mitchell, Simone, and Amos, on the other hand, enjoyed (or continue to enjoy) long lives and robust careers. They’re part of a canon of songwriters that Clark almost surely hopes she will be able to join.

But Clark, at present, seems to fear landing in the gulf between these two groups—unable or unwilling to tell her own story as she wants it told, and fearing that her work alone won’t be enough to speak for itself.

That anxiety would explain the tension in Daddy’s Home. Despite the album’s title, the lyrics are only vaguely personal; listeners will find meaning in them only if they already know the story, one Clark has been asked about countless times on her current press junket. And she fills that distance between wanting to claim her own story and wanting privacy with wall-to-wall seventies nostalgia to the point of distraction at times. That’s perhaps by design, but it’s still jarring. Clark’s commitment to world-building brings the otherwise lovely slow turn “The Laughing Man”—brushed with steel guitars, brimming with ethereal guitar work—to a grinding halt with a line: in a tender moment of reflection with a childhood friend, Clark sings of “half-pipes and PlayStations.” It’s an uncomfortable jolt into the present.

But the greatest moments of Daddy’s Home come when she forgets the theme almost entirely. Even then, those moments are centered on the cultural norms that we expect of women. In the chunky, lyrical slow-build of “My Baby Wants a Baby,” punctuated by more of the slick production but this time with more cherry-picking, the narrator explores her own guilt about not being fully onboard with a partner who’s ready to settle down and start a family. She frets that her child might inherit her eyes and her mistakes, about how the responsibilities of parenthood could fundamentally alter her focus: “But I wanna play guitar all day / Make all my meals in microwaves / Only dress up if I get paid / How can it be wrong?”

For most men, being great is enough to merit whatever distance their genius requires. We’ve celebrated and valorized famously reclusive or prickly men, reminding ourselves that tolerating their egos and their mistakes is all part of the process. For years, Clark has railed against the idea that female songwriters must be confessional, and her own mechanisms for avoiding that have been clear. Whether Clark returns to her more developed caricatures on future albums remains to be seen. But she’s given us a peek behind the mask, even if it’s at a distance. In a different world, she wouldn’t have to.

- More About:

- Music