Excerpted from The Texans, by James Conaway, to be published this spring by Alfred A. Knopf.

“My only regret is that Dean isn’t here now, so I could tell him what a good job I did killing him.”

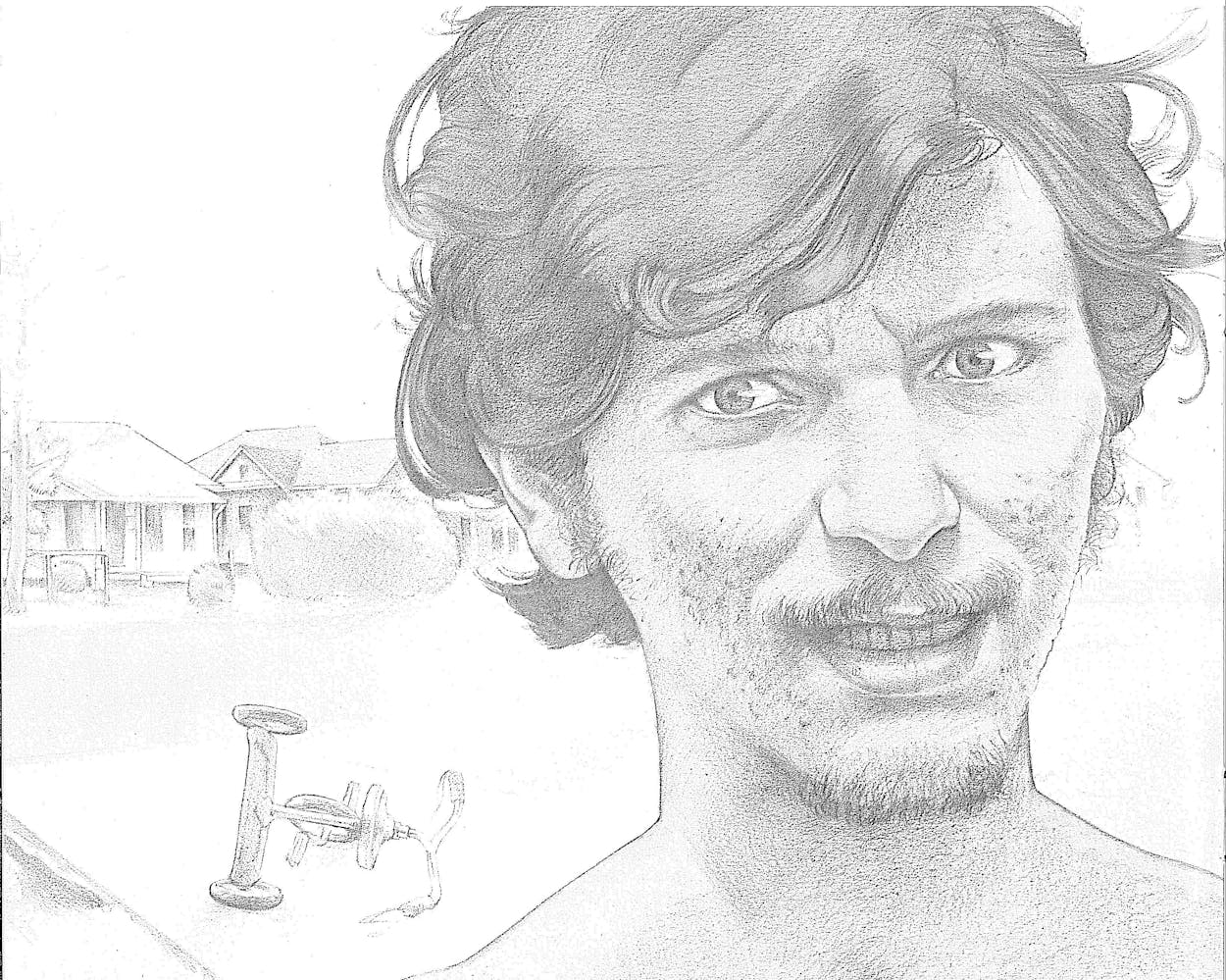

He sits cross-legged on a folding chair in the hospital ward of the Harris County jailhouse, laughing and brandishing a Marlboro. White fatigues hang open at the neck, revealing a sunken chest and the colorless flesh of the restricted prisoner. Rubber thong sandals dangle from grubby toes; gone are the wispy beard and shoulder-length hair of those blurred news photos, replaced by dark, oily curls pressed against his head. Bluish acne scars cover his cheeks and the back of his neck; beneath curving brows lies the intimation of his reputed IQ of 126. The eyes dominate a face most notable for its nastiness, speckled green and too large, conveying an extraordinary distance that continues to impress long after the gaze wanders, the ready smile fades.

“It was,” says Elmer Wayne Henley, snapping his fingers, “such cool. Dean had been training me to react, to react fast and to react, greatly. That’s exactly what I did. There wasn’t anything that could have made me more uptight than to have been drunk and stoned and hungover and having withdrawals, and then I just blew his life away. He’d of been proud of the way I did it, if he wasn’t proud before he died.”

Seated with us in the dentist’s office—it affords the only privacy in the ward, where Henley is considered safest from the two dozen people who have vowed to kill him—is one of his defense attorneys, a retired army officer in owlish spectacles. He is obviously pleased with his client’s performance. Henley will shortly be sentenced to 594 years by a San Antonio court, but that is a formality. The lawyer and his young partners want to sell Henley’s life story to recover their fees, and they see this exclusive interview as a kind of literary screen test.

“Now, Wayne, tell him how you did it.”

There is a coziness here that goes beyond sweating together. Another project entirely brings me to Houston, and yet it seems quite proper while here to be dealing with Henley, a commodity as valuable as a state bank charter or a fast-food franchise. Although I have conducted hundreds of interviews, I am uneasy in the presence of this high-school dropout from Houston Heights. That some things are best left under rocks is not a sentiment appropriate for journalists; yet is there any point in plumbing the random, insane horror known as the “Houston Murders”? Many children buggered, tortured, strangled, and discarded with fiendish intent—a process that took years. Was Texas—was the country—honeycombed with the decomposing victims of some hidden force so demonic that it eluded ordinary perception and even memory lay buried?

“I had Dean in a corner, see, and he told me, ‘You won’t kill me.’ I shot him—coolly—until I ran out of bullets. I shot him once in the forehead; my hand went down, and I shot him twice in the shoulder. I stepped aside, he ran through the door, and I shot him once in the back of the shoulder, and twice in the small of the back. To make sure he stayed shot.”

“We’ve got this problem of culpability,” the lawyer had said earlier, when the two of us were seated outside in his dusty Cadillac, the windowsills too hot to touch. “From what Wayne says, there may be more bodies out there.” He gestured vaguely in the direction of the Gulf of Mexico, where in August 1973, police discovered the remains of seventeen teen-age boys beneath the dirt floor of a boat shed, wrapped in plastic shrouds and laced with lime, and subsequently dug up ten more along a lonely stretch of beach.

“Maybe there’s not just twenty-seven murders. Maybe there’s forty, maybe more. If I were you, I wouldn’t want to know.”

Houston Heights is a seedy, lower-middle-class enclave with horizons limited to once-fashionable homes divided into low-rent apartments, and guarded by pickups on concrete blocks. White adults drink Pearl beer in Billie’s Gold Brick, and more than a few teenagers risk mind-dissolving highs by “bagging”—spraying acrylic paint into paper sacks, and breathing the fumes. Here Henley and a schoolmate, David Brooks, failed the ninth grade together, “skipping, smoking a little weed, shooting pool.”

Brooks introduced Henley to Corll, a heavyset employee of the Houston Lighting & Power Company, who was twice their ages. Corll’s apartment provided a place “to waste time.” Henley realized that the candy shop operated by Corll’s mother—where her son constructed a giant frog with red eyes that lit up when the telephone rang, for the amusement of children—was a store he had visited earlier.

“I admired Dean because he had a steady job. In the beginning he seemed quiet and in the background, and that made me curious. I wanted to find out what his deal was. The fact that he did work, wasn’t a wild drunk, got along with kids and people in general—that’s what started it.”

Much of that first year was spent driving aimlessly about the Heights in Corll’s car, drinking beer and smoking marijuana and planning petty theft. Henley suspected that Corll was homosexual—“I just figured David was hustling himself a queer”—a fact that had remarkably little influence upon his opinion of Corll.

“Dean’s front was wholesome and masculine. He had a big build, but he was flabby. He never really impressed me as masculine unless he was lifting something. He was a loner in his own right. He could be around people, but still you never knew what Dean Corll was doing. No matter how much you talked to him, you didn’t know him.”

So Corll not only provided an address—a curious sense of belonging to his fictitious “crime ring”—he was also an inspiration, an intimation that life held some mystery beyond the Heights. His homosexuality played second fiddle to this aura of experience and latent power, as viewed in the boys’ narrow perspective. Brooks became emotionally dependent upon Corll, and played a passive role in later, demented exaltation, for which he would be sentenced to only 99 years. But Henley wanted money. His other needs would prove too complicated for ordinary sexuality, hetero or otherwise, and would match those of his mentor, but with a deadlier lack of passion.

“Sex didn’t become a factor until later. There were rumors going around school about Dean, but he was never overt. Besides, I liked him personally. By the time he finally made an advance, I was an accomplice.”

Fellatio was just another antidote to boredom, no more disagreeable than bagging. Dean was a “personal” friend, as well as a source of income. When he instructed Henley and Brooks to bring him boys, instead of stolen television sets, to be sold to a fictitious white-slave market in Dallas for $200 apiece, they complied. Delivering up friends was easier, less risky, more prestigious.

Henley’s view of himself at that time is instructive.

“I was known as a playboy, a party person. I got along with everybody. And people knew that if you ran around with me, you ran around with broads.”

An ideal procurer.

“At first I didn’t sense that Dean might be a murderer, but later I did sense it. He brought out a little blade, you know—and it wasn’t a little knife, either. It was a great big knife. He was still talking about organized theft, and wanting to know in case was I cornered, was I willing to off the guy. Of course I said yes—ego would dictate that.

“I stayed around because there was no reason for me to leave. I didn’t have to do nothing but steal. Before kids started coming around, we got money from Dean for thieving, for setting up places to rob. I didn’t think there was anything to it, but at least I did get money for it. That’s what kept me around before he started talking about killing people. Later, he got down to the fact that we was going to be killing people.

“At first I wondered what it was like to kill someone. Later, I became fascinated with how much stamina people have. I mean, you see people getting strangled on television and it looks easy. It’s not. Sometimes it takes two people half an hour.”

Henley’s earliest memory is of near suffocation. Acute asthma attacks were overcome with the aid of his grandparents, who tended Henley while his mother was occupied with younger children and an unpredictable husband. Henley remembers sitting on his grandparents’ bed in the morning, while they drank coffee and read the Houston Post —his fondest recollection, set close to that of survival.

“They had a little dinner tray they put on the edge of the bed to hold the cups. I liked being there. I owe my life to them.”

He describes his grandfather—a hard-working baker who died when Henley was only seven—with a term that for him is close to adulation. “He loved his children and his grandchildren, he was sharp.”

Not so Henley’s father.

“We didn’t get along. Dad was always beating up on my little brothers. He overreacted, out of meanness. He beat up my mother, he beat up my mother and my grandmother once, at the same time. Maybe that’s what started it, the divorce and all I trapped him over the head with the vacuum cleaner, and called the police.”

Henley says his father also beat him and once fired a pistol at him. The son attempted to assume the role of surrogate provider, worked at odd jobs and gave some money to his mother, took a proprietary view of his old man.

“Dad just wasn’t straightening out. He was getting drunk too much, getting too rowdy. I thought divorce was a good idea, and I told him so. I hated to lose my father, but since then we’ve just had a little friction. He and I can get along for a little while, when he’s half sober and I’m half sober.”

Henley’s mother told police that Dean Corll was “like a father to Wayne.” Corll was himself the product of quarreling parents, who divorced when he was young, remarried, divorced again; his mother traveled around the South in a trailer, started a candy business with the help of a dutiful son. Corll was an average, submissive student who played the trombone in the Vidor school band, on the outskirts of Beaumont.

His mother married a salesman, divorced him, later married a merchant seaman and divorced again. Corll stayed with her through it all, obtaining a hardship discharge from the Army to return to the family candy business, this time in Houston. There he gave free candy to young boys, and entertained them in a back room outfitted with a pool table and the big green frog whose eyes lit up when the phone rang. His mother moved to Colorado, but this time Corll didn’t go with her.

If there’s a common theme among the boys it is rootlessness. David Brooks’ parents were also divorced, so were the parents of most of the victims. The Houston police claimed they were runaways, in an attempt to cover up what must be one of the grossest displays of inadequacy of any police department. If a child in opulent River Oaks had disappeared, the force would have mobilized, but those reported missing in the Heights were considered de facto trash, and expected to drift.

The truth is that some of the victims were traveling no further than the corner store (one on his bicycle), that for three years Houston authorities did nothing but add names to a list on a clipboard. No one seemed impressed by the fact that the unusually large number of “runaways” in the Heights involved teen-age boys who attended the same schools. No one had the energy to discover what was common knowledge among students: that any kid who wanted could turn on and pick up a few bucks by allowing a certain fat electrician to go down on him—and that some who had done so were no longer around.

Hunter and prey were products of divided families that owed more allegiance to the hardscrabble farms of the past than to the pavement of the present. Their parents seemed unwilling or incapable of providing direction. Murderers and murdered all drifted in a common miasma of thwarted desires, vague longings, sordid gratification—a quest of sorts. “Dean searched for a climax he never found,” says Henley. He was not the only searcher—just the most cunning and desperate, and quite mad.

Three years before his death, his mother had sent him an inspirational book entitled This Thing Called You. She inscribed it: “From your 54-year-old mother who has just begun to live. . . . Read this book and help me make up for the things I was too ignorant to teach you when I was in my twenties.” Four days before his death, Dean telephoned his mother in Colorado and told her he was in trouble, feared he was losing his mind, and might commit suicide. She sent him a box of candy.

Henley represents a larger problem because he seems to be quite sane. Corll provided him inspiration, and a program, but at some point the apprentice seems to have surpassed the master. “Wayne seemed to enjoy causing pain,” Brooks told police, a fact Henley readily admits.

“You either enjoy what you do—which I did—or you go crazy. So when I did something, I enjoyed it, and didn’t dwell on it later.”

It is not incidental that one of Henley’s favorite books is Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land. He likes Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, Harold Robbins, but his appreciation of Ayn Rand reveals that individuality resides in unlikely places: “I like The Fountainhead because the hero is a loner who does what everybody said he couldn’t do. In Atlas Shrugged, I liked the little utopia of the working people. They made their billions, but they weren’t going to be controlled by the government.”

Henley is the compleat American punk, the kid your mother warned you against becoming if you let smoking stunt your growth. He is also a perverted product of some of those frontier values, degraded in social transition, and emerging in the crime of the decade that seems too utterly contemporary to warrant further examination. Henley may represent the bottom of the trash barrel, but there is a disturbing resonance to his words.

“I feel remorse because I’m supposed to,” he says, and he is laughing. “That’s something I’ve tried to build in me. I don’t really feel about it, you know. I wished I hadn’t done it. I’m glad I got it over with, telling. I’m glad now I’m not hiding it, waiting, and Dean ain’t out there killing little kids. But as far as any emotion to it, there’s no heartfelt emotion.”

Visiting time has expired. Henley exchanges a few words with his attorney, and shuffles off down the hall. In a few weeks, he would be transferred to the Ramsey Unit of the Texas prison system.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books