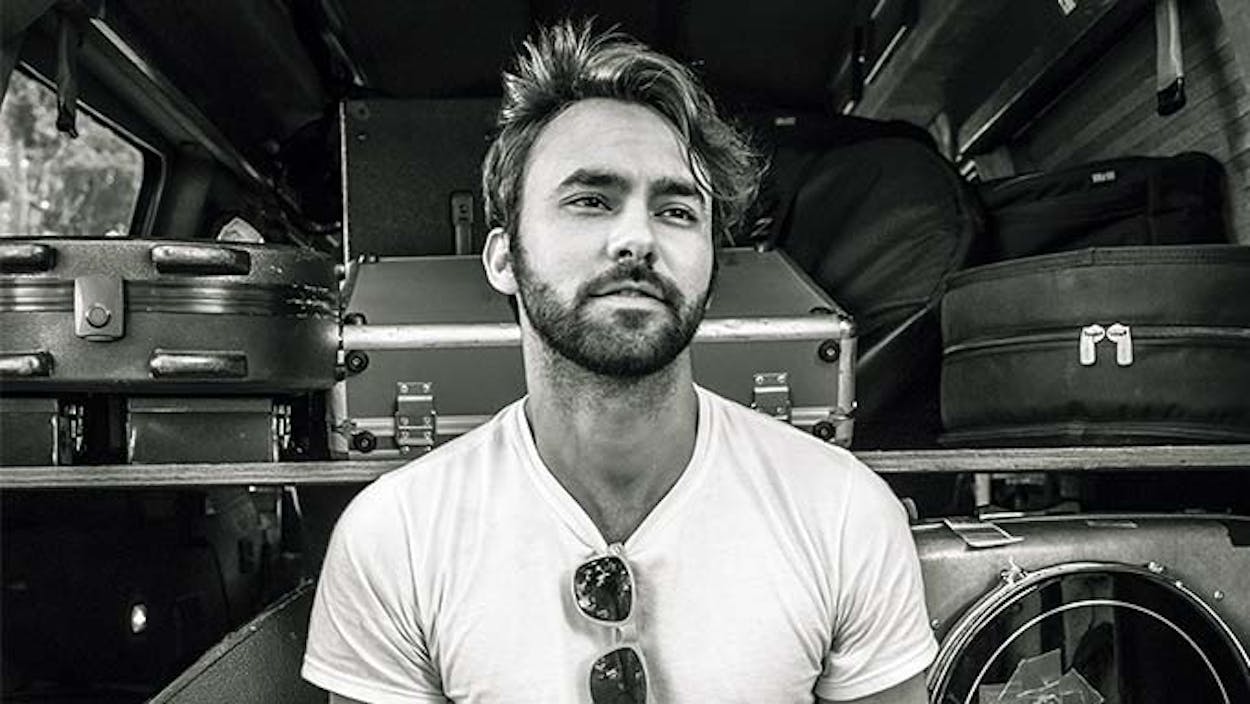

The most intense gigs are the small ones, he says. You can see the audience’s eyes, read their expressions, hear what they’re screaming between songs. He’s played a lot of those shows and finds the intimacy invigorating.

This afternoon in mid-June isn’t one of those shows. This is the kind of gig where you can barely see anything beyond the glare of the floodlights or hear anything more than the crowd’s dull roar of approval or expectation. “Lean in and hope that what it feels like in your brain is what’s actually happening,” he remembers telling himself.

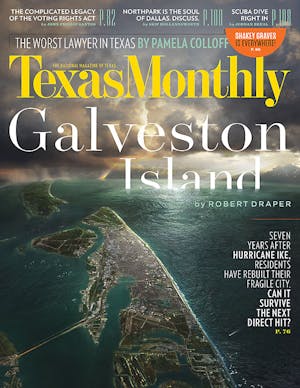

This is Bonnaroo, a four-day, 90,000-person gathering an hour outside Nashville that’s one of the most important dates on the summer music festival circuit. And Alejandro Rose-Garcia, a.k.a. Shakey Graves, is leaning in to a Bonnaroo audience so large he can’t make out where it ends. Fans are spilling out of the vast tent on all sides; officially, it holds 15,000 people, but there are significantly more folks here today, a draw that puts him in league with big-name Bonnaroo acts like D’Angelo and Slayer. Unexpected? Maybe. Young folksingers don’t typically draw crowds this big. But Rose-Garcia planned for this, built his way up to it. More than once, he had to rattle himself out of his comfort zone to get here.

“I want to play on stages so large you can barely see me, but I can still make you feel like it’s just us in a bathroom together,” says the 28-year-old born-and-raised Austinite. “To me, the coolest challenge in the world is finding a way to connect intimately with the masses.”

For two years now, festivals like Bonnaroo have allowed him to test his ability to make a lot of fans in 45 minutes or less. Summerfest. Stagecoach. Firefly. If an event has multiple stages, craft beer, and funnel cake, Shakey Graves has played it. This summer, during the four months that separate Bonnaroo and October’s Austin City Limits Music Festival, he’ll play nearly a dozen festivals. That’s an impressive run for a guy whose most recent album has sold a hardly earth-shattering 40,000 or so units over the past ten months. But this is the new music industry economy, where record sales mean less than ever and an artist can build a career on the festival circuit rather than the Billboard charts, especially if his live show leaves people believing they just found their new favorite band. And a Shakey Graves show has the goods: there are peaks, valleys, false stops, and sing-alongs, sometimes all in the same song. It doesn’t hurt that he has an affable stage presence that’s one part Dave Grohl, one part Lyle Lovett—he’s just as charismatic in what he calls “jump-around mode” as he is with a slow-simmer acoustic approach.

Last summer, when Rose-Garcia was still a cult artist, he played the Sasquatch Festival, outside Seattle. He was relegated to the small stage, where he might have been expected to draw four hundred or so people. Instead, he played to four thousand. And when he returned to Seattle on his own tour six months later, word had gotten around, and he sold out his show. That sort of thing has happened to him in city after city: play a festival set that draws in your fans and some people who wandered over from a Gary Clark Jr. set they couldn’t get close enough to, knock everyone’s socks off, and then return to town a few months later, where old and new fans alike show up for your tour gig. And when the festival comes around the following year, your growing fan base gets you placed on a bigger stage. Rose-Garcia isn’t the only artist to work this dynamic, but he’s been unusually successful at it. This year Sasquatch didn’t just invite him back, they let him skip the midsize stage and go straight to the main one. These days, people who can’t get close enough to a Shakey Graves set are being forced to wander over to check out some other under-the-radar act.

As recently as six years ago, Rose-Garcia didn’t even think of himself as a musician. He grew up in the Austin theater community; his mother is an actress and playwright, and his father road-managed Jaston Williams and Joe Sears’s Greater Tuna series. “The hyper-dramatic gay theater world was the backdrop for my childhood,” he says. He was acting in commercials by the time he was five and at sixteen dropped out of school to head off for Los Angeles. He mostly found rejection there but landed roles back home when he’d return to visit—including “the Swede,” his recurring character on NBC’s Friday Night Lights. In between auditions, he practiced guitar and tried his hand at writing songs.

“Music kept reminding me how much emotion I didn’t have an outlet for,” says Rose-Garcia. “Los Angeles can tear down your confidence, leave you sad and confused, and I didn’t have anywhere to put that. You can find catharsis from acting, but reading other people’s lines, playing out other people’s lives, makes it a terrible place for therapy.”

By 2010, after building up the confidence to play a handful of small clubs in Los Angeles, Rose-Garcia was ready to commit to music. “I swallowed my pride and moved back into my mom’s house one last time,” he says. He quickly secured a weekly happy-hour slot at the aptly named Hole in the Wall and vowed to play as many house parties and opening slots as he could book. He homed in on what would become his trademark sound—not-so-subtle shifts between plaintive fingerpicked folk and boomy blues—and perfected his one-man-band setup, which involved playing a guitar and stomping on a drum pedal attached to a vintage Samsonite suitcase. Buzz slowly built around his 2011 debut, Roll the Bones, even if the only place you could hear it was on Bandcamp, a pay-what-you’d-like online music store. Rose-Garcia already felt as though he had been building a fan base that was invested in the notion that it had discovered him; making the record something you had to search for seemed like a natural next step.

“Maybe I was snobby about it,” he says. “But I listened to a lot of DIY hard-core vinyl as a kid, where people would hand-screen the packaging and maybe there’s seventy copies in the whole world. Then it becomes something you were proud to find on your own. I thought what I was doing was the digital version of that kind of approach.”

The dark, desolate Roll the Bones was rooted in a place of existential uncertainty Rose-Garcia traces back to a 2005 experience in Los Angeles with psilocybin mushrooms. “I had a mental shift,” he says of the trip. “I became acutely aware I’m about to die. I heard a booming, godlike voice asking, ‘What do you need to do before you go?’ I sobered up the next day, and my vision had changed. It’s like I had a new pair of eyes. And it’s still the most important thing that’s ever happened to me.”

For the next three days, Rose-Garcia went on a walkabout in Los Angeles, preaching a doomsday gospel until police intervened and had him admitted for observation in a mental hospital. It’s an experience he rarely talks about at length.

“When I got out, I started making weird, cryptic music, compulsively,” Rose-Garcia says. “I used to draw all my inspiration from what I call ‘veil piercing’—the thin line between ‘Are you crazy?’ and ‘Maybe everything is okay.’ It was dark, but also kind of playful, like, ‘Maybe we’re dead, maybe we’re not, who cares?’ Shakey Graves became about my relationship with those kinds of questions.”

While some of those unanswerable questions are also present on his follow-up record, last year’s And the War Came, sonically it’s a whole different beast. Rose-Garcia has largely left the one-man-band shtick behind, adding musicians for a fuller sound. To his surprise, he’s gotten a terrific response from critics and fans alike, none of whom have expressed betrayal that he has gone for a more conventional lineup.

As gratifying as that sort of feedback is, Rose-Garcia knows that albums aren’t what he’s going to build his career on; he’s a creature of the festival circuit. And yet sometimes he asks himself, “What if I had a hit?” Would that get him to the stages so big—arenas, stadiums—most of the audience wouldn’t be able to see him at all? He’s not sure. But he’s certain of one thing: it would be a big mistake to put the brakes on now.

“This would be the absolute wrong time to say, ‘Maybe I need some time to myself,’ ” he says. “I want to burn the world down.”

- More About:

- Music

- Austin City Limits