Kermit Oliver is perhaps the least well-known of the great living Texas artists, and that’s largely by his own design. Though his early career put him on a path to art-world prominence—in the early seventies, he was the first Black man to be represented by a major Houston gallery, and a decade later he became the first American artist to design scarves for Hermès—Oliver abandoned Houston in 1984 for a quieter life in Waco and a job with the U.S. Postal Service. His mature career as a painter has been marked by reclusiveness and monklike craftsmanship in his home studio. Several of his works have never been displayed outside his house.

Walking into the expansive “Kermit Oliver: New Narratives, New Beginnings,” on view at Art Center Waco through December 17, feels like stepping through a portal to a more rarefied plane of reality and perception, a place where Oliver has been living on his own these past few decades, which we are only just now permitted to visit. It’s all the more disorienting to find this in Waco, a city not known for its thriving art community.

The effect, however, is enchanting. Art Center Waco’s brand-new exhibition space, a down-to-the-studs renovation and a relocation from its crumbling former home at McLennan Community College, is on South Eighth Street near the Silos shopping complex. It portends a meaningful role for visual art as part of Waco’s Magnolia-driven downtown revival. Meanwhile, on Oliver’s canvases, even more farfetched scenes play out.

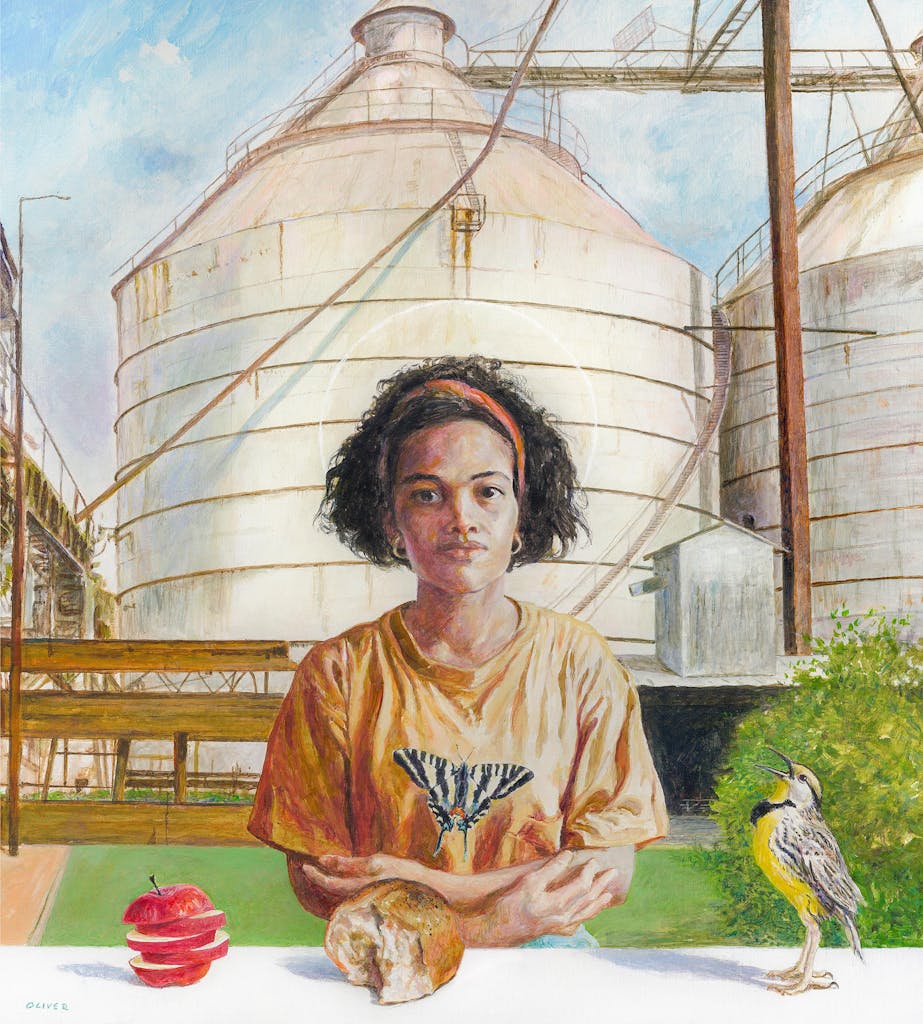

Oliver borrows and reinvents allegorical styles from premodern painting, from medieval saints’ icons to Renaissance tableaux to Pre-Raphaelite pastoral idylls. He is also influenced by John Biggers, his teacher at Texas Southern University in the sixties, whose epic, mythic sensibility informs the work so many Black artists who came of age under his tutelage in Houston. Oliver is especially concerned with the relationship between people and animals, including farm animals such as the ones raised for slaughter in the rural South Texas town of Refugio, where he grew up. The flat agricultural landscape of the Texas Gulf Coast region shows up again and again in his backgrounds. Meanwhile, the symbolic and surreal foreground action of Oliver’s story paintings leads us to contemplate the braided coexistence in nature and in human life of moments of birth, death, sacrifice, and regeneration.

Many of Oliver’s paintings move Black figures, sometimes likenesses of himself or his family members, through these stations of life. Consider his striking 1997 painting Orpheus, featuring an accordion player with a wandering eye staring out at the viewer from a pitch-black background where a massive tiger pounces. The title references the hero from Greek mythology, best known for his passage through the underworld to recover his lost wife, but also famous for playing his lyre to tame wild animals—a common subject in seventeenth-century European painting. Here, Oliver has simplified that typical scene to just one animal, the tiger, who seems set on tearing into Orpheus. The musician will have to lift his instrument and play if he hopes to tame back the abyss. The musician’s gift of transient beauty is further symbolized by ripe flowers and a book of illustrations of fruit at the bottom of the frame.

Often, there’s a sense in Oliver’s paintings of imminent or recent death, as in Nisan Morning (2004), which features an animal carcass hanging between theatrical curtains, or Holofernes (1983), which presents a disembodied head on a platter next to a tray of peaches. (Both painting titles are from scripture—Nisan is the month of the Hebrew calendar when the world was created and when Noah’s flood subsided, and Holofernes is an Assyrian general beheaded by Judith.) Other paintings like Peaceable Kingdom (1989) are definitively bucolic, with a Renaissance angel overhead, a child at the center, and various pairs of natural enemies lying down beside each other—the lioness with the lamb, the wolf with the turkey, the dog with the cat and duck, and so forth.

Some of Oliver’s life story was told a decade ago in this magazine. He’s a private, religious man who witnessed his son Khristian be executed by the State of Texas in 2009 after a decade on death row. Oliver’s paintings do not speak plainly about that unimaginable grief, nor about any of his autobiographical experiences. We may choose to read into them, but the greater sense one gets from the work is that of a symbolic road map for any viewer who wants to make sense of his or her own knotted life on earth, with its inevitable personal moments of beauty, tragedy, void, and transcendence.

Oliver is a serious painter with his eye on something beyond the fickle attention of the fast-moving art world. From his home-studio research, he’s acquired broad and handy knowledge of Texas flora and fauna, which show up everywhere in his paintings and in his ongoing work designing Southwestern-themed scarves for Hermès. He also has developed a profound fluency in art history and the symbolic language of the Bible and antiquity. References to these symbols are everywhere in his painting titles, such as . . . And I Saw Heaven Open and Behold a White Horse (2002), a line from the Book of Revelation, or No Sacred Moly (2014), which depicts a sort of pig-man and refers to the herb that Odysseus takes to protect himself from being transformed into swine by the enchantress Circe. One gets the strong impression that these ancient and long-abiding cultural reference points are not mere surface play for Oliver—not just clever, hollow nods to give a patina of learnedness, as can often be the case when the classics are referenced in contemporary art. On the contrary, there’s a sense that the more time we spend with Oliver’s work, the more hidden meanings will reveal themselves to us.

The Waco exhibition, guest-curated by Susie Kalil, forces viewers to circulate around movable walls and in and out of side galleries, so that we are always re-encountering paintings in our peripheral vision as we move from piece to piece. It’s a clever way to get us to notice symbols that recur across Oliver’s work and to return to paintings that we might experience more powerfully upon second viewing. Kalil, whose definitive book on Dallas artist Roger Winter we reviewed last year, is working on a similar project now with Oliver that promises to help uncover some of the meanings in the work that are inevitably lost on a casual viewer. Here’s hoping it will carry the argument for Oliver’s enduring relevance far beyond the confines of his adopted hometown—even if he prefers to stay put there.