This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

What set Clint Murchison, Jr., apart was that he enjoyed the hell out of his money. He was nearly broke by the time he died in late March, but he could still chuckle that when he sold his yacht to Frank Sinatra he pretended not to know who Sinatra was. Most of the other superrich I knew when I was a sportswriter in Dallas in the sixties—most notably Clint’s archrival, Lamar Hunt—seemed to begrudge their family fortunes. A dinner at Lamar’s house started with a game of one-on-one basketball in the back yard followed by tuna casserole. Lamar’s brother Bunker always seemed to have gravy stains on his necktie. My most cherished memory of Bunker is of him sitting on a bus parked outside the old Polo Grounds in New York. I was watching Bunker watch what he called “the great unwashed” burn trash to keep from freezing. It’s hard to imagine Clint Murchison shooting baskets or riding buses—the Polo Lounge, okay, but the Polo Grounds, never.

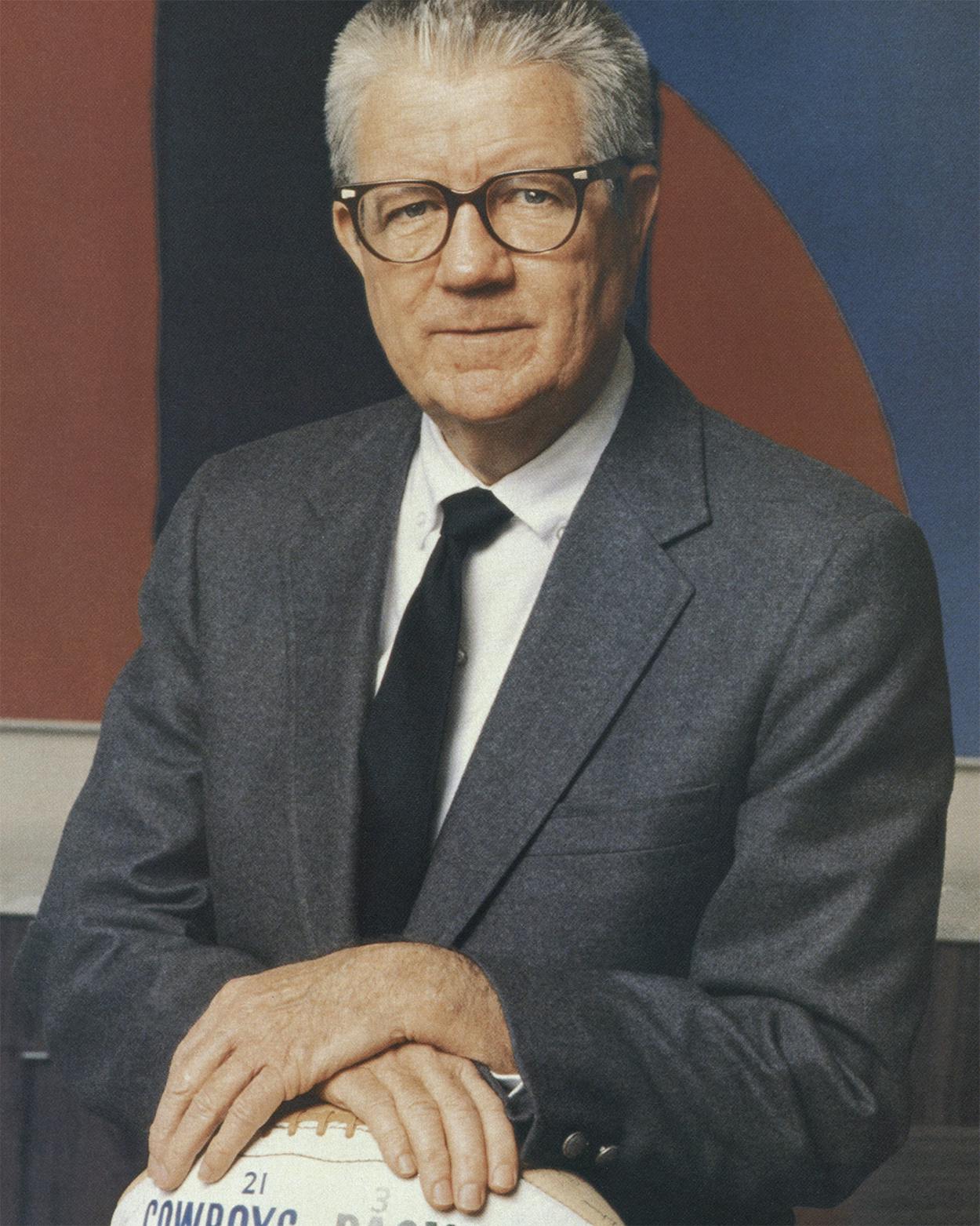

Clint was droll, reticent, and basically shy, preferring to remain above the fray. His crew cut, horn-rims, and impish smile belied power. He owned so many businesses that he sometimes forgot a few. When he asked his business associate Bill Dunagan to use some influence to find him a room in Palm Springs, California, Dunagan had to remind Murchison that he owned the Palm Springs Racquet Club. In the early sixties, when Murchison’s Cowboys and Lamar Hunt’s Texans were competing for our attention, Hunt invited writers assigned to cover his team to spend an evening with him in Las Vegas. Clint heard about this and quietly arranged for the Cowboys writers to spend five days on his private island in the Bahamas.

Whatever needed doing, Clint did with a word or gesture. When George Preston Marshall, the curmudgeon who used to own the Washington Redskins, tried to block Murchison’s effort to secure a National Football League franchise for Dallas, Clint bought the rights to the Redskins’ fight song from Marshall’s ex-wife and held it for ransom. Poor Marshall—he became a recurring target for the merry pranksters who orbited Murchison. Marshall loved elaborate halftime shows with lots of bands and live animal acts, and disaster was barely averted when a stadium guard caught Clint’s rowdies as they were trying to free several thousand live chickens while a dog team pulled Santa Claus down the field. The wicked genius behind the Chicken Club (as it was called thereafter) was Bob Thompson, Clint’s Marine Corps buddy who once got the two of them evicted from an exclusive hunting club by attacking a pheasant with a pool cue. But Clint didn’t mind. He loved it when Thompson’s pet turkey, Erik, relieved himself on the new carpet of Dallas tycoon Jim Ling. Clint’s style and humor reminded me of something Cole Porter might have written: too rich to worry, too bright to care.

Clint had a weakness for slumming and could show up anywhere at any hour. I once ran into him at a black bawdy house in Pittsburgh, and he occasionally dropped by the bachelor apartment that writer Bud Shrake and I shared. Newspaper types usually don’t feel comfortable around the superrich, but Clint had a way of making his own rules; the rest was easy. It bothered some that he was cozy with J. Edgar Hoover, a frequent houseguest. But as Dick Hitt noted in a recent Dallas Times Herald column, Clint redeemed himself on one of Hoover’s visits by hitching a live jackass to the staircase.

The Cowboys and general manager Tex Schramm learned to live with Murchison’s eccentricities. One year an aging barroom brawler showed up at camp, introduced himself as Rufus “Roughhouse” Page, and presented a contract signed by Clint Murchison. Tom Landry probably would have quit coaching years ago except that in 1964 Clint ordered an extraordinary ten-year extension to his contract. Texas Stadium was Clint’s idea too, as was the hole in the roof. I’d like to second Landry’s suggestion that it be renamed Murchison Stadium.

Clint was dying when I saw him last summer. Although his body was shriveled by Lou Gehrig’s disease, which eventually killed him, he insisted that Bill Dunagan and I load his wheelchair into a limo and take him to his favorite barbecue hangout. Clint could barely talk, but I caught a phrase: “Roughhouse Page. He’s saying Rufus ‘Roughhouse’ Page.” A look of triumph flashed across Clint’s face, backlighted by that old, familiar imp’s grin. I’ll remember him that way.

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Football

- Dallas