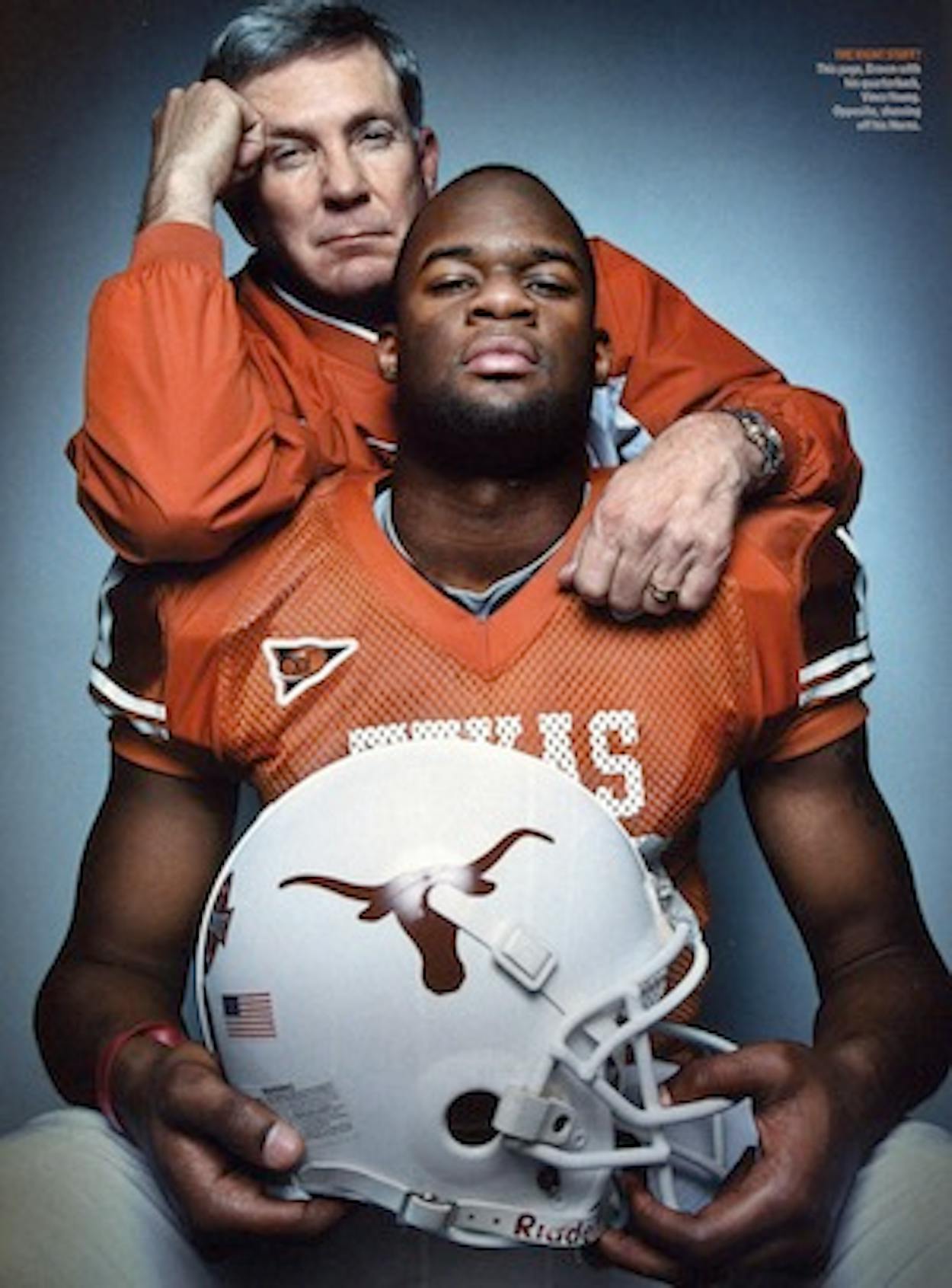

I LIKE HAPPY PEOPLE,” says Mack Brown, the head coach of the University of Texas football team. “I really do. And I like my staff, and I want positive people around. I don’t want negative people around these kids. I tell ’em, ‘If you don’t like it here, leave. If you stay, be upbeat, positive. I want you to have some fun.’” Brown has a warm, honest face, with friendly eyes. At 54, he is six feet tall and in good shape. He looks like what Opie Taylor might have looked like all grown up if Ron Howard had kept his hair. On this March day in his office, he is wearing khakis, loafers, a white sports shirt dotted with little burnt-orange Longhorns, and an optimistic smile about his team’s chances in 2005. But Brown is always optimistic. “This is the best coaching staff we’ve had,” he says. The high school coaches’ clinic he had put on earlier that month, he said then, was the “best clinic we’ve had.” Even though that winter’s recruiting class had failed to meet expectations, “really,” he said at the time, “that’s a good thing.” A word he often uses is “fun.” “This is a fun time,” he’ll say, or, as he said about his players at spring practice, “It is fun to coach and fun to watch them right now.”

Brown should be having fun. In his seven seasons at UT, he’s done almost every single thing right. He has won seventy games and taken the Horns to seven bowl games, winning four of them, including January’s thrilling Rose Bowl, where UT beat Michigan on a last-second field goal. Brown has the best winning percentage among Horns coaches since 1922; indeed, over the past nine years, no college football coach except Florida State’s Bobby Bowden has won more games than Brown. He has scored several top recruiting classes, bringing the country’s best talents into a clean, well-run program. And he’s brought back the fans, the alumni, and the boosters who had become disenchanted with almost two decades of Longhorns pigskin mediocrity. Ticket sales went from $8.3 million in 1997, the season before he arrived, to $20 million last year, a season that saw the football team net $37.5 million overall. Brown has even made Bevo hip. After years of being out of style, UT is now the number two university in the country in merchandising sales.

It’s been a long time since so many people outside Texas bought orange T-shirts or cared so much about the Horns. And around the Forty Acres, Brown gets the credit. “He’s the closest thing we’ve had to Darrell Royal since Darrell Royal,” says Houston lawyer Joe Jamail, one of UT’s biggest boosters. Athletics director DeLoss Dodds adds, “He’s unified our folks, and he’s put a new face on recruiting. And he’s done it with class.” To reward Brown, last year the administration paid him more than any other coach in the country—$3.6 million, a base salary of $2 million plus a $1.6 million gift for staying at the university. In December, UT gave him a raise, a ten-year contract worth a minimum of $26 million. Nobody begrudges Brown the money; he earns every penny. At least for 364 days and 21 hours a year.

It’s those three missing hours that drive the faithful crazy. Every October the Longhorns travel to Dallas for their biggest game of the year, the annual Red River Shootout with archenemy Oklahoma. But for the past five years, the Sooners and their coach, Bob Stoops, have humiliated the Horns, blowing them out (63—14 in 2000) and shutting them out (12—0 in 2004). Not only are the defeats soul-destroying, they keep UT from winning the Big 12 South Division and, ultimately, from getting to a national championship game. For some Horns fans, the streak, as well as Brown’s reputation for not being able to win other big games (he’s 3-10 versus top ten teams), stirs a deep worry. Maybe, this nagging thought goes, Brown isn’t the chosen one, the one who will lead them back to championship glory. Maybe he’s just a great recruiter, a great salesman, a charmer who goes after, in his words, “nice kids who graduate.” A great guy but not a great coach. Maybe he’s not tough enough, fiery enough. Maybe he’s too damn nice.

Brown, of course, has heard this before, and his reaction is just what fans have come to expect. “My first thought when I heard that,” he told me in his soft Tennessee accent, “was ‘What a great thing to say about somebody. “Too nice.”’ If that’s the worst thing anybody ever says about you when you go lay down to die, that’s probably pretty good.”

ON APRIL 2, the last day of the Horns’ spring practice season, under the shade of four sprawling oak trees on a worn patch of grass just east of Darrell K Royal—Texas Memorial Stadium, a bunch of fanatics gathered to drink beer, eat barbecue, and talk UT football. They were tailgaters, and they formed an island of orange in a sea of black asphalt, dozens of people wearing “Longhorns,” “Texas,” or “Rose Bowl Champions” T-shirts; their numbers would grow fivefold by the seven o’clock kickoff of the annual UT spring game. Meat smoked in a pit, and three large coolers held Bud Light, Coke, and water. Two Longhorns flags flew in the breeze, as if there were any doubt who was encamped here.

A parked white van had its back doors open, revealing a TV showing a DVD of the Rose Bowl game played just three months earlier. Diane Walters sat in a chair watching the game, while Jerry Clark tended the meat on the grill and James Lyle wandered among clusters of fans, drinking beer and chatting. On-screen, quarterback Vince Young threw short passes to his tight ends, and running back Cedric Benson pounded away at the line. Every time the camera cut to Brown on the sideline, he looked tense and worried, his face hard, his mouth turned down. He wasn’t having fun. Even after Young ran for a touchdown, making the score 7—0, Brown looked as if he were down 30 points. Walters looked on in admiration. “He’s the hardest-working coach in football,” she said.

The other fans shared her stubborn pride in Brown as a moral man in the violent, corrupt world of big-time college sports. “He has an open heart and embraces his coaches and players,” said Clark. “The players desire to please him.”

“When someone screws up at UT,” said Walters, “the coaches go over to the kid and explain what he did wrong and why. They’re teachers, not intimidators.”

“It’s not Mack Brown’s job to yell at those kids,” said Lyle.

“Brown made a conscious step to win,” said Clark, “but with great players who are good students. The great Miami teams—the word that comes to mind is ‘thug.’ You’ll never hear that term with UT and Mack Brown.”

As the game progressed, fans would gather around the TV every time a big play was imminent. Most of them involved Young. A touchdown pass to tight end David Thomas in the second quarter. A 60-yard touchdown run in the third. Young is, everyone here agreed, the best college athlete in the country. He may have a strange, almost girly throwing motion, but after two years, he’s the most accurate passer in UT history, and he has the ability to freestyle his way through even the best defenses. “Next season lives and dies with Vince Young,” said Walters. Young is the main reason the fans are excited about 2005, but they’re also thrilled about new co-defensive coordinator Gene Chizik, who last year led Auburn to one of the best defenses in the country. It’s the offense, especially offensive coordinator Greg Davis, that has everyone worried. “He reminds me of a dog that chases parked cars,” one of the tailgaters said. “He runs into one, falls down, gets back up. Runs into another, falls down, gets back up. How many times are you gonna do the same thing, especially in big games? Let’s go play OU and shrivel up like a ten-year-old boy’s testicles in cold water!” Everyone laughed. “We all agree,” Clark said, “that in big games, Texas plays not to lose, instead of to win.”

Early in the fourth quarter, UT was down 31—21 and had a third and goal on the Michigan 10. Walters announced, “Okay, ladies and gentlemen, this is the play.” The crowd gathered around. Young took the ball, scampered back 5 yards, somehow spun his six-foot-five frame to avoid a lineman, then slipped two more tackles and caromed into the end zone. “God,” someone said. “It’s just sick.”

Young later scrambled for another touchdown, Michigan got a couple of field goals, and UT finally got the ball back with three minutes to go, down 37—35. Young marched the team methodically down the field, and Texas lined up for the winning field goal. I asked a couple of men if they were nervous, even though they knew what happened next. “Yeah!” they answered simultaneously. “All right, all right, all right!” Walters announced, flashing a hook ’em sign. The center snapped, kicker Dusty Mangum swung his leg, and the ball, barely tipped, wobbled over the goalpost. Everyone erupted in cheers, hopping up and down and giving high fives. Clark sat back down again. “How sweet the wine,” he said.

The January victory was huge for both UT and Brown. Yet afterward, some fans still found reason to complain. UT had been ranked number six, they pointed out; Michigan was ranked number twelve. The Longhorns were supposed to win. Also, it wasn’t as though Brown had come up with some brilliant game plan; if any other college kid had been at quarterback, UT would have fallen apart. And if some Wolverine had gotten just one knuckle more on that kick, the Longhorn faithful would have wintered in despair.

But none of that mattered to the tailgaters. The Rose Bowl win had propelled Texas into 2005, the season in which many of them believe UT will beat OU (which graduated its Heisman-winning quarterback and many of its receivers and offensive linemen) and Mack Brown, the nicest guy in the meanest sport, will finally win the biggest game of all. “How many days until kickoff,” yelled Cody Norris, a late arrival. “One hundred and fifty-three? I’d rather chop off my big toe than wait that long.”

BROWN WAS HIRED away from the University of North Carolina in December 1997 for one reason: to bring a national championship back to Texas. He had a reputation as a “CEO coach,” and he knew it wasn’t enough to win on the field. Brown had to bring back the customers, improve the goodwill of the company. His to-do list looked something like this:

1. CALL COACH ROYAL.

The new coach, who was born and raised in Cookeville, Tennessee, knew all about Royal, the last coach to win a championship for Texas, in 1970. Brown’s father and grandfather were both high school football coaches, and they talked about the UT legend, who was in his heyday in the late sixties, when Brown was a star high school running back. When Brown was interviewed for the UT job, he asked Royal, who was part of the search committee, if he’d help him get the program back on its feet. Royal, who liked the confident, optimistic coach, said yes. He had been mostly ignored by his three successors, but Brown gave him an office and an open invitation to visit and accompany the team on road games. The new coach would even ask the old one to speak to the team. In return, Royal became Brown’s mentor, giving him wisdom: Football at Texas is every day, he said. You’re responsible for the way millions of Texans feel every day. It would be pressure like Brown had never felt. Royal also gave him comfort; both Brown’s father and grandfather had recently died, and Royal would become a father figure. He also gave him cover; Royal would become a major ally when things went sour.

2. REACH OUT TO FANS, ALUMNI, AND THE MEDIA.

The day after getting the job, Brown met with the media and more than two hundred die-hard members of the Longhorn nation at the Frank Erwin Center, where he fired up the crowd by talking about playing a bold, high-scoring offense and a swarming, aggressive defense. Longhorns fans had heard about Brown: He ran an honest program and his players graduated. He was both emotional and smart. He was a hugger, known to cry after losing games, and he was a winner: an offensive coordinator at OU in 1984 under Barry Switzer (the best he’d ever seen, the hated Sooner coach later said), a head coach at age 32 at Appalachian State, then Tulane, and then UNC, the basketball school that he took to 10-1 and number seven in the country, just before being hired at UT. After the Erwin Center pep talk, Brown hit the road, crossing the state and speaking to alums and fans at Longhorn Foundation meetings, telling stories and football anecdotes in the cadence of a politician; by football season he had given 93 speeches. The hungry Longhorn faithful packed the meetings and afterward met him, shook his hand, and were thrilled that he looked them in the eye and remembered their names.

3. MAKE THE PLAYERS FEEL COMFORTABLE.

At the first team meeting, Brown joked with the players to stop ogling his wife, Sally, and he talked about having fun. “He came off really well,” says former linebacker Anthony Hicks. “He struck us as different from [previous coach] John Mackovic—the way he would run the team. He was aggressive and had an open personality. With Brown, I thought, ‘This is gonna be fun.’” Brown did little things that meant a lot, like getting the team an air-conditioned bus for rides to the practice fields in the summer. He was, the athletes all agreed, a player’s coach. He wasn’t above fooling around with them, dropping down and doing push-ups, even dancing. And he was sincere. “He cares about you as an individual and as a player,” says former linebacker Dusty Renfro, who played at UT from 1995 through 1998. “He wanted to make sure everything going on in your life was okay. He always took your side first—against other students, the administration—until he found information to change his mind. A lot of coaches are not like that.” The player Brown needed the most that first season was running back Ricky Williams, who was contemplating leaving school early for the NFL. Brown persuaded him to stay for his senior year, and from that time on, he has not lost one player early to the pros.

4. BOND WITH HIGH SCHOOL COACHES.

Texas has more blue-chippers than any other state, and Royal advised Brown that he needed to connect with the men who coached those boys. Brown and his new staff set out to visit every one of the 1,200 high schools where kids suit up in pads—and then stayed in touch with them. He started a high school coaches’ clinic, where coaches could visit UT to learn how the big kids practice and play; it’s now second in size only to the Texas High School Coaches Association clinic, attracting more than one thousand coaches every March. Brown also invited the coaches to fall practices, which are usually off-limits to the rest of the world, and he gave them each a free pass to every home game. They came, they saw, they returned home excited about Brown, the UT facilities, and the Longhorns.

5. BRING BACK THE LETTERMEN.

Like Royal, former UT players felt underappreciated. Brown let them know they could visit his office anytime or come to any practice. “That hadn’t been done in recent years,” says Ted Koy, star running back and member of the class of ’69. “He told us UT has a rich football tradition and he wanted to cultivate it.” Brown threw himself into helping with the yearly lettermen’s golf tournament, and more and more former players began to show up. This April, 160 came, old-timers like T. Jones (class of ’59) and Koy and more-recent grads, like Hicks (’99). Most wore orange, and all had nothing but great things to say about Coach Brown. “He’s brought back the family feel,” says Hicks, “the orange blood, so people can say, ‘This is Texas.’”

6. RECRUIT AS THOUGH YOUR JOB DEPENDS ON IT.

Brown almost immediately started knocking on the doors of high school phenoms. Recruiting is all about persuading, and nobody persuades like Brown. “He could talk me into eating a ketchup popsicle,” said Bay City quarterback Beau Trahan, part of that first class of recruits in 1998. Brown routinely scored the country’s top prospects, such as New Jersey quarterback Chris Simms in 1998 and Midland running back Cedric Benson in 2000. “Coach Brown just makes you feel like you’ve been friends with him your whole life,” said Simms, now a quarterback with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers (Benson was the recent number one draft pick of the Chicago Bears). To lure players, Brown also set to work upgrading UT’s facilities. The 70,000-square-foot indoor space, a.k.a. the Bubble, was built. He remodeled the Moncrief-Neuhaus Athletics Center into a huge state-of-the-art facility. He installed a trophy room, where he encouraged visiting prospects to hold the Outlands or the Heismans of the past. He expanded the weight room. He took the kids down the hall past photos he’d put up: Longhorn All-Americans and academic All-Americans, great moments in UT history, and a wall of NFL helmets with the names of the Horns who had played for each team. He took the kids and their parents to the athletic facility’s academic center, with its 36 computers, and told them that UT spends more than any other university on counselors and tutors for its athletes. And, he can now say, it works. When the NCAA released its first-ever academic report cards in February, UT passed, scoring higher than OU.

Royal—check. Fans, alumni, and media—check. Players, coaches, lettermen, high school kids—check. By the start of Brown’s first season, his to-do list was done. That year the Horns went 9-3, with Williams running wild and winning the Heisman. Enthusiastic fans packed Memorial Stadium again, and by the time UT won the Cotton Bowl, Brown was a local hero. He’d go out to restaurants and people would stare or ask questions about the team or ask for autographs. Brown would politely answer and sign. After the season, his salary was increased to $1 million a year.

But his honeymoon with Texas fans lasted only until the 2000 OU game, when the Sooners crushed the Horns 63—14. Fans couldn’t understand why Brown alternated quarterbacks, going from the freshman Simms to junior Major Applewhite, who had been the Big 12 Co-Offensive Player of the Year in 1999. Brown apologized to fans, coaches, and players afterward, calling it the worst loss of his career. He was lambasted for indecisiveness and playing it safe. What good is a great recruiter, asked some critics, if he can’t coach those kids to win? Things didn’t get much better the next year, when he again juggled the two quarterbacks, starting Simms but eventually replacing him with Applewhite in the Big 12 championship game, which UT lost. Still, UT went 11-2 and wound up ranked number five, the first time that had happened since 1983. In 2002 the Horns again went 11-2 and wound up number six.

The 2003 season ended terribly, when heavily favored UT lost to Washington State in the Holiday Bowl. Brown panicked, critics said, yanking then-freshman Young for the less mobile Chance Mock against a team that was number one in the country in quarterback sacks. The loss gave more ammo to newspaper writers, talk radio callers, and angry posters on message boards such as the newly created firemackbrown.com: Yes, Brown was winning games against teams like North Texas. But he couldn’t beat OU, and he couldn’t win a conference championship, much less a national championship. He couldn’t even get to a Bowl Championship Series game.

BROWN’S UT OFFICE is a long way from the dank, cinder-block field houses of his youth. The room, with dark paneling and white carpet, is large and heavy with a sense of accomplishment. Everything is orderly, and every artifact of glory is in its place: Heisman, Doak Walker, and Rose Bowl trophies on the coffee table; pennants, plaques, and group photos of teams past on the wall. Brown sat with his back to a huge window, through which you could see the grand expanse of Memorial Stadium. I asked him how he saw his job as head coach. “I’m in charge of a huge business with one hundred thirty student athletes, plus another forty-seven people who work in football in the building. And then there’s your investment with the media, your fan support, your faculty. It does get enormous. You’ve got to be able to walk out of Joe Jamail’s office with a coat and tie on and go into a high school with blue jeans that’s maybe five miles away and then go into a sixteen-year-old’s home that night. And handle all three situations well.”

Indeed, the best college football coaches are multitasking geniuses: part motivator, part psychologist, part salesman, and part football brainiac. Brown was born and raised for the role. His father, Melvin Brown, was the tougher of his coaching influences. Once, as a Little Leaguer, Mack took a called third strike, and Melvin, watching with other parents, yanked him from the game. His grandfather Eddie “Jelly” Watson was gentler yet still won more games than any other high school coach in Middle Tennessee history. Mack was brought up in a disciplined Church of Christ household, went to American Legion Boys State, sang in a choir, and played sports. He loved football most of all and got a scholarship to Vanderbilt, then transferred to Florida State, where, after his fifth knee operation, he gave up playing and began coaching. By the time he got to UNC, he had developed many of the things that make him the coach he is today, such as good-old-boy charm, an openness to others’ ideas, and the ability to sell his own. He likes to talk, often quoting Royal (“As Coach Royal says, ‘You don’t ever want to sit in the shade’”) and spinning football anecdotes and aphorisms, many of which he’s told before.

I asked him about the perception that he is a CEO coach. “I would think it’s a compliment if it means I’m in charge of a corporation that has a huge budget and is a great source of revenue and attention for the university,” he said. “If it means I don’t do anything but delegate, I’d say it’s an insult.” Brown acknowledges that he spends a lot of time trying to figure out the right thing to do, collaborating with the people whose opinions he trusts the most—his assistants—then making the final decision. “Even my wife tells me I listen too much. I listen to a lot of people’s opinions because I want to get their ideas. I’m gonna get all of those ideas because I feel I can make the decision a lot better if I know how our players and coaches feel.” When Brown arrived at UT, he found that his way was different from his predecessor’s. “Mackovic was a micromanager,” says former center Matt Anderson, who played for both men. “He’d watch the offense, critiquing everything, talking with players and coaches during and after practice. Brown lets his assistants coach. They’re the ones who interact with the players every day. I’d much rather have the offensive line coach talking to me on the field.” This doesn’t mean Brown won’t occasionally get down in the trenches with his players; at any given practice you will see him yelling, gesturing, and talking to his players face-to-face. “He’s all about execution,” says Hicks. “Run, block, catch, hit the runner. He makes the game simple.”

On the field and off, nobody works harder. Brown gets to the office at seven and sometimes doesn’t leave until seven—and then he often has to attend some UT function. He puts his players through intense, regimented workouts, but he also treats them with respect. They say his door is always open, and when they come in, he asks them about their family or school. “He always talks about academics and the importance of graduating,” says Rodrigue Wright, a senior lineman who could have been a first-round NFL pick this year but chose to stay and play his last year for Brown. “He always says that even if you do make the NFL, there’s only two or three years in the league on average, and you have to have something to do afterward.” Many of his players grew up in single-parent homes, and Brown, the son of a coach, becomes something of a father figure, often taking them to his home, where Sally will cook them dinner (the couple’s four children are grown and gone). “We look up to him,” says Young. “He makes us be better men—shows us how to treat our moms and girlfriends—when we see how he is with his wife. He shows you how to respect the adults around you.”

Brown wants his players to be happy, and he wants them to feel good about themselves. “We never have ‘weaknesses,’” he told me. “We have ‘areas of concern.’” He sits down with each player at the end of the year and talks about what just happened and what will happen next. He seems to be at his best one-on-one, as he showed near the end of the Rose Bowl. Just before the final field goal attempt, Michigan called a second time-out to try to ice Longhorns kicker Mangum, who trotted over to the sideline to talk to Brown. The TV cameras caught the brief conversation between the 21-year-old walk-on with more pressure on him than any Longhorn in modern history and his head coach, who had looked so intense and uptight throughout the game. With millions watching and their professional and personal lives depending on it, Brown laughed and joked and Mangum smiled and relaxed. Then Mangum went back out and kicked a football 111 feet through a space no wider than a Cadillac.

A UT ALUM I KNOW has season tickets to Longhorns football games and last year took his entire family to Pasadena for the Rose Bowl. But he’s stopped driving to Dallas for the Red River Shootout. He just can’t bear the pain anymore, on the field—189—54 over the past five years—or off, where Sooners fans young and old taunt him and his family. Jeff Ward, an All-American placekicker at UT in the eighties and now an Austin talk radio host, says, “A fan knows that something is going on. 63—14. Something’s wrong. Something seems to paralyze the Longhorns on that day.”

Depending on whom you ask, that something is either Mack Brown or OU coach Bob Stoops. Stoops is a defensive whiz who has devised elaborate schemes that confuse the Horns’ offenses (and almost everyone else’s) while he has allowed his backs to run wild. He’s brash and arrogant. He gambles. In 2001, OU had a 7—3 lead and a fourth down on UT’s 24-yard line with two minutes left. The Sooners lined up for a field goal, but Stoops had his kicker pooch a short punt, which put the ball inside the 5. On the Horns’ next play, Stoops ordered a blitz, the safety hit Simms as he threw, and the ball was intercepted for a touchdown. Final: 14—3. In 2002, OU, down by 11, had a fourth and four on the UT 8 with 22 seconds left in the first half. Instead of taking the sure 3 points, Stoops went for a touchdown, got it, then went for the 2-point conversion and got it too. Now he was down by only 3. UT got the ball back at midfield with 5 seconds left, enough time for one long heave into the end zone. But the Horns played it safe and ran out the clock. The Sooners went into the locker room with momentum and won 35—24.

“When I hear Stoops,” says my UT alum friend, “I hear enthusiasm. OU has cockiness and arrogance. It’s real. Right now, OU expects to win. We hope to.” Stoops’s players know their coach is 12-3 against top ten teams. They know he’ll take risks when he has to. Dean Blevins, a former Sooners quarterback and the sports director for KWTV in Oklahoma City, says, “Stoops knows that the key thing is, the players have to trust him. They have to believe in him, especially at crunch time. The players will see a coach’s body language and know his track record at crunch time. No excuses, an aggressive approach, and firm decisions. Stoops is the anti-politician.”

Brown, meanwhile, has a woeful record against top ten teams. Critics say that’s because he plays it safe. Last year’s 12—0 shutout, the first suffered by UT in 24 years, was a blueprint for fans’ frustrations: a timid team, so nervous about making mistakes that it didn’t go for it. The offensive game plan, used to great effect in September against the University of North Texas and Rice, was simple: Give the ball to Benson and throw short passes, mostly to the tight ends. It was also predictable. Young wasn’t throwing the ball downfield, so OU, which had a porous defense that was later torched by the University of Southern California in the national championship game, was able to put as many as nine men at the line, stuffing Benson and harassing and confusing Young to his worst game ever; he looked, some observers thought, as if he hadn’t had any coaching. The receivers were too young and green to depend on, said Brown and offensive coordinator Davis later, though there had been plenty of practices and games against lesser teams to get them some experience. When Benson won the Doak Walker award in February, he said publicly what many Horns fans have said privately about the OU game. “The coaches coach more of not to lose instead of trying to win,” he said, adding that they need to “come up with a good game plan.”

UT fans blame Davis, even though, in several of his years at UT, the offense has set yardage and scoring records. The coordinator is 54 and looks like a friendly banker, with a soft face and bifocals. He is, Brown says, an easy target: “Every school of this magnitude has an offensive coordinator who ninety percent of the fans are mad at. Every time a team loses, fans want the offensive coordinator fired. It’s pretty predictable. The reason Greg has drawn so much criticism is we haven’t scored points against OU. We haven’t beaten OU.” Brown, as the head coach, knows he must ultimately take responsibility for the offense. And the losing streak. “No doubt about it, the five losses to OU have been the negative thing we’ve done. The seed of any criticism of us comes from that game, and that’s fair. It’s the only thing keeping us from winning the national championship.”

It’s also costing them top recruits. In the stands at the 2003 65—13 horror was a kid from Palestine named Adrian Peterson, the best high school running back in the country, a Longhorns fan who had a poster of Ricky Williams in his bedroom. He hadn’t been sure where he was going to college, but this game made up his mind. He chose OU, he said later, because the Sooners did a better job of developing players. He added, “One thing that has always bothered me about Texas is they can’t win the big game. I like the odds with Oklahoma for winning a national championship.” In last year’s Red River Shootout, the Sooners freshman ran for an astounding 225 yards. Grand Prairie’s Rhett Bomar, the best high school quarterback prospect in the country, also chose OU in the wake of the 2003 game. When he signed, he said how, in one meeting with Brown, the coach “wouldn’t stop hugging me. He was such a nice guy. But in the end that stuff didn’t make too much difference.” What did matter was that OU and Bob Stoops seemed to be more serious about winning. Blevins says, “The perception of OU fans is that if Bob and Mack brushed against each other in a hallway, Bob would turn around with his fists up and Mack would turn around and say, ‘Excuse me.’ Mack is the kind of guy you meet and think within two minutes, ‘What a great guy.’ But sometimes you can be too nice.”

Every October, before the OU game, stories appear in the press and on talk radio about how Brown is on the hot seat, that he or Davis will be fired if UT loses again. And every year OU wins and nothing happens. Boosters like Jamail, brass like Dodds, and patriarchs like Royal say that the program is in the best shape it’s ever been. It’s winning, the blue-chippers are coming, the fans are back and so is the money. According to Dodds, before Brown’s debut season, UT had rented half of its 14 luxury suites; now there are 66 (at up to $88,000 a year each), and there are two hundred names on the waiting list. Boosters gave $6.6 million to the Longhorn Foundation in 1997; last year they gave $18 million, and most of that came from die-hard football fans. “Mack is not on the hot seat and he’s never going to be on it,” says Dodds. “I have a tendency to dwell on the kids he has and the program he runs.” Yes, it’s important to beat OU, the optimists say, but the game has always run in cycles; many point to Nebraska’s Tom Osborne, who lost to OU for five straight years, then turned everything around and went on to win three national championships in the nineties.

Jamail just laughs at the idea of a hot seat: “He’s on such a hot seat we gave him a raise.” The $26 million contract was approved before the Rose Bowl victory, without Brown’s ever even winning the Big 12, and shows how much the UT bigwigs love him and, maybe, how little it matters whether the Horns win a championship under Brown. If Brown goes 10-1 for the next ten years, I asked Dodds, and that “one” is OU, is that just the way it is?

“That’s just the way it is,” he said.

AT AROUND SIX-THIRTY, the tailgaters began wandering over to the stadium for the spring game. All of a sudden it felt like fall. Forty thousand fans, mostly in orange, cheered as the players, in full uniforms, blasted through a cloud of dry ice. The Longhorns cheerleaders led the crowd in “Texas Fight!” and in the bleachers, five shirtless men stood next to one another, with the letters T, E, X , A, and S painted on their chests, bellowing in the cool 55-degree air. Boosters sat in their luxury suites up high. Lettermen such as Derrick Johnson, a first-round pick in the recent NFL draft, stood in the grass behind the end zone.

In the hour-long scrimmage, Young threw some beautiful passes, tailback Ramonce Taylor ran back a kick for a touchdown, and tight end David Thomas made a spectacular leaping catch and somersault. The crowd roared. Brown stayed on the field for most of the game, the only coach out there (everyone else watched from the sidelines), standing about twenty feet behind Young. While Davis and his staff sent in plays and Gene Chizik and his people sent in adjustments and schemes, the head coach clapped, shouted encouragement, and blew his whistle. Sometimes he gave his players advice man-to-man, such as when he approached wide receiver Limas Sweed, talking to him and rolling his hands forward like a paddle wheel. He patted Young on the butt and once put his arm around his waist as they listened to something being shouted from the sideline. At the end, he gathered his players, said a few words, and they turned to face the crowd, holding up hook ’em signs as the band struck up the opening bars of the orangebloods’ peculiar anthem: “The eyes of Texas are upon you/All the livelong day./The eyes of Texas are upon you/You cannot get away.”

A few days before the game, Brown admitted that he didn’t realize when he was hired in 1997 just how intense the scrutiny would be. He didn’t realize that “every day” really meant every day. It took time, he said, but he learned to deal with it. His skin got thicker. He realized it wasn’t about him; it was about the office he occupied. All he could do was his best, and when in doubt, he’d do what he felt was right, no matter how long it took to figure that out. If Brown has a mantra, he told me, it’s this: “Stay fair to yourself.” When I asked what he meant by that, he finally dropped the familiar quotes, anecdotes, and lines that sounded like they’d been used hundreds of times in front of thousands of boosters. “I didn’t know for a long time who I was,” he said, “and I didn’t know that I didn’t know who I was, but I was very uncomfortable at times because I kept fighting this something to prove to myself and everybody else I could do whatever this was. I wasn’t sure I could do it. I still don’t know for sure where all that comes from. If I sat down with a psychiatrist, he might say, ‘Your dad jumped you as a Little League baseball player, so you had to prove it to him.’ I don’t know.”

He paused, unsure for a moment where to turn. Then, quickly, he said, “But over the last—probably since we’ve been at Texas, really, I’ve been having more fun than I’ve ever had in my life.”

- More About:

- Sports

- College Football

- Mack Brown

- Austin