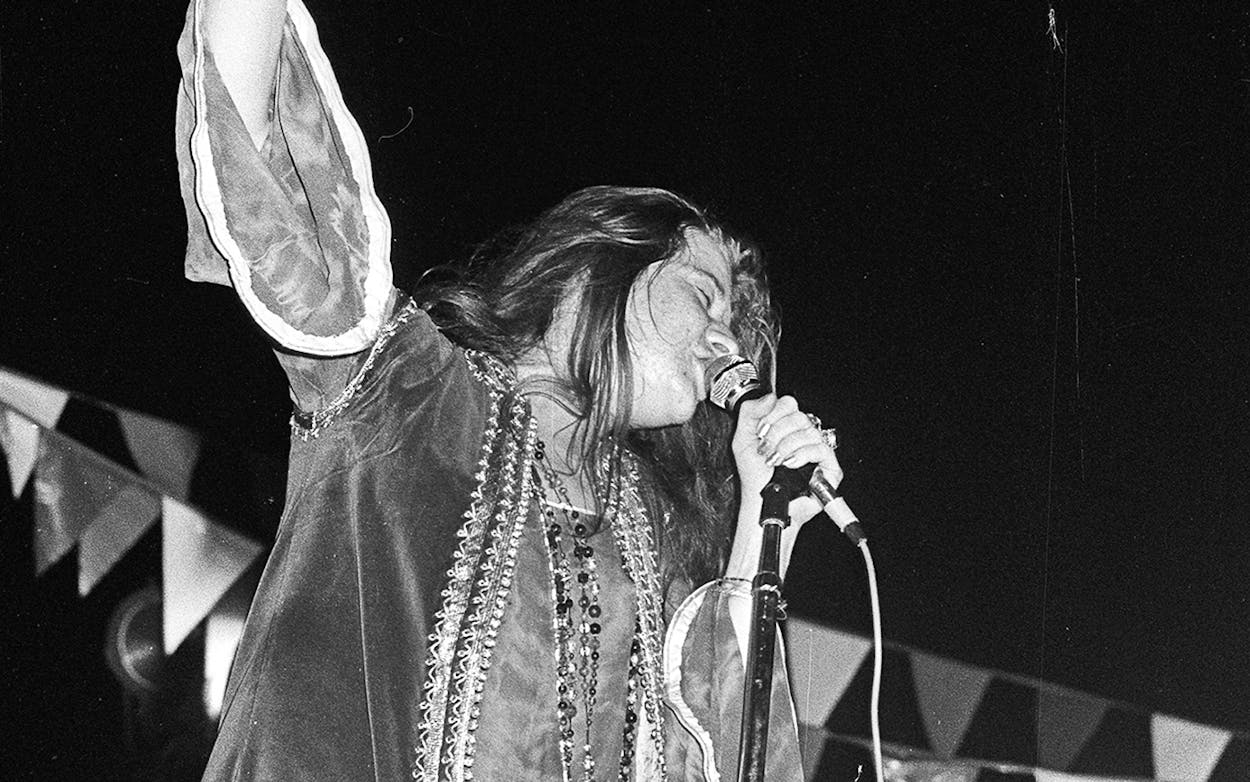

In 1969, Janell Myers grew her hair long to protest both the preferences of her cosmetology-teacher parents and the war in Vietnam. Being a fifteen-year-old with anti-corporate views in Richardson, Texas, could get lonely. She had Janis Joplin, though, and the solace of “Little Girl Blue.” Many versions of the popular song had come before and would come after. Joplin’s take, sung with knowing pain and reassurance, reached Janell at the right time.

So did Woodstock. As Janell recounted years later for a University of North Texas oral history project, it took a full day before she heard about the astonishing crowds who had filled a six-hundred-acre dairy farm in New York to love music and each other. They were people who, like Janell, relished Joplin’s unbound, transgressive joy and moody guitar, made their own clothing in bold fabrics, and seemed free.

Joplin’s Woodstock set seemed so frustratingly far away, already history. But then Janell learned that the Port Arthur-born singer—and Sly and the Family Stone! and Led Zeppelin!—were coming to Lewisville, then a “cowboy town” in North Texas, just two weeks later on Labor Day weekend. A poster for the Texas International Pop Festival promised twenty bands and “free camping.” Janell used her mother’s credit card to buy a ticket.

She and her older brother promised their parents they’d return home each night after the last set. They didn’t. Once Janell made it to the Dallas International Motor Speedway, the site of the festival, she promptly found a spot near the stage. For the first time in her life, she saw nothing but people as far as her eyes could track.

The Texas International Pop Festival is typically remembered every ten years or so in the North Texas press as a Woodstock spillover. The host city likes to refer to it as “Lewisville’s Own Version of Woodstock,” especially this year, the fiftieth anniversary of both festivals and the occasion for a lower-key restaging this Saturday and Sunday. The band Chicago (known in 1969 as Chicago Transit Authority) returns to headline with ZZ Top. The venue this time is Lake Park Golf Course, about eight miles from the field where the racetrack used to be.

That summer of 1969, Chicago’s management had actually turned down an offer to play Woodstock. The band’s trumpet player, Lee Loughnane, remembers that they opted instead to play a show at Fillmore West, the legendary venue in San Francisco, where they’d make better money. The hippie festival in New York wasn’t offering commission.

As significant as it was for a little town like Lewisville, for the members of Chicago, the Texas International Pop Festival was just another gig on a marathon tour. (They’re still on the road, fifty years later.) “As a musician and a hippie, we thought that getting high was the way to perform music, so we were high before we played and after we played,” Loughnane told me. “The most interesting thing now, the reason we get to do this today, is because we stopped.”

Despite any parallels to Woodstock, the Texas International Pop Festival was more of an heir to the Atlanta International Pop Festival, which took place that same summer. Angus Wynne III, son of Six Flags developer Angus G. Wynne, told me that he’d attended that Fourth of July weekend party and was young enough, at 25, to believe he could pull off one like it in North Texas. He teamed up with the Atlanta festival’s organizer, Alex Cooley, and the duo rush-booked the Lewisville event.

In addition to Joplin and Zeppelin, B.B. King, Santana, Herbie Mann, Johnny Winter, and Canned Heat were on the powerhouse bill. Todd Rundgren’s rock band Nazz played Pop Fest before a residency at beloved Dallas club the End of Cole Avenue. Grand Funk Railroad, not yet a major band, played a free stage along the lakeshore. Instead of the rain that turned the Woodstock dairy farm into fields of sludge, festivalgoers in Lewisville crisped in the full late-summer sun on blankets, waiting for pot or LSD to appear as it was passed around freely.

Pop Fest’s best-documented distinction, though, is the fraught relationship between the late sixties counterculture and Lewisville, then a town of just eight thousand residents. This clash is best represented in widely reported and photographed scenes of skinny dippers frolicking in the lake while boats filled with townspeople (mostly men) pulled up to watch. Later a flyer distributed to take Pop Fest’s organizers to task for indecency called them “smut peddlers” and “moral thieves.” The planning had gone too fast, though, for mayor Sam Houston to shut the whole thing down.

It also perhaps had gone too fast to meet Angus Wynne’s expectations. Roughly 100,000 spectators turned out for Pop Fest, but that was only half what Wynne had anticipated. He ended up $100,000 in the hole.

By most accounts, there was much more kindness than trouble among the crowds. Folks from the influential commune Hog Farm, who’d set up a free kitchen at Woodstock and helped keep order, served three thousand fried chickens provided by the Minnie Pearl restaurant chain. Watermelons appeared from seemingly nowhere, to the delight of concertgoers who scooped chunks out with their hands and passed them on.

Generosity also came from less-expected places. Lewisville police chief Ralph Adams, who’d submitted his resignation a few days before the festival, ran security on Pop Fest’s payroll. At the end of the weekend, he held up a peace sign and told the crowd, “You are fine … You are welcome back here anytime you want to. The town is yours.”

Adams endured a grilling by members of local media during his last few official days on the job. WFAA-TV reporter Murphy Martin asked him if he was sorry for seeming friendly to narcotics with minimal arrests and no show of force.

“Murphy, I am not,” Adams said. “I would have handled it this very same way.”

Of all the eyewitness accounts surfacing for the fiftieth anniversary of Texas Pop Fest, one seems particularly complete. Prolific Dallas folk singer Lu Mitchell wrote “Lewd and Loose in Lewisville” within a week after the festival. Her son Sean remembers playing the song live with her at a Dallas coffee shop—which one, he can’t recall when I ask him. But he knows he called out the Dallas Morning News about the rant of an editorial that lent the song its title and said he hoped the folks at the paper could hear the song from their office on Young Street downtown:

We were lewd and loose in Lewisville, we had us a time

Lewd and loose in Lewisville covered with dirt and grime…

Lewd and loose in Lewisville

The Dallas News told you so.

Matthew Long’s first task in assembling an exhibition in honor of the festival was to crop one of those skinny-dipper photos to make it “decent for families.” At first those images were all that the curator of exhibits for the Denton County Office of History and Culture had for the fiftieth anniversary show. They’d arrived in a packet of ephemera from Murphy Martin’s widow.

But soon Long and his fellow curators enlisted the help of Richard Hayner, who spearheaded the push for a historical marker near the former racetrack site in 2010 and runs a Facebook group where people reminisce about the festival. The result of their search for ephemera is a collection, on view through September 28 at UNT on the Square in Denton, of original posters, photography, the program, a mock concertgoer’s tent for visitors to climb into, and a Fender Telecaster in a glass case. (“It’s the same make and model as the one played by Sly Stone,” Long told me, “not the actual guitar.”) A version of the exhibit opens Saturday in Lewisville at the MCL Grand Theater and will run through October 19.

“The townspeople of Lewisville were completely overwhelmed,” reads one anonymous account on display at the Denton gallery. “They just stared, slack-jawed. For us, walking through town was surreal. I remember we were trying to buy some food items at a supermarket, like Safeway or something, but the shelves were practically bare.”

Next to that story is a photograph of a shirtless hippie with a young woman on his shoulders, a floppy straw hat on her head. Another woman, who looks to be in her seventies, clutches her handbag, gaping in awe at the happy tower they form.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Music

- Janis Joplin

- Lewisville