The neighbors call it the “warehouse,” and even on its modest street lined with small frame houses and light-industry buildings, it is unprepossessing—on the outside. The surprise is that inside the two-story corrugated metal building is the home and art collection of Houston gallery owner Fredericka Hunter.

Situated on a corner lot in an area east of Houston’s Memorial Park, the shed-roofed duplex is almost hidden by trees and desert plants. The neighborhood is a democratic mixture of blacks, Chicanos, and whites with a retinue of children and pets, plus a Popsicle man who comes around every afternoon.

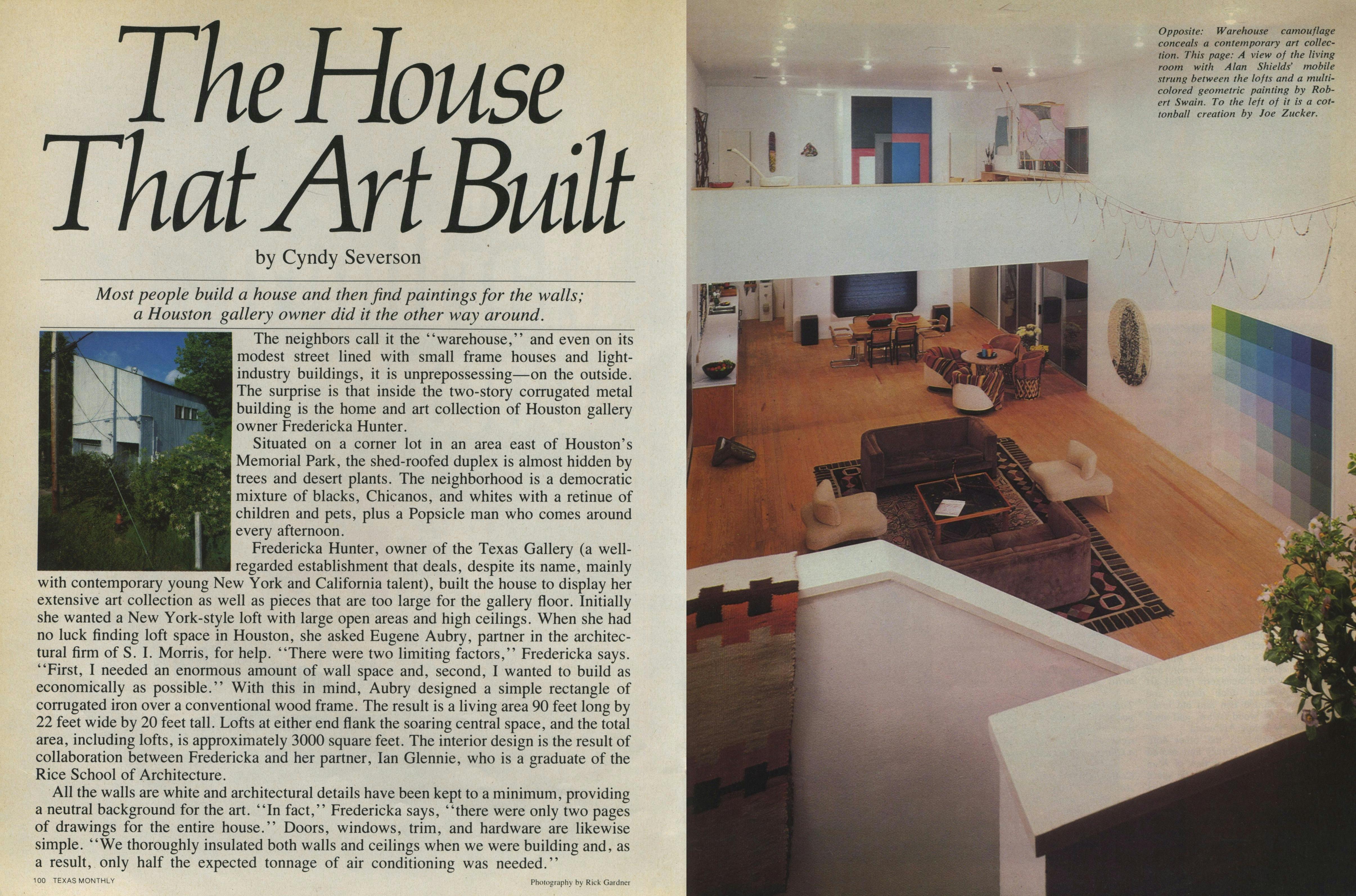

Fredericka Hunter, owner of the Texas Gallery (a well-regarded establishment that deals, despite its name, mainly with contemporary young New York and California talent), built the house to display her extensive art collection as well as pieces that are too large for the gallery floor. Initially she wanted a New York-style loft with large open areas and high ceilings. When she had no luck finding loft space in Houston, she asked Eugene Aubry, partner in the architectural firm of S. I. Morris, for help. “There were two limiting factors,” Fredericka says. “First, I needed an enormous amount of wall space and, second, I wanted to build as economically as possible.” With this in mind, Aubry designed a simple rectangle of corrugated iron over a conventional wood frame. The result is a living area 90 feet long by 22 feet wide by 20 feet tall. Lofts at either end flank the soaring central space, and the total area, including lofts, is approximately 3000 square feet. The interior design is the result of collaboration between Fredericka and her partner, Ian Glennie, who is a graduate of the Rice School of Architecture.

All the walls are white and architectural details have been kept to a minimum, providing a neutral background for the art. “In fact,” Fredericka says, “there were only two pages of drawings for the entire house.” Doors, windows, trim, and hardware are likewise simple. “We thoroughly insulated both walls and ceilings when we were building and, as a result, only half the expected tonnage of air conditioning was needed.”

Including appliances, burglar alarms, and smoke detectors, the total cost came to a frugal $22 per square foot.

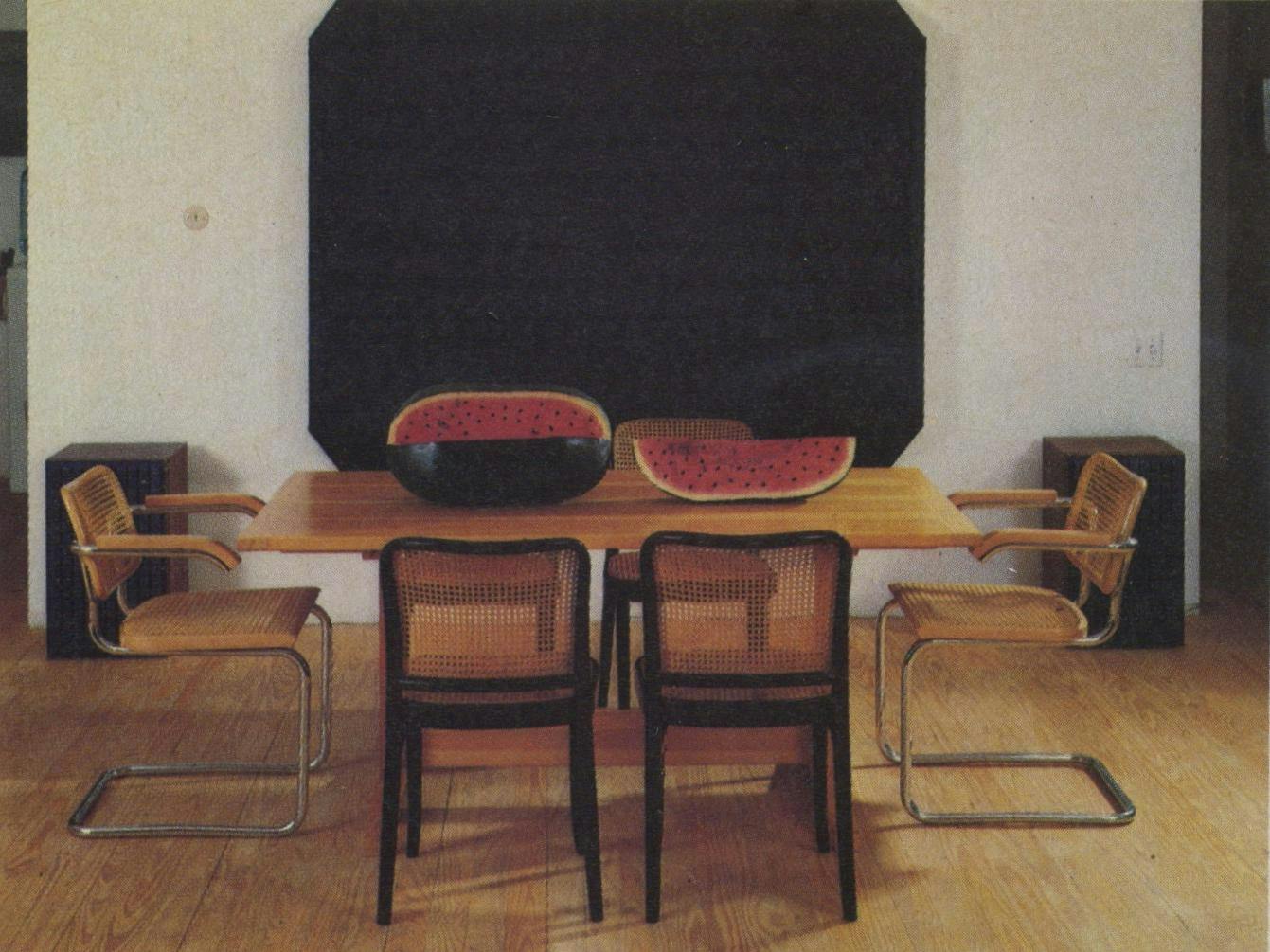

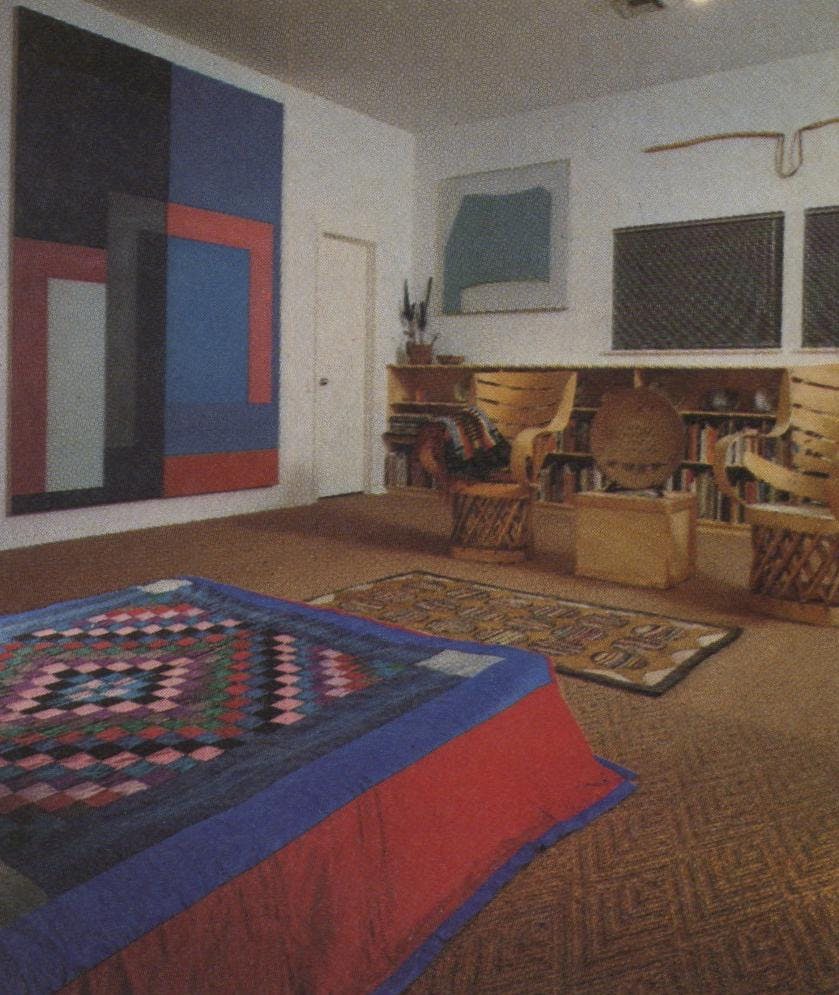

The house is sparsely furnished and looks as if all but the bare necessities have been pared away, but artwork gives tremendous life to the space. A thirty-foot painting in three parts by David Novros hangs on one wall of the living room, while the opposite wall holds four pieces ranging from large painted canvases to stick constructions. Various metal sculptures are placed about the house, as well as an extraordinary collection of rugs, tapestries, and quilts.

“The kitchen isn’t elaborate,” says Fredericka. “It’s not much more than one long counter.” But the cabinets hold a collection of Mexican Fiestaware in every hue, and on one side, sliding glass doors open onto an enclosed deck for breakfast out-of-doors.

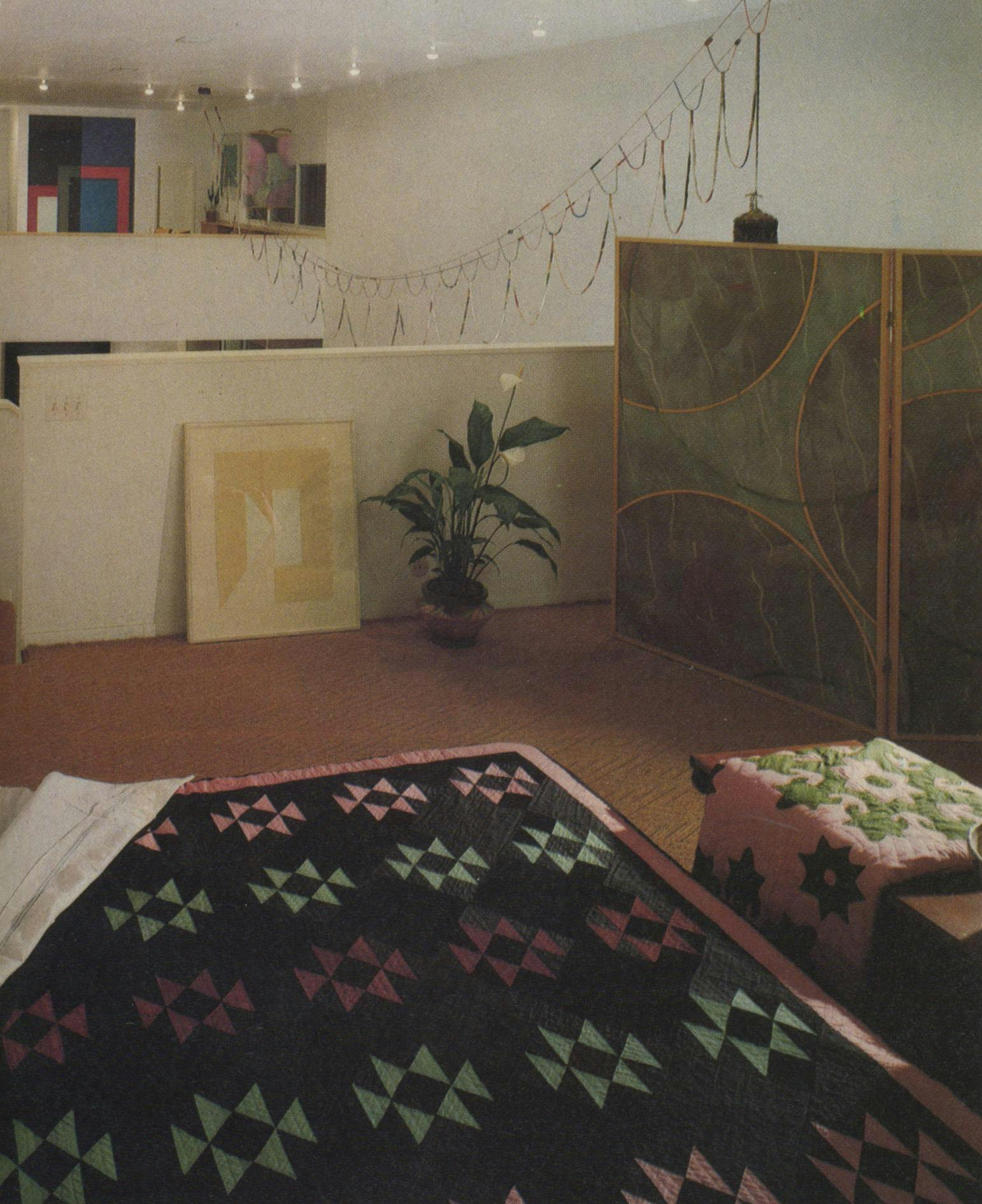

From a bedroom loft, which looks as if it is suspended in space, there is a striking view of the living area below. The stairs and landing are covered with sisal in a repeated chevron pattern and the bed with a patchwork quilt from Federicka’s collection. A Billy Al Bengston screen fills one corner, and beside the bed is a menagerie of folk-art animals: wooden duck decoys and sandpipers, painted fish and old lures, and a fantastic wood, straw, and stick porcupine by Felipe Archuleta.

Looking across to the other loft, which doubles as a library and second bedroom, one has a good view of Alan Shields’ mobile, which spans the space between the two balconies. Three tiers of shelves line two walls of the loft, containing a fine collection of prehistoric American Indian pottery as well as a variety of books. A colorful canvas by David Novros and an early-American rag rug combine to make this one of the most inviting rooms in the house.

Fredericka’s home is extremely flexible. Besides providing a background for her art collection, the large central space flanked by balconies provides a perfect setting for the small impromptu music, dance, and dramatic productions that Fredericka frequently holds when friends from other areas of the art world come to visit. The space becomes a stage just by shoving aside the few pieces of furniture. “It’s a wonderful space,” she says, “roomy and open for large gatherings.” When everything is put back in its place, the house provides a cool quiet atmosphere in which to rest and contemplate.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Art

- Architecture

- Houston