This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Austin’s number one, long-hair, honky-tonk, Armadillo World Headquarters, always draws a crowd Saturday night. The Armadillo, an abandoned armory adjacent to a skating rink, has already attracted its share of myth, mystique, and tall tales. Its concrete floors temper the urge to dance with the fear of shin splints, its walls bear some artwork of modest inspiration, and there is apparently no way to air-condition the damn thing. However, the Armadillo has a license to sell beer, some pretty fair food for sale, surprisingly good acoustics, and for the heat-exhausted, an outdoor beer garden. And most important to the faithful who part with their money one Saturday night after another, Armadillo offers some of the best live music in the country.

Getting things started the night of April 7 was Whistler, Austin’s first country-rock band, together again for the first time in nearly two years. They got a nostalgic reception. Then came Man Mountain and the Green Slime Boys, four converted San Antonio rock & rollers who offer original lyrics in the Nashville mode but can still bring the house down with a revival of the 1957 Cadillacs hit, “Speedo.” The crowd got off to Man Mountain, bringing them back for an encore, a tribute which left the boys a little abashed, considering who was waiting in the wings.

Even before country music became fashionable, it was possible to appreciate the music of Willie Nelson: His lyrics seemed to grasp the problems associated with coming of age in Texas, even as his voice rubbed them in.

Ten years ago Willie Nelson wore business suits for his national television appearances; for the Armadillo audience he was a little looser: boots, beard, cowboy hat, and gold earring. Nelson may look different, but except for the addition of some rock licks and lyrical references to Rita Coolidge’s cleavage, his music hasn’t changed all that much. His old songs—“Hello, Walls,” “The Party’s Over,” “Yesterday’s Wine”—still evoke memories of beery nights and jukeboxes, but they blend nicely with the newer, more upbeat numbers. Onstage, Nelson accepts praise with an irresistible smile, yet never lets audience enthusiasm interfere with his standard act, a non-stop, carefully-rehearsed medley of his own tunes.

As remarkable as Nelson’s act that night was his audience. While freaks in gingham gowns and cowboy boots sashayed like they invented country music, remnants of Willie’s old audiences had themselves a time too. A prim little grandmother from Taylor sat at a table beaming with excitement. “Oh lord, hon,” she said, “I got ever’ one of Willie’s records, but I never got to see him before.” A booted, western-dress beauty drove down from Waxahachie for the show, and she said, “I just love Willie Nelson and I’d drive anywhere to see him . . . but you know, he’s sure been doin’ some changin’ lately.” She looked around. “I have never seen so many hippies in all my life.”

The crowd kept pressing toward the stage, resulting in a bobbing, visually bizarre mix of beehive hairdos, naked midriffs, and bare hippie feet. An aging man in a sportcoat and turtleneck stubbed out his cigar and dragged his wife into the madness, where she received a jolt she probably did not deserve: a marijuana cigarette passed in front of her face. A young girl, noticing the woman’s discomfort, looked the woman in the eye, and took another hit.

But Nelson’s music relieved any cultural strain that developed beneath him. He played straight through for nearly two hours, singing all his recorded songs then starting over. They handed him beer, threw bluebonnets onstage, yelled, “We love you, Willie”—a sentiment he returned when he finally called it quits: “I love you all. Good night.” A night that for many had been a sort of hillbilly heaven, though Tex Ritter would have undoubtedly taken issue with the form.

The April 7 Willie Nelson concert was not all that unusual. Nelson is merely the most established of a gang of performers who have distilled a blend of music that reflects the background, outlook and needs of a unique Austin audience. The audience is largely comprised of middle class youths who hail from Texas’ cities yet are rarely more than two or three generations removed from more rural times; they came to Austin because the feel of those rural times still lingers there. In a way, they are a new breed of conservative who despair over big-city hype and 20th-century progress and romanticizes “getting back to the land.”

However, they are inescapably children of the mid-20th century: They grew up with their fingers on radio dials and stereo headsets clamped over their ears. Their need for music is insatiable. Living in Texas, they grew up with country & western, which in its whining way has stressed themes of bewildered displacement for years. The performers popular in Austin today also grew up with country music, and by sophisticating the lyrics and upbeating the tempo they have transformed country from a music of middle-class misery to one of down-home delight.

Austin musicians were not the first to borrow from country music; indeed, one of the Austin lyricists writes. “Them city-slicker pickers got a lot of slicker licks than you and me.” But Los Angeles country rock is slick rather than soulful: West Coast musicians are generally too citified to play country without a trace of put-down. In Austin the roots are real. The music rings true and that ring could establish Austin as America’s next cultural sub-capital.

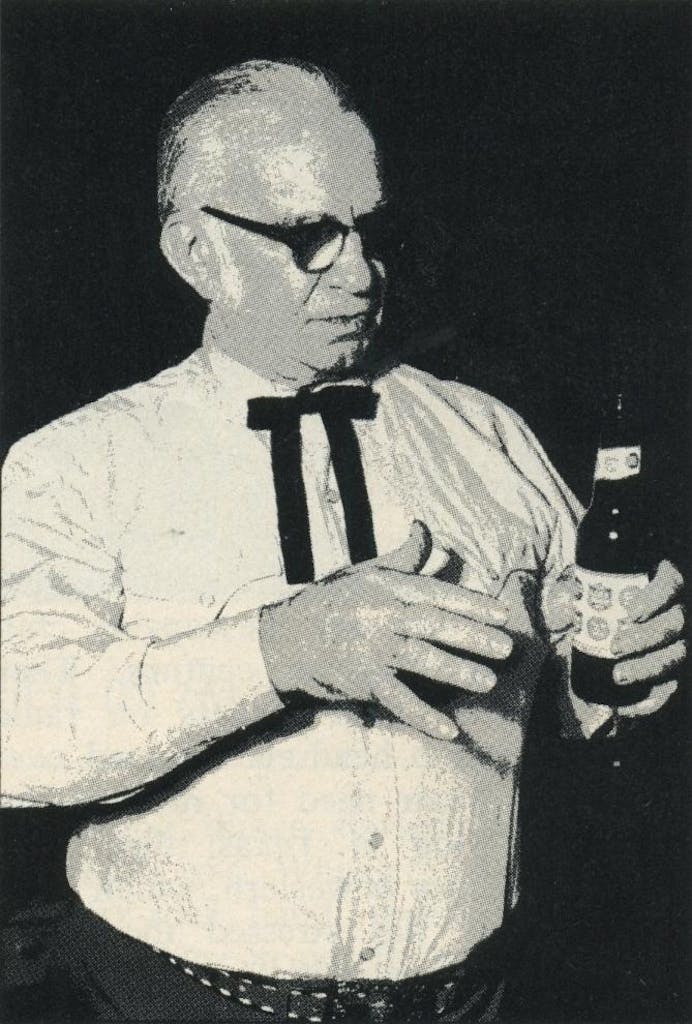

Austin’s easy-going mix of musical styles did not originate with Armadillo World Headquarters it dates back to 1933, when Kenneth Threadgill purchased Travis County’s first beer license and turned a little filling station on North Lamar into a bar that reverberated one night a week with the liveliest music in Austin. The houseband was straight hillbilly. Threadgill himself highlighted the jam sessions with his Jimmie Rodgers yodeling, but he had an ear for almost any kind of music. The mike was open to anybody with the nerve to stand up and sing. Threadgill was also the first of Austin’s clubowners to realize there was gold in those university hills. Anybody interested in a good time was welcome in his place.

Musically, the most exciting days at Threadgill’s were the early sixties, when the little bar became a haven for folk purists who were reaching deep into America’s musical heritage of white country, black blues, and backwoods ballads. The most memorable of those performers was a young woman named Janis Joplin who wandered in one day carrying an autoharp. Janis of course went on to a meteoric career, but she never forgot the cherubic old man in the gas station music hall. Before she died she told a surfacing songwriter named Kris Kristofferson about her old patron. In 1972 zealous fire marshals forced Threadgill to close his bar, but the same year Kristofferson looked him up at a party in Austin, listened to his music, and in three weeks had Threadgill in Nashville recording his first album. Thus things have come full circle for Austin’s kindly 63-year-old patriarch.

At Threadgill’s one heard just about any kind of music that fingers could make, but the little bar couldn’t contain aIl the musical excitement that seized the country during the sixties: Rock ’n Roll. The bands that sprang up in Austin were hard up for somewhere to play until 1967 when a group of friends secured a location on south Congress and built themselves a rock & roll joint, incurring the universal wrath of the Austin establishment. The Vulcan Gas Company never had a beer license, which meant the only revenue came from the gate, but Lockett booked the best of Texas’ black blues singers, carefully spaced between Austin rock bands that kept the place jumping. Two of those house bands, Conqueroo and the Thirteenth Floor Elevator, attracted fanatical followings who came out with ritualized regularity to watch their electric leaders perform. The stoned crowds of teeny boppers, proto-hippies, and servicemen bore little resemblance to the beer-drinkers at Threadgill’s, but rock & roll had come to Austin.

Unfortunately, the Vulcan scene soured. The club’s cult rockers quickly found the music business wasn’t all incense and acid: The Elevator was the victim of an unfortunate recording contract, and the Conqueroo found that San Francisco’s rock gurus had no use for bands from Texas. And at home, psychedelics had turned into speed and Vietnam violence had spilled over into the Vulcan. Tired of the hassle, Lockett looked for someone to take over the Vulcan, but none of the new managers worked out, and the club died in 1970.

Eddie Wilson, whose Armadillo World Headquarters rose from the ashes of the extinct Vulcan, got into the music business in a roundabout manner. “A mediocre jock, hot-rodder, and general slob” at Austin’s McCallum High, Wilson wound up at North Texas State in 1963, where he joined the campus folk music club. Another member of that club, Spencer Perskin, went on the provide vocals, lead guitar, and electric fiddle for Shiva’s Headband, an Austin group that became the Vulcan’s last cult band after the dissolution of Conqueroo and the Elevator. Perskin looked up Wilson in 1969 and asked his old friend to manage the band, precisely because Wilson didn’t know anything about the music business. “The people on the street needed to feel that their fellow street hippies who were making music were into it in a pure sort of way,” Wilson explains.

Shiva’s eventually died the commercial death it apparently wanted, but the man who became the prime commercial mover of Austin music had entered the business. After the Vulcan closed Wilson started looking for a suitable site for a new club, found the abandoned armory in south Austin, and with his friends (particularly Jim Franklin, a graphic artist and veteran of the Vulcan scene who was fast creating a visual cult of the nine-banded armadillo) he turned the building into “the archetype of the ugly, cold, uncomfortable rock and roll emporium.”

Armadillo opened in August 1970 to the anguish of establishment spokesmen who thought the flea-bitten menace had died with the Vulcan. Since then the Armadillo has grown, like its namesake, by rooting and foraging. First came the beer license, then a new stage, tables and chairs, heating, an improved sound system, and most recently, the beer garden that offers a measure of economic security. But most important, word has spread among performers that Armadillo’s audiences are perhaps the most spontaneous and appreciative in the country. The bellowing, stomping, cowboy-hatted mobs can scare a tough-assed lady like Bette Midler, but more often they win the affection of a John Prine, a Waylon Jennings, a Gram Parsons. As a result the national reputation-makers have been very kind to Eddie Wilson and his Armadillo, and he is now booking acts that he once could barely afford to phone.

The Armadillo has undoubtedly been the catalyst of Austin’s musical development, but other young music extrepreneurs have followed Eddie Wilson’s lead. Doug Moyes and Ric Schwartz offer smaller, quieter settings in their clubs—Castle Creek and the Saxon Pub respectively—to many of the same artists who play Armadillo. At 23, Larry Watkins has seven years of managerial experience behind him and has landed recording contracts and major concert dates for a number of local musicians. A heavy-set disc jockey for KOKE-FM named Rusty Bell pioneered a “progressive country” format that mirrors the sound of Austin’s country-rock blend. A former rock musician, Jay Podolnick, is converting an old cleaning factory into one of the few 24-track recording studios in the country. Austin thus has all the accoutrements of a full-fledged music center, and it is by far the most music-oriented Texas city. Aspiring musicians have countless live music bars to perform in, and though the pay for gigs varies, they need never worry about playing to an empty house. Musically at least, all roads in Texas lead to Austin.

A widening circle of poet/songwriters have in the last two years followed those roads to Austin. Steve Frumholz, Jerry Jeff Walker, B.W. Stevenson and Michael Murphey have led the flight from corporate songwriting factories, uptight New York streets, and cutthroat California clubs. These leaders of Austin’s musical renaissance deserted the big-time’s career opportunities for a community of reasons. Murphey sought musical electicism, Stevenson sought a cross-sectional audience, Walker sought peace and quiet, Frumholtz sought country people for neighbors. In Austin they joined up with an “Interchangeable Band” of sidemen who work smoothly behind any of the major performers. The backup men come mainly from the rock copy bands of the sixties, and as folk-oriented Steve Frumholz observes, “Our sidemen have made us boogie a little bit more, but at the same time, they’re willing to play softer music, although they can still kick ass when it’s time to.” But more than music unites the four writers and their sidemen. Frumholz puts it this way: “Everybody loves it down here—they can sit and drink Lone Star and fall out if they want to. Nobody’s laying any trips on anybody else. There’s no ego hassle.”

Frumholz spent much of his boyhood in a bypassed little Brazos town called Kopperl, and as a result is the Larry McMurtry of the Austin songwriters: His lyrics can be a little tedious, but he has a great eye and ear for detail, and many of his songs tell vivid stories about a Texas slowly dying out. When a crowd is rude Frumholz is capable of resorting to non-stop rum and sodas, turning his back, and plugging into a rock & roll just as raucous and rude. But when they’re attentive, he reaches back for a lot in his music, and he is the most entertaining of the Austin country rockers, for he has the best sense of humor.

Frumholz is quoted on the liner notes of a friend’s album: “Jerry Jeff: Indeci‘ion may or may not be your problem.” Jerry Jeff Walker grew up on the fringes of a little town in upstate New York listening to Buddy Holly and Everly Brothers rockabilly, and the more he listened to pop music, the more he thought: “I met a girl at the hop/she left me at the soda shop—hell, 35-year-old men are retiring writing that.”

Jerry Jeff wrote songs and coped with New York for a few years, but after his marriage broke up he started practicing what he sings about: a drifting way of life. He hitched through Austin the first time in 1964, but his most fortunate overnight stay was in New Orleans, when he met an alcoholic minstrel dancer in a drunk tank who inspired the song “Mr. Bojangles.”

Walker could probably live off the royalties of that classic song, but he kept on writing and moving, looking for “a place to camp the wagons.” Walker remembered the clubs and musicians in Austin, and the charms of the bordering Hill Country—not just its green distances and soft summer rains, but its people, who in Walker’s thinking have realized their good fortune and turned their backs to the maddening tangle urban America is becoming. In 1972 he unhitched his team in front of a $50,000 home west of town.

Also in demand for club dates is B. W. “Buckwheat” Stevenson, though that wasn’t always the case. Stevenson remembers lean days on the West Coast: “It’s real hard to do anything in California unless you have somebody with a cigar in his mouth and a recording contract. You bring your tape to a clubowner, who says, ‘Yeah kid, that’s real nice, we’ll ta1k to you later.’ And you know he hasn’t even listened to the sonofabitch.” Ironically, however, Stevenson had to record an album in California before he could land a gig in Austin.

Short, rotund, with a Dan Blocker hat, holy moses beard, and elfin smile. Buckwheat is the “kid” of the Austin movers. He grew up in Dallas, and landed a scholarship to North Texas by virtue of a wide-ranging, almost perfectly textured voice. Booted out a year later, Stevenson joined the Air Force, and started writing songs only after a bitter love affair. At 25 B.W. now has three albums to his credit, but has learned that a recording contract can create as many problems as it solves.

“Everybody in the company thinks I need a hit record. But that’s not going to make me anything more than I am. What I really want is to grow in my songwriting ability and stability of person.” So far, Buckwheat has yet to release an album totally in his own concept. His most effective material is understated, but Hollywood producers insist on surrounding his great voice with horns and strings, sending it over hill and dale in search of a hit.

Michael Murphey delights in Buckwheat’s interpretations of his material, goes fishing with Jerry Jeff, and once formed a folk trio with Frumholtz, which broke up because “We both liked Patty, and she only liked one of us, and the one she liked wasn’t me—she married a football player, probably the smartest one of all.”

However, Murphey stands a little apart from his colleagues, perhaps because intellectuals are always somewhat aloof. He went to North Texas because he wanted to be a Baptist preacher and needed to learn classical Greek in order to study the original texts; the lyrics for his most ambitious song—“South Canadian River”—derive from, of all things, the philosophy of Albert Schweitzer; in order to be sure he does not sit down to write a song one morning and have nothing to write about, Murphey files all turns of phrase which catch his ear and tabulates them to the very syllable, which means that an intelligent person can construct from his files a poetic, syntactically perfect sentence that makes no sense at all.

The classical poets in North Texas’ library diverted Murphey from his conservative Dallas direction, and after graduation he spent a half-dozen formative years in Los Angeles, turning out over 400 songs for Screen Gems from nine-to-five then hurrying across town in the evenings to play backup bass in obscure country bars. Screen Gems treated him fairly, but he got ripped off by several publishers along the way. By 1970 he had developed a tough business sense and word was spreading that he was perhaps the most gifted young lyricist in the country, but he got homesick for Texas, and home he and his family went.

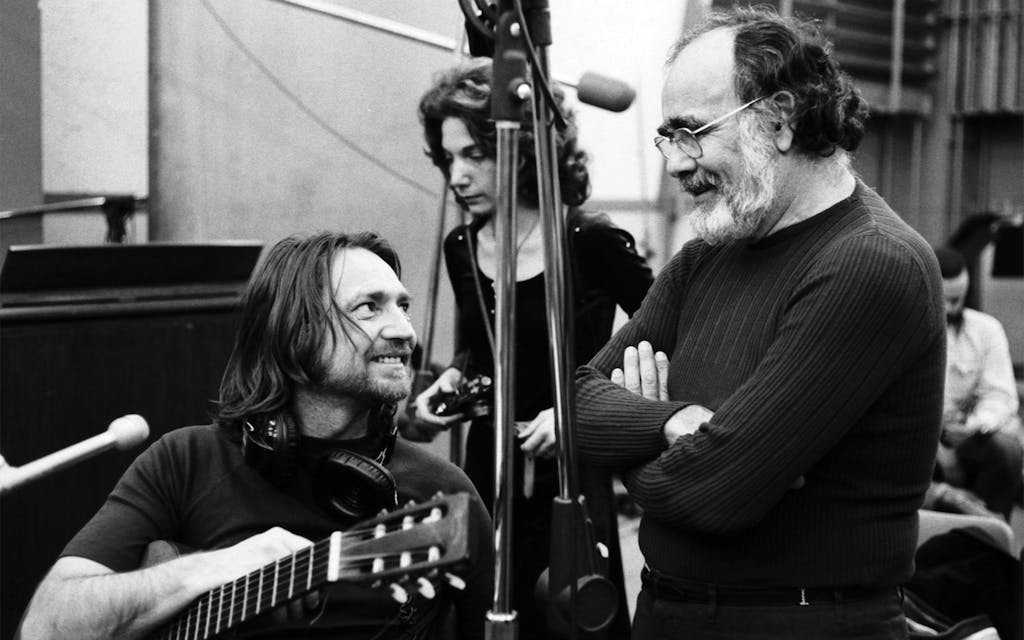

Murphey’s producer, Bob Johnston, in the past produced Bob Dylan, the Band, and Leonard Cohen; with that credential Murphey can record anything he damn well wants to. His first two albums, Geronimo’s Cadillac and Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir, are laced with themes of fundamentalist country music, but Murphey recognizes that country is a self-limiting form and is moving toward a more complex and innovative music.

He tries to limit himself to about 20 performances a year, partly because he questions the rock ritual: “It’s not worth one overdose and it’s not worth one person getting hurt. If that’s what rock and roll is, then let’s not have it anymore.” But Murphey has decided he would rather write songs than epic poems or novels, and he hopes to write them in Austin.

By coming back to Austin within a few months of each other, by attracting attention to Texas’ better qualities with their music, Murphey, Stevenson, Walker, and Frumholz have set rolling an excitement that could permanently alter the face of their chosen city. A booming music industry would offer obvious advantages to local pickers: They could record close to home, travel less, and commune with like-minded musicians. On the other hand, Murphey warns that “scenes have destroyed an awful lot of places.” But others believe they can sustain an Austin music boom and still escape the inner city blues. “If the hype gets too bad,” Frumholz says, all the pickers I know will lay back and hide.” Stevenson agrees: “Too many of us who’ve already gone through that stuff wouldn’t let it happen in Austin.” Perhaps so. Certainly Murphey, Frumholz, Walker and Stevenson have had enough experience with music business rip-offs to be on guard. But Murphey fears for the innocent: “I’d hate to see people with guitars on their backs suddenly showing up by the thousands. Because they’re gonna starve.”

Some fine artists already are. Rusty Weir, 29, living in Austin, tries to make a living off club appearances from Michigan to Texas. After ten years of that tiring, noisy life, Weir recently reflected during a gig at an Austin beer ’n boogie bar: “Hell, I started out in a beer joint.”

And a recording contract is not necessarily a panacea. The best of the Austinite first albums is Willis Alan Ramsey released in mid-1972; but Ramsey asked the recording company not to promote the record: “I don’t like advertising. Let’s just float it out there and see what happens.” Good as it was, the album fizzled. Dissatisfied with his new songs, Ramsey failed to deliver his second album and his recording contract was cancelled. He now ekes out a living from last year’s royalties and the occasional sale of one of his songs to more commercial artists.

The Austin players in worst financial shape are those who buck the country trend and continue to play straight rock and roll. Even the poorest new country bands can find gigs (Austinites seem to have forgotten that the noise of an unskilled country band is just godawful, regardless of the length of the steel player’s hair) but rockers have to struggle to make themselves heard. Clubs like the Soap Creek Saloon and Bevo’s provide them with occasional gigs, old stalwarts like Conqueroo and the Elevator are trying to make a go of it again, but there is an air of diminished expectations in Austin rock music.

Several bigger, more financially secure performers stand on the periphery of Austin music. Doug Sahm, the bluesey voice of the old Sir Douglas Quintet who resurfaced recently with country trappings and the aid of some superstar sidemen on a critically-praised album, drifts in and out of Austin, as does Kinky Friedman, a good country rocker with an unfortunate knack of offending people. Marc Benno of Leon Russell’s Asylum Choir fame has also moved in, and rumors float by, a dime a dozen, about more big-name immigrants. However, none of the big names has had much influence on Austin music as yet, with the exception of one.

A 37-year-old small-town Texan, Willie Nelson has a smile that would make Buddha nervous. It spreads across a face that bears lines of age and experience but still contains the warmth that makes Nelson so impressive onstage. For a couple of decades the Nashville music business kept Nelson writing when he wasn’t on the road pursuing an on-again, off-again career as a singing star, but in 1971 he decided his career could weather a move to Austin. He still plays the country bars and hangs out with Darrell Royal. But suddenly there’s a new, infrequently barbered Willie Nelson with a seasonal beard, drinking beer in the Armadillo beer garden and performing at McGovern rallies.

At a time when city-slickers envy country roots, this metamorphosis boosted Nelson’s career rather than hurt it. Atlantic signed Nelson earlier this year, promoting his Shotgun Willie album with a double-barrelled photo of the man in his most hirsute hippie splendor. They’ve switched his arrangements from Ray Price to Ray Charles—the result: a revitalized music. He’s the same old Willie, but veteran producer Jerry Wexler finally captured on wax the energy Nelson projects in person. Nelson plays Max’s Kansas City while in New York, and a Village Voice critic calls him the “best country artist in the land.” Willie Nelson is Austin’s first nationally-certified, Billboard-proclaimed superstar. This time, it seems, the prodigal son brought the fatted calf home with him.

If anyone is qualified to serve as high priest of Austin’s movement toward the big time, it’s the grinning, gentle rebel who made the music industry come to him on his own terms yet somehow remained the almost universally admired nice guy and artist. Willie Nelson has thus become a symbolic figure, the one man whose approach to life and music makes sense of Austin’s curious mix of freaks and rednecks, trepidation and ambition, naiveté and striving professionalism. And where symbolic heroes move, cults often follow.

But in the music business reputations are gauged in dollars and cents. In March 1972, with their eyes on Nashville, several Texans staged a counry music festival on a ranch west of Austin. Poor promotion made that event a financial disaster, but the few who attended enjoyed themselves immensely. A year later, the site near Dripping Springs was still available, and Nelson and a group of his more business-oriented friends decided to try it again on a manageable, one-day basis, running it professionally, charging reasonable prices, lining up the best of the new country breed—Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings, John Prine—along with good local performers. Just to keep things symbolic, Willie’s drummer Paul would get married onstage as the sun sank into the blue Texas hills. Business and pleasure combined.

Nelson hired Eddie Wilson’s Armadillos to promote the event. Wilson had his doubts, predicting “either a big success or a big mess,” but as the festival neared it became apparent Nelson had guessed right: Texans were primed for the honky tonk of their lives. Word got around that Bob Dylan and Leon Russell were on their way. Some attribute the rumor to Doug Sahm, who did not show. Bob Dylan did not show. Leon Russell did show, after a fashion: He spent the day sampling various labels of beer, grinning a lot, emceeing a little, and warding off starstruck groupies and journalists.

A beautiful Fourth of July dawn found Nelson onstage along with a blinking, greybearded drummer named Leon. But by noon the Texas sun turned into a persistent bitch, torturing 30,000 incoming automobile travellers logjammed on two converted cowpaths. Braver souls started hitching, walking, and cursing in hopes of hurrying things along. Hikers and drivers arrived anywhere from one to three hours after hitting the traffic jam—and all arrived thickly coated with white caliche dust from the un-oiled roads.

The crowd sprawled out of the natural canyon which faced the bandstand onto barely more shaded hillsides. They stood in long lines before moveable privies, waited for ice that never arrived. The organizers neglected health provisions too, and Austin Free Clinic personnel coped unthanked with everything from wine prostration to heat exhaustion. Meanwhile, everybody backstage had a pretty good time for a while. The best picking of the day reportedly went on inside the air-conditioned mobile homes of the privileged. But minute by minute, the backstage compound got uglier. A shouting, shoving brawl erupted between the music industry’s two most obnoxious elements: the flunkies and the hangers-on.

The longhaired security guards, lacking a foreman, were soon power-tripping, casually shoving females into the dirt. And both in the compound and on-stage, hangers-on resisted pleas to vacate by the sheer force of their numbers.

Security hands finally cleared most of the stage during Charlie Rich’s set, and with the sun getting lower and the day cooling off, things began to look better. And at last, as Kristofferson prepared to play, the sun went down.

Showco Productions of Dallas had contracted to provide the lighting, but it was a bad day for everyone. When a UPI cameraman protested that the stage lights were insufficient for filming, a Showco employee yelled, “In one minute I’m going to knock your eyes out with two super troopers.” In one minute the lighting improved all right, but when a Kristofferson protegé fed two strong bass notes through the amplifiers, every transformer in that part of Hays County blew, and Willie’s Picnic plunged into total darkness.

Hangers-on began to lurk like hyenas back onstage. When somebody finally produced a gasoline generator, an emcee pleaded for patience and a drunk deputy sheriff suggested that everybody get naked. As a large portion of the audience groped toward the parking lot somebody thought of plugging into a Winnebago, and the show, not so loud and much dimmer, got pathetically under way again. Tom T. Hall broke a guitar string, and following the lead of his Woodstock predecessors, threw his $300 instrument to the crowd. A fist-fight ensued. One artist or another played until 2:30 in the morning, and dawn found a panorama of garbage that would have filled Armadillo World Headquarters wall to wall, floor to ceiling. Nobody had thought to retain a refuse collector either. The adolescent Austin music industry had reached for maturity and fallen flat on its face.

Adolescent debacles are rarely fatal, and they’re usually instructional. The day after the Dripping Springs fiasco Eddie Wilson slammed his fist against a wall in anguish and humiliation, but he was already formulating thoughts on how to do it next time. He is no stranger to learning from experience. Skeptical observers pointed out that music industry professionals from New York, Nashville, and L.A. could have run the picnic more efficiently, but Wilson doesn’t want the pros around. He knows that with them will come the industry’s major pollutant: carpetbaggers. Already he has seen all kinds of hustlers floating through, “looking for a shuck and a jive.”

Wilson and his music business colleagues stress that any Austin music boom must remain localized. The creation of a music center in Austin would bring millions of dollars into the local economy, millions that would wind up in the pockets of Austin musicians, technicians, artists and publicists struggling to get by now. Even the environment would benefit. According to Wilson the music industry, unlike others that a growing Austin might attract, “doesn’t pollute and it doesn’t get in the way visually; about 50 million dollars could be put into the Austin music business and remain invisible.” The stage has been set very nicely, so why not continue? Thus the music businessmen proceed, caution thrown to the winds.

Within a week after Dripping Springs, Eddie Wilson returned to the Armadillo’s stage to emcee Texas’ first locally conceived, locally produced rock simulcast, speaking emotionally about the unique character and sparkling future of Austin’s music scene. As Wilson said, longhairs and goat ropers can co-exist at the Armadillo; but they also shot each other the finger at Dripping Springs. As Wilson said, Nashville is watching what’s happening in Austin; but the music business wears chameleon colors, and the “country-rock” boom may soon go the way of sitars and moogs. Hope springs eternal, but Billboard rules the air waves.

The rock & roll musician has replaced the cinematic actor as America’s number-one star. He is at the mercy of a mass-marketed culture which forces him to think like a businessman and throws him into the clutches of a possessive but fickle audience. The performers who forced Austin music to relax came to the hill country to save themselves and their art from such a culture. If Austin becomes the sort of music scene America has known previously, they will have to compromise some of their integrity or pull up stakes again. In late June, Mike Murphey took his shirt off and entertained another of those fine Armadillo crowds. At night’s end Murphey was beaming at the frantic crowd milling beneath him, and he left with the words, “I don’t know how long this can last, but I’m with you as long as it does.” We don’t know either. We hope Austin’s laid-back pickers can hold their unique fort, but that may be like wishing the boys of the Alamo luck against Santa Anna’s dusty legions.

- More About:

- Music

- Longreads

- Country Music

- Willie Nelson

- Jerry Jeff Walker

- Austin