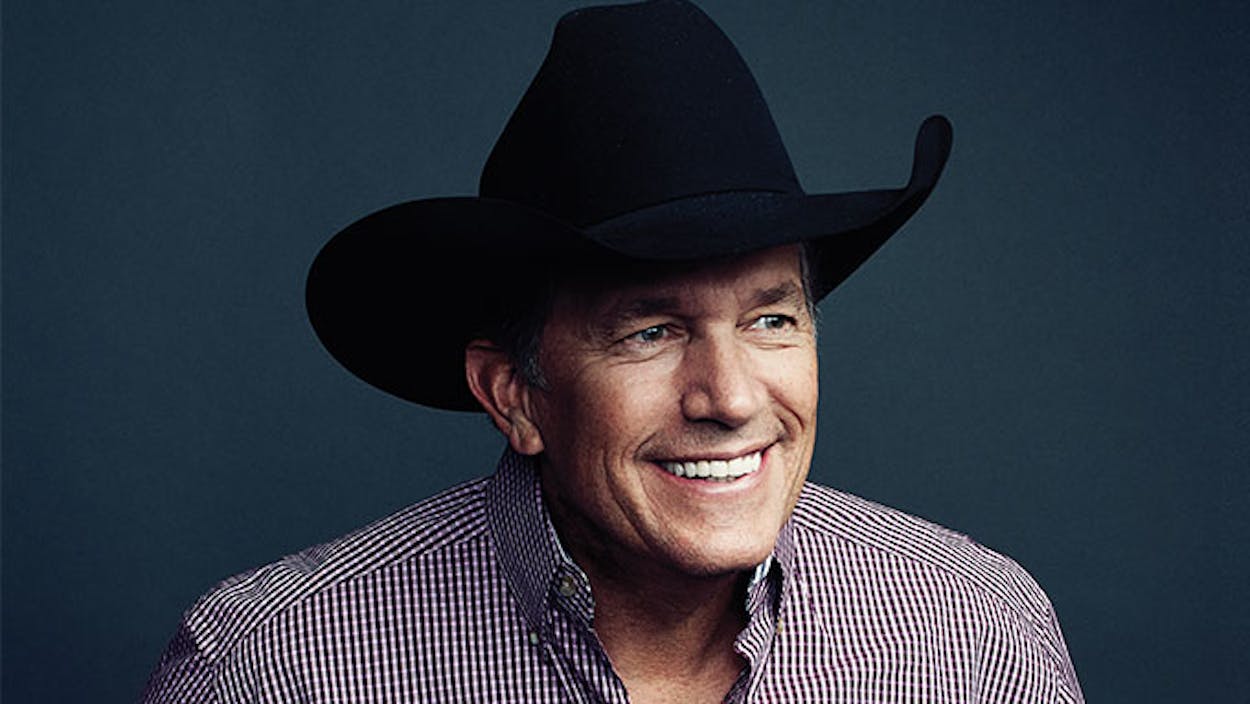

The Academy of Country Music Awards show is one of the industry’s annual pageants of who’s on top. It vies for stature with the Country Music Association Awards show, and it gives a solid indication of where the business is heading and what’s preoccupying it at the moment. Case in point: the charged night of May 3, 2000, when George Strait stood onstage in Los Angeles in front of every gatekeeper and power player in the industry who made his epic career possible, strummed his acoustic guitar, and sang a scathing indictment of the system. “Someone killed country music / Cut out its heart and soul / They got away with murder / Down on Music Row.”

At that point in the song, Strait’s fellow country-music traditionalist Alan Jackson strolled out, so slowly that he juuust reached his microphone in time to sing the second verse. “The almighty dollar / And the lust for worldwide fame / Slowly killed tradition / And for that, someone should hang.”

The song was the handiwork of writers Larry Cordle and Larry Shell, traditional musicians who lamented the decline of the real country sounds. It likely would not have gotten much attention, but the perennial argument over country music’s sound, style, and integrity was unusually heated at that moment. Research showed that country radio’s long-standing, heartland audience was abandoning the format in droves, to be replaced by younger, more suburban fans. Some of the disaffected had taken to sporting hats with the slogan “CMA = Country My Ass.”

Strait, never one to make too big a fuss, saw “Murder on Music Row” as a lighthearted protest. It was never released as a single, but renegade deejays played it enough to nudge it into the top 40. A few months after Strait’s and Jackson’s performance at the ACM Awards, they won the award for Vocal Event of the Year at the CMAs. The song had hit a nerve. It cleaned up in the fan voting at the 2001 TNN/CMT Country Weekly Music Awards, and that fall, Cordle and Shell took Song of the Year honors at the CMA Awards. It was the most popular tune in all of country music, and its unambiguous message was that country music in its current state sucked. As the chorus asserted, Hank Williams, Merle Haggard, and other country legends “wouldn’t have a chance on today’s radio.” And it seems likely that Strait was hinting to the industry that the same might well be true of himself. As a giant of the format, he could safely sing this cri de coeur, but young artists who embraced his classic sensibility were being rejected in 2000 as “too country” for country radio.

It’s unsettling to think of what would happen if Strait, one of the most successful recording artists of all time, in any genre, were to try to break into the business nowadays. Where would he fit in a country scene distinguished (if that’s the word) by the cranked-up party anthems of Jason Aldean, Luke Bryan, and Florida Georgia Line? Is there a “next George Strait” out there, struggling to be heard and make it past the hurdles and hoops of commercial country circa 2014? And if an artist of that ilk and talent did get established, could today’s industry, with its many competing interests, support him over thirty years?

These questions invite a brief review of the music business over the past thirty years. When Strait’s recording career began, in 1981, country radio was loaded with easy-listening pop music, but it still had variety and the capacity to surprise. Strait’s spare honky-tonk was part of a movement the scholars called neo-traditionalism. At that time, the business still retained some of the folkways and institutional memory of its golden age, when historic, multi-decade careers weren’t at all unusual (think of Eddy Arnold, Roy Acuff, or Loretta Lynn). Radio stations and record companies had a special synergy that was largely isolated from the larger media world. That changed about a decade into Strait’s career, when Garth Brooks started filling arenas and selling albums on par with Michael Jackson. A new generation of managers, label executives, music publishers, and lawyers rushed to Nashville and remade the city’s ethos.

Then, in 1996, the Telecommunications Act was passed, lifting the limits on how many radio stations a single company could own. This soon led to “cluster” strategies that assigned specific genres to different stations pursuing target demographics in major markets. Country radio—once a fairly guileless cultural product that appealed to farmers, truckers, and factory workers—became a corporate media machine geared to the tastes and consumption patterns of suburban families, especially moms. Hence the blowup of soft-pop bands like Lonestar, the perky sunshine of SHeDAISY, and the power ballads of Faith Hill.

Yet, at the same time, in contrast to rock and pop radio, which splintered into a dozen or more micro-formats, country radio remained steadfastly cohesive. This limited the labels’ options for breaking new artists with unique sounds and led to radically smaller playlists that featured hit songs more often and over more weeks. The top complaint on Music Row was not that radio was too pop but that it was too slow to add new records. Songs could take nearly a year to reach number one.

And then there’s the money. Old-school payola (i.e., playing a record for cash or gifts) was outlawed years ago. But corporate radio made a market out of the scarcity of slots and access to its shrinking pool of executives who had power over programming. It’s a bit like campaign financing; you don’t pay for a vote—you pay for the chance to make your case. The major labels have always had the deepest pockets, and they dominate the charts. (Industry insiders say that now, by the time a single has reached number one on country radio, its label will have spent at least a million dollars promoting it.)

All of this led to a backlash. In the mid-nineties, disaffected but idealistic label executives and radio people banded together to create a new format and promotion base for artists whose music drew on traditional American sounds and styles, the imperfectly named “alt-country” or “Americana” genre. This category included acts with rock roots like Son Volt and Ryan Adams, as well as exiled forebears like Johnny Cash and Emmylou Harris. Americana has evolved in complicated ways since then, but these days it’s inarguably the more welcoming radio home to neo-traditionalists.

There’s also a parallel ecosystem to Americana: the Red Dirt scene. This is where you’ll find western swing and sawdust shuffles still alive and well. Red Dirt music is regional, centered around Texas and Oklahoma and the Western states. And it’s built on a foundation of live performance and a network of radio stations with their own charts. Well-known practitioners include people like Jamie Richards, a Shawnee, Oklahoma, native who’s landed a dozen top-ten singles on the Texas Music Chart. He’s a “honky-tonk singer with a bit of an edge,” according to his website, and a believer in a “cradle to grave” approach to music. Another example is Aaron Watson, an old-school stylist who’s recorded with Willie Nelson, landed a sponsorship with Tony Lama Boots, and accumulated 250,000 Facebook fans by touring widely as an independent artist.

Impressive as that may be, neither he nor anybody else could become the next George Strait without major-label promotion to mainstream radio. And there, traditional country is scarcer than ever. If there’s a notable exception, it’s Easton Corbin, a 32-year-old native of Florida who came to Nashville in the mid-2000’s. He worked in a hardware store before getting signed to Mercury Nashville, in 2009. He pulled off a feat by reaching number one with his first two singles, and he won three fan-voted American Country Awards in 2010. He’s one of the few guys who has overtly embraced the influence of Strait. His own bio presents him as “the genre’s biggest torchbearer for the neo-traditional movement.”

Others see Blake Shelton as a possible long-haul star. Beloved even after thirteen years on the radio, he’s had eleven number one singles since 2010. And in his role as a charismatic judge on The Voice, he’s found a TV vehicle that’s supporting his success on the radio. He’s got a timeless voice, and his songs won’t sound juvenile on an anthology decades from now. Texas-based radio consultant Pam Shane, of Shane Media, in Houston, says, “Shelton won’t achieve Strait’s prestige, but he has a better chance at longevity than most of the people who have appeared in the last three to four years.”

Brad Paisley, who debuted on national radio in 1999, is the industry’s most outspoken champion for traditional country music, but there are signs that his momentum is slowing. Josh Turner was a hit with critics and on the radio for a while, but he hasn’t been nominated for any big awards since 2008. Women with a classic sound are even scarcer. Miranda Lambert, a Texan, came to town as a devotee of Emmylou Harris’s and has made some quality twangy music. Major-label newcomer Kacey Musgraves, also a Texan, has landed several charting singles and won multiple industry awards, but the adoration of the critics feels like a dark harbinger of how she’ll fare on the radio long-term. I’d love to be proved wrong.

It’s unfair, of course, to ask if anyone can be the next anyone, and one-for-one replacement is not what we want in art and music anyway. George Strait is a once-in-a-lifetime artist from a singular time and place. Were he starting out today, he’d face a quick-hit culture that would undoubtedly clash against his tempo and timing. But then, Strait himself was warning against the creeping hype machine long before “Murder on Music Row.” In the movie Pure Country, he played a star who walked away from the business when the show overtook the substance. Yet at the same recent ACM awards show that honored Strait as Entertainer of the Year, band-of-the-moment Florida Georgia Line rapped over a jet-engine squall, accompanied by flying BMX bikers and more fireballs than a Michael Bay movie. Cognitive dissonance, thy name is country music.

“It’s not a musical agenda. It’s a financial agenda,” says Nashville-based veteran radio promoter Pamela Newman, the president of Crescendo Music Projects. “Now it’s not just about the talent and the song and the record. When you’re an artist going to radio, you’re running for office. You can’t be shy or soft-spoken or simple. If you’re that guy, I don’t think you win the election.”

Or perhaps the system just doesn’t do built-to-last anymore. “Today’s market consists of singles designed for radio airplay on the big stations in major metro areas,” says Shell, the co-writer of “Murder on Music Row.” “The audience never really gets to know an artist and relate in a long-lasting relationship. The record labels used to strive for these twenty-to-thirty-year careers. Now it’s more like eight seconds on a bull named Short Ride.”

Sure, there are some twenty- and thirty-year careers in the making, but by and large you’ll find them in Americana, artists like Marty Stuart, Lucinda Williams, Gillian Welch, and Ricky Skaggs. Many had a turn on country labels at some point, such as Lee Ann Womack, Jon Randall, and Shawn Camp. Some, like Dobro master and paint-peeling singer Randy Kohrs (who looks for all the world like a contemporary country star), are too invested in bluegrass to be relevant to CMA. Some, like the burly, bearded Darrell Scott, earn enough from royalties on now-and-then hit recordings of their songs by bigger artists to make music for their fans that’s in keeping with their own demanding standards.

The music historian in me grieves the banishment of the blues and swing and Red Dirt and bluegrass and all the other traditional forms from country radio. As a fan, I’ve simply redirected my attention, because there’s perhaps never been more crafty, idiosyncratic, fascinating, and beautiful roots music being made. But I can’t look at the homogenization of country music—its forced march from classic genre to narrow-cast format—and not think that the analogy to a crime scene in “Murder on Music Row” rings with truth. I’m there in the crowd, standing behind the yellow tape, craning my neck for a better look, wondering what happened.

- More About:

- Music

- Country Music

- George Strait