Judy, the airport barmaid, was off for the weekend but she showed no signs of leaving the lounge. She pressed against the wall-sized window and peered at the crowd in the lobby.

“Jeez,” she said, “there they are. Lookit. The Dallas Cowboys. Look how big some of those guys are.”

A man at the bar chided Judy for gawking. “I can’t help it,” she said. “It’s exciting. I never see anybody famous. Ooh, look, there’s Roger Staubach. He’s the only one I recognize.”

Behind the bar was Judy’s replacement for the evening shift. Several years older, Bonnie had nice legs and pleasant, skeptical eyes. Tilting a glass beneath the Coors tap, she asked Judy, “Who’s the big team where you come from—Green Bay?”

“Nah, nobody. Hey, look at Staubach. Now they got him signing autographs.”

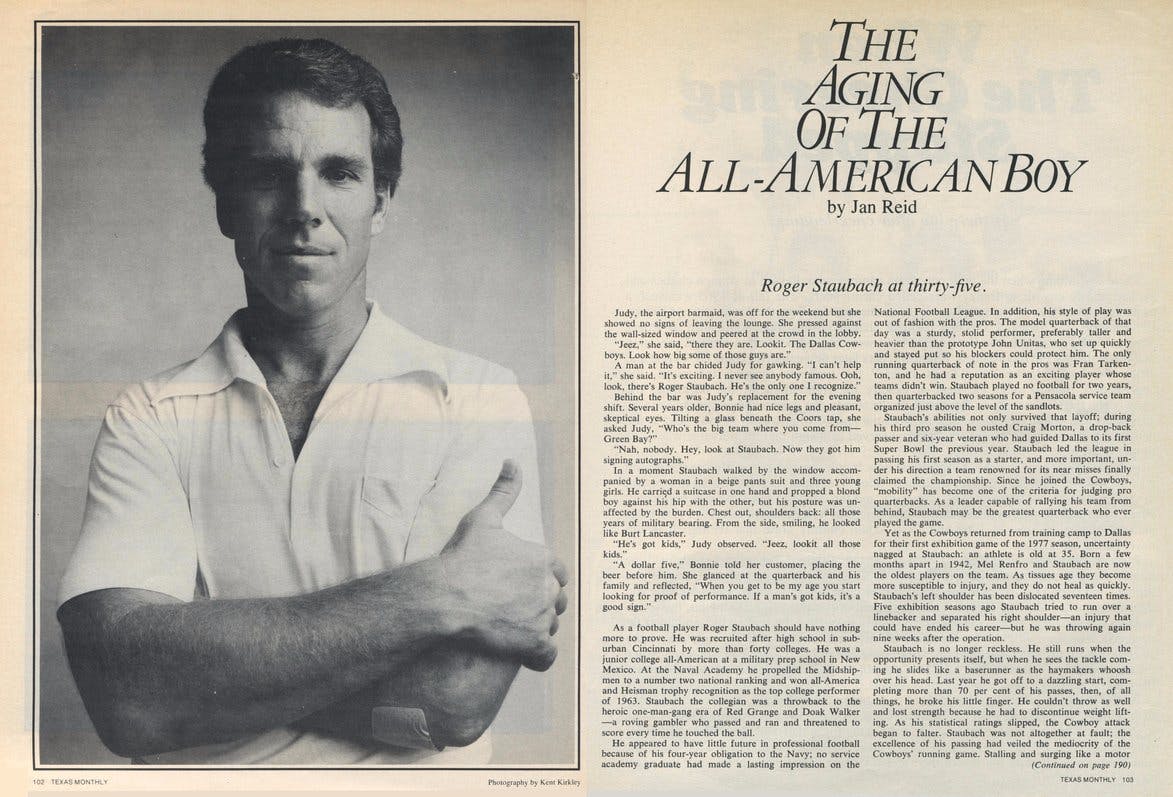

In a moment Staubach walked by the window accompanied by a woman in a beige pants suit and three young girls. He carried a suitcase in one hand and propped a blond boy against his hip with the other, but his posture was unaffected by the burden. Chest out, shoulders back: all those years of military bearing. From the side, smiling, he looked like Burt Lancaster.

“He’s got kids,” Judy observed. “Jeez, lookit all those kids.”

“A dollar five,” Bonnie told her customer, placing the beer before him. She glanced at the quarterback and his family and reflected, “When you get to be my age you start looking for proof of performance. If a man’s got kids, it’s a good sign.”

As a football player Roger Staubach should have nothing more to prove. He was recruited after high school in suburban Cincinnati by more than forty colleges. He was a junior college all-American at a military prep school in New Mexico. At the Naval Academy he propelled the Midshipmen to a number two national ranking and won all-America and Heisman trophy recognition as the top college performer of 1963. Staubach the collegian was a throwback to the heroic one-man-gang era of Red Grange and Doak Walker —a roving gambler who passed and ran and threatened to score every time he touched the ball.

He appeared to have little future in professional football because of his four-year obligation to the Navy; no service academy graduate had made a lasting impression on the National Football League. In addition, his style of play was out of fashion with the pros. The model quarterback of that day was a sturdy, stolid performer, preferably taller and heavier than the prototype John Unitas, who set up quickly and stayed put so his blockers could protect him. The only running quarterback of note in the pros was Fran Tarkenton, and he had a reputation as an exciting player whose teams didn’t win. Staubach played no football for two years, then quarterbacked two seasons for a Pensacola service team organized just above the level of the sandlots.

Staubach’s abilities not only survived that layoff; during his third pro season he ousted Craig Morton, a drop-back passer and six-year veteran who had guided Dallas to its first Super Bowl the previous year. Staubach led the league in passing his first season as a starter, and more important, under his direction a team renowned for its near misses finally claimed the championship. Since he joined the Cowboys, “mobility” has become one of the criteria for judging pro quarterbacks. As a leader capable of rallying his team from behind, Staubach may be the greatest quarterback who ever played the game.

Yet as the Cowboys returned from training camp to Dallas for their first exhibition game of the 1977 season, uncertainty nagged at Staubach: an athlete is old at 35. Born a few months apart in 1942, Mel Renfro and Staubach are now the oldest players on the team. As tissues age they become more susceptible to injury, and they do not heal as quickly. Staubach’s left shoulder has been dislocated seventeen times. Five exhibition seasons ago Staubach tried to run over a linebacker and separated his right shoulder—an injury that could have ended his career—but he was throwing again nine weeks after the operation.

Staubach is no longer reckless. He still runs when the opportunity presents itself, but when he sees the tackle coming he slides like a baserunner as the haymakers whoosh over his head. Last year he got off to a dazzling start, completing more than 70 per cent of his passes, then, of all things, he broke his little finger. He couldn’t throw as well and lost strength because he had to discontinue weight lifting. As his statistical ratings slipped, the Cowboy attack began to falter. Staubach was not altogether at fault; the excellence of his passing had veiled the mediocrity of the Cowboys’ running game. Stalling and surging like a motor running out of fuel, Dallas coasted into the play-offs. Against Los Angeles, Staubach’s passes nosed up and sailed incomplete. The Dallas defense provided ample scoring opportunities, but Staubach’s unit failed to do its part, and the Cowboys lost to a team with a rookie quarterback.

As a new season began, Staubach was under diminished pressure on the field. To the anguish of other championship contenders, the Cowboys drafted and signed Tony Dorsett by virtue of a complicated trade with Seattle. The moves of last year’s Heisman trophy winner are like the darts of a minnow; Cowboy scouts say the only running back prospect they ever rated higher was O. J. Simpson. With the Cowboys Staubach has never suffered from the quality of his surrounding personnel. Yet his zeal for football can never again be carefree. For an athlete with his self-discipline, staying in shape is not the problem. His fears at this point concern the tendonitis that might develop in his throwing arm, the blind-side tackle that could end it all. From now until he puts his shoulder pads away, Staubach will be trying to prove that he can still do the job.

At six or ten dollars a ticket, NFL exhibition games are difficult to sell. Dallas’ exhibition opener against San Diego offered a continuing shuffle of starters, reserves, and rookies, a dress rehearsal for the regular season. The temperature at game time promised to be in the midnineties, hardly an inducement for a large crowd. The angle hyped with greatest ardor in promoting the game was the “rematch” of Staubach and San Diego’s Clint Longley. Baby-faced and curly-haired, Longley was the unknown kid from Abilene Christian who rallied the Cowboys past the Washington Redskins on Thanksgiving Day, 1974, after Staubach was injured. Unfortunately, that was Longley’s only hour of Dallas glory. He rode the Cowboy bench, waiting for Staubach to yield again, until last year’s training camp, when tensions between them exploded twice in four days. Worthy of a grade school playground, the first fight ended with Staubach sitting on Longley’s chest. Longley then ambushed Staubach in the dressing room while he was removing his shoulder pads. Staubach spewed outrage and wore a Band-Aid over his eyebrow for a few days while the Cowboys traded Longley to San Diego, a frequent destination of Dallas castoffs. A year had passed since the fistfights, time enough for most hostilities to cool into indifference. Longley labored during the week behind a media screen erected by the Charger publicity director. “No comment,” Staubach rebuffed the Dallas Times Herald’s Frank Luksa. “I don’t care if he plays right tackle.” Still, the telecast of the game opened with a splitscreen juxtaposition of the two. “The Big One tonight in Texas Stadium,” intoned one Dallas radio voice. “The Cowboys and the Chargers. Staubach and Longley.”

The partial dome of Texas Stadium opens to the sky like the slot of a giant piggy bank. Viewed from the field, the lights in the spectator sections are blurred, indistinct, except for the scoreboard, a broad splash of yellow and black above the north goalpost. The playing field is a belly-shaped swell of artificial grass. The crowd murmurs, bellows, and sighs, but most of the discernible noise comes from the players.

Dodging a Charger lineman early in the second period, Staubach threw long with most of his weight on the wrong foot. Shouts of alarm and glee erupted as Cowboy flanker Butch Johnson ran under the ball 50 yards downfield for Dallas’ third touchdown. After the intermission Staubach put his helmet up. He sat on the bench some of the time, talking to Billy Joe Dupree, then knelt by himself and propped his chin in his hand. He stood up during the third quarter to watch the debut of Tony Dorset, who excited the crowd for a few plays then limped to the bench with a sore knee. Staubach hardly glanced at Longley.

The most impressive quarterback was Staubach’s current heir apparent, Danny White, who threw twice for scores to Drew Pearson. Longley played nearly three quarters and moved the Chargers no closer to a score than the Dallas 34. With no particular vengeance Cowboy defenders knocked him down and intercepted his intended bombs for Johnny Rodgers, the former Heisman trophy winner from Nebraska. A fourth-quarter pass by a rookie named Cliff Olander and a punt return by Rodgers spared San Diego the ignominy of a shutout, narrowing the score to 34-14.

As Longley entered the tunnel to the visitors’ dressing room his glance toward the crowd was quizzical, apprehensive. Soon he had shed his uniform and entered the shower, newsworthy in Dallas no more.

The spectacle of reporters begging profundities from men clad in athletic supporters places the term “jock” in sharper etymological focus. In the Dallas locker room the most frenzied crowd of newsmen surrounded a young black man who bears a marked facial resemblance to comedian Flip Wilson. The Cowboys have never had a rookie player who excited as much interest as Tony Dorsett. Perspiring, squinting at the television lights, explaining that he never promised he would gain 1500 yards his first pro season, Dorsett was backed against the wire equipment cage by more than a dozen shoving, shouting reporters. Blackie Sherrod, the legendary Dallas Times Herald sports columnist, watched that scene with an expression of fundamental weariness. Sherrod turned to Tex Schramm, the Cowboys’ general manager, and they exchanged the smiles of old comrades-in-arms. “What about you, Tex?” Sherrod said. “You got anything to say?”

Staubach walked by with a towel around his waist and grunted when Sherrod said, “Good game, Roger.” He nodded at ex-roommate Lee Roy Jordan, who was visiting in the locker room after watching his first game in the stands as a retired player, then claimed a lavatory and mirror. He shaved quickly, pinkie extended from his razor as if he were holding a wineglass. The notorious little finger of Staubach’s right hand looks like it has been pounded with a hammer; it juts outward at a 45-degree angle, and the second joint is the size of a small pecan. He combed his wet hair back and put on a gold shirt and Sansabelt trousers. Except for the gang around Dorsett, the crowd in the locker room had begun to thin out. Staubach told a radio interviewer, “I don’t think anybody resents all the attention Tony’s getting. He’s an exciting player. He’s exciting when he makes five yards.” But wasn’t Dorsett under a lot of pressure? Staubach nodded at the throng and said, “He’s under that kind of pressure, but he’s playing for a winning team. It’s not like he has to carry the franchise.”

As Staubach moved away from the radio interviewer a large man with a camera called his name. A second man with a parted Afro and a blue business suit thrust his chest forward when Staubach halted beside him. Staubach turned his torso toward the man in the suit and provided the static grin of an experienced photographic model. The strobe flashed. Staubach’s smile vanished and he left the men without another word.

Thousand Oaks, California, is the ultimate suburb. Forty miles up the Ventura Freeway from Los Angeles, its main street is a landscaped boulevard served by three shopping centers but no central business district. The roadsides are free of billboards and tall neon signs. The dry creekbed that winds through town has been paved. Avocado trees outnumber the oaks. Cool, soft air suggests the nearness of the ocean; hills with broken horizons fade into the haze. The sidewalks of Thousand Oaks are filled with ambling retirees and jogging children.

Beneath rock cliffs where a Jap sniper extinguished John Wayne during the filming of Iwo Jima is the modest, attractive campus of California Lutheran College, where the Cowboys have conducted training camp since 1963. After trying sites in Oregon, Minnesota, and Michigan, Tex Schramm talked about the team’s camp facilities with his friend Glenn Davis, the ex-Army halfback and special events director of the Los Angeles Times. Davis told Schramm that a new college was under construction at Thousand Oaks, and the Cowboys became the first occupants of the dormitories. Told more often is the apocryphal story, attributed to Don Meredith, in which Landry flew over the Conejo Valley, looked down, and said, “Let there be a college.”

California Lutheran has been an ideal location for the Dallas camp. The weather in August is always fair and mild, and there’s not much for the athletes to do in Thousand Oaks but play football. The week after the San Diego exhibition game they had little time for anything else. There was a team meeting every morning, and though the Cowboys were in their fifth week of camp and had played well against the Chargers, the two-a-day practice routine continued. The morning practice concluded at 11:30, specialty group meetings commenced at 1:30, and the Cowboys were back in pads from 3 till 5. After supper they attended more meetings and watched more films, with perhaps two or three hours of free time before curfew.

On Monday after the Cowboys returned to Thousand Oaks, Roger Staubach ate lunch, then sat on the hood of a car parked beside the coaches’ dorm. He wore a striped pullover, Bermuda shorts, and sneakers. I had not yet approached Staubach, and I was nervous when I introduced myself and shook his hand. His grip was powerful but his look was none too friendly. “Oh yeah, Texas Monthly. They gave me some kind of award last year. ‘Best Wimp.’ ”

Awkward mutterings: another reporter wrote that, and besides I’m just a freelancer and. . .

A Winnebago brimming with sun-shaded adults and preteen children pulled close to the curb and stopped. “I’ve got some friends to see,” Staubach said to me, moving toward the motor home. “The guys in the office told me you were going to be around here this week. I’ll talk to you later.”

I approached him again the next afternoon as he walked from the practice field toward the dressing room. “The wimp magazine,” he said when I fell in step beside him, but his tone was no longer hostile. “I just don’t understand where they got that word. To me a wimp is some skinny little guy that wears glasses, you know, an accountant. Somebody like Woody Allen.”

Staubach wiped his forehead with the sweatband on his wrist. “I’d like to talk to the guy who wrote that. And Clint Longley right after that.”

Staubach has a reputation for remembering every slight. He understands that he is in the entertainment business, but he is sensitive about his public image. Part of Staubach’s image problem derived from the act he had to follow. The Cowboys of the past were lovable losers of the Big Game; on and off the field they were flamboyant, colorful. When Cornell Green intercepted Don Meredith’s pass at practice one afternoon, Meredith chased him down the sidelines whooping and brandishing his helmet like a club. Walt Garrison was married to a Dallas heiress, but he really was a cowboy, a rodeo performer in the off-season. Garrison used to leap into rookies’ rooms at night and spit mouthfuls of lighter fluid through the flame of a butane lighter. Joey Heatherton hung around training camp waiting for Lance Rentzel, who violated so many curfews that one coach finally suggested Rentzel set a thousand-dollar tab aside to cover his fines. They were the Cowboys of the sixties, the models for Pete Gent’s novel North Dallas Forty.

It’s still a North Dallas franchise, but the Cowboys of the seventies have moved to the suburbs. Last year when Meredith was inducted into the Cowboy Ring of Honor, he gazed at the slotted dome and said, “I still say it’s a funnylooking stadium.” Surrounded by State Fair grounds and a black ghetto, Meredith’s Cowboys played on real grass beneath the yawning skies of the funky old Cotton Bowl. Upper-deck supports obstructed the view of many seats; blacks in the general admission section behind the end-zone screen chanted adulation for their heroes Bobby Hayes and Mel Renfro, who had to file suit in order to rent a duplex near the Cowboys’ North Dallas practice field. All seats are reserved in Irving’s functional, drab, and sterile Texas Stadium, the parking lot of which doubles as a drive-in theater. Discrimination against black players has diminished. Drew Pearson sells cars on TV. Harvey Martin has his own radio show.

Meredith announced his retirement on July 5, 1969, the day Staubach received his discharge from the Navy. Staubach’s behavior off the field was not totally at odds with his athletic daring. One day he showed up at the team’s executive offices on North Central Expressway in search of Tex Schramm. While Staubach fidgeted, Schramm rocked in his chair, staring out the window, making no effort to abbreviate his conference call. Staubach found a janitor who let him out on a narrow, unrailed ledge eleven stories above the parking lot, then made his point by leaping into the view of Schramm, who gasped, “Oh my god!” and almost overturned his chair.

But Staubach was no folksy Southern individualist like Meredith. He first saw Dallas at the age of eighteen, when he was on his way to New Mexico Military Institute, which he attended for a year at the behest of Navy football recruiters because he could not meet the English entrance requirements of the Academy. The military school in Roswell was not only a prep school for service academy aspirants; many cadets were the spoiled, unwanted, or problem sons of affluent Texans, and they demanded yes-sir treatment from jocks with Northern accents. From that day until he joined the Cowboys—as a cadet, plebe, midshipman, and supply officer—Staubach accommodated the restraints of military life for nine years. If Tom Landry wanted discipline on his team, Staubach knew all about that.

Football is not a verbal medium, and Staubach never talked about himself much until he quarterbacked the Cowboys to the league championship. After the Super Bowl win over Miami he received 200 requests a month for guest appearances. With all the product endorsements, banquet accolades, and plain old cash came speaker’s bureau hustlers, gawking crowds in restaurants, intense scrutiny of his every move.

He was dubbed a square. Voted Most Valuable Player of the game against the Dolphins, he told Sport magazine, which provides the MVP the keys of a new sports car, that his family needs were more along the lines of a station wagon. He informed a milk company that sponsors a most popular Cowboy contest that he didn’t have time for their free vacation—maybe they could give it to some “needy family.” Many players at that time were bitterly critical of pro football and society in general. Staubach said he chose that opportunity to stress the “positive” aspects of the sport and devote much of his time to “public service.” He kept his politics to himself but marched straight forward into the minefield of religion. “Each one of us has field position in life through the mind and free will given us by God,” Staubach told the Dallas youth council of the Salvation Army, “and we have someone to lead, guide, and direct us. God has given us a quarterback—Jesus Christ.”

Staubach became a champion of the middle class. Sports Father of the Year, Dallas chairman of the hemophilia March of Life Brigade, a member of the advisory board of the Salvation Army, here was a clean-cut, patriotic athlete, an all-American boy who had grown into an upstanding citizen. At the same time, groans arose from sophisticates who assumed he was yet another evangelist of simplistic, born-again, God-is-my-coach theology. On the other hand, if he admitted that he drank beer and enjoyed taking his wife to a nightclub, letters of abuse arrived from the fundamentalists. Still, Staubach is no religious fraud. A practicing Catholic, he graduated from a parochial high school, he was an altar boy at the Naval Academy, he attended mass the morning before Dallas won the Super Bowl. At a time when “out front” was a fashionable adjective, Staubach brooded that he was taking flak for simply being what he was. He lacked the flair of the Bobby Laynes, the Sonny Jurgensens, the Joe Namaths, the Don Merediths. Captain America wore Goody Two Shoes.

Staubach’s first pro start came during his rookie exhibition season against Baltimore. The Colts intercepted four of his passes and won handily, but Staubach rushed for more than a hundred yards, sweating off fifteen pounds in the August heat. “I hate him,” Colt lineman Bubba Smith said afterward. “I never ran so much in my life chasing anybody. I never want to play against that cat again.” As Staubach learned more he scrambled less out of desperation. He ran for first downs, not because he couldn’t see his open receivers. “One criticism of Roger’s passing was that he had a slow delivery,” said Ermal Allen, Tom Landry’s special assistant. “When he came to camp in 1971 he had one of the fastest deliveries in the game.” That year Staubach took over at quarterback and Dallas won the Super Bowl.

“Craig Morton never had a chance,” said Bob St. John, Cowboy reporter for the Dallas Morning News. “He was trying to lead a normal life. He’d finish the day tired and want a beer. Staubach would still be out there running laps and throwing passes. I used to watch Staubach and think, Jesus Christ, I’m glad he’s not after my job.”

Staubach the experienced quarterback rescued lost causes. In 1972, when Staubach tried to run over the linebacker and separated his shoulder, the Cowboys returned to the playoffs with Morton in the lineup, but San Francisco whipped them thoroughly and led by 15 points at the end of three quarters when Landry turned to Staubach. He was rusty, and with two minutes left in the game Dallas still trailed by 12. St. John and Cowboy publicity man Doug Todd gathered their papers and caught the Candlestick Park elevator toward the dressing room. The elevator door opened at a lower floor, and somebody informed them Staubach had just passed for a touchdown. When they got off the elevator a man with a transistor radio said Dallas had just recovered an onside kick. Before they could get back to the field Staubach struck again, and cold, unemotional Tom Landry ran up the tunnel toward them jabbering, waving the game ball, and leaping like Peter Pan. Staubach did the same thing in the 1975 playoffs when he threw the desperate pass that Drew Pearson somehow caught on his hip between two Minnesota Vikings. The Cowboys have lost their share of games with Staubach at quarterback, and they have not yet won another Super Bowl. But Staubach never chokes. As an old pro he has few weaknesses. Unlike Fran Tarkenton, he can still hit the sideline passes. The only quarterback who matches Staubach game after game is Oakland’s Kenny Stabler.

Some of the older men associated with the training camp have yearly liaisons with women in Thousand Oaks. Barmaids in town are hustled frenetically, but few women hang around the dormitory parking lot. Two who did were distraught the Tuesday after the Cowboys beat San Diego. “All of my friends have been cut,” one of the girls said. California Lutheran has a small summer enrollment. In the gymnasium and dormitories on the other end of the campus, junior-high-aged girls were attending a basketball camp sponsored by former UCLA coach John Wooden. The Cowboy players moved around campus in cutoff jeans and sandals, carrying their fine books and playbooks. The curfews, the fines, the scarcity of women gave the camp the feel of a military boarding school. Fines are administered like demerits. A player may be fined for missing curfew, putting his helmet on the ground, running a play without his chin strap snapped, getting a drink of water at practice without permission. The loss of one of Tom Landry’s playbooks seemed to be an unthinkable horror. The camp offered testimony to the principle that grown men can be treated like boys.

In the cafeteria at Thousand Oaks the Cowboy players tended to dine with their peers. One day at lunch Dorsett, who was nine years old when Staubach won his Heisman trophy, encountered the Cowboy commander at the water-glass rack. “Roger . . . dodger. . .” Dorsett began.

“. . . What?” Staubach replied. The two men moved away apologetic and embarrassed, no communication established at all.

“Hell, yes it’s complicated,” Dorsett later told me about the transition from college to the pros. “Every time they call a play it’s like a paragraph.” Concerning the Cowboy veterans, he reflected, “I look at some of these guys that have houses and families, and I think, man, to them I’m just a kid.”

Of 80 players on the Cowboy roster when they played San Diego, 58 were at least ten years younger than Staubach. Their respect for the older man was obvious. Even Danny White agreed that Roger was still number one. Staubach didn’t burden them with pep talks on the practice field. He stood with his helmet off, chatting when he was idle, and labored through the drills just like everybody else. To the younger players Staubach seemed mostly a reassuring presence. Their respect did not amount to veneration, but sometimes they were a little awed by his competitiveness. Staubach used to play pickup basketball at training camp with Cornell Green, who was an all-American forward in college. Now a Cowboy scout, Green grew reluctant to play with him, because when Staubach lost he insisted on playing another game. This year at Thousand Oaks Danny White beat Staubach in a game of ping-pong. Staubach threw his paddle through the wall.

To many veterans the younger players are a threat. The veterans understand that pro football teams can’t afford to featherbed positions for their old-timers, but Dallas management has a callous reputation because of its treatment of Meredith, Chuck Howley, Herb Adderley, and Dave Manders, among others. A notable absence at camp this year was guard Blaine Nye. An all-Pro, Nye was also popular among the players. He had talked about retiring for several years, but this summer he told the Cowboy front office he didn’t want to leave his home in northern California because of family considerations and asked them to work out a trade. Management informed Nye that neither Oakland nor the 49ers were sufficiently interested in an aging guard. Nye’s absence became a source of increased concern when another bulwark of the offensive line, tackle Rayfield Wright, injured his knee and underwent surgery. Some veterans felt the Cowboy executives might have cajoled Nye into reporting. Instead they shrugged his retirement off.

“No, I haven’t heard from Nye,” Landry said curtly in a press briefing at Thousand Oaks following the San Diego game.

“Have there been any more trade talks?” persisted the Morning News’ St. John.

“No.”

This kind of coldness often makes older players, like Staubach, think hard about their future.

Landry spends less time these days watching practices from a tower. He moves around the field calling occasionally for his bullhorn. He kids the players and his grin can be almost impish. His manner seems less impersonal than preoccupied, yet the forbidding distance of the man persists, reinforced by the nasal, atonal voice.

Asked once if he closed his eyes when Staubach ran with the ball, Landry replied, “No, I just sweat him out.” But Landry is an offensive innovator, and Staubach’s ability to run wisely adds another dimension to his play diagrams.

Staubach has complained that he is not a “complete” quarterback because Landry won’t let him call the plays. From Landry’s point of view, his insistence on calling the plays is no reflection on the abilities of Staubach. Landry says that he understands the offense best, and his assistants can read the situation better from the press box than Staubach can at ground level. Landry shows no signs of changing his mind, and it’s hard to argue with his system’s past success. Staubach doesn’t change many plays at the line of scrimmage because he doesn’t have to. Two-minute drills are worked out in advance of a game; most of Staubach’s miracle finishes have been recitations of a prepared script. He executes his technique, as Landry would say.

The Dallas Cowboys are a true corporate enterprise. George Allen has his thumbs on the whole operation of a Washington Redskins training camp. Landry at camp concerns himself only with football; other matters are handled by the general manager, the business manager, the publicity director. Even the players talk in terms of “the organization.” In that sense, Staubach is a quarterback created in Landry’s image and typifies the character and emotional bent of his team as much as Meredith typified his. Staubach sells real estate during the off-season. He lives in the same house he bought when he joined the Cowboys in 1969. The house faces a park in a Richardson neighborhood of weedless lawns, wooden shingles, sedans and station wagons parked side by side in the drive. The only thing that sets Staubach’s home apart from his neighbors’ is the Universal weight machine in the garage. The Cowboys of ’77 are the guys in the gray flannel sweats, and Staubach is the perfect organization man.

Staubach started jogging in preparation for the ’77 season the week after the Cowboys lost their ’76 play-off game to the Rams. He embarked on a new weight-lifting program before the Cowboys began their preseason training—a five-day weekly routine of strength work and running that started in late March. Staubach had been throwing to his receivers since April. Yet there was never a hint that he was bored by the monotony of the practices at Thousand Oaks. As the afternoon workout agonized toward the end, the players cleared the field for specialty team drills. “What the hell is Staubach doing covering kickoffs?” one of the tired veterans said.

While residents of Thousand Oaks pressed against the wire cage, the Cowboys strained against Nautilus weight machines under the supervision of training coach Bob Ward, a handsome, muscular 44-year-old man who looks ten years younger. Ward likes to talk about meditation, martial arts, and Russian physiologists. “For most people, from 35 on it’s a precipitous drop to oblivion,” he said. “But where most guys won’t do what we call extra-credit work, Staubach does it maybe to excess. He’s the one who’ll do more than he should do. You know that work, rest, and nutrition bit I was telling you about? Roger would be the guy who’d overdo it—more work is gonna make you better, which is not always true.

“Roger is very goal oriented, and he won’t ever let up. He establishes this image of himself and lives up to it. He couldn’t work any harder, and he could play as long as he wants. I mean look at the guy. He’s probably in better shape now than he’s ever been.”

The next day Staubach told me to join him for lunch. Between the Cowboy dressing room and the cafeteria he ran a gauntlet of teenaged girls who were attending Wooden’s basketball camp. One of them handed Staubach an autograph tablet. He scribbled on it and the girl turned the tablet sideways, frowning at the signature. “Who’s that?” she whispered.

Roger Staubach, I advised. She gasped, clasped her hand over her heart, and fell toward the flower bed.

Staubach shook his head, embarrassed, and murmured, “Girls that age. . .”

Staubach accepted a plate of roast beef and two half-pints of chocolate milk from the food line. He talked about his decision to “witness” his faith and reflected on his adopted hometown: “Dallas is a good place for kids to grow up in. I think it’s an interesting city. It’s got growing pains, racial problems, but every big city has those. Looking around the country—where I’d like to live—I can’t think of any place better than Dallas.” Recalling the frenzy that engulfed his life the winter and spring after Dallas won the Super Bowl, he thought for a moment and said, “That was . . . that was heck.”

Talking to Staubach, I thought he looked less like Burt Lancaster and more like Fred MacMurray.

“Maybe we can talk some more on the plane,” he said. “Oh, that’s right—you’re going back. . . I’m going up . . . Right. Seattle, Seattle.” Staubach sighed. “That was nice last week, going back for just a couple of days.”

He was eager to talk about North Dallas Forty the next afternoon, although he admitted he read only thirty pages of the book on a plane before he put it aside. “That’s a perfect example of the extreme in the sport. I’ve been with this team nine years and never experienced anything like that. I’m sure some of the guys smoke marijuana, but I’ve never been to a party where drugs were prevalent. It’s who you hang around with, apparently. I guess Gent hung around with those kind of people.

“A team has a lot of personalities. I suppose the older players help color the team personality. This isn’t a very old team. Back in those days the team was established. Don Meredith was a very colorful guy, a great personality, and I thought he was a fine quarterback. He went through some tough years with the team, and he played with injuries. I think he got tired of people not appreciating him. He probably had other reasons for retiring early—I don’t know him all that well—but he was kind of the personality of that team, where now to some degree I might be. I’m not all that colorful, I’ve got a family, but I’m not any dud either. I’m not out carousing, but I don’t say that’s particularly wrong.

“A lot of people assume Landry and I are close because of our philosophies off the field. But our athletic philosophies are very different. I was a running quarterback. Craig was a drop-back passer, he’d been programmed to take over, and he would have, but he got hurt. I like to think I’ve earned everything I’ve had athletically. I have my own social life. I don’t have much chance to see Landry, other than as a quarterback. I think he’s a fine example as a Christian. But my beliefs are my beliefs. I’d hate to have people say Staubach and Landry got together because of their religion.

“It’s really Landry who sets the tone for this team. He’s an administrator, and he’s very disciplined. I know players who’ve gone on to other teams and they say, ‘Wow, the coach asked me into his office and we sat down over some beers,’ but about a year later they’re saying, ‘Hey, this isn’t as good as I thought it was going to be.’ You’ve got to have discipline. Landry is a difficult man to understand. He’s aloof but in a commanding sort of way. Landry’s the one . . .

“I don’t take anybody to task if his lifestyle differs from mine. Lifestyle really doesn’t have much to do with it—what the guys have in common is mutual respect for their athletic abilities. My closest friends right now are guys I played with in college. We were together all the time. Here the players are married and have families and are spread out. Training camp is about the only time we’re together a great deal outside the athletic environment.

“As for the younger players, there’s a generation gap. I used to room with Lee Roy Jordan but now it’s Bob Breunig. He was saying the other night, ‘Rooming with Roger is like rooming with my father.’ ” Staubach chuckled. “You don’t share the same things in life with the younger players because it’s been a different experience. Really you just relate to them on the field.”

Practice that afternoon attracted a larger crowd than normal. One visitor was Walt Garrison, sent to California by his snuff company to publicize a horse race. Garrison wears a larger size of jeans now but he is still broad-shouldered and jut-jawed. Reporters flew toward him like bees to a hive.

“Slow as death,” Garrison replied when asked about his speed. “I think the last time they clocked me in the forty I ran about a five-one. Blistered their ass.”

Somebody asked him if he missed football.

“Would you miss gettin’ the shit beat out of you once a week? I like not having to listen to Tom Landry and Tex Schramm. I’m not saying I wouldn’t listen to ’em, but it’s a nice feeling not to have to.

“The first and probably the last,” he said of his return to Thousand Oaks. “Kinda like screwin’ a skunk, I’ve enjoyed about all of this I can stand. Excuse me, I have to go say hello to Roger.”

It was official autograph day for the kids in the bleachers. After practice ended they ran on the field and sought out their favorite players. They milled around Staubach while Landry cautioned, “Now don’t shove, don’t crowd up too close around him.” A woman brought a trembling old man in a wheel chair up to Staubach. He smiled and reached over the kids to shake the old man’s hand, and recalled sitting beside him at some dinner. As Staubach signed autographs other adults focused their cameras. “Roger . . . Roger,” they said, the way you’d try to make a horse or a dog prick up its ears.

The jet’s wing lowered over the inky Pacific, the cluttered blocks and ordered groves of the San Fernando Valley, the parched terrain beyond. In a few hours the Cowboys would take the field in Seattle. I thought again of Staubach. One of those afternoon practices—the sameness melds them all together—Staubach was throwing sideline passes to his receivers. Those were the only drills I liked to watch: the long stride of Staubach’s delivery, the taut spiral of the ball, the ballet grace of the receivers getting both feet down in bounds. Upheld a whistle blew. Arms crossed over his chest, Landry offered some suggestion as the quarterbacks and receivers took off trotting. “Holy cow,” Roger enthused, “I’ll have to work on that!”