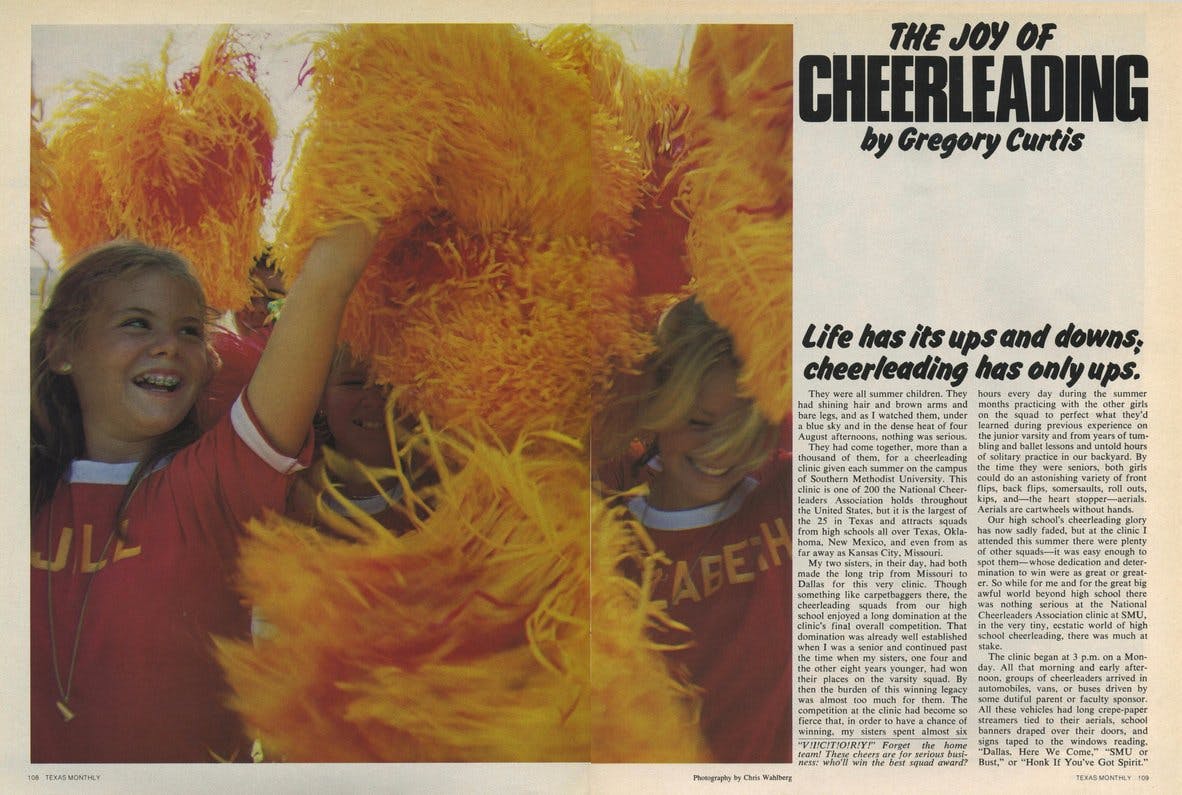

They were all summer children. They had shining hair and brown arms and bare legs, and as I watched them, under a blue sky in the dense heat of four August afternoons, nothing was serious.

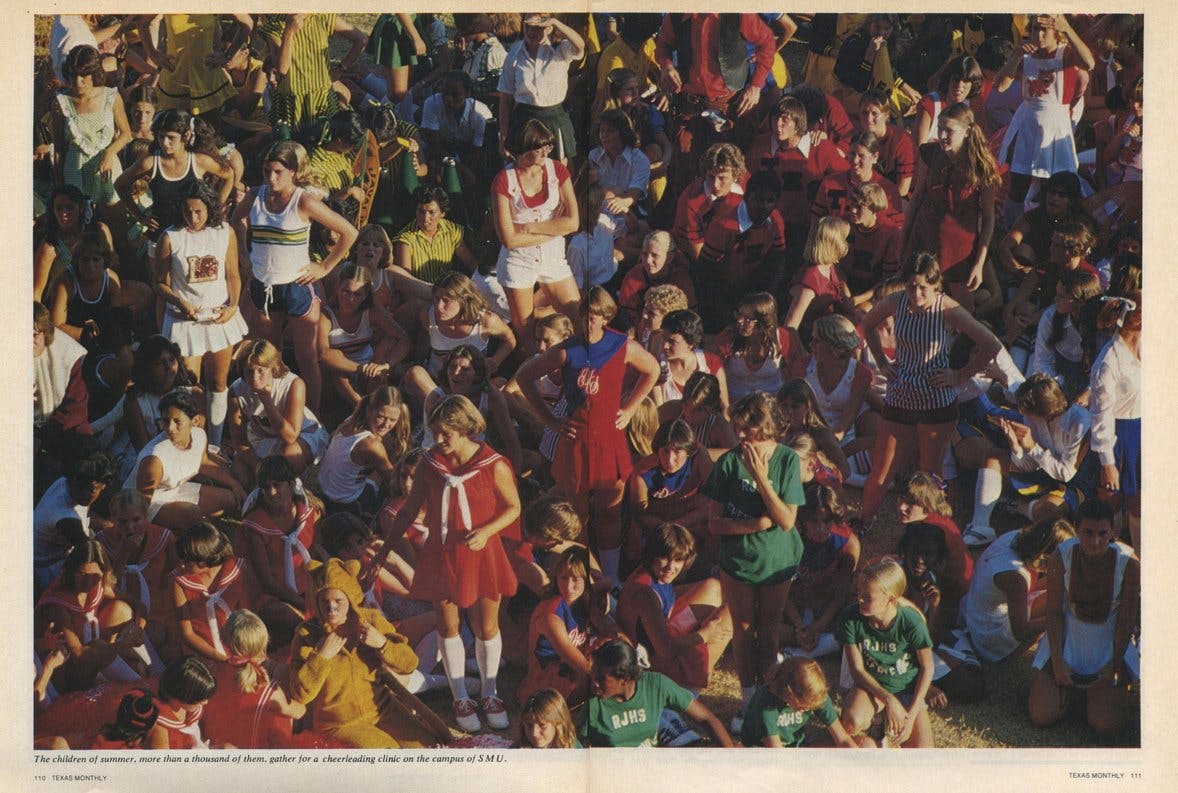

They had come together, more than a thousand of them, for a cheerleading clinic given each summer on the campus of Southern Methodist University. This clinic is one of 200 the National Cheerleaders Association holds throughout the United States, but it is the largest of the 25 in Texas and attracts squads from high schools all over Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and even from as far away as Kansas City, Missouri.

My two sisters, in their day, had both made the long trip from Missouri to Dallas for this very clinic. Though something like carpetbaggers there, the cheerleading squads from our high school enjoyed a long domination at the clinic’s final overall competition. That domination was already well established when I was a senior and continued past the time when my sisters, one four and the other eight years younger, had won their places on the varsity squad. By then the burden of this winning legacy was almost too much for them. The competition at the clinic had become so fierce that, in order to have a chance of winning, my sisters spent almost six hours every day during the summer months practicing with the other girls on the squad to perfect what they’d learned during previous experience on the junior varsity and from years of tumbling and ballet lessons and untold hours of solitary practice in our backyard. By the time they were seniors, both girls could do an astonishing variety of front flips, back flips, somersaults, roll outs, kips, and—the heart stopper—aerials. Aerials are cartwheels without hands.

Our high school’s cheerleading glory has now sadly faded, but at the clinic I attended this summer there were plenty of other squads—it was easy enough to spot them—whose dedication and determination to win were as great or greater. So while for me and for the great big awful world beyond high school there was nothing serious at the National Cheerleaders Association clinic at SMU, in the very tiny, ecstatic world of high school cheerleading, there was much at stake.

The clinic began at 3 p.m. on a Monday. All that morning and early afternoon, groups of cheerleaders arrived in automobiles, vans, or buses driven by some dutiful parent or faculty sponsor. All these vehicles had long crepe-paper streamers tied to their aerials, school banners draped over their doors, and signs taped to the windows reading, “Dallas, Here We Come,” “SMU or Bust,” “Honk If You’ve Got Spirit.”

By 3 o’clock all but a few squads had arrived, found their rooms in SMU’s rather prosaic red-brick dormitories–the girls in buildings far from the boys—dressed in their uniforms, and made their way to McFarlin Auditorium. This building, which has a plain but imposing facade, is nothing more on the inside than a high school auditorium. It has the same wooden seats with the same wooden backs, the same stage at the front, and the same colorless, almost dingy stucco walls. By 3 o’clock it was filled with a collection of American youth ideal in the extreme. They were, like the neon signs in Las Vegas, so bright and dazzling that watching them was almost painful. Bright eyes! Smooth skins! Lean bodies! Gleaming teeth! They stood before the auditorium seats dancing back and forth and chanting, “V! I! C! T! O! R! Y!”

This victory was for no one in particular. There were no teams, no games, no crowds except themselves. It was summer. Nothing was serious. They were simply cheering.

Suddenly the red velvet curtain across the stage parted to reveal a rather plain woman in a styleless blue dress. She insisted that everyone sit down so she could explain the rules for the week.

“There will be no dates,” she said.

The cheerleaders booed loudly.

“There will be no drinking.”

This received some immediate boos that were quickly drowned in nearly universal cheers.

“The dorms will be locked at ten o’clock.”

I expected this to elicit, not a boo exactly, but a loud sigh of abandoned hope. Instead they cheered.

The woman in the blue dress now introduced Lawrence R. Herkimer, known to everyone as Herkie, the head of the National Cheerleaders Association. A short, rotund, balding man of about fifty, he is, beyond debate, the greatest cheerleader of all time. In the late forties he was he head cheerleader at SMU, where he invented that universal cheerleading trademark, the “Herkie Jump,” in which the cheerleader leaps up with one leg straight and the other one bent behind him. He has made a more than respectable fortune running these clinics and selling cheerleading uniforms, pom-poms, megaphones, and the like. And he or his staff has written virtually every cheer, except for the most ancient and traditional ones, that American sports fans have heard in the last 25 years. His appearance was greeted with the longest and most resounding cheer so far.

“Some of you here may be cheering for the first time,” he said. “I know how it is. The first time you’re up in front of people you’re shy and quiet. Then the next time you just go ahead and cheer. And then the third time you come out and say, ‘Okay, you lucky devils, here I am!’ “

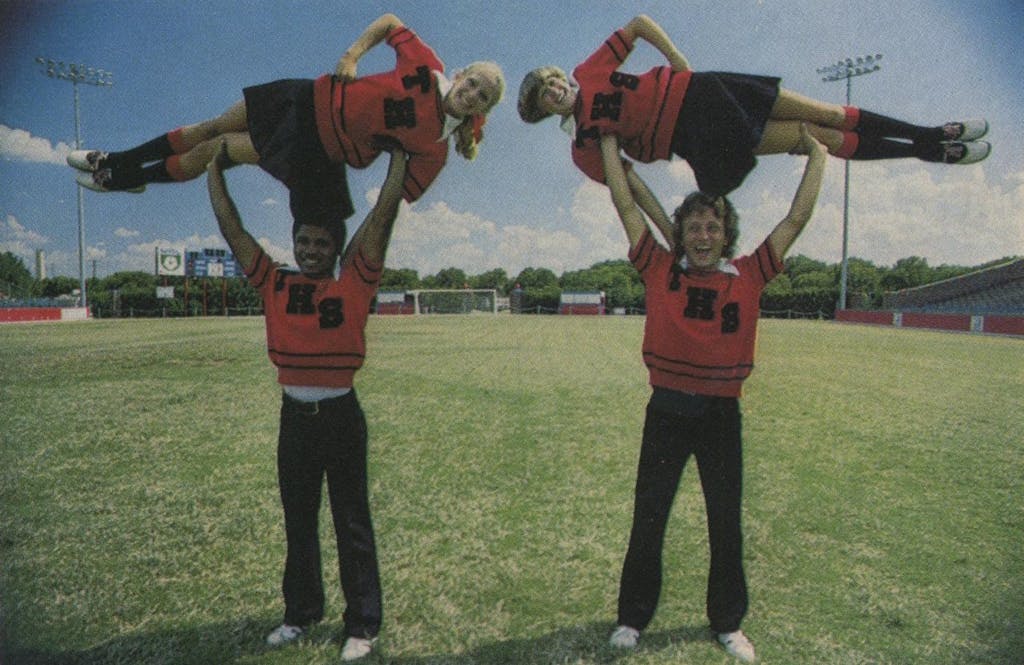

Herkie then introduced the teaching staff. It was divided into two groups, the six boys and nineteen girls who would instruct the high school squads and the seven boys and four girls assigned to the much smaller college clinic. They performed some cheers and explained a few of the things they would be teaching that week. “We’re going to show you how to build effective pyramids that are real crowd-control pyramids,” was one promise. Then they dismissed everyone for dinner and the first classes, which would begin at 7 p.m.

All the staff were either in or just out of college and the many were currently cheerleaders at schools like Texas and Texas Tech. But the eleven instructors who led the college clinic were far more accomplished than the rest. Some could, for instance, jump off small trampolines, flip in the air, and land in a hand-stand on another’s shoulders. Still, after watching the college squads practice that evening, I decided to ignore them in favor of the high school clinic. College cheerleaders strike me as being just a bit too old for what they’re doing. Clearly, college football is a business, often a grim one. Most college cheerleaders are aware of the commercialism of what they’re cheering and in many cases that commercialism may even be the cheerleading’s exact appeal. But all that still leaves them slightly jaded. One cheerleader, clearly more jaded than most, walked from he college clinic that night enthusiastically chanting, “Manic! Depressive! Manic! Depressive! Catatonic schizo, Go! Fight! Go!”

Of course no high school cheerleader would so blaspheme school spirit. That would be a transgression as serious as demanding to know why evil so often triumphs over good or whether cheerleading has any purpose in an imperfect world. And indeed, these questions seemed not only unimportant but also inconceivable the moment I finished my long walk across the campus and came upon the high school squads at that evening’s classes.

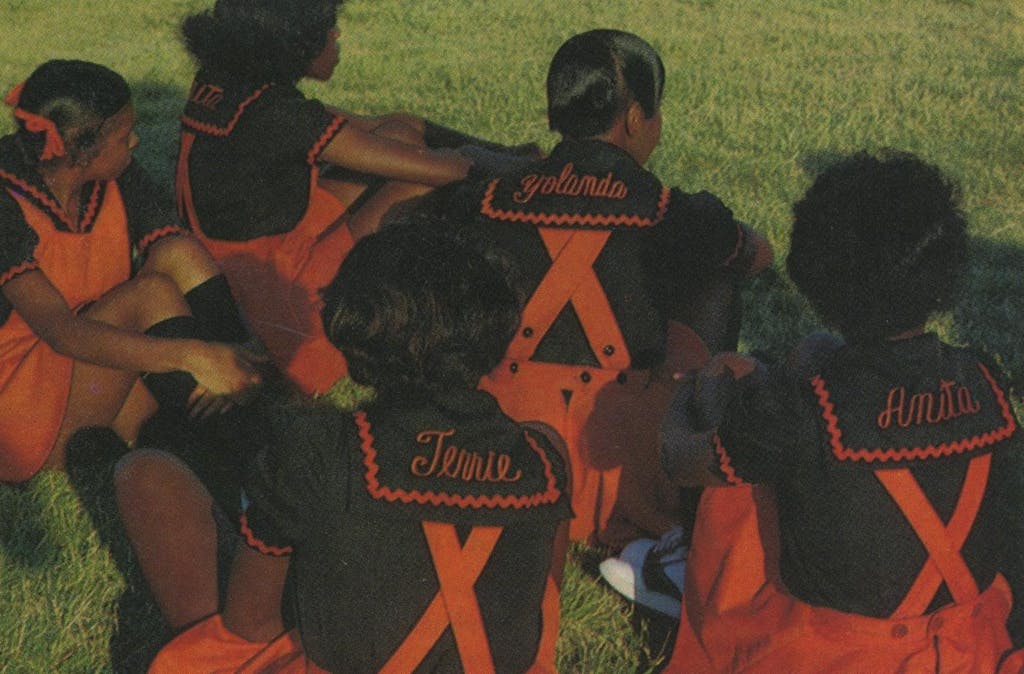

Between the meeting at McFarlin and now, everyone had not only eaten but also bathed, put on fresh uniforms, and carefully combed their hair. Many of the girls, who despite the surprising number of boys still made up the great majority, had put on a modest amount of makeup and a somewhat greater amount of perfume. One brand in particular seemed to be he cheerleaders’ favorite for evening this year. Slightly heavy and dizzyingly fresh, I smelled it everywhere as I walked around watching this group and that practice their cheers, flips, and crowd-control pyramids. Everyone was spread out in small groups across a large, gently sloping field at the south end of the campus. Their cheers were good-natured and energetic as individual squads took turns performing for their group. The afternoon heat had relented, a row of elms along one side of the field cast long shadows as the evening began to fade, and my only concern was trying to decide on the proper tone for approaching an adolescent girl to inquire, “Can you tell me, please, what is that scent you’re wearing?”

The first day ended well after dark with the cheerleaders gathered in a half-circle around the instructors. Everyone joined hands and, swaying back and forth, sang, “Friends we are, and friends we’ll always be/ Together we will cheer so faithfully…” And then the meeting was over and the summer children walked back across the campus to be locked in their dorms until morning.

Morning classes began at 7:30. Here the instructors trotted out new cheers and taught a certain amount of acrobatics and stunts. This was the least interesting part of the day for me since I could see no particular reason for my learning that “Score Six” begins with a pivot to the right and the arms held straight in front or that “Up and Down” ends with a lunge forward on the right foot and the arms extended in an upside down V. But the cheerleaders found the mornings more exciting. “You want to know what I learned in camp today?” one boy cheerleader said when I had stopped to talk with him shortly before noon. “I’ll show you what I learned in camp.” And he stepped into the cupped hands of another boy on his squad who thrust him high in the air where he turned a back flip before coming down. He turned back to me in triumph, his chest swelled, and he said majestically, “That’s what I learned in camp.”

After the morning’s emphasis on the practical, the afternoon class concentrated more on the philosophical. Meeting in Moody Coliseum, SMU’s basketball pavilion, everyone first went through all the cheers they’d learned in camp. Then they had to learn some new ones before settling down to an hour or so of lecture. Tuesday’s was given by Dirk Johnston, a former SMU cheerleader who was the chief instructor for this camp and plans to begin working for Herkie full-time this fall. Johnston wants to make cheerleading his career. His main topic was, “What Is a Cheerleader?” The talk was not without a certain logic. Cheerleader: “…someone chosen from the crowd to cheer, a cheerleader; but also someone who leads, a cheerleader…” Johnston also ranged among such topics as how to make an entrance at a pep rally (anyone who can tumble or do acrobatics goes first and the rest follow), voice projection (use your diaphragm), and how to get that group of guys who sit in the stands and never cheer to start cheering (use eye contact). The students listened politely if not so attentively as they might have. They had come to camp to cheer and having to do anything else—not mater how closely related—left them restless.

In the evening everyone met on the same large field they’d used on Monday. At one end of the field, near the entrance to a dormitory, was a slight rise from which the instructors called everyone together at 7 p.m. For fifteen or twenty minutes, with the squads spread out in a wide semicircle around them, the staff led the cheers everyone was learning at the camp.

There were three or so of these new cheers every day, the same ones that are taught in ever clinic across the country. Herkie and members of the clinic staffs write the cheers and work out the accompanying routines at a large meeting at the University of Oklahoma in April. They are then tested at cheerleading clinics in Southern California, the part of the country where the hierarchy of the National Cheerleaders Association thinks kids are the most difficult to impress and the most attuned to the latest popular trends—in other words, the coolest. “If the California kids like a cheer,” Dirk Johnston told me, “we know kids everywhere else are just going to go berserk about it.” This fall high school football fans can count on hearing “Super Great,” “Ease on Down that Line,” “Up and Down,” “Party,” and “The Gong Cheer,” as well as such less inspired new offerings as “Score Six Points” and “W-I-N.”

After the group cheering, everyone was divided into 25 groups of four or five squads each, which then spread across the field like vivid, tropical islands in a sea of grass, under the supervision of an individual instructor. These little meetings were the most important things that happened all day: as each squad took turns performing two cheers, the other squads and the instructor evaluated their performance. The cheerleaders offered their criticisms verbally to the expectant, determinedly smiling, and slightly winded performers. “I thought you didn’t end together,” someone might say. “Oh, okay,” would be the response. “Thank you, very much.”

But the instructors had small, blue evaluation forms. They appraised the timing and rhythm of the cheers and noted the amount of eye contact and voice projection. They graded how well a group’s stunts, tumbling, pyramids, and jumps were incorporated into the cheer. Basically, these must be done smoothly and without breaking rhythm They watched for whether thumbs were held in or out; out being bad. They noted bent arms; arms should be straight. They noted arm angles, which should never be anything but 45, 90, or 180 degrees. And they made a somewhat subjective judgment of a squad’s overall spirit and enthusiasm. When each squad had performed, the instructors retreated back to the top of the little rise where, alone, they studied their evaluation sheets to decide how to commend the squads they’d seen. The prize ribbons were all labeled, as summer ribbons should be, in superlatives: superior, excellent, and outstanding. Every squad received a ribbon of some sort. Each announcement caused tremendous hugging, jumping, squealing, and even crying from the squad receiving the ribbon and polite, though not perfunctory, cheers from the other squads.

The awarding of the ribbons completed the business of the small groups, but not of the evening meeting. Everyone now returned o the small rise in front of the dormitory where, once again, the instructors led the multitude in cheer after cheer. Then came the awarding of spirit sticks, the climax of the day. There were about fifty of these foot-long dowels painted red, white and blue. While getting one was important enough to cause an outbreak of hugging, jumping, squealing, and crying that made the response to winning a ribbon seem like a funeral dirge, it was still no quite so important as not getting one. If a squad had any ambitions toward being in the final competition, those spirit sticks, since they represented the approval of the staff for that day’s work, became crucial objects. The year that the older of my sisters came to SMU, her squad didn’t win a stick the first three nights. After that third disappointment they trudged back to the dorms convinced they had no chance to be selected for the final competition. They crawled into their beds thinking that they would be the ones to break the unbroken string of victories, the ones from our school who, when tried, had failed. Miraculously, they were selected for the final competition and, fortunately, they won. But that is the kind of despair these spirit sticks can cause.

It is always dark when spirit sticks are awarded, and the staff members do what they can to make this event a tremendous production. Standing in a line at the top of the rise, backlit by the dorm lights, they jump and flip; the boys toss the girls in the air, catch them, twirl them around. The staff members clap, cheer, and dance in a show of almost suffocating enthusiasm after giving out each one of the approximately fifty sticks. The high school squads are supposed to equal this enthusiasm. It is very bad form for any group, no mater how disappointed they may be, to show anything but pure and absolute spirit. They shout, “We are proud of you! Hey! Hey! Hey! We are proud of you!” or ”Super great! Super great! Super great!” after each winning school’s name is called. With the awarding of the last stick, the day was over.

Herkie, of course, had created this intensive regime. There had been cheerleaders and cheerleading schools before him, but they seem very primitive compared to what Herkie has labored all his life to bring forth. Ivy league schools created and still use the oldest known student yells in the United States—Princeton’s dates as far back as the Civil War. But the first cheerleader in the modern style was Johnny Campbell, who was elected in 1898 from the student body of the University of Minnesota. Cheers in those days were very simple, the most famous being “The Rocket,” which goes “Sissssssssssssss…Boom!…Ahhhhhhhhhhh.” The Siss is the fuse, the Boom the explosion, and the Ah the response of the crowd. In time this was amended to “Siss, Boom, Bah,” which someone, in a moment of inspiration, realized rhymed with “Rah, Rah, Rah,” and from this tiny acorn…

I interviewed the greatest cheerleader in history on Wednesday afternoon. Herkie spends his summer in almost constant travel from one of his far-flung clinics to the next, so I was lucky to catch him at all. But we met halfway through boogie class, which was an unfortunate time.

Nothing has changed cheerleading so much in the last ten years as the incorporation of dance steps, up-tempo rhythms, and phrases from popular songs like “get down,” “do that stuff,” “taking care of business,” and “boogie.” No longer may a cheerleader jump twice in the air and shout, “Hold that line!” No longer may a cheerleading squad base all its routines on stiff, formal steps. The modern cheerleader must also know how to dance. This all started in California. Anyone who has seen the USC or UCLA “songirls” do a routine will understand why certain elements of their style have spread as far as they have. Consequently one afternoon at the clinic is devoted to teaching the cheerleaders certain rudimentary steps, adapted for cheerleading, from the hustle of other disco dances.

Herkie led me down a hallway in Moody Coliseum, which led to the SMU athletic offices, where we hoped, with the cheerleaders’ yells from the basketball floor resounding throughout the building, we could find a quiet place to talk. He is well known in these offices since he has remained a loyal supporter of his alma mater and has donated both money and equipment to the school. After graduating from North Dallas High School, Herkie was cheerleader at SMU in 1947 and 1948, years when SMU, with Kyle Rote and Doak Walker in the backfield, had something to cheer about. During his last year of college, Herkie conducted his first cheerleading clinic. It actually wasn’t his idea but that of a professor at Sam Houston State who enlisted an English professor to teach the cheerleaders diction, a physical education instructor to teach them basic gymnastics, and Herkie to teach cheerleading itself. The clinic, virtually the only one of its kind at the time, attracted a modest number of cheerleaders, but Herkie returned to Dallas convinced that the idea of a cheerleading clinic needed only to be refined. He convinced the professor to let him run the clinic the following summer, where he instituted a number of changes; most important, Herkie replaced the professors on the staff with cheerleaders.

That clinic was a success and Herkie began to set up other ones. He found colleges quite willing to help. For one thing the clinics filled their dorm rooms and cafeterias during the summer when they were normally empty and for another the clinics helped them recruit new students. Cheerleaders then and now tend to be the sort of bright and popular students that most colleges hope to attract. Letting a group of them live on the campus for a week was one way to attract them.

In 1949 Herkie had returned to SMU as a physical education instructor, but by then his clinics had grown to such numbers that by 1951 he had given up teaching and devoted himself to cheerleading. Now, in addition to his summer clinics, he holds numerous one-day or weekend clinics during the rest of the year, and conducts seven gymnastics clinics. He also sells cheerleading supplies and paraphernalia. All this has made him a very wealthy man. In Dallas those who have never been cheerleaders probably know him best for his service between 1973 and 1975 on the Dallas School Board, where he was an arch conservative.

We found an empty office and sat down in the nearest available chairs, which were across the room from one another. “We don’t teach cheers,” he said, “with words like ‘smash ’em, bash ’em’ or words in bad taste. We try to show the squads the really sharp things they can do. They ought to be proud of what they do. You see, cheerleaders have to work as a group. They have to get along together all fall under intense pressure and responsibility. So that’s why we don’t teach just skills but the philosophy of cheerleading, too.”

Herkie has a thick, watery voice and likes to punctuate his sentences with amused little snorts. For someone so successful, he occasionally has an almost bemused air, but more often he projects the radiant good cheer of a lifelong camp counselor. “I used to help with the Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders back when they really were cheerleaders. Now at their tryouts the girls just get up and shake around a little bit and they choose the ones that shake the best, I guess. Every fall I get calls where someone starts screaming at me, ‘I think it’s just terrible what you’ve done with those Cowboy cheerleaders.’ ‘Wait a minute,’ I say. ‘I don’t have anything to do with it.’ But that’s different. That’s professional, they’re really just putting on a show. What we’re teaching here at these clinics is all on a pretty high plane.”

When Herkie had to leave I walked back to the arena. The noise of boogie class had been replaced by the lone voice of Dirk Johnston speaking on what makes a good cheerleader. “If you try to be the best cheerleader you can be,” he said, “then you are doing what you can to make the best cheerleader squad. And if everyone on the squad does the best they can, then you will all be doing the most you can for your school. And if everyone in the school…”

The National Cheerleaders Association has 325 instructors on its staff. Two years ago, Herkie told me, he chose the best looking among the applicants and found that, to his way of thinking, he had a staff of prima donnas. “Since then,” he went on, “I’ve tried to choose my staff to give something for everybody. There’s the campus beauty queen, there’s the good old girl that’s homely as a fence post but everybody likes her. There’s the good tumblers, the great jumpers. Something for everybody.”

Actually the staff seemed more homogeneous to me. They were all likeable, right thinking, moderately attractive college kids, and the most remarkable thing about them was that their enthusiasm never faltered from the first moment of the clinic to the last. I asked one of the staff if she ever woke up in the morning and just didn’t feel like cheering. “No,” she said, “not really.” They cheered so long and so hard that all their voices were in need of a rest.

This was most noticeable among the girls, who all spoke with a deep, dry croak that was exactly like a whiskey voice. Contrary to what it might seem, this voice, in the context of all their freshness and zeal, added a worldly note that was rather appealing.

Since members of the staff live in close proximity during the clinics, travel together from one clinic to the next, and try to have some fun when they can, I had supposed that inevitably they would share in moments of extreme fun. But there are fewer of these than one might think. “Staff romances don’t work,” one girl told me. “You’re together for a week. Then you might not see each other again all summer. It’s too hard on everybody.” Also, at the SMU clinic at least half the staff were strongly religious. They read their Bibles during spare moments in their rooms. Several times I saw instructors praying quietly by themselves just before going on stage to perform. Generally, they regard their work as a good summer job. They make about $100 a week to start, get to ravel, meet lots of people, and the kids at the camp regard the staff with the same reverence a high school athlete might have for an all-American.

The kids, of course, thought they were in heaven during the whole week. Their single, universal opinion was that the clinic was “great,” and no matter how many cheerleaders asked, I never failed to get the same reply. My one hope for a different opinion was a boy I’d seen on the first night. He had a sullen, bored expression and sulked through the motions of his cheers. If the instructor insisted that everyone hold his arms straight, this boy made sure his were bent. But by Thursday, when I finally had a chance to talk to him, there’d been an immense transformation. He was cheering with total enthusiasm. “This place,” he said to me, “is just great.”

The clinic had no real ending. Whatever is not serious doesn’t end. Instead it drifts away or peters out or slowly evaporates because anything definite and important enough to be an ending would also be serious. The final competition was held on Friday morning in Moody Coliseum. The squads from R.L. Turner of Carrollton and from Richardson were declared co-winners. My own favorite had been the squad from San Antonio Central Catholic, whose team name was not the tigers, warriors, rebels, bears, or pirates, but the buttons. Then there were a few minor announcements before the staff shouted, “That’s it. Bye, everybody.” No last cheer, no holding hands and singing, no moment of silence. Instead the cheerleaders, now with no one to lead them, milled around aimlessly for a moment and then began to leave the coliseum to pack for the trip home. One girl game running up to me. “Be sure to mention my name in your story,” she said.

“All right, what’s your name?”

And her reply seems as good an epitaph as any for the 1977 SMU cheerleading clinic: “Cindy Arnold, Spring Wood High School, Houston, Texas.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Longreads

- High School

- Football

- Dallas