Jake Silverstein: Your new book, Custer, is about the Battle of the Little Bighorn. This is, of course, a well-covered subject, the subject of thousands of books and paintings. Why have we, as a nation, continued to return to this story?

Larry McMurtry: It’s kind of the end of the American settlement narrative. That’s where it stops. It’s almost paradoxical. The Indians—it might have looked like they won, but in fact they lost. Because after that, there was relentless pursuit, and it was all over. I think that’s mainly it. Custer really was a dashing young general, though most Americans didn’t know what an awful man he was. They only knew that he represented them in some specious way. So defeat in a major battle seems to resonate even more than victory. If he’d won the same battle, it probably wouldn’t have had the dramatic force that it has.

JS: We think of the Alamo in a similar way.

LM: Exactly. If [the Texians] had won, the Alamo wouldn’t be a big deal.

JS: Little Bighorn was a terrible miscalculation on Custer’s part. You have said elsewhere that a great theme of your work has been human folly. Does Custer fit into that?

LM: He certainly was foolish. The intriguing thing to me is that all the scouts told him not to go down into the valley of the Little Bighorn. All of them said, “If you do, you’ll be dead.” And not only did he ignore them, they followed him, and they knew they were going to be killed. Why they followed him I’ve never been able to fathom.

JS: Do you see that theme of human folly running through the history of the West at large?

LM: Oh, I haven’t really sat down to think about it in those terms. There was an abundance of folly in the Old West, that’s for sure.

JS: You’ve written in the past about how the cattle kingdom was very short-lived, in part because the cattlemen on the central plains were simply using the wrong animal.

LM: The wrong animal. And eliminated the right animal.

JS: These were, of course, the English breeds that were brought in to replace not just the Mexican Longhorns but the native buffalo as well, both of which were adapted to the land and climate.

LM: Right, right. They were English cattle. Shorthorns.

JS: That seems like the quintessential example of human folly.

LM: They couldn’t believe that their cattle couldn’t flourish with such an abundance of grass. But in fact the cattle couldn’t stand the winters. Eighteen eighty-five to 1886 was particularly bad, and it cost some of those cattlemen. One cattleman, a man named Granville Stuart, a Montana rancher, lost $20 million. That’s a huge financial loss for that time.

JS: At the beginning of your writing career, you sort of avoided the subject of the Old West as a setting. But eventually you came around to it.

LM: Eventually I ran out of modern-era things to write about. I’d written several domestic novels, like Terms of Endearment, and I was looking around for something I could write. The Old West began to appeal. I set out to demythologize it, but you can’t. The readers want the myth. They’ll turn it into the myth no matter what I do. Look at Lonesome Dove. I thought of Lonesome Dove as a book that would demolish the myths. But instead it just enhanced them.

JS: Your personal history is rooted in that time and place. Your father was a rancher, and you’ve written very movingly about his devotion to that life.

LM: He loved the ranching life.

JS: But he knew it was not going to last beyond his time.

LM: It just barely did. He was in debt 55 years, he told me not long before he died. He got to do what he wanted to do, but he essentially worked for the bank. He would not have survived if he didn’t live in a time of cheap credit; my father was paying 2 or 3 percent on the loans that kept him going. If he’d had to pay the kinds of rates that we pay nowadays, it wouldn’t have worked.

JS: But there are obviously still ranches all around Texas on which cows are raised.

LM: They’re funded by oil in most cases. Oil and gas. They aren’t dependent strictly on cattle. They just wouldn’t survive if they were. The King Ranch is a major ranch, but it’s not funded by cattle. It has immense oil and gas holdings. And that is very much [the case with] all the ranches.

JS: You didn’t follow in your dad’s footsteps. I think you said once that you were a book rancher instead. In August you sold a lot of the books at your stores in Archer City. And a few years ago, at Rice, you gave a talk in which you said that the culture of the book was going away. What made you say that?

LM: Well, I just think it’s fading. I was happy with the book sale because a lot of the young dealers showed up. And yet there were only a handful of them, really.

JS: In your book Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen, you make a series of observations about how an increase in media consumption has corresponded with a decrease in time spent swapping tales. You say that when you were younger there was no media and now, it seems, there is no life. That book was published thirteen years ago, before the Internet had really begun to transform society. I wonder if you feel that we’re now much further along in that process.

LM: We’re pretty far along. The hardest decision I had to make with the books I sold in Archer City was [whether to sell] my reference books. They’ve been accumulated over forty years. They’re a very good physical reference library. And it occurred to me that they represent a kind of ideal of bookselling, when any normal dealer would have had the British Museum catalog and the auction records and stuff like that. The Internet has made those books obsolete. You don’t need them. You can get all of that off the Internet.

JS: And is that a step forward?

LM: A step backward.

JS: Why?

LM: I think that’s a loss of hands-on, self-generated bookselling. It seems to be slipping away.

JS: I wonder if we might turn briefly to politics. About a year ago, you wrote a piece for the New York Review of Books website about Governor Perry, who had recently entered the presidential campaign. You called him a “slicked-up trash mouth . . . whose only salient principle seems to be that all attention is good.”

LM: That’s right. I think he’s a disastrous governor. He’s all about getting attention for himself, and that’s what he’s mainly doing as far as I can tell.

JS: Unlike his predecessor, George W. Bush, he’s a true product of the frontier—he traces his roots back many generations in Haskell County. Do you think his policies or politics in any way represent a frontier mentality?

LM: Oh, sort of, in a crude fashion. He represents a kind of frontier conservatism that doesn’t take you very far.

JS: Where would Rick Perry fit in Custer’s world?

LM: He would be an ultraconservative general. Like [Custer’s commanding officer, Philip] Sheridan, maybe, who had an absolute belief in his own righteousness. That’s where he’d be. He would be all for Custer.

- More About:

- Books

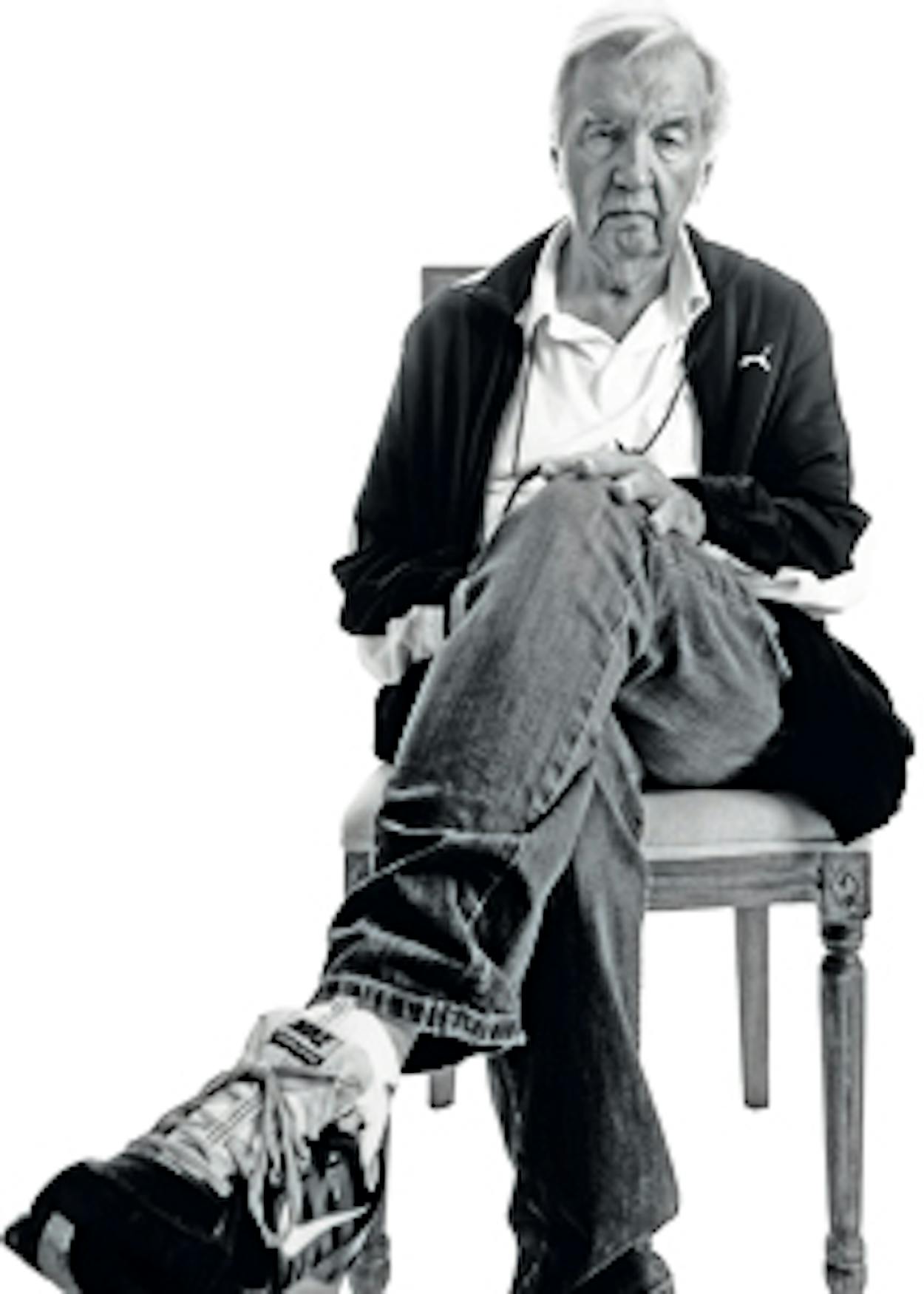

- Larry McMurtry