I grew up in the capital of the celebrity world, Los Angeles, where the sun rose to shine on us, not only me, even if it seemed so when I looked up; where ocean waves, not that far away when I ditched school and hitchhiked, lapped the shores like sweet, romantic kisses; where the blackened nights were white-lined boulevards full of starry headlights cruising low and slow, checking for the good and the bad, left and right more important than up ahead. I grew up where “cool” began, where music that mattered came to make it, the dip and sway stopping only when I was asleep; and where movies and their really important screens were actually big and curtained. All this was mine. This glam and glory spilled onto me and the hood I came up in, where I met the best-looking girls, I was in the baddest rides, and I was up against the ugliest, most dangerous dudes, who I could take if . . . if it weren’t for the fact that that L.A. was, maybe, as lasting as a movie-star sighting, a dreamland that had little to do with my life.

There are lots of L.A.’s, and mine was really a neighborhood that was cut through for the newest freeway, meaning not just cheap, dispensable land and people, but story. The heroic fable that ran in my head was one that warped significantly from larger facts, and only incidentally overlapped with the name of the city. When the truth penetrated, it was worse than being the earth and finding out the sun wasn’t swooning around it. I was, at most, a fleck of dust on this planet that was but a fleck of dust in the huge sky, and I realized that, as L.A. goes, accuracy aside, my story wasn’t of much unique interest either. We’ve all heard that perennial who am I? I began with where, which came with a how, as in, What kind of mess did I get myself into? My East L.A. dad, with his German roots, lived more like a cliché Mexican, 49 years at one job beginning at age 13, interrupted only once, by the Marine Corps, until he got laid off in his sixties. I grew up with my mom, who was born in Mexico but was nobody’s stereotype but for the drinking one. Single, she wanted to dress for a Parisian nightlife.

Brush aside lots of landlocked, unimpressive jobs that came and went lots more often than my drives between L.A. and El Paso, toss broken lineage issues that were my familial inheritance, and fast-forward to the mind’s homing instinct: jusat say I began by researching this large where through its big stories. I climbed the stacks for the too-faraway, the Naipaul from Trinidad, the Achebe from Nigeria, of course the Russian, German, and French (Dostoyevsky, Hesse, Camus)—no British for me, that language barrier too great—and then I went south to Fuentes in Mexico City, Vargas Llosa in Lima, García Márquez in Macondo. I wanted to be Beckett, old, wise, funny. I lived with Zhuang Zhou in China. Rulfo’s scorched earth altered my reading DNA, made me there and farther away at the same time. I finally started looking around nearer. I read Wright’s leftie Chicago, Kerouac’s New York to San Francisco and back, and Kesey’s fierce rivers, giant trees Oregon. I read L.A.: Bukowski—I wasn’t a drunk and didn’t want to get that ugly. Fante—sorry, dude, you’re good, but I have problems with your Mexican-gal BS. In El Paso I got closer still—Mariano Azuela, John Rechy, Ricardo Sánchez—but I wasn’t a Mexican national, I wasn’t gay, I’d never been a pachuco or in the joint.

I was living in an El Paso YMCA, financially zeroed, in 1977. That’s where I was exactly. Whatever the cause, I was the closest to “home” I’d gotten. It was like I was smelling the first musky wisp of desert rain, and I needed the rain. My girlfriend (who would later become my wife) had given up on me and moved back to Eagle Pass. She took a job at Crystal City High School. “Cristal,” in the Spanish pronunciation as it’s known by raza, was the source and beginning of the Chicano movement in Texas, starting in the late sixties. And there my girlfriend had found a book in the library, and she . . . though I still have it today, let’s say she checked it out for me. It was Estampas del valle y otras obras, and it was by the author Rolando R. Hinojosa-S, a name so convoluted it seemed more from a Borges short story.* A bilingual text, on the surface it was as it stated it was: “sketches,” or vignettes, of the Valley, which is to say the Rio Grande Valley, far closer than Argentina. It was in this book, by this writer, Rolando Hinojosa, that I found my lost where.

* His full name is Rolando R. Hinojosa-Smith. His last name goes with the usage common in the Spanish and Latin American tradition, with father’s last name first and then the mother’s maiden name. The hyphen is a North Americanism. It is ordinary, especially in Latin America, to simplify names to first name and father’s last. Thus, Rolando Hinojosa is what is used on all of his books post-Estampas and is how he is referred to by all who write about his work or know him personally.

How can a person—a man whose internal demand was to become a writer—born a few handfuls of urban miles from the Pacific Ocean find “home” in a rural community one or two handfuls of ranch miles from the river that is the Texas border between the United States and Mexico? In college, back in the day, I was lucky enough to go to events that brought César Chávez to speak. I loved going, but I felt as connected to the farmworkers’ movement as a high-rise ironworker with a spud wrench in a field of artichokes. I really had no idea how broccoli or carrots grew or where they came from but a supermarket—and who ate vegetables not already in cans? I was also around to see performances (later, not original) of the agitprop plays, the actos, written by Luis Valdez and his Teatro Campesino. As traveling tent theater, they were great and huge fun. Though the characters, all recognizable, were purposely exaggerated figures I knew well—suckered mexicanos, sleazy used-car salesmen and bosses, sellouts and thieves—they were not city enough for me. What I did recognize were Chicanas and Chicanos who could act and support a poor worker’s cause.

In Américo Paredes’s exquisite classic With His Pistol in His Hand, a defense of Texas Mexican history was brilliantly won—and the Anglo heroes of Texas, the Texas Rangers, weren’t so John Wayne tall or noble when it came to the treatment of raza. And besides the injustice based on their ignorant misunderstanding of horse terminology, Tejano Gregorio Cortez, the wrongly accused hero, could outride the hell out of them, leading to a ballad documenting his story and the culture’s pride.

Though Valdez and Paredes produced works that were paeans to Mexican Americans and their culture, and both writers (not to imply there weren’t others) became models for activist writing, the focus of each was what the people were up against to survive. Yet in Hinojosa’s world—his characters living in the Rio Grande Valley, what in his later books he would name more specifically Klail City, within the county called Belken—another, seemingly simple assumption became the setup for his fictional land and its residents.

In the Valley, in this Valley covered by ranches and towns, there are families in hiding. But make no mistake, they’re not doing it out of shame. They’re hiding out because they know who they are.

—Cipriano Villegas Malacara, 1855–1933

Senator, when one of those Valley Mexicans says yesterday, he probably doesn’t mean “yesterday” as such. Like as not, he’s most likely talking about 1850 or 1750, even. It’s hard to say; I can’t

understand ’em myself, half the time.

—Captain Rufus T. Klail, 1850–1912

Permit me to adjust and expand on what the deceased character Mr. Villegas Malacara had to say: those unashamed families, though hidden from view from the outside looking in, are clearly not in hiding. From the ground, from inside, they are far from unseen by anyone who’s there. This is what the entirety of Hinojosa’s writing, from Estampas onward, assumes and then proceeds to make clear to the smallest conversational detail. That the culture and community exists and knows it has from at least 1750 was not what was new here either. What was new, startlingly, was that Hinojosa, paying no attention to the dominant culture beyond, taking that for granted in the same manner of the residents of his fictional city, says this: it is there now too, still; it didn’t and doesn’t stop existing when readers look away, or when a searchlight dims on those issues and struggles, large and small, national and regional, criminal and political. Belken County is as autonomous and singular as Texas itself, no more or less dependent than any other small country, most unavoidably the “counties” in the north. Not to say that Klail goes unaffected; just that its history, its story, is not simply what exists in connection to whatever the current moment is with the powerful Anglo culture in the nation both call home.

What I saw in Hinojosa’s Estampas wasn’t my own family tree, except for what was just like it. What I saw in his land wasn’t like mine whatsoever, except it was the closest I’d encountered to what was. And I’d never seen it anywhere else. His neighborhood, rural Belken County, wasn’t much like the city streets I grew up on, but, especially as a writer, it was the first time I’d ever seen people where I was then (and now) and where I’d come from, the same as where he was. Yes, I’m saying Los Angeles and El Paso—and Corpus Christi, San Antonio, McAllen, Brownsville, Laredo, Eagle Pass, Del Rio, Albuquerque, Las Cruces, Denver, Tucson, Phoenix, Santa Ana, Riverside—were in the same county his residents lived and had lived. And here is what, for me, was most important: his characters confirmed an existence of these people as I found them—hidden in plain sight, unknown everywhere, yet seen everywhere anyone in the American Southwest looked.

In L.A., as in El Paso, as in Klail, the most common people have long family histories in the United States. They are working people, though the jobs are ordinary ones we know every day and, like the people themselves, are taken for granted and ignored. They work in stores as salespeople and offices as clerks and secretaries, in pharmacies and grocery stores, outdoors on soil or on rangeland. They are butchers and seamstresses, business owners and government employees, or at buildings making them or repairing them; they are cops and those who avoid the law. A few go to college if and when they can, many don’t, and some don’t finish high school. They have babies and brothers and sisters. They went to war and came back fine or less than, or didn’t. They’ve lived, and they’ve died. Sometimes they drink too much beer. They’ve married and divorced and had children who had children. They talk to each other a lot, or a lot about each other. Many know each other’s families and histories. And here’s this, above all this: like the bilingual book Estampas** itself, these are a people who speak two languages at once. Some are better at one than the other, some equally good in the two, but all listen and deal in both. The naive might want to say they are in two cultures. But this community is one, undivided, uniquely on this side of the border, going on, year upon year, utterly on its own. That it does so unseen in the United States of America . . . bueno, that’s how it is, how it’s always been, ni modo.

** It has to be said that Hinojosa’s Spanish, from its Castellano to Tejano, is not just perfect but beautifully composed on the page. Both high and low, formal and colloquial, his characters speak it as it is heard and used. Which is to say, not always in grammar books. Only later did Hinojosa take on the task of translating himself too, rewriting the pages for the English-language versions. The earlier translations not by him, in a corny drawl and sanitized as if by an overly cautious school marm, sometimes make for awkward reading.

Mexican American people come from a well-known region of the country, and yet somehow they are the very least recognized in it. Let me divide the continental United States into five areas: the Northeast, the Midwest, and the Northwest make up the northern half. In the southern half we have, on the right, the South. There we reckon with a huge area of America’s history, the source of the Civil War. Two sets of people live there. They are black, and they are white. Much aware of each other historically, even now African Americans would see the South’s history as African American, with heroes and martyrs of the two hundred years of racial division that put them there. Anglo Americans, on the other hand, still see a past that is predominantly about themselves, the pride and shame of the history of the South, the changes they were forced to accept. Yet both are extremely aware of each other and accept that this is what defines them. To all and any, that is a region of both black and white.

A similar bifurcation might be said of the Southwest region, what was historically New Spain and later Mexico until, through wars and annexation, it was decreed that its residents were citizens of the United States. Naturally there would be brown people, those of Mexican descent, and there would be white people, those who came to the hungrily expanding U.S. And yet, when Americans think of the Southwest—the southern half of California, Arizona, New Mexico; the southern regions of Nevada and Colorado and across half of Texas; down to the border from Chula Vista–Tijuana to Brownsville-Matamoros—what does anyone hear of Mexican American history and culture that isn’t only an Anglicized version of it? Better said, how many people, when they think of the Southwest, naturally think of Mexican Americans living in it? Instead of a brown-and-white culture, it is a blank-and-white one.

Not to say that the blank isn’t filled. There are mounds of stereotypes and caricatures to choose from, clichés as glaring as gapped-teeth, bandoliered bandidos; mustachioed mice with sombreros de charro; and hoarse Chihuahuas selling chain-food tacos. Even now, in El Paso, a business group from outside the city named its new Triple-A baseball team the Chihuahuas. Though not because of little old city ladies who love them, nor did that patronizing name occur to the owners from their deep knowledge of the dog’s non-cartoon origin, simply that it seemed to them as well-established cute and harmless—as ethnically recognizable as a movie Mexican accent—and not strong or fierce for the MexAm city. Imagine what could be picked for a team in Birmingham, Alabama, or for Chinatown, in San Francisco. Mexican Americans have been powerless (read: too poor) to fight being treated as so insignificant and lesser-than in virtually every category. Even the current word “Latino” has come with a marginalization that proportionally elevates the East Coast Latino—Cuban, Dominican, and Puerto Rican—to the MexAm, despite centuries in the American Southwest, despite the fact that inside the demographic it is two to one. In the West, that new voting demographic is booming. Yet when the news media question each group, what is the subject for our Belken County residents? Immigration.

Recently the LBJ Presidential Library, in Austin, celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Four presidents came to speak. On the first day of the conference, Julián Castro, the mayor of San Antonio, and Antonio Villaraigosa, the former mayor of Los Angeles, had originally been invited to speak on a panel about immigration. Both born and raised in the United States, these Belken County Chicanos had become experts on the topic. The implicit understanding? Always recent immigrants, Mexican Americans are never really from here.

The idea that Mexican Americans are foreigners, not long-residing American citizens of American soil, is not in the realm of consideration in the pages of Hinojosa. Citizens of Klail might discuss relatives in Mexico, but only in the same fashion that other Texans elsewhere might relatives in Louisiana or Kentucky. People in the Valley often talk about San Antonio and Austin, the big cities to the north. Two major characters in Hinojosa’s work, Jehú Malacara and Rafa Buenrostro, cousins, are each veterans of the Korean War, have gone to college at the University of Texas at Austin, and have returned to the Valley to engage in its business and city politics. Of course, they are aware of outside forces, the monied, land-grabbing Anglo Texans who want as much as they can, and then later, the drug-monied Mexican nationals who are a new source of Klail City trouble. All this takes up Hinojosa’s fiction, along with the domestic travails within—Rafa marrying into a white family; Jehú, a banker working where that money and power is, marrying Becky Escobar, née Caldwell, who will divorce the jerk Ira Escobar, relearn her lost Spanish, and let the strong, worldly Viola Barragán mentor her . . . and so on, sagas known too well in homes in L.A. and El Paso and all the rest of the Belken County cities of the United States.

Like the stories of these characters, tales such as these are unheard of or ignored outside the county lines. And so it is in the marketplace of literature in its native country. Aside from essayist Richard Rodriguez (beginning with his Hunger for Memory), I cannot think of a Mexican American who has bypassed the very smallest press markets before a rise to national stature. Rudolfo Anaya and his Bless Me, Ultima was first published by Quinto Sol Publications, in Berkeley, and Sandra Cisneros’s House on Mango Street was first published by Houston’s Arte Público Press; both these writers and their books came to national prominence, not by the usual acclaim of mainstream books and critics but by their overwhelming popularity in classrooms, from elementary to high school and then in college and university ethnic studies courses, where there is a natural demand for material that personally involves students—the goal of all education in the humanities. There is a huge brown demographic growing in the West, in this next America. Yet stories—fiction, nonfiction, poetry—about the residents of Belken are still seldom seen in mainstream books or magazines, virtually never taught in any mainstream courses in American literature, seldom even in Texas or Southwestern lit courses. Though the past few years have opened the heavy, creaky doors of the vaults, this not-foreign life from Belken County has continued to be little seen and little acknowledged.

From Estampas, first published in 1973 at Quinto Sol, to where he is now, fourteen volumes later, the vast majority with Arte Público, all of Hinojosa’s work has appeared in small presses. He has received little national attention. And yet, hidden in plain sight much like those in Klail, he does not care. Hinojosa will tell you he did not get into this work thinking it would ching-ching him to those bright lights and that big city known as New York. When I heard this March that he’d been honored with a lifetime achievement award from the NBCC and wrote him, late, to congratulate him for it, his early-morning reply was his usual style, elegant and quirky both, both good morning casual and gracias with sincerity. But in the afternoon came another, in a kind of email whisper: “Una pequeña molestia. What do the initials stand for?” He later said he was joking, but I am certain many reading this story wondered the same. And why would they, or he, know? The National Book Critics Circle—the NBCC—gives its Ivan Sandrof Lifetime Achievement Award only to book culture institutions as well-known, and often popularly obscure, as the Library of America, the PEN American Center, and Dalkey Archive Press, to people whose names are equal to institutions of literature, such as William Maxwell, Leslie Fiedler, Pauline Kael, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Studs Terkel, and Joyce Carol Oates. Hinojosa may not have known what the letters stood for, but I bet no one from Belken County, so far from the center of a publishing world, has heard of any of its best-known honorees.

I love the memory of my first visit with Rolando Hinojosa, in 1988. It was probably also my first time on the UT campus not as one of the unemployed (years earlier I had been trying to get a carpenter’s job working on the student union). I knocked on his office door, which was already a crack open. He swiveled around as I came in, then swiveled again to a mini-refrigerator he kept on a file cabinet and offered me a drink. It was scorching outside, though not so much in Parlin Hall. His office was admirably overstuffed with shelved books and teetering piles of ones not put away—for me a writer cliché I aspired to. I sat. Like goodbyes, I hate hellos. So I fumbled, went to the obvious: “Who’s your favorite Chicano writer?” He didn’t blink. He swung to his nearest book wall and drew out a Heinrich Böll. I cracked up. I knew we’d get along.

As I tell him this memory, twenty-plus years later, I mention not remembering which Böll it was.

“Group Portrait With Lady,” he quickly says. That makes me smile, new, all over again.

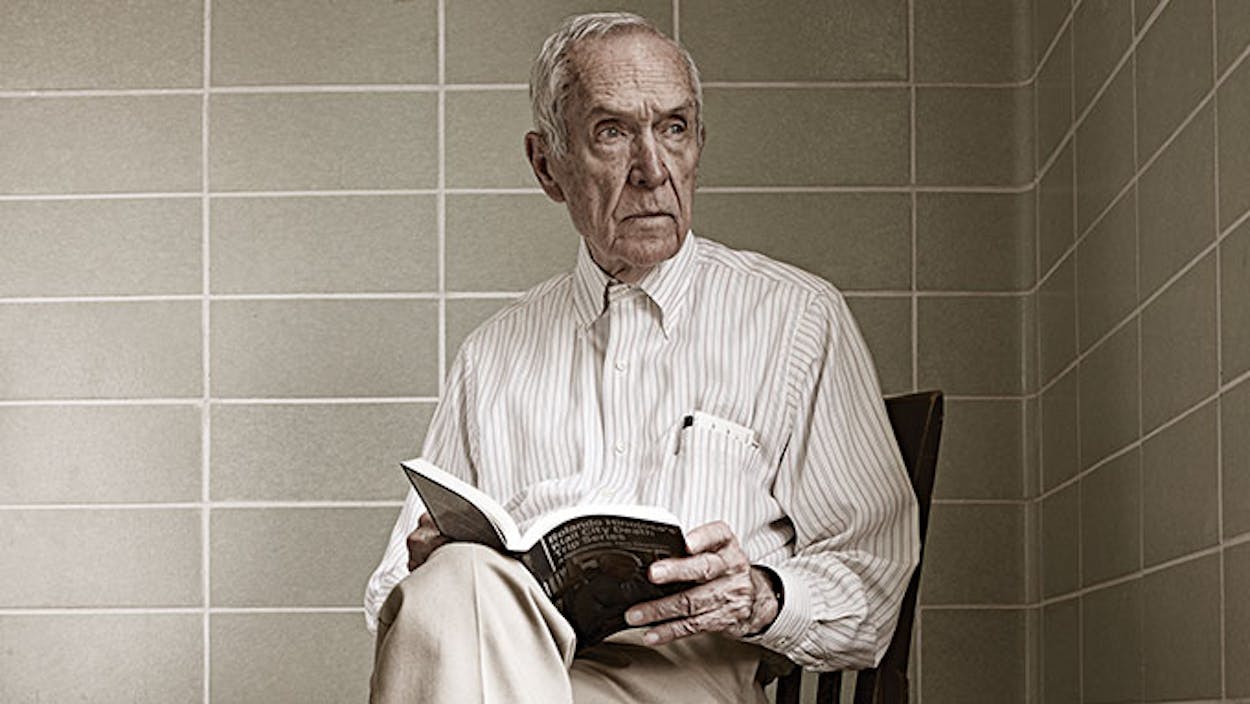

It’s the last days of the spring semester at UT, and Professor Hinojosa, now 85, who has been caught up in grading his finals, makes time for us to have lunch. I come with really only one question, about that homing instinct. I knew it had nothing to do with him, his life story, his fiction, or his award. The whole point of this essay is that he’s always had that answer.

Where he actually lives now is near the MoPac highway in an older North Austin complex named after a region in France, its sign done up in flamboyant calligraphy. Not yet “hotter than Texas,” there are tornado worries to the north of the state. A light mist smears the windshield. I’ve driven past the front gates to wait by the central pool. Around it are those poled carports for the at-least-five-year-old Toyotas, Hondas, and Fords. I’m supposed to meet him somewhere near here, and I’m looking at as many of the two-story buildings with digit names and strange mansard roofs as I can. I finally find him under a tree, using it for an umbrella. The plan was to go to a nearby place, and, zip-zip, we’re there, but they’re not. Closed. Now it’s raining. And humidity not only steams my glasses, it fogs my car’s windows from the outside. I have no choice but to roll them down to see out the side mirrors. All of this trouble I’ve caused! We’re in the road maze—auto repairs and parts, discount furniture, strip joints and liquor stores—what residents speed through as on a highway, me driving slow only in comparison. When I saw Jefes (not the possessive, the plural!), we both agreed it was it.

I don’t think either of us had been so hungry. We were relieved it was open and we were out of the car. Inside, it was like we’d dropped in on Mexico, and as its only customers, so many tables, anywhere, we felt like opulent guests. Where’s a more perfect North Austin setting—the grumble of a Texas double-wide road right over there—for the First Resident of Belken County and me, a simple citizen?

I had my other questions—about his visits, as a Chicano writer in America, to Spain and Germany (he does speak a little German); about the little visibility of his war years, Korea, paralleling his visibility as a writer (he’s proud of his war poetry); about his early influences (young, he read all the time, everybody in his home did, and in the Valley it was in Spanish and English, and his best friends became writers Tomás Rivera and Américo Paredes)—but the one that mattered most to me was about home: he not only goes back to the Valley often, that very week he’d be giving the commencement address at Mercedes High School, where he himself graduated so many years ago. He’s lived in Austin since 1981, when he took a position at UT, and one of his daughters lives here. Driving himself a few hours to give back, or taking a bus across town to the job he is devoted to, being near those who love him, whom he loves . . . what else?

But that can’t be a good enough ending! Must be the restaurant was too México Mexican, or instead of a ranch on the Río Bravo, I was driving him back to an apartment complex to grade papers? But wait. It’d become a beautiful day when we opened the glass door. The sun was out, the gray sky blued. It wasn’t even hot. But no Aztec dancers with shell anklets and headdresses of feathers de quetzales. No mariachis in trajes de charro, the trumpets aimed high, the bajo sextos loud and low, the deep clucks of a bass, and a few gritos of pride.That would have been nice in Hollywood or even in New York—would’ve been nice in Austin or in the Rio Grande Valley—but this: don Rolando Hinojosa, calm and steady as always, past all the battles and wars, was still here, right here as he has been for so many, many years, and he is home, as he will be for so many years to come.

- More About:

- Books