Abbie Hillis had never seen clear high heels before her coach, Barry Hyder, asked her to try on a pair. He’d brought the shoes to the branch of the Austin-area Capital Gymnastics chain where Hillis trained. It was, she thinks, probably 2002, though she’s not certain. She would have been about twelve years old.

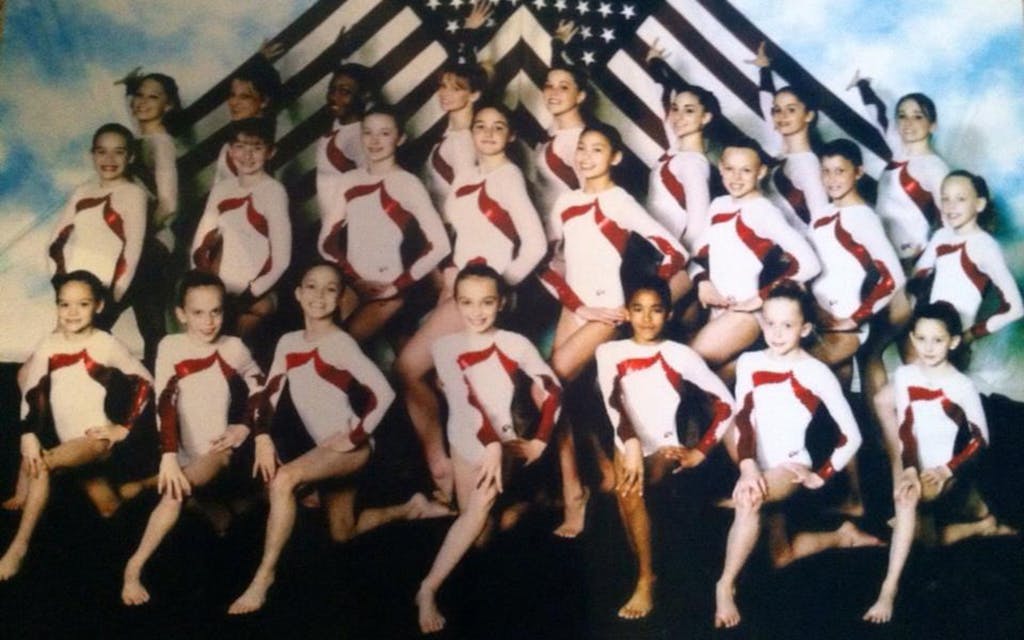

She’d joined the gym when she was five, and within a few years, she was conditioned to do whatever her coaches asked. She was an athlete training to compete at a high level, and that meant saying no came with consequences. She’d once been suspended from practice for a week for refusing to perform a front walkover on the balance beam, a maneuver she hadn’t yet learned. A coach yelled at her for going to the bathroom when she got her first period. So, Hillis says, when Hyder showed up with a bag of lace tank tops and miniskirts and told her and the girls she trained with that they’d be holding a “fashion show,” she complied—even though “my body knew that it was wrong.”

“We had this weird feeling,” Hillis says of the group’s reaction. “Like, ‘This is not right,’ but also ‘This is a man we trust.’ ” She remembers giggling with the other girls. “The environment is so intense that when a funny moment happens, it’s almost a relief, like, ‘Oh, we get thirty minutes of not having to do bars today.’ ”

A woman we’ll call Ann Williams (she requested her name be withheld) trained under Hyder at the same, now-shuttered Capital Gymnastics location in the early aughts. She also remembers the fashion show, though she too says she’s unsure exactly when it happened. Hyder told her she was “too big” to fit into the clothing, she says, so she had to sit and watch. “It was extremely awkward for the girls he made wear the clothes,” she recalls. Hyder did not respond to multiple interview requests from Texas Monthly.

According to seven women Hyder coached between 1981 and 2019, the incident fit a pattern of inappropriate behavior. Hillis says Hyder often blurred the boundaries between his personal life and his coaching. The girls, she says, heard all about his dating life, his 2004 divorce from a former student he’d married, and his workout routine for maintaining a “hot bod.”

Complaints about Hyder’s conduct stretch back to his early days as a coach. Amy Duval, who trained with Hyder at Dallas-area gyms in the early eighties, says he began flirting with her when she was fifteen and he was in his mid-twenties. She says he would ask her “what girls at my school did with boys.” The questions made her uncomfortable, but because Hyder was her coach, she trusted him. When he left that gym, she followed him to his new position at another in North Texas.

The behavior escalated, she says. Shortly before Duval’s sixteenth birthday, Hyder got her parents’ permission to take her to Houston for a competition and a chance to train with famed gymnastics instructor Béla Károlyi (who would later face accusations from gymnasts of physical and mental abuse and of tolerating sexual abuse by others). During the trip, Hyder visited Duval’s room and gave her a massage during which his hands were “all over” her body, she says, and ended the session with a kiss on the lips. On the drive back, she says, she pretended to sleep while he put his hand inside her bra. A few weeks later, she says, he had sex with her for the first time. (Duval was under the age of consent in Texas, which was and remains seventeen.) “He stole my virginity with zero discussion,” she says. She continued training as an Olympic-level gymnast and earned a full athletic scholarship to Louisiana State University, but she left school and the sport at Hyder’s urging, she says. The two married in 1986, when Duval was nineteen.

J. J. Conley, who also trained with Hyder in North Texas, says she had her first sip of alcohol with the coach during a team trip to Germany in 1989. She was sixteen. She remembers drinking her first beer, then taking a cab back to the hotel with him. “That was the first time he kissed me,” she says. He continued kissing her, she says, after they returned to Texas, in the gym and even at her house, when Conley’s mother hired Hyder to repair some drywall. He stopped, she says, after she started dating a boy her age.

In 1991, when Hyder began working at Capital Gymnastics, Hyder and Duval moved to Austin. The couple divorced in 2004, but Hyder would continue coaching at Capital until 2019.

Sierra Hill, who was eleven when she started training with Hyder in 2009, remembers the coach making inappropriate comments. “He would always point out people’s boobs,” she says. “He would talk about if you’re underdeveloped, overdeveloped, have you get on the trampoline, jump up and down, watch you. He would joke about how I was a lot more underdeveloped than some other girls. When I did start developing, he was like, ‘Finally. You’re fourteen.’ ”

Tara Vaughn (also a pseudonym; Vaughn is a minor) first met Hyder in June 2019, when she was twelve. Hyder trained her while substituting for a coach at the Capital Gymnastics location in Round Rock. Her mother, who had followed the highly publicized culture of sexual abuse in gymnastics, instructed Vaughn to tell an adult if one of her coaches ever touched her inappropriately. In Vaughn’s first session with Hyder, she says, he pressed his hand against her buttocks while she attempted a maneuver on the high bar; later that day, he put his hand on her chest during a trampoline exercise.

After practice, she and another gymnast with a similar complaint told their parents and their regular coach what had happened. The next morning, the parents received an email from that coach requesting a meeting to explain “how the situation has been handled.” The parents say they left the meeting with the understanding that the gym’s owners, Jim and Cheryl Jarrett, had reviewed surveillance video and vowed that Hyder would never work at another Capital Gymnastics location.

Jim says the gymnasts and their parents “misinterpreted [Hyder’s] style of coaching” and that he does not believe that the complaint indicated the coach engaged in sexually inappropriate behavior. Jason Jarrett, the couple’s son and chief of operations at Capital, says management received a complaint related to Hyder’s actions but that the coach who relayed the complaint did not specify the nature of the incident as sexual. According to the Jarretts, Hyder was considering stepping away from coaching at that time for other reasons, and the four of them mutually agreed to move him into other roles. Jim says Hyder worked two more shifts at Capital’s Cedar Park gym, doing janitorial tasks and equipment maintenance, before leaving the gym altogether. Soon thereafter, he left Texas entirely.

After learning that other gymnasts had had similar experiences with Hyder, Vaughn’s mother decided in 2020 to file a complaint with the Round Rock Police Department, which investigated the case. But according to the police report, the Williamson County district attorney’s office did not pursue charges. (The office declined to explain why, telling Texas Monthly that as a matter of policy, it does not discuss cases that don’t go to prosecution, especially those involving children.) After Hyder left Texas, he began coaching at another gymnastics facility, in Bentonville, Arkansas, for part of 2020. He no longer works there, according to the gym’s owner, who confirmed that Hyder was employed there for a time but offered no further comment.

All of the women who spoke to TM about Hyder recall feeling uncomfortable about the way he touched them. Together, their accounts reveal a pattern: Hyder would begin with unsolicited shoulder and leg massages when the gymnasts were preteens. As they grew older, his behavior would escalate to squeezing their buttocks or cupping their breasts when spotting them. His conduct was unlike that of other coaches, who would, when necessary, point at or tap those areas of the body during training. “I’ve coached, so I understand that hand slippage happens,” says Hillis, who’s now 31. “But you’re trained on how to handle it when an inappropriate thing happens, and his hand went into a place that it definitely shouldn’t have. And it was never talked about.”

Hillis has spent several years organizing sexual-assault survivors. In 2018 she formed a group at Texas A&M University called Twelfth Woman, which successfully lobbied the school to improve its policies regarding sexual assault and harassment. She also began talking with other gymnasts who trained under Hyder and eventually released those conversations as a podcast. In July 2020, she filed a report with USA Gymnastics (USAG), the sport’s national governing body. Because the complaint contained allegations of sexual abuse, it was forwarded to the U.S. Center for SafeSport, the congressionally mandated oversight agency for Olympic athletics.

Investigators for SafeSport have since interviewed at least nineteen gymnasts who’ve made allegations of sexual misconduct against Hyder spanning the almost forty years he spent coaching in Texas. But nearly two years after Hillis filed her report, SafeSport has yet to conclude its investigation, leaving the women in a state of limbo that has sown distrust of the very agency that is supposed to protect them.

The dark side of gymnastics has been one of the most discussed issues in sports in recent years. Last May, the Australian Human Rights Commission released a report describing gymnastics in that country as a “high-risk environment for abuse.” In 2020 gymnasts worldwide took to social media, using the hashtag #GymnastAlliance, to describe their experiences with physical and emotional abuse—many of them speaking out for the first time. Of course, criticism of misbehavior in the sport isn’t new. In her 1995 book Little Girls in Pretty Boxes, journalist Joan Ryan described gymnastics as “legal, even celebrated, child abuse.”

Because of the age at which gymnasts begin training for the highest level of competition, they are particularly vulnerable. Conley, Hill, Hillis, and Williams all entered the sport as children and reached Level 10, the highest pre-Olympic designation. Williams, for example, started at Capital when she was two years old with mommy-and-me tumbling lessons. Training through injuries and attempting maneuvers against a doctor’s advice are common in the sport. That culture, the women say, also helps explain gymnasts’ reluctance to report abuse. “You just learn to not know how to trust yourself with anything,” Hill says. “It’s a common gymnastics thing. If you push through pain, you’re considered tough and you’re better than everyone else.”

That tension was also part of the culture at Capital Gymnastics, according to several of the gymnasts who spoke with Texas Monthly. They blame Hyder for his behavior, but they also say the gym’s owners, the Jarretts, created an environment in which girls did not feel they would be believed if they came forward with their concerns. “I didn’t complain to anybody about Barry,” Williams says, “but I did complain and report to my parents about other [verbally abusive] coaches, and my mom brought those coaches up to the Jarretts. In those situations, things didn’t change.” Hill says she, too, believes that the culture of the gym made it so that the Jarretts would have been unreceptive to complaints. “They’d probably believe Hyder instead,” she says.

All of the women who spoke to TM about Hyder recall feeling uncomfortable about the way he touched them. Together, their accounts reveal a pattern.

Jim Jarrett acknowledges that the athletes are justified in their concerns. “There are some obvious reasons why anybody would feel uncomfortable coming forward,” he says. “For sure—they’re justified because it’s their interpretation.” He takes issue, however, with the accounts of alleged abuse at Capital Gymnastics. He says the gymnasts “were never in harm’s way” and that if they felt they had been touched inappropriately, “we would have known about it, and we would have received a complaint about it.” He believes that the gymnasts have an “interpretation” of Hyder’s behavior that is “inaccurate” and that the “fashion show”—an event he did not witness—didn’t occur the way that the gymnasts who were involved allege it did. Jason Jarrett says his initial understanding of the incident involved the gymnasts seeing the bag of clothes in the trunk of Hyder’s car and the coach making a joke about the girls trying them on. Jason claims he did not hear that Hillis and the other gymnasts had worn the clothes in the gym until years later.

Hillis says she went to the Jarretts’ Round Rock home and told them about Hyder’s behavior sometime around 2016. Sitting in their house, she says, she recounted the unwanted massages, the inappropriate touching, the fashion show, and the sexual comments about gymnasts’ bodies. Jim remembers Hillis’s visit and her complaints about Hyder, but he says she never mentioned any inappropriate touching.

When Hillis reported Hyder to SafeSport, however, she described that meeting with the Jarretts, naming them in her complaint for what she considered inaction. “I have reported the abuse [by] . . . Barry to these owners and they have neglected to do anything to report the abuse to law enforcement or USA Gymnastics,” she wrote. “I spent hours at their house telling them everything listed in this report, and they thanked me for coming forward.” Hyder continued to work at Capital Gymnastics until 2019.

Amy Duval met the Jarretts when she was fifteen; Cheryl was one of her first coaches at the Dallas-area gym where she met Hyder. After Duval turned nineteen and married Hyder, she would encounter the Jarretts at competitions in her role as Hyder’s wife. Duval believes the Jarretts should have seen Hyder’s marriage to a former student as a red flag. “I wouldn’t want to hire a coach who had married his gymnast,” she says. “And if you did, wouldn’t you become suspicious at any hint of abuse? They kept him. Why?”

“We knew that she was a gymnast at one time that he coached,” Jim says, but “I would assume that, because I met Amy in this transition of him from up there [Dallas] to down here [Austin], that it was all on the up-and-up.

“On my watch as a gymnastics-school owner for over forty years, I just say I’m sorry,” Jarrett says. “I don’t want [anybody] to be saddened by somebody in my employ that you feel you’ve been wronged by. That’s not what we’re about. They need to hear that. Some of the interpretations of what occurred at the time, in which they seem to think that something was done wrong—that in many ways was not told to me, which would have been addressed. And some of it is just inaccurate.”

In 2016 the scandal around sexual abuse committed by former U.S. national team doctor Larry Nassar brought new scrutiny to the sport. In response, USAG strengthened its protocols for responding to allegations of abuse. Congress granted the U.S. Center for SafeSport exclusive jurisdiction over allegations of sexual misconduct across all Olympic sports.

On paper, the policies put in place at USAG and SafeSport are impressive. A December 2020 report from the Government Accountability Office noted that 63 percent of cases resolved by SafeSport were closed in one to three months. According to the Wall Street Journal, SafeSport, which has a hundred employees, expected that more than three thousand reports of abuse would be brought before the organization in 2021. Although some cases have taken SafeSport a year or more to investigate, Dan Hill, a crisis public relations expert who serves as a spokesperson for the organization, says, “That was more common in the beginning, when we had a backlog and had to administer triage.” He concedes that in SafeSport’s early days, it struggled to keep up with the numerous complaints. “We’re not defensive about this,” he says. “The center started understaffed and under-resourced, and it got flooded with complaints.” It continues to receive many complaints, he adds, but the staff has “grown dramatically.”

Still, some inquiries continue to drag on. A 2016 allegation from a gym in North Carolina that predates SafeSport’s formation remains unresolved. The organization took more than a year and a half to interview coaches from an Illinois gym involved in a case that was sent to SafeSport in August 2019. In September 2021, speaking before the U.S. Senate, retired Olympic gold medalist Aly Raisman described SafeSport’s approach to complaints as “playing hot potato, where someone . . . kicks it over to somebody else and they don’t hear back for a really long time.”

The Hyder investigation, which began in July 2020, has been ongoing for 21 months.

Dan Hill says he can neither comment on the specifics of an ongoing case nor confirm the identities of individual SafeSport investigators. The women who reported Hyder believed the case was close to a resolution in November 2020, when the first investigator assigned to the case completed his interviews with the claimants. That month, however, SafeSport replaced him with another investigator, who restarted the process from scratch.

“All of a sudden, without any explanation, [the first investigator] just couldn’t be contacted anymore, and we couldn’t get ahold of anybody from SafeSport,” says Michaela Sousares, one of the gymnasts who reported Hyder for sexual misconduct. She says it took “months and months and months” to hear from SafeSport. During that period, the gymnasts noticed headlines about a data breach at SafeSport and worried that video and audio recordings of their interviews might have been exposed.

According to Hill, the hack targeted a vendor that SafeSport works with, and no data regarding investigations was compromised. But at the time, the organization failed to explain what had happened or reassure the women that their personal information remained secure. When the women contacted SafeSport for information, Sousares says, the center’s employees were evasive. “They wouldn’t answer any of our questions,” she says. “And then, all of a sudden, they gave us a new case investigator.”

Hill says “it’s possible” that the women had to wait months to get word from the organization. “If that happened, that’s something the center would want to do better.”

All of the women Texas Monthly spoke with who had been interviewed by the initial investigator spoke highly of him. Their impression of his replacement was less positive. The second investigator asked the gymnasts to recount, once again, their experiences with Hyder. None of them understood why they had to go through the process a second time.

Catherine Carroll, a former Title IX officer at the University of Maryland and cofounder of the Sexual Violence Law Center, tells TM that an investigation can be thorough without asking claimants questions they’ve already answered. “The whole point when you interview a victim is to try to minimize the number of times you’re going to ask them those hard questions,” she says. “I can’t think of any justification for why you would need to do a whole new interview starting from scratch, unless everything was destroyed.” Dan Hill, citing SafeSport’s policy against discussing details of specific cases, declined to explain what prompted SafeSport to restart the inquiry.

Hillis and the other women who reported Hyder have other concerns about the investigation. They cite what they see as a lack of transparency on the part of USAG regarding its relationship with the Jarretts and express doubts that USAG is taking seriously their allegations against the couple. At the time the gymnasts filed their complaints, Cheryl Jarrett, Hyder’s former boss, was employed as a consultant for USAG, where she had previously served as vice president of member services from 2011 to 2018. Shortly after SafeSport began looking into Hyder’s case, in the summer of 2020, Jim Jarrett informed Hillis in an email that USAG had terminated Cheryl’s contracts and employment. “Cheryl and I have been asked to step away from any responsibilities associated with USA Gymnastics,” he wrote. “I can only assume that this has something to do with Barry.” In a July 2021 email, however, Jim confirmed to TM that USAG had rehired Cheryl the previous January.

Hillis says this lack of clarity further eroded her trust in USAG. When she asked directly whether Cheryl had resumed working for the organization, a USAG official replied to say that the institution “could neither confirm nor deny” Cheryl’s role. The organization declined to answer the same question from TM, citing “respect for individuals’ privacy.”

The gymnasts were also frustrated by the opaque web of bureaucracy between USAG and SafeSport, which makes it difficult to discern where one organization ends and the other begins. USAG employs both a “director of safe sport education and training” and a “safe sport administrative manager.” According to several of Hyder’s accusers, such overlapping titles have left them wondering who is ultimately responsible for the investigation. “So, it’s confusing, and we’ll be the first to admit it,” says Dan Hill. “It’s something we’re working on.”

When the initial complaint against him landed at SafeSport, Hyder was placed on a list that allowed him to continue coaching minors in the presence of another adult coach. In November 2020, nearly five months later, SafeSport suspended him from all coaching activities. The following January, Hyder withdrew a request to appeal that suspension, meaning he will remain sidelined until the investigation’s conclusion—assuming it ever reaches one.

The gymnasts had initially hoped that SafeSport would provide some form of closure and justice. Instead, they say, they’ve lost confidence in the process. Hillis says she’s exhausted from fighting and worries about coming off as a victim. “I want to be the hero of my story, the one who organized these women around this and pushed to make a change,” she says. “I’m tired of being seen as poor Abbie with her sad story.”

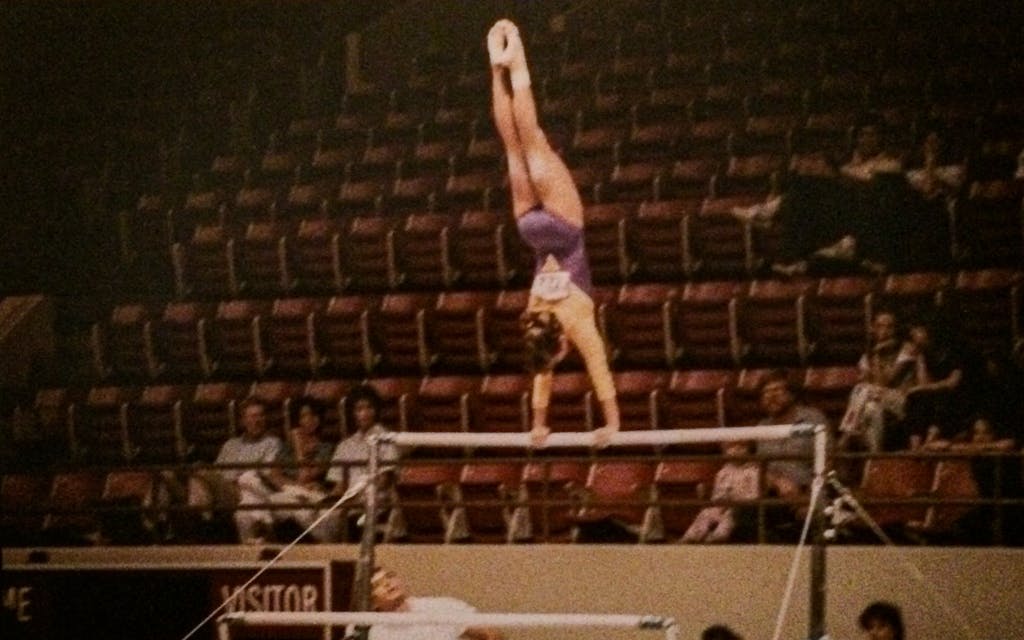

That’s a recurring theme with the gymnasts who reported Hyder. They’re proud of their accomplishments, proud of the people the sport helped them become. Duval, who was married to Hyder for eighteen years, emphasizes that she wants people to know she wasn’t just a woman who came forward about his abuse but also that she was an outstanding gymnast who earned a full athletic scholarship to a highly competitive SEC university.

Today the women receive regular emails from the new investigator reporting that “the case is progressing, and I am getting close to concluding the necessary interviews for my investigation.” But the updates contain few details.

Meanwhile, awareness of the problems within the sport continues to grow. In December 2021, USAG finalized its settlement with more than five hundred gymnasts who submitted abuse claims related to the actions of coaches, trainers, doctors, and other figures associated with the organization. Many of those athletes had lodged allegations specifically against Larry Nassar, but hundreds of them had no experience with the Michigan-based physician, who pleaded guilty to multiple counts of first-degree criminal sexual conduct with minors.

Tara Vaughn is the youngest gymnast Texas Monthly spoke with. She was twelve when she told her mom that Hyder touched her—a few years younger than Duval was when she met Hyder. Vaughn is fifteen now and still a gymnast, though these days she trains at a different gym. Her favorite routines are floor and vault. Launching herself into the air can be scary, she says, but she has a trick: “It sounds kind of funny, but I think about my favorite food to distract my mind.” She’s in ninth grade, and she’d like to compete for her high school team. At this point, she’s still able to think of gymnastics as a safe place.

When Duval thinks about Vaughn—who’s younger than Duval’s own

children—and other girls growing up in today’s gymnastics culture, where the subject of abuse is more widely discussed, she feels conflicted. On the one hand, she sees how gymnasts are growing up with a better understanding of what’s appropriate, what’s abusive, and how to protect themselves from behavior that crosses the line. On the other hand, she’s heartbroken. “This may sound selfish,” she says, “but where was that for me?”

This article appeared in the April 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Unsafe Sport.” It originally published online on January 20, 2022. Subscribe today.