My husband likes to say that you can’t walk out your front door in Houston without stumbling over a great story, and I agree. The vibrancy and diversity of life here is almost overwhelming: the daily clash of old and new, of rural and urban (and global), of local and immigrant, and, yes, of very rich and very poor. Even with the wildcatter days behind us, Houston boasts an inordinate number of larger-than-life characters. There’s the boundless creativity of the socially ambitious, the Byzantine folkways of the oil-patch emperors, the international reach of our most ruthless corporate kingpins, the tawdriness of those who control the city’s worst quarters, and so on. Anyone from Charles Dickens to Edith Wharton to Tom Wolfe would have or should have killed for the chance to take Houston on.

And yet, so far, few have stepped up. The hands-down best novelist on Houston is Larry McMurtry; the best of his books set here—Moving On, All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers, Terms of Endearment, and The Evening Star—evoke the place with affection and authority. But McMurtry’s last Houston book came out in 1992. The city makes fleeting appearances in some excellent short stories by Antonya Nelson, who teaches in the University of Houston writers’ program, and in some well-drawn scenes in Rice professor Justin Cronin’s popular vampire series, the Passage Trilogy. Alicia Erian’s underappreciated novel of the southwestern suburbs, Towelhead, also bears mention, as does the work of Attica Locke, whose thrillers have introduced countless readers to a heretofore unknown Houston. But when compared with the reams of stories set in New York, Los Angeles, or even the Metroplex—Semi-Tough, Strange Peaches, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk—the output looks paltry, especially given the richness of the potential subject matter.

Yes, there are challenges to writing about Houston. It’s not a city that most Americans are familiar with. As Cronin pointed out to me, “When you write about Houston, you get no freebies.” Other cities have obvious signposts: the year-round sunlight in Los Angeles, the misty fog of London, the blaring taxi horns of Manhattan. Throw in a few familiar atmospherics and you’ve nailed a place before the reader has gotten through the first few pages. But with Houston, every writer is pretty much starting from scratch.

Houston is also a relatively young city. “In terms of history there’s oil and NASA,” Cronin said. “So writers fall back on easy stereotypes.” For a local reader who wants to see his or her home reflected in an enlightening way, that’s no fun. A novel is by definition a work of fiction, but when a writer gets too many facts wrong—azaleas blooming in July, for example—a knowledgeable reader’s distraction turns to distrust and, finally, dismay.

Still, there’s room for hope. Three new novels set in Houston—Anton DiSclafani’s The After Party (Riverhead Books), Melissa Ginsburg’s Sunset City (Ecco), and Yvonne Georgina Puig’s A Wife of Noble Character (Henry Holt & Co.)—suggest that the city may finally be having its literary moment. On their own terms, the books make for entertaining summer reading, especially for women. In fact, all three are oddly similar in their feminine concerns: they all feature women who suffer because of their sexuality, who are engaged in conflicted friendships with other women, who are steeped in the toxic stew created by the mixture of large amounts of cash and parental love (or the lack thereof), and who are financially challenged yet closely involved with members of Houston’s moneyed class. And all three books are similar in one other manner: they hit and miss when it comes to getting Houston right.

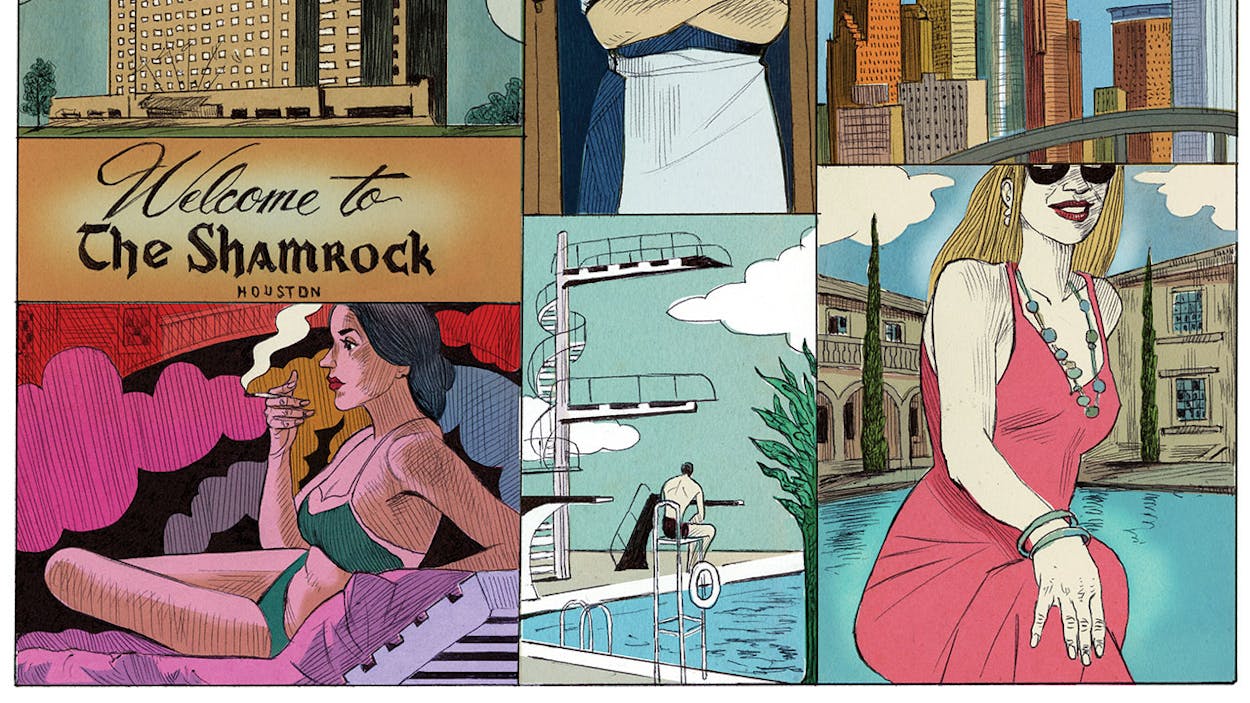

The After Party is set at the dawn of what could be considered Houston’s first golden age, that time in the late fifties between the heyday of the Shamrock Hotel and the completion of the Astrodome. Houston was more than two decades away from the explosive growth that would turn it into a global city, and most of its rich folk were still insular and provincial (no oil sheikhs on the scene).

The plot involves the fate of the mysterious Joan Fortier, a young woman from a wealthy River Oaks family, and her best friend, Cece Beirne, who is both envious and protective of the self-destructive Joan. It’s an accomplished, twisted story of family secrets—but one that could just as easily have been set in Greenwich, Connecticut, or New York’s Upper East Side. DiSclafani, who spent summers in Houston as a child and now teaches in Alabama (her previous novel, The Yonahlossee Riding Camp for Girls, was a best-seller), must have had a blast doing her homework, poring through news clippings and interviewing people who still recall those days, which for the rich were occasionally untethered when it came to rules of behavior.

Her research shows—the characters dine and dance at all the right places—but I longed for a truer evocation of place. The reader goes to the Cork Club and Maxim’s but never gets a sense of what either venue looked or felt like, so these iconic places don’t get their eccentric due. (“Later tonight we might venture outside, to the Shamrock’s pool, which happened to be the biggest outdoor pool in the world, built to accommodate waterskiing exhibitions,” DiSclafani writes, in a passage that does the work of a Wikipedia entry but never quite lands us in the water.)

The same is true of Joan, an upper-class vagabond who walks across grass barefoot—the sort of thing most Texas children, after their first encounter with fire ants and sticker burs, learn early not to do. DiSclafani tells us that Joan “made people happy” and was “lit from the inside,” but the charisma of that kind of Texas woman—the humor, the fearless sexiness, the life force—is never quite there. Despite being daring and bold, Joan just isn’t that much fun to be around, in contrast to so many Houston women, everyone from socialites like Joan Hill or Lynn Wyatt or Joanne Herring to the waitress at my favorite barbecue joint. I longed to hear this Joan crack a joke—to sum up a scene with a flawless, deadpan assessment—but by the end of the book I was still waiting.

Like The After Party, Ginsburg’s Sunset City boasts a compelling plot, rife with long-held secrets and surprising twists. In this case Danielle Reeves, the daughter of a wealthy River Oaks divorcée (yes, we’re back in River Oaks), is murdered, and her semi-estranged oldest friend, Charlotte Ford, a barista whose life is on hold, goes looking for answers. Because Danielle slid from wealth into a world of drugs and porn, Charlotte has the opportunity to take the reader into some of Houston’s bleakest precincts.

Ginsburg, who lives and teaches in Mississippi, was born and raised in Houston, which gives her an advantage over DiSclafani. She displays an authoritative hand with the seediness of certain Montrose corners, the regional cuisine (“I ordered a baked potato filled with butter and sour cream and bacon and slow-smoked brisket”), and the weather (“Houston was always flooding, the whole city built atop paved wetlands”). It’s fun to feel the properly oppressive air-conditioning in the gleaming office of Danielle’s mother, a real estate developer; as in the other two books, we spend a lot of hot, humid days by the pool, either smoking weed or drinking, which seems just right for this particular demimonde.

What’s missing from Sunset City is the very real darkness of darkest Houston. Anyone who recalls the last section of Tommy Thompson’s classic 1976 true-crime book, Blood and Money, knows that things have only gotten worse since the seventies: the neighborhoods with armed teenage lookouts in front of shooting galleries, the brothel-infested strip malls (Thai massage, anyone?), the hollow-cheeked addicts with their cardboard signs near freeway on-ramps, the well-off trust fund brats who think they can slum without cost. For a self-declared “taut, erotically charged literary noir,” Sunset City shies away from taking a truly penetrating look at a city that is both a gun mecca and a national center of sex trafficking. That side of Houston isn’t pretty, but it’s as luridly seductive as what goes down in River Oaks.

A Wife of Noble Character, unlike the other two books, possesses something that is intrinsically Houstonian: a sense of humor. Puig has written a novel of manners, nervily modeled on Wharton’s The House of Mirth but set in modern-day Houston. Like Ginsburg, Puig was born and raised here, though she too fled the scene; she now makes her home in Santa Monica. Apparently, no matter how far you move, Houston sticks with you; Puig has the local milieu down cold.

Her heroine, Vivienne Cally, is a thirty-year-old woman whose family name is bigger than her bank account and who keeps trying, almost against her will, to find a husband among the Houston rich she grew up with. Puig has a great eye for the enforced conformity of this social class. Early in the novel, Vivienne envisions her future with her thick-headed boyfriend, the appropriately named Bucky Lawland: “Church at Prayerwood every Sunday, followed by brunch with the other wives. Tennis three days a week. Autumn tailgating parties in Austin and Dallas, umber leaves scattered on the pavement among rows and rows of tires and barbecue pits. Christmas in the Cayman Islands. March skiing in Vail. A ranch of her own.” Alas, this is not to be, after Vivienne makes an overly enthusiastic (for her crowd) sexual error and is more or less cast out of paradise.

Puig’s ear for dialogue is unassailable. In one scene a girlfriend extends an invitation in the local patois: “It’ll be SO FUN!” In another, when Vivienne arrives at a friend’s ranch for an engagement party, the obligatory Latina housekeeper relays the hostess’s request for assistance in flawless Spanglish: “Necesita ayuda con la wedding.” Then there’s a true-to-life, grimly funny argument over the morality of hunting (Vivienne: “We don’t know if God put animals on earth just for us to kill for sport.” Bucky: “You gonna disagree with Scripture?”). These throwaway lines aren’t just good writing—their vernacular acuity locks the reader, especially a Houston reader, into a particular place and time. Puig lets everyone feel at home, including those of us who live here.

Her only misstep—spoiler alert—is to tack on a happy ending that seems awfully pat. In the last few pages, Vivienne gets pretty much everything she wants and suffers no repercussions for any of it. In Houston, though, it’s the rare society-born bird who can escape the confines of her well-appointed cage without serious consequences. In the end, Edith Wharton might have understood Houston’s rich better than Puig does.

But still. The mere existence of three new novels that try to capture something about this underestimated city is cause for celebration, even if they’re not completely successful at it. Yet I’m still waiting for the kind of sprawling, Dickensian novel that includes Middle Eastern valets, Vietnamese arbiters, Latino lawyers, and, yes, craven River Oaks socialites. And a black mayor conferring with his lesbian predecessor for good measure.

I don’t know, maybe you just can’t make this stuff up.