This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Norma Desmond, the fading movie star who is the central character in the Broadway hit Sunset Boulevard, probably would not have chosen Betty Buckley to portray her. The expansive, narcissistic, overly passionate, and consummately theatrical Norma—the protagonist in the classic Billy Wilder film on which the musical is based—might find Buckley a bit, well, small. Indeed, in her dressing room after a performance, the Fort Worth–born Buckley hardly seems up to the job. She makes her entrance in an artless terry cloth robe, her High Plains face sans even a trace of lipstick, and offers a simple, direct handshake. Only the photographs of spiritual guide Gurumayi Chidvilasananda and a congratulatory visit from celebrity psychoanalyst Mildred Newman (“I’ve known Betty a long, long time”) suggest the enormous vulnerability that’s required to take Norma on.

On stage, of course, no one could possibly doubt Buckley’s commitment. Night after night at the Minskoff Theatre, twice on Wednesdays and Sundays, she gives Norma all she’s got: She storms the massive staircase that is the centerpiece of the set, often wearing thirty-pound beaded gowns and two-and-a-half-inch heels, dramatizing the star’s collapse into madness as she comes to realize that the public that once breathlessly awaited her every move now has no use for her. The considerable acting skills of Buckley’s predecessor in the role, Glenn Close, made Norma live again, but it is Buckley’s singing voice—defiantly pure, packing a gale force yet simultaneously, impossibly fragile—that gives her a humanity and pathos she has never had before.

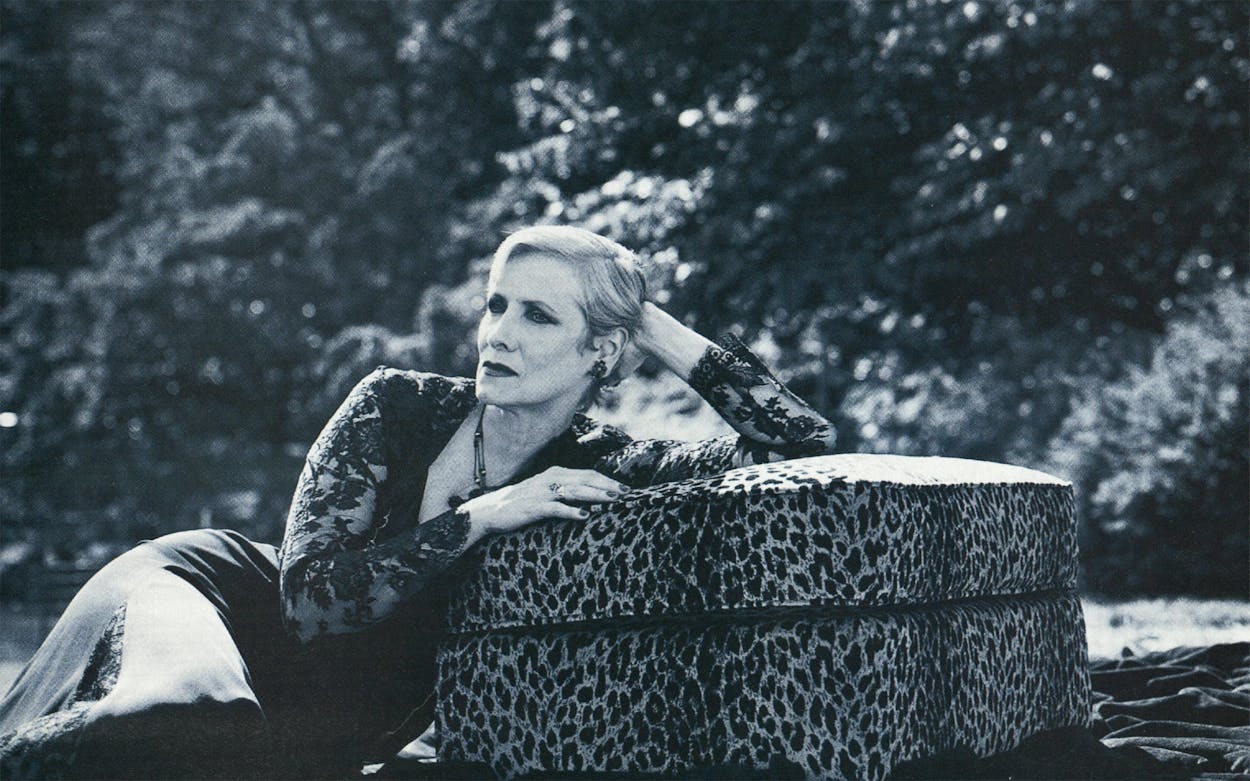

The 48-year-old Buckley is, in fact, the perfect actress for the role. “You must believe with your whole heart that you are the greatest, but be insecure enough to wonder if that could be true,” she wrote last year in a New York magazine essay advising other actresses how to play Norma. That description could also be applied to the whole of Buckley’s life. Her chronology may be different from Norma’s—the fictional character reached the pinnacle of her success as a very young woman, while Buckley has struggled well into middle age to achieve hers—but the combination of great determination and great delicacy is something both women share. Yes, Buckley pays lip service to getting her due at the proper time: “I’ve loved my career and I love the journey that I’ve had,” she says. “I’ve yet to meet a major superstar who has something better than I’ve got.” But the lines in her face and the solitary life that she has led hint at the price she has paid to realize her dream.

It is possible to wonder, too, whose dream it was in the beginning. “I knew when I was eleven,” Buckley says of her single lifetime ambition. “I had a very clear vision that I would go to Broadway and be a leading lady.” But her mother, Betty Bob, was a former tap dancer who had her own fantasies of stardom and sneaked young Betty Lynn out of the house for the dance lessons her husband so abhorred. “She stood me up in church and had me singing when I was five,” Buckley says. Even then, her voice had a power that belied her years. One teacher told her to walk to the back of the room and sing a line as loud as she could. “I finished singing, and there was this stunned silence,” she recalls.

Betty Lynn was a natural, but she was also a pro, even as a child. “She shouldn’t have been allowed to be in junior high talent shows,” jokes an Arlington Heights High School chum. “She was in another league.” In school contests, she performed with professional accompaniment and professional costumes; by the time she was 16, she was starring in revues at Six Flags and was Broadway bound at 21. It must have seemed preordained that she got her first part on her first day in New York, in the musical 1776.

Buckley did work steadily after that, appearing in Pippin, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, and other Broadway shows. She won a Tony award for her portrayal of Grizabella in Cats and kudos for her role opposite Robert Duvall in the film Tender Mercies, along with a lead on the hit TV show Eight Is Enough. But perhaps because of the dearth of roles for women, or perhaps because of certain Norma-like behavior that is tolerated only in stars of enormous magnitude—it would be easier to cut a deal with Oscar Wyatt than Betty Buckley—her magic moment has not come until now.

The timing seems eerily appropriate. The number of tear-stained tissues on view during Buckley’s curtain calls proves that she is an exceptionally successful vehicle for conveying the rage and fear everyone experiences when confronted with aging—and a culture that says you’re finished at forty. “All of Norma’s longings are universal,” Buckley says. “The need to be loved, to have a right to her sexuality. Norma, in her illusion, is basically fighting the good fight. She’s noble in her resistance.” Like Norma, Buckley has seen it all fade away: She had all but given up on Broadway when she got the call from producer Andrew Lloyd Webber to appear in Sunset.

Now, of course, she must live the life of a star playing a star, a feat that requires, at the same time, supreme indulgence and absolute discipline. “It takes a lot of work to serve Norma properly,” says Buckley, who then cites the chiropractor, physical therapist, psychoanalyst, manicurist, pedicurist, personal trainers, and masseurs she has enlisted in this struggle. “It takes a tremendous amount of support to create her on a nightly basis—spiritually, emotionally, physically.”

And the star has to know that stardom is as ephemeral as a Broadway run. At a trendy restaurant after one of her performances, Buckley, in leggings and a tired tunic, dines at a prominent table while her limo waits outside. Once the check is paid, once she has accepted congratulations from well-wishers, once she has exchanged we’re-both-on-Broadway glances with Ralph Fiennes of Hamlet, she gets up to leave, snatching the large unfinished bottle of water she had ordered with dinner. On the ride uptown she clutches it to her chest, something Norma would surely have understood.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Theater

- Celebrities

- Fort Worth