This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The vastness of the sky and the breadth of the high dun and green plateau on which Marfa sits seem to diminish the encircling rim of mountains, pushing them back toward the horizon so that the whole vista appears unnaturally spacious, as if you were looking at it through a wide-angle lens. It is, after all, where Hollywood found Giant, a countryside of made-to-CinemaScope dimensions.

The town itself doesn’t challenge the grandeur of the land. As the seat of Presidio County, Marfa has the obligatory nineteenth-century stone courthouse; the dominant form on the man-made skyline is the metallic tower of the Godbold Feed Mill. The rest seems oddly temporary, a haphazard assortment of vacant warehouses, abandoned factories, and frame and stucco cottages in various stages of surrender to dust, weather, and neglect.

The Dia Art Foundation’s Marfa project, however, is supposed to be here forever. The star of the project is sculptor Don Judd, an art-world celebrity notorious for his cranky independence and determined iconoclasm. Backed by the family fortune of the Houston de Menils, the project has been nearly six years and more than $5 million in the making. When it is finished and opened to the public, perhaps next year, it will consist of more than one hundred large-scale, thoroughly modern sculptures, displayed in and around a dozen buildings scattered over 350 acres of Marfa real estate. It dwarfs any other museum exhibit or public art project of a similar nature.

The exhibits will focus exclusively on works by four of the most celebrated and influential artists of the last quarter century. Already begun are fifteen of Judd’s bleached concrete rectangular structures, made of slabs 2.5 meters high and 5 meters wide, proceeding in a precisely varied mathematical sequence across a quarter mile of pasture on the southwestern outskirts of town. Slick-sided, immaculately rectilinear, they are information-age megaliths intentionally designed to give no information. Next to them stand two old Army warehouses with new glass walls and etched concrete floors. On these floors sit long, gleaming rows of Judd’s aluminum constructions. The patterns of reflection and shadow created by their faultlessly machined exteriors vary with the rhythms of sky and land like some enormously complex, futuristic calendar.

In addition to Don Judd’s spare, pure geometries, the project will include John Chamberlain’s crushed-auto-body sculptures, already installed in a downtown warehouse that used to be the Wool and Mohair Building; a series of six fluorescent light sculptures by Dan Flavin, to be housed in renovated Army barracks; and, if all goes well, a building hung with prints by the late abstract expressionist Barnett Newman. There will also be a library and furnished apartments for the faithful who will make the pilgrimage to this modernist monument.

And there will be pilgrims, because in many ways the Art Museum of the Pecos—as it is somewhat ingenuously called—is to the avant-garde of the sixties and seventies what St. Peter’s was to the High Renaissance: a marriage of fully matured artistic vision with financial and cultural power, marking both the height of an empire and the beginning of its decline.

The vision belongs to Don Judd. He is the project’s architect and ideologue. In his mind the Art Museum of the Pecos is more than an aesthetic testament; it is a manifesto challenging the economic and institutional structure of the art world. And it just may be his shot at immortality.

The muscle behind the vision belongs to the Dia Art Foundation, a curiously secretive nonprofit organization founded by former dealer and transatlantic art personality Heiner Friedrich and funded almost entirely by the fortune of his wife, Houston heiress Philippa de Menil Pellizzi Friedrich. No modern precedent comes close to Dia’s purchasing power. In the ten years of its existence Dia has spent more than $30 million nurturing and acquiring the world’s most esoteric and advanced art. The foundation’s tastes are so rarefied that Andy Warhol is the rock-ribbed reactionary among its artists. Dia’s practice of lavishly patronizing a select group of cutting-edge artists has given the foundation the power not only to create what one critic calls instant Michelangelos but also to establish a new caste system among artists: those who are patronized by Dia, and those who aren’t.

But Dia’s ability to make art history is not the trouble in Marfa; money has always had that privilege. What worries Don Judd and more than a few other Dia critics is the foundation’s potential for neglecting and even destroying the history it creates. Recent events have increased Judd’s concern that Heiner Friedrich is bored with and is “going to dump” the project in which Judd has invested his artistic prime. According to Friedrich, that just isn’t so. Nonetheless, the completion and survival of this extraordinary project is threatened, if not by Friedrich then by the widening rift between artist and patron. And therein lies a strange tale of men and monuments.

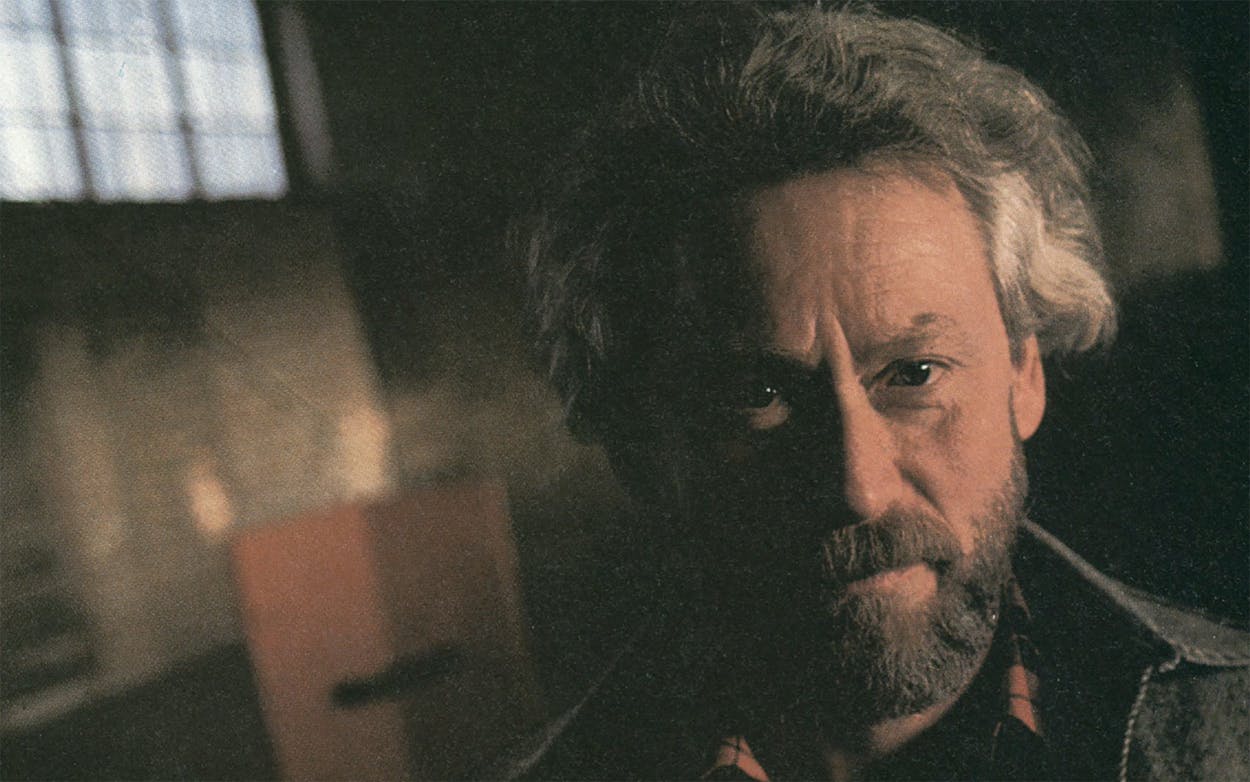

Like many sculptors, Don Judd has the look of a workman, thick-chested and stout-bellied, casually attired, with a scruffy salt-and-pepper beard, thick, curly gray hair, and lively, intensely blue eyes. He was born in Excelsior Springs, Missouri, in 1928, and despite his peregrinations since then, he retains an air of dry, middle-American pragmatism. He speaks softly in precise, unadorned sentences. In the art world, where verbal obfuscation is a marketing skill and sycophancy is as rife as at the court of Louis XVI, Judd is a warily admired anomaly, a man who talks plain and spares no one. He is not afraid to bite the hand that feeds; in an article scheduled for a fall issue of Art in America, Judd skewers, among others, Philip Johnson, the vaunted architect who has a prominent concrete piece by Judd on the grounds of his famed glass house in Connecticut.

Judd is a private and austere man. The measure of his success is not so much the things he owns as his ability to isolate himself from the rest of the world. Since 1968 his Manhattan home has been a seven-floor building in the heart of the SoHo district, a lurking gray bastion amid a cute and trendy neighborhood. Except for the kitchen, stocked with exotic food and liquor, very little of Judd’s building is given to human comfort, much less luxury; most of it is occupied by permanent, painstakingly arranged exhibits of works by Judd and his famous friends and colleagues, such as painter Frank Stella. Since 1972 Judd has also lived much of the time in Marfa, where he owns an entire downtown block right next to the Godbold Feed Mill. His compound has two warehouses filled with his own work—a self-financed effort separate from the Art Museum of the Pecos—two kitchens, a library, a studio, a vegetable garden, and a chicken coop. A fortresslike adobe wall surrounds the compound, and as one associate puts it, “The walls are suited to his temperament.”

For all that, there is considerable grace and warmth to Don Judd. He likes to play the generous host, and a few straight shots of tequila bring out a hidden charm rather than an underlying menace. He has remained close to the small circle of artists who emerged from obscurity along with him; his teenage son, Flavin, and daughter, Rainer, are named after Dan Flavin and dancer Yvonne Rainer. Judd has nothing good to say about his ex-wife, from whom he was divorced in 1978 after he won a bitter custody battle, but he has an affectionate relationship with the children. He is an opinionated man of impressive intellectual breadth. He received a degree in philosophy from Columbia University in 1953, later studied art history there, and supported himself as a critic for Arts magazine during the early sixties. His library in Marfa includes books on ancient and Renaissance art, geology, physics, history, desert plants, Texas Indians; he collects Navajo blankets, Sicilian puppets, Northwest Coastal Indian art, etchings by Rembrandt and Dürer.

Judd is the custodian of his own history as well—in rooms full of sculptures and stacks of old canvases from the fifties and rows of yellowed drawings. Unlike most artists, Judd seems to regard the sale of his art not as a desired end but as an unfortunate economic necessity. You get the strange feeling that he resents letting go, that he would like to keep everything he has ever made.

Judd has painted seriously ever since the late forties, but his rise to stardom did not really begin until about 1960, when, like a handful of younger painters, he began to free himself from the emotionally charged paint-splash legacy of Abstract Expressionism and to search for an art of greater simplicity. He started with a series of starkly symmetrical, no-nonsense geometric paintings: a single curved line against a monochrome field, or rows of evenly spaced stripes. Soon he extended the paintings into three dimensions by attaching aluminum wedges and iron flanges to the monochrome fields. Then in 1962 Judd made a relief out of wood, canvas, and galvanized iron pipe; it was so heavy and cumbersome that he left it on the floor. He followed that first freestanding sculpture with a series of simple geometric configurations.

But Judd’s most significant works were his boxes: wooden boxes with slots and troughs cut into them, boxes arranged in mathematically determined sequences. By the mid-sixties they were his trademark; he might make a single box out of Plexiglas or stack several Plexiglas or metal boxes at regular intervals on the walls or order them in neat rows on the floor. The boxes were clearly something new. Unlike traditional sculptures ceremoniously set on pedestals, Judd’s works sat right on the ground. Their hard, uninflected surfaces and precisely determined forms excluded any sentiment or rhetoric. As Judd remarked, “I wanted to get rid of all those extraneous meanings, connections to things that didn’t mean anything to art.”

Judd always opened up the boxes by leaving off the top or sides or using Plexiglas. Instead of hiding an inert core, as a traditional bronze or marble sculpture did, the interior volume of the box became an integral part of the piece. The boxes concealed nothing. Here was the absolute culmination of modernism, an art object that represented only what it was—form, volume, color.

With Judd leading the way, great pedestal-less geometric forms became to the sixties what drips and splashes on canvas had been to the fifties. That movement to cool, symmetrical geometric shapes in painting and sculpture became known as Minimalism, although most artists associated with the movement regarded the term as pejorative. There was a timely political message, sometimes intended, sometimes not, in all that mute geometry; its innate honesty appealed to a generation that was distrustful of its leaders and institutions. In a curious paradox, the absolute materialism of minimal art effectively conveyed the metaphysical mood and wary spiritual aspirations of the sixties.

Critics and curators enthusiastically embraced the new movement. Four years after Don Judd left his first relief on the floor, he was an international art star. In 1968 he was given a retrospective exhibition at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art; he was accepted into the stable of New York dealer Leo Castelli, the star-maker of American art; and he acquired a hot young European dealer, Heiner Friedrich of Munich.

By the early seventies Judd was searching for new worlds to conquer. He was growing claustrophobic in New York, and in the autumn of 1971 he looked around the southwestern United States and Mexico for a suitable retreat. After rejecting Baja California and New Mexico, Judd chanced upon Marfa. He liked its comparative emptiness, and he was especially pleased to find a number of large, abandoned buildings that could be purchased inexpensively.

For Judd, just as essential as getting himself away from the art world was getting his art away. Judd strongly believed that his new art demanded a new system of economic and institutional support. He and many of the artists of his generation disliked the role assigned to art objects by the old troika of collector-gallery-museum; they believed that their works had become little more than commodities, symbols of bourgeois cultural pretensions. As Judd later wrote, “The art gallery is the showroom of a business” and contemporary art museums “the necessary symbol of the city and the culture of the city all over the world.”

With fine blond hair brushed straight back, blue eyes behind wire-rim glasses, neatly clipped little moustache, and rock-jawed movie-star features, Heiner Friedrich is strikingly Aryan. Whereas Don Judd is taciturn but direct when he does speak, Friedrich is effusively diplomatic, with meticulously correct manners. His discourses are circular, metaphysically inflected; he seems to view them as important performances. Speaking in heavily accented English, he waves his arms like an orchestra conductor, occasionally slapping his desk with both hands for emphasis. Excerpts from a typical allegro: “There’s one Don Judd, one Michelangelo. . . . Without art, men would have been lost after five days of creation. . . . There is a tremendous sense of proportion and harmony in these works, not like Lebanon.” The effect is bewildering. Says one longtime associate, “I don’t know if you ever get a straight answer out of Heiner Friedrich, but that is because I don’t think Heiner himself knows.”

Friedrich was born in Germany during World War II. His father ran an equipment engineering firm and did well enough in Germany’s postwar boom to endow his son with an independent income estimated at well into six figures a year. Like Judd, Friedrich studied philosophy, but he left the University of Munich in 1962 without graduating. A year later, along with a partner, Franz Dahlem, he opened an art gallery in Munich. Friedrich made his name with the sale of a major collection of American pop art to a German collector, and he quickly developed a reputation for handling the most advanced work on either side of the Atlantic. Along with a few other European dealers and collectors, Friedrich was instrumental in establishing support for some of the leading American artists of the sixties—who were frequently prophets without profit at home. By the late sixties he was regularly jetting between New York and Germany and had become a transatlantic art business personality. In 1973 Friedrich moved to New York and opened a pioneering SoHo gallery.

Friedrich’s relationship with his wife, whom he married in 1978, has been described as “very sweet, very protective. He is the father and she is the little girl.” He first met Philippa de Menil at a party in Los Angeles in the late sixties, but their paths did not cross again until 1973.

Tall, slender, ethereal, Philippa, or Phipp, as she is known to her friends, was at the time married to Francesco Pellizzi, a dark-haired, serious, but quietly charming Italian anthropologist. Philippa has impressed acquaintances as caring, sensitive, and concerned, and her intimates think of her as incredibly fragile. She had both the temperament and the intellectual heritage to become quickly involved with Heiner Friedrich’s nascent vision, the Dia Art Foundation. Her parents, John and Dominique de Menil, were among the world’s leading private collectors of modern art, particularly Surrealism. They also had a tradition of go-it-alone projects, such as the Rothko Chapel in Houston, perhaps the outstanding and certainly the most original monument to Abstract Expressionism. Philippa shared her parents’ political idealism, ecumenical spirit, and interest in oriental religions. By the time she met Heiner Friedrich, she was already seriously studying Tibetan Buddhism and the Sufi Islam sect. And she had inherited something else that would be of immense importance to Dia: a fortune estimated at tens of millions—most of it in the form of stock in the family business, the Schlumberger oil drilling service.

The relationship between Heiner and Philippa was at first professional, but eventually it became personal. They married in upstate New York, in a mysterious, unpublicized ceremony that was performed in accordance with Muslim rites. For at least a year afterward Philippa continued to go by the name “Pellizzi.”

Today the Friedrichs and their young daughter (Heiner also has two teenage daughters from his first marriage) share a New York townhouse on swank East Eighty-second Street, literally a stone’s throw from Central Park and the imposing facade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They have redone the interior of the Federal-style structure with the precision and peculiarly sumptuous austerity that is characteristic of many of Dia’s projects—with aseptic white enamel walls colored by the fluorescent glow of a few strategically placed Dan Flavins, sparse neorustic furnishings, and minimal architectural detailing.

Heiner and Philippa are both devout Muslims. They attend the tekke, or dervish prayer lodge, of the Halveti-Jerrahi Order of New York. The tekke, on Mercer only a few blocks from Don Judd’s building, is done in immaculate Dia moderne, complete with lighting by Flavin—a somewhat unlikely environment for the Thursday evening performances of the dhikr, or remembrance of God, the bowing, swaying mystical ritual for which the dervishes are noted.

A third regular haunt for Heiner, though not for Philippa, is the office of the Dia Art Foundation. In an old building at 107 Franklin Street in fashionable TriBeCa, it contrasts sharply with the rest of the Dia empire. The reception area of the second-floor labyrinth is paneled in dark, dingy brown wood and floored with vintage vinyl tiling; the only color is provided by the faded blue bindings of a dusty old set of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Friedrich’s office is dominated by a nondescript round wooden table and a faded purple carpet.

The beginnings of the foundation go back to the early seventies, when, as a dealer representing minimalists, Heiner Friedrich shared many of their frustrations. As the most important new minimalist pieces became larger and were tailored to more-specific placements, either in their own rooms or warehouses or outdoors, they became more difficult to sell; you can’t take ten or twenty tons of concrete home and put it on a pedestal next to the sofa. Friedrich remembers the business of selling those works as a “very, very desperate job. All our patrons failed to go into it as far as we would like.”

Friedrich’s solution to the economic impasse was to create a private, nonprofit foundation, liberally funded, that could finance the most soaringly ambitious art without the slightest taint of commercial compromise. The name of the foundation would be “Dia,” a term of Greek derivation, whose meaning seems to vary with the subtle political requirements of the moment. According to Friedrich’s latest analysis, “it is a very humble term, a transitory term. It means the transitory ability that each person has in life.”

In June 1974 the Dia Art Foundation was incorporated in New York and was awarded not-for-profit status. The board of directors consisted of Philippa Pellizzi as president and Heiner Friedrich and Helen Winkler (a longtime Menil employee) as vice presidents. In its charter the foundation pledged itself to “primary emphasis on those projects which cannot obtain sponsorship or support from other public or private sources because of their nature or scale.” It was also determined that “the Corporation shall be of perpetual duration.” In return for such commitment Dia was exempted from income tax, sales tax, and most real estate taxes.

Dia spent nearly $80,000 in 1975, its first full year of operation. The foundation’s first completed project was a relatively unremarkable work by Dan Flavin, who was already a well-established artist. It was a permanent installation of fluorescent light fixtures set in the courtyard of the Kunstmuseum in Basel, Switzerland. The next year, Dia spent nearly half a million, much of it for projects that would not come to fruition for some years. In 1977 Dia spent over a million. This time Dan Flavin lighted three 1000-foot-long platforms at Grand Central Terminal in New York.

The foundation’s two most sensational projects in those years were by an exceptionally reclusive artist named Walter De Maria, who had not even shown in New York since 1968. During 1977 De Maria completed The Lightning Field out on a barren, scrubby plateau in west-central New Mexico. The piece, one mile long and one kilometer wide, consisted of four hundred thin stainless steel poles placed in parallel rows. In the summer of that same year, at a quadrennial exhibition of avant-garde art called “Documenta VI,” workers operating on instructions from De Maria drilled a hole one kilometer deep in a park in front of the Museum Fridericianum, an art museum in Kassel, West Germany. Into the hole was sunk The Vertical Earth Kilometer, a solid brass rod two inches in diameter and one kilometer long. The top of the rod was flush with the surface of the earth and surrounded by a red sandstone plate two meters square.

Despite the considerable excitement that the De Maria projects aroused among the cognoscenti, Dia failed to follow up with any major projects in 1978. But by then Dia’s biggest, most expensive project had already been conceived: Marfa.

The planning for the Marfa project was noticeably lacking in drama and even in firm decision. The first meeting between Judd and the Friedrichs was in June 1978. By then Friedrich had been selling Judd’s work in Europe for ten years; he had also shown Judd’s work in his New York gallery in 1977 and was planning another show for the following fall. Friedrich and his daughters had visited the Marfa compound for the first time a few weeks earlier, and he had been amazed by the extent of Judd’s installations, over which the artist had labored for several years. Now Friedrich and Pellizzi suggested in general terms that Dia sponsor an even more ambitious project in Marfa.

It seemed like a glorious, even historic union. Though Judd and his would-be patrons were not close friends, they had similarly austere and demanding tastes in art. They also shared a belief in the importance of working outside the established system of galleries and museums. And despite their maverick intentions, both Judd and Dia were already powerful art-world institutions.

In the following months, the project was often discussed informally in conjunction with plans for Judd’s upcoming October exhibition at the Heiner Friedrich Gallery. That fall Friedrich and Pellizzi came to Marfa for a few days on a real estate shopping expedition. Judd took them to see Happy Godbold, owner of the Godbold Feed Mill and Fort D. A. Russell, a defunct Army post that sprawled over several hundred acres on the outskirts of town. Godbold, who was particularly taken with Philippa, recalls that they negotiated the sale of the fort’s two ordnance warehouses while casually sitting around a table. Dia also purchased the 24,000-square-foot Wool and Mohair Building from Bill Quick, a local realtor. At the time, Judd was satisfied that the three buildings had enough space for the works he envisioned.

Renovation of the buildings soon began, while in New York Judd’s private curator, Dudley Del Balso, worked out the logistics of fabricating Judd’s aluminum pieces. A contract was signed on January 5, 1979. In it, Dia and Judd committed themselves to 13 twenty-foot-long horizontal aluminum wall pieces; 3 vertical metal wall pieces, each composed of 10 thirty-one-inch-high units; 2 stainless steel floor pieces, each consisting of 5 fifteen-foot-long channeled steel rectangles; 25 large milled aluminum boxes; and a series of outdoor concrete pieces of unspecified size.

Given the cost of fabricating the aluminum pieces to Judd’s exacting standards (each of the milled aluminum boxes cost $5000) and the outlay for real estate, the Marfa project was already Dia’s most expensive. To pay the bills, the foundation sold off Schlumberger stock donated by Philippa; 56,300 shares brought slightly more than $4.7 million in 1979. That same year the foundation spent nearly $4 million on projects, art, equipment, and real estate. Only one major project—The Broken Kilometer, by Walter De Maria—was completed during 1979. The piece, a companion to the Kassel installation, consisted of five hundred brass rods, each two meters in length and two inches in diameter, placed on the floor in five parallel rows of one hundred rods each. It was permanently installed in a building that Heiner Friedrich had once used as a gallery.

The next two years were boom years for the oil drilling business and for Dia. During 1980 and 1981 Dia raised $16.6 million on the sale of 186,000 shares of Schlumberger, again donated by Philippa. Over the same period Dia paid out almost $19 million. By the end of 1981 Dia owned $12 million worth of art and more than $13.5 million in real estate. The foundation’s administrative expenses, which were now close to $4 million a year, included such line items as “Documentation and preservation of materials concerning the Foundation’s activities, and dissemination of this information to writers, scholars and the general public—$41,670,” and “Acquisition, direction and control of Foundation real estate—$178,441.” Dia owned at least seven buildings in New York City outright or in part, and its staff had grown to about eighty people.

But in terms of art, there wasn’t much to show for all the millions spent. Dia did sponsor a modest series of performances in New York City and a few small exhibitions of European artists in Cologne. Perhaps the most significant project was Walter De Maria’s New York Earth Room. The permanent installation, in a second-story SoHo loft, featured 140 tons of earth spread to a depth of 22 inches over 3600 square feet of floor space.

Rather than sponsoring projects, Dia seemed to be stockpiling art and real estate to house it. The foundation had begun to conceive of its efforts on a grand scale; with the Marfa project as inspiration, one-man museum spaces were envisioned for Andy Warhol, abstract painter Cy Twombly, John Chamberlain, German avant-gardists Imi Knoebel and Blinky Palermo, and one of the most important artists then working in Europe, the madcap German conceptualist Joseph Beuys. Each space was to be permanently stocked with works from the inventory that Dia was amassing. They would be irrefutable evidence of Dia’s challenge to the art establishment.

Marfa, the prototype and the flagship of that daunting armada, was treated liberally; more than $2 million was poured into the project in 1980–81, much of which went for real estate. In the summer of 1980 Friedrich and Pellizzi started negotiations to buy the barracks and equestrian arena at Fort D. A. Russell and 340 acres of land adjacent to the fort. Judd tried to discourage the purchase; he argued that it would make far more sense for Dia to build a new structure perfectly suited to the art it was intended to house, rather than renovating abandoned barracks. He lobbied heavily for something in a “cleaner situation out on the range.” But Friedrich remained adamant. “Don Judd wanted to build it out in some place no one could get to. I represented the public interest.”

That conflict was but one of many between artist and patron. Judd’s irritation with Friedrich and the foundation had been growing steadily over the past year and a half. He was displeased by the performance of the local woman whom Friedrich had hired to manage the project. He had also begun to feel that he was underpaid, considering that he was designing the renovations to the buildings and working on the fabrication of the sculptures as well as supervising the actual construction of pieces.

In March 1980, shortly before his contract with Dia came up for renewal, Judd erupted and threatened to abandon the project unless new terms were arrived at. He wanted not only more compensation but an expansion of the original concept as well. An epic clash of egos was shaping up: Judd was determined to squeeze as much as he could out of a patron whose wealth now vastly exceeded his initial expectations; Friedrich was determined to exact the obedience that his largesse undoubtedly warranted.

Finally Del Balso, who had taken on much of the burden of planning and coordinating the project, flew to Texas to meet with Judd and see what could be worked out. Over the next three days Del Balso spoke with various lawyers and ultimately to Friedrich. Judd was still so upset that he couldn’t speak to Friedrich, but he communicated his demands via Del Balso. “Tell him it’s one hundred pieces or I quit,” Judd shouted at one point, referring to the milled aluminum boxes; 25 had originally been stipulated in the contract. Friedrich acceded, committing another $375,000 to the project on the spot.

More than a year later, in April 1981, the new contracts—prepared on Judd’s behalf by an attorney with a prominent Manhattan law firm—were signed. Three separate documents covered Judd’s functions as architect, artist, and supervisor. The contracts were carefully detailed, specifying such matters as authorization and ownership of photographs of the project. The agreements indicated exactly the works to be built. There was to be a series of large concrete pieces by Judd as well as works by Chamberlain, Flavin, and Barnett Newman. The administration of the project was left under joint control of the artist and the foundation.

Also included were two key clauses binding the Dia Art Foundation to perpetual ownership and maintenance of the works, at Judd’s discretion. Judd had feared that the works would be neglected or, worse still, that Dia, now owner of a huge inventory of his pieces, would sell it en masse, seriously depressing market values for years, if not permanently. Eventually, Judd’s compensation was set at $16,000 a month through 1982 and $17,500 a month through 1984, an amount comparable to what he could have earned in the same period by selling his work through galleries.

During the Christmas season of 1981, Judd was invited to a dinner at the Friedrichs’ newly decorated townhouse on East Eighty-second Street. The ground floor was almost bare, while upstairs were two rooms, one furnished with cushions, a Dan Flavin, and an oriental rug, the other with a single wooden table and harsh, upright wooden chairs. “It looks like the Turkish headquarters of the Nazi party,” joked one of the guests, though not within earshot of the hosts.

A number of Dia’s artists and employees attended, including Andy Warhol, Chamberlain, and Judd. So did Heiner’s ex-girlfriend Thordis Möller. An envelope was set on each person’s place at the table, and before dinner Judd peeked into his and found that it contained cash. As Judd tells the story (one which Möller denies), Möller, sitting between Judd and Chamberlain, picked up Judd’s envelope and counted out loud; it came to $2000. Then she took Chamberlain’s envelope and, after counting silently, announced the amount in it: $1500. No further comparisons were made.

Dia’s largesse could not continue indefinitely. The drilling boom was slowing, and by mid-1982 the price of Schlumberger stock had been falling for more than a year. Alarms were going off throughout the Dia empire. In New York, Robert Whitman, a performance artist who was one of the first artists patronized by Dia, tried to organize a meeting of the Dia artists to discuss the situation. Whitman felt that he was in danger of being marooned if his only patron couldn’t come through. But the meeting never materialized. Meanwhile, after four years and more than $3 million, Dia began requesting monthly budgets for the Marfa project.

By year’s end Dia had spent another $5.2 million; only about $2 million of that went to acquire assets, most of them in Marfa. The rest went to cover Dia’s staggering administrative expenses. Dia was able to raise only about $1.5 million on the sale of more than 29,000 shares of Schlumberger, less than $50 a share; previous sales had brought from $75 to $110 a share. Rather than sell off undervalued stock to meet operating expenses—surely these depressed prices are temporary, went the thinking at the foundation headquarters—Dia borrowed $3,871 million from Citibank. The loan was secured by 140,000 shares of Schlumberger hypothecated by Philippa.

The uncertainty over when and if the price of Schlumberger would recover only added to the tension between Judd and Dia. Despite the detailed new contract, the relationship between artist and patron continued to be difficult. A second project manager had turned out to be no more acceptable to Judd than the first, and he was now growing disgruntled with a third manager, a Dia staffer from New York. Still, progress was made, and by the end of 1982, about 35 pieces from Judd’s aluminum series, 7 of the outdoor concrete pieces, and nearly 20 other works had been completed. A dinner at Judd’s New York studio in the spring of 1982 was stormy, with Judd denouncing Friedrich as wasteful and incompetent. A lunch that fall in Marfa was peaceful. Judd’s Christmas bonus of $2000 came by mail, but this time Judd sent it back.

In January 1983 the two men met at Judd’s SoHo studio. Judd was led to understand that everything was still on schedule. But when Friedrich returned to Marfa in February, things had changed. He told Judd at great length of his money problems and informed him that the Flavin installations agreed upon for Marfa were to be postponed. The meeting ended in a bitter exchange. In early March Judd got more ominous news. A letter from the foundation arrived suggesting that his compensation be reduced. A week later the final bombshell dropped: another letter from Dia, this time proposing that Dia transfer its assets in Marfa to a new, independent foundation.

Judd soon discovered that his project was not the only one from which Dia wanted to withdraw; the foundation’s lawyers are working on what is essentially a complete breakup of the Dia art empire. If it takes place, all or most of Dia’s art holdings will be divided among separate foundations, each of which will be wholly responsible for its own support and continued existence.

Not surprisingly, Judd was deeply upset by Dia’s plans to withdraw from the project. Although Friedrich assured him in a letter that Dia would transfer “most of the assets which it now holds in connection with the Marfa project” to the new foundation after it had “proved its competence in all areas and shown its ability to maintain the assets,” Judd was extremely dubious that such a transfer would take place as promised. Judd figured that by agreeing to the new foundation, he would be letting Dia have it both ways. He would be responsible for finding the money to complete and perpetually maintain the project; meanwhile, Dia could retain ownership of the property and the art.

Judd’s lawyer wrote Friedrich, rejecting any reduction in compensation and promising to review the proposed transfer of the project. In response, Dia’s in-house counsel Naomi Newman sent a seven-page memo detailing the steps necessary to form an independent foundation. “It is the opinion of the directors,” the memo stated, “that each of the projects Dia has sponsored and fostered would be better served—as would be the public—if these projects became independent tax exempt organizations.” The decentralization plan has since become a publicly acknowledged Dia policy. “We are no longer expanding,” says Friedrich. “The mother cannot hold her children to her breast forever. She must send them out into the world.”

Shortly after the exchange of letters, Judd flew over the Friedrichs’ Mesquite Ranch, south of Marfa, in a small plane. He was surprised and infuriated to see bulldozed roads and clearings and a complex of brick-and-concrete cottages fronted by circular, raised brick-and-concrete pools. If money was a problem, who was paying for this? Judd recalled telling Friedrich, “If you want to run something, why don’t you buy yourself a town?” Friedrich had replied, “We have something else now.” Apparently this was it.

Exactly what is going on out at the Mesquite Ranch is a great secret; according to Judd, Friedrich asked a Dia employee in Marfa to dissuade the foundation’s vice president Helen Winkler from seeing the ranch on a recent visit to Marfa. Friedrich responds to inquiries about his ranch with a curt “That’s private,” but he does not deny that he is building a religious community or retreat.

As befits a true monument to our times, the fate of the Art Museum of the Pecos may now lie in the hands of lawyers and judges. Don Judd says he is prepared to sue for breach of contract if the various projects stipulated in the April 1981 contracts, particularly the postponed Flavin installations, are not finished as planned. Judd also intends to hold the foundation to its contractual commitment to perpetual ownership and maintenance of the works, an expensive obligation that Dia could evade by assigning ownership to an independent foundation.

Not all of Dia’s artists share Judd’s anger over the foundation’s actions. Many remain grateful for the patronage that has in a number of cases made their careers. “When you make your choice, that’s what you do,” says Robert Whitman. “It’s not often that you have a choice that affects your whole life, but most artists never even have that choice. They struggle through life, and what do they end up with? A bunch of paintings.”

Yet, broader questions about Dia’s involvement and responsibility remain to be answered. In the artistic milieu in which it operates, Dia is ponderously, perhaps dangerously rich. Relatively speaking, only the Getty Trust, which runs the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu and controls a $2.1 billion endowment, has a comparable ability to buy just about any and every significant piece of art that falls within its scope. But because the Getty is a historical museum, it can change only the history of art collecting, not the history of art.

Dia, on the other hand, has the power to create the cultural equivalent of a worldwide ecological disaster. Having acquired vast inventories of works by some of the most original artists to emerge in the past two decades, Dia has in effect proceeded to conceal the works, not only from the general public but also from other artists. Right now most of Dia’s collection is crated in a warehouse on West Twenty-second Street in New York, and Dia’s one-man museums seem to be on indefinite hold. The art that is seen has always been the most important influence on the art that is made—the best artists spend much more time looking at and learning from the work of their colleagues, both the quick and the dead, than they do worrying about the pronouncements of critics—and Dia has inadvertently removed a good deal of the most stridently innovative work of recent years from that process of cultural evolution. Whether or not Dia dissolves, if it fails to provide some way of returning the art to the culture from which it came, much of the art of our times is likely to be lost, to the present and to posterity.

If the one-man museums do materialize, their independent maintenance is going to be difficult, especially now that the proliferation of small nonprofit arts organizations is spreading the government and corporate dole ever thinner. As Dia acknowledges in its corporate charter, the artworks it has sponsored are those that “cannot obtain sponsorship or support from other public or private sources because of their scale or nature.”

Don Judd has plenty of time to think about all that as he struggles to realize his vision in Marfa. He knows as well as anyone that history, particularly the history of art, is much more a matter of what remains than what was. At best the completion of the project will be delayed by his broadening differences with Heiner Friedrich, who seems committed to pulling out. “We can foresee only a limited life for the foundation,” Friedrich says, “but we believe that these projects are powerful enough to go on into history.” Judd, though, is equally committed to his vision of the Marfa project. He promises “to finish it if I have to live out here in a pickup.”

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics

- Sculpture

- Longreads

- Donald Judd

- Marfa