This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Late last summer, preparing for his eleventh season, Dallas Cowboys safety Charlie Waters backpedaled doggedly in the second quarter of an exhibition game in Seattle. Though his left ankle was heavily taped and “blocked” with novocaine, it still bothered him. The Seahawk receiver ran deep, then pulled up and turned back. Favoring his bad ankle, Waters seized the opportunity for an interception. He planted his right foot against the King Dome AstroTurf and made his cut, but he shifted too much weight. Had his short cleats skidded, that would have relieved the strain. His taped right ankle withstood the torque, but a ligament in his knee ripped loose. Waters was out for the year, on a play in which he neither struck nor took a blow.

The noncontact injury that crippled Charlie Waters in August was no isolated incident. Before the end of September, AstroTurf footing also claimed the knees of rookie Green Bay runner Eddie Lee Ivery, the Packers’ top draft choice, and Cincinnati receiver Billy Brooks, an Austin native and former Oklahoma Sooner. The subject of injuries on artificial turf has caused a heated labor-management dispute in the National Football League, and the debate has begun to filter down into amateur athletics as well.

Without the invention of artificial turf, Charlie Waters would never have played a pro game in Seattle. AstroTurf and its various synthetic competitors enabled complete enclosure of athletic stadiums from the weather. Without domed stadiums, the NFL wouldn’t have granted an expansion franchise to a city where it rains constantly. The same kind of injury as Waters’ has in fact long been a hazard on Sunbelt grass. Before rubber-cleated “soccer shoes” became popular, football players wore long, steel-tipped cleats that often hung in thick-rooted Bermuda, placing strain on ankles and knees. Ironically, the apparent elimination of that problem provided early AstroTurf salesmen with a claim of superior safety. Promoters of artificial turf have now fallen back to the next line of defense: it’s no worse than the grass and dirt football is played on. Is that answer sufficient? Conceding that artificial turf is necessary in some locales, is it as safe for the athletes as it should and could be?

“Before my injury, I was an advocate of artificial turf,” Waters told me. “A professional breaks the game down into variable and constant factors. The footing on natural grass is a variable, while on artificial turf it’s a constant, so that’s one less thing to worry about. AstroTurf has a grain like a golf green, and like the golfer you make a point of knowing which way it lies. If you’re running with the grain you know you have to round your cuts. If you’re running against it, you know the footing is going to be tight. So in a way the injury was my own fault: I should have known.

“Yet I also know that if I’d made the same cut in the same shoes on grass, my knee wouldn’t have left me like that. Maybe I’ve had too much time to think about it. My forte has been the ability to make the move when I see mentally that it’s time, without having to worry about bodily hangups. Am I still going to be able to make those moves?”

The synthetic age arrived on athletic playing fields when the newly named Houston Astros’ outfielders started dropping more fly balls than usual. The first tenants of the Astrodome, the Astros played on a field of thin-bladed grass specially developed by Aggie scientists to be grown indoors. The hybrid lawn was holding its own, though it was hardly lush. But when the Astros and visiting Braves and Phillies looked upward, daylight coming through the plastic panels in the roof of the dome was like a flash of sun on snow. The panels were soon painted and, deprived of light, the grass began to die.

The management of Texas’ first baseball/football stadium resolved the emergency with an appeal to technology. The corporate parent of AstroTurf is Monsanto. Headquartered in St. Louis, it employs 60,000 people and claims $4 billion in annual sales. Monsanto had initiated artificial-turf research during the fifties with the assistance of the Ford Foundation, which had financed a study suggesting that inner-city children reared on concrete playgrounds grow up athletically deprived (except in basketball, one supposes). When the Astrodome grass began to fail, Monsanto already had an experimental field at a Rhode Island prep school. In the language of its manufacturer, the invention consisted of a half-inch pile of monofilament nylon ribbon knitted into webbing made from heavy-duty polyester tire cord, a five-eighths-inch pad of elastomeric foam, and a bed of asphalt mixed to local highway specifications and poured over a system of drainage pipes.

Monsanto had the Houston infield in place by the end of April, and in late September that first year—with the Astros 23 1/2 games out of first place—the University of Houston opened its 1966 football season against Washington State in the Dome, on a field as green as the play grass in children’s Easter egg baskets. All systems were go with AstroTurf—a fast, durable, synthetic field rolled out like magic carpet and stitched, as its promoters loved to say, “by more than three miles of zippers.”

The new surface took over rapidly. The Oilers and Cowboys play in stadiums that can never grow grass. Grass disappeared from the eleven Southwest Conference stadiums (both SMU and Arkansas use two) so fast that it is now almost forgotten. When Fred Akers’ Longhorns traveled to Missouri this September, the UT football team had not played on natural turf in five seasons, since the 1974 Gator Bowl. Hearing the anguish over the slippery Missouri rye, one might have thought the boys were being asked to make their cuts on Mississippi mud.

Darrell Royal used to say that the coaches who complained about artificial turf were the ones who didn’t have it. Real merits aside, synthetic fields became a prestige item, the trump card of recruiters. At its cheapest, an AstroTurf football field never cost less than $250,000—a large gulp for athletic directors with fewer resources than Royal. (Baylor financed its AstroTurf with an appeal to alums to “buy a yard” of the new field.) Still, the unanimous Southwest Conference message was not lost upon institutions like UT–El Paso, UT-Arlington, and Blinn Junior College, nor upon public school districts with enough wealth, stadium use, and football zeal to justify the cash outlay. Elected school boards have now bought synthetic fields for twelve high school stadiums: one each in Wichita Falls, Plano, Garland, Highland Park, Pasadena, Spring Branch, and Aldine, two in Mesquite, and three in Dallas. The Texas Rangers’ Arlington Stadium, spared the punishment of football, is now Texas’ only major athletic arena with a natural-grass field. Like Jett Rink, we just can’t help believing the petrochemical industry is a giant step up from agriculture.

Monsanto’s success with AstroTurf naturally inspired competitors, many of whom ran into unexpected problems. Poly-Turf perished because the New England Patriots’ Schaefer Stadium field turned turquoise; the Orange Bowl PolyTurf transformed the Miami Dolphins’ games into fall-down slapstick. Tennessee’s Tartan Turf turned black. But despite its early color difficulties, Tartan Turf proved a worthy competitor. Made by St. Paul’s 3M Company—better known for Scotch tape—Tartan was designed to resemble plush carpet, not synthetic grass. After experimenting with different cleats and shoes, some players concluded wet Tartan Turf provided better footing than wet AstroTurf. Tartan’s Southwestern clients were impressive—Oklahoma, TCU, and the Dallas Cowboys. But when material costs skyrocketed because of the 1974 oil embargo, 3M discontinued marketing the turf in favor of more profitable tennis courts and basketball floors. For more than a year Monsanto enjoyed a monopoly. Though new competitors have emerged, Monsanto’s AstroTurf division attained the dream of all free enterprise: like Kleenex and Jell-O, its brand name became the generic.

Outside Texas, AstroTurf’s major competition now comes, deservedly enough, from natural grass—or almost natural grass. Developed at Purdue by faculty agronomist W. H. Daniel and stadium groundskeeper Melvin Robey, Prescription Athletic Turf (PAT) sods deep-rooted grass in heat-controlled sand that is laid on a grid of plastic pipes connected to drainage pumps. PAT won contracts in Denver’s Mile High Stadium and the post-Poly-Turf Orange Bowl; and Robey’s offshoot company, SportsTurf, gained a foothold last year when the City of San Francisco decided to remove the AstroTurf in Candlestick Park. But the jury is still out on the reliability of sand-based turf. When Purdue’s own PAT field was resodded, the grass almost failed because of too much water and fertilizer, resulting in shallow roots, huge divots, and sloppy footing. Last summer in San Francisco, bay winds stripped the sandy base paths almost down to the plastic pipes. PAT’s most ambitious football undertaking has been RFK Memorial Stadium in Washington, long renowned for rainy autumns and the worst natural-grass field in the NFL. “I’ve played up there when they dyed the field for television,” Dallas’s Harvey Martin told me. “No grass—it was painted dirt. After a few plays, your arms and fingers would come up green.”

For the moment, AstroTurf salesmen can claim a virtual standoff in the price contest between their product and sand-based grass. Installation of a synthetic football field now costs about $300,000, but that doesn’t include the earthwork and asphalt. On the other hand, maintenance costs are virtually nil. If the clients protect their carpet from sunlight with a tarp, they should get ten years of service at a total cost of about $500,000. The installation price of sand-based grass is only $200,000, but the maintenance cost for water, fertilizer, and labor runs about $30,000 a year. Over the same ten-year period, the total for sand-based grass is theoretically $450,000.

But AstroTurf is that cheap only because another competitor invaded the synthetic market. SuperTurf originated at Cameron University, whose modest stadium accommodates the schedules of its NAIA independent Aggies and three Lawton, Oklahoma, high schools. The head coach at Cameron in 1974 was John Linville, formerly a Rice assistant. Linville favored artificial turf for its durability and recruiting advantages, but Tartan had withdrawn its product and AstroTurf quoted a price of $400,000. One of Linville’s players was the son of Dallas asphalt contractor Bill Paschal. Upon hearing of Linville’s woes, Paschal inspected a synthetic field at Murray State in Kentucky and concluded he could do the job himself if he could just buy the materials. A curt voice at Monsanto informed Paschal that AstroTurf did not deal with subcontractors and that all previous imitators had gone broke. The Dallas businessman exclaimed, “You mean you’re the only artificial-turf company in the whole United States?”

Paschal found a supplier in Chevron, whose sun-resistant, grasslike Polyloom II already enjoyed popular use on freeway medians and burial sites. American Klegecell made the pad from plastic resins. After $300,000 had been raised by Cameron University, the Lawton school district, and a local oil foundation, the surface was installed during the summer of 1975.

As Paschal promised, Cameron’s SuperTurf held up. Meanwhile, Linville applied unsuccessfully for the next head coaching vacancy at Rice, then accepted Paschal’s invitation to become vice president of sales for the new SuperTurf company in Garland. SuperTurf cast low bid for high school stadium jobs in Plano and Mesquite and opened a lucrative new market in the Middle East, where water shortages and alkaline soil had confounded the Arab love of soccer.

SuperTurf’s major break came when there was a falter in the negotiations between Monsanto and the New England Patriots, who were faced with having to replace their blue Poly-Turf. SuperTurf was awarded that job at the urging of Patriots coach Chuck Fairbanks, familiar with the Cameron experiment through his former ties to OU. Awarded NFL credibility, Linville attacked his large competitor’s exposed heel: players’ complaints of more injuries on AstroTurf. Calling SuperTurf the “tough playing surface that isn’t tough on athletes,” Linville claimed the SuperTurf pad provided much more impact protection than Monsanto’s. He argued that because his product’s tufted fibers were denser and resisted ultraviolet deterioration, they would spare players the abrasions so common on AstroTurf. In addition, since his fibers stood upright and thus had no “grain,” they would eliminate the excessive traction—a hazard Linville termed “foot fix”—that crippled Charlie Waters.

Like any product in command of its market, AstroTurf has many happy customers. Despite ardent courtship by SuperTurf, the Wichita Falls school board stayed with Monsanto when the time for its “second generation” of artificial grass arrived. The board had purchased AstroTurf for its new Memorial Stadium back in 1970, about when most of the Southwest Conference colleges made the decision. Wichita Falls got nine years from the state’s first high school artificial turf, four years beyond the product warranty. When last spring’s tornado scored a direct hit on the stadium, the asphalt had already been bared—which spawned persistent rumors that the wind had sucked the carpet loose. Despite the horrendous financial strain placed on the district by the tornado, administrators didn’t bemoan the cost of the new AstroTurf.

Athletic director Bill Jeter echoed the Monsanto sales pitch: efficient land use, maximum stadium utility. “We play games on it every day but Sunday, from the seventh grade on up, and our only maintenance is washing it down occasionally. When we had grass, if we got rain in September, by November our field was nothing but a bald knob.”

Rider High School coach Morris Mercer had no reservations either. “For one thing, it’s cut way down on our laundry. When I’m sitting here Friday afternoon watching the sleet and snow, it sure is a joy to know we’ve got a field to play on. I think we get more kids out for football because of it. They know Texas has it, they know the Cowboys have it, so they think they’re going first class.”

Whatever its virtues for football, artificial turf distorts major league baseball. In the fourth game of this year’s World Series, a Pittsburgh line drive ricocheted off the Baltimore pitcher’s shin but rolled like a hard pool shot to Orioles first baseman Eddie Murray while the cheated Pirate sprinted futilely. Later Baltimore pitcher Tim Stoddard, at bat in the majors for the first time (because the American League’s designated hitter rule did not apply in this year’s series), tapped what should have been an easy grounder to the shortstop, but one bounce on the Tartan pad carried the ball into left field and gave that feeble stick a World Series RBI. With talent like Willie Stargell and Dave Parker, Pittsburgh hardly compromised its game to suit the Three Rivers Tartan. However, the emergence of baseball/football stadiums with artificial turf has created a playing style that was pioneered by the Kansas City Royals and adapted by last summer’s Houston Astros.

“It emphasizes speed over power,” said former Houston pitcher Larry Dierker, now an Astro publicist. “Pitchers don’t like artificial turf because of the cheap base hits. Infielders like it because they get a true bounce. Overall, baseball players don’t object because it cuts down the rain-outs, which cuts down the doubleheaders. Baseball players don’t have the injuries. They only have to worry about rug burns.”

Pro football players know that sooner or later, one way or another, they’ll get hurt. For the benefit of outsiders, they often shrug it off with an air of grim bravado. Enumerating his football surgical scars for sportswriter Frank Luksa, Charlie Waters said, “Let’s see now, there’s the left ankle, left elbow, left arm, left shoulder, and left knee. The right side of my face, right shoulder, and now the right knee . . . I’m gonna scare some rookies when they see me in the locker room.” But in more reflective moments they’re sometimes taken aback by the physical toll exacted by their livelihood. “I’ve been reading up on it,” Waters told me. “If an athlete plays three years in the NFL, do you know what his chances are of going under the knife?” His pause forced my confession of ignorance. “A hundred per cent, man. A hundred per cent.”

The noncontact threat to ankles and knees posed by too much traction against the AstroTurf grain drives the football pros close to panic and rage. They play with the knowledge that one blow against those brittle joints could end their careers—why compound the danger by tampering with the footing? Another, more constant hazard is the impact of falling on artificial turf, a significant cause of bone fractures. Though their own padding helps here, the players claim the shock-absorbency ratings of the turf pads are highly exaggerated. “The stadium crew takes good care of the rug in Texas Stadium,” Waters said, “but it’s hard. It’s like playing on a parking lot.” “Strawberries”—a euphemism for abrasions—are probably the most common artificial-turf injury. Abrasions occur on all synthetic fields, new and old, but the worst surface is worn-out AstroTurf. The weakened pile of nylon allows bare flesh to grind against the webbing—which, again, is made of material coarse enough for use in radial tires. Secondary infections often follow abrasions. When Redskins quarterback Joe Theismann was hurled against the St. Louis Cardinals’ new AstroTurf this fall, he required antibiotics throughout the next week.

Despite a guarded reference to proper footwear in the “Player Traction” chapter, “hyperflexion of the great toe” is one of only two endemic hazards actually conceded by AstroTurf in its technical reference manual. The other is excessive heat retention in summer weather. However, studies of AstroTurf by the University of Texas—which lost a player to fatal heatstroke on a grass field several years ago—indicate the widely publicized 115-degree readings on the floor fall off quickly at the physiologically more significant altitude of five feet. In any case, cooling the field simply requires spraying a little water on it. (Cowboys assistant coach Gene Stallings, then head coach for the Aggies, presided over Texas A&M’s original AstroTurf installation; he had to balance the logic of putting in a sprinkler system for that purpose against the certain scourge of jokes about those dumbass Aggies watering their artificial turf.)

SuperTurf’s technical manual just offers another sales pitch on why their product is superior to AstroTurf. The only presented evidence of the product’s greater safety is a California laboratory’s conclusion that at 72 degrees SuperTurf’s rug and pad “gives at least four times as much impact protection as Monsanto’s.” The National Football League Players Association remains skeptical. After the Consumer Product Safety Commission twice rejected the association’s pleas for regulation of the artificial-turf industry, NFLPA director Ed Garvey addressed SuperTurf’s shock absorbency claim in testimony before the U.S. Senate: “Since the federal government has failed to regulate the product, this is the only characteristic the manufacturer needs to test for safety. But is SuperTurf less hazardous? Is it safer to play on than natural grass? What are its properties in hot-humid or hot-dry conditions, or at temperatures below freezing, or when the surface has been used for two, three, or four years? What reports, what information, what technical data has the Product Safety Commission requested of the manufacturer? None that we know of.”

Despite injury considerations, on game day the players are most concerned with the field’s playability. In that sense, artificial turf serves pro football well in fair weather because it accelerates play of a game that’s already very fast. “It’s a fine surface when you’re talking about speed,” said Harvey Martin, the Cowboys defensive end. “You don’t find a dry artificial field that’s slow, but when it’s wet that’s another story. If it rains a little on grass, you can still dig in and go. If it even drizzles on artificial turf you can barely stand up. And when the moisture freezes, it’s like a hockey rink out there.”

Between pass routes, tight end Billy Joe Dupree blocks players of Martin’s size and strength. “Artificial turf makes the defensive lineman more elusive,” said Dupree. “He gains a step, maybe a step and a half, so the block’s more difficult to read. That makes me a little more alert and attentive. As a receiver, the synthetic field makes me a step faster. Footing is difficult only when the turf is wet or worn down. Then the routes have to be very defined and discreet, which takes away that advantage. But when conditions are right, it adds a couple of steps to guys like Tony Hill and Drew Pearson. It’s difficult for a defensive back to react, because he’s trying to keep up with us while running backward. Look what happened to Charlie.”

Influenced, no doubt, by the hostile crowd and the difficulty of winning up there, the Cowboys would say that their least favorite synthetic field, in terms of both injury potential and playability, is Busch Memorial Stadium in St. Louis, where Monsanto’s home office is. AstroTurf becomes more perilous through wear, which in St. Louis is accelerated by heavy use from the Cardinals baseball team. That wear not only causes more abrasions, but the pad loses its resilience and the seams split as well, increasing the danger to ankles and knees. Then there is AstroTurf’s grain, the tendency of the fibers to lean at a fifteen-degree angle. In baseball/football stadiums like Busch, AstroTurf grain runs from home plate to center field—parallel to the football sidelines. Thus the Cowboys expect alternating quarters of good traction against the grain and treacherous footing with it—a more important strategic consideration than the wind, particularly since that field is so often wet.

Equally despised by the Cowboys, though visited less often, is the Houston Astrodome. Spared the deterioration caused by ultraviolet light, indoor AstroTurf wears much longer, so the pad becomes even less resilient. Also, the Astrodome’s widely varied use means that large patches of the rug are never permanently fixed, which subjects football players to one raised 45-yard line, exposed zippers at the seams, and extremely wobbly footing on the carpeted boards laid over the ovals of baseball dirt. “You just hope the referee never puts the ball down in the bad spots,” said Oilers running back Earl Campbell, already an AstroTurf veteran—at Texas he never played and seldom worked out on grass. “AstroTurf drains your legs, especially if you practice on it.” When I asked about the New England SuperTurf, Campbell said, “That’s better, because it’s softer. In fact, that’s the best artificial field I’ve played on. Tell the Astrodome people to get that, will you?”

Receiver Ken Burrough smiled. “We’ve only played on that new Patriots field twice, and we came home happy anyway because we won big games both times. I’ve been playing in the Astrodome for ten years with the Oilers, before that at Texas Southern. That stadium goes from rodeo to baseball to football to motorcycle racing. They do the best they can. If I had my choice and the Houston weather was right, sure I’d like the natural turf. About this time of the year, when we’re beat-up and injury conscious, the grass sure feels good. On grass you can really lay out and make the catches—leave your feet completely and dive for the ball. You’ve got to be more careful on artificial turf. A few years ago in the Astrodome, just the impact of landing broke my arm when I dived at a ball. Sometimes you can protect yourself by rolling with your fall, but that depends on how you get tackled. It really does hurt, and it really gets to you. Year after year after year, you pound, pound, pound on it. You know you’re gonna get the burns, you know you’re gonna get the bruises, but there’s no easy way out in football. When we play games where the weather gets in the way, then it’s easier to appreciate that big roof. I love the Astrodome, because I love playing at home.”

Both Busch Memorial Stadium and the Astrodome now have new AstroTurf fields with a modified and reportedly much improved pad. The natural-grass alternatives are not just the gorgeous lawns of August or the safe goo of a downpour. Pro football players hated multipurpose stadiums before the invention of AstroTurf, because baseball infield paths pack so hard. Any grass football field subjected to ordinary use and unfortunate weather can quickly wear down to the dirt. For a falling body, the difference between thinly padded asphalt and alternately drenched, baked, and frozen bare earth seems fairly academic. If the NFLPA ever establishes that artificial turf is more dangerous than grass, it will probably find that the hazard is accumulative, not immediate. Players like to say that artificial turf shaves two years off the average NFL career, but they have no way to document that estimate. Still, their complaints are not just pique. When Tony Dorsett dropped a heavy mirror on his toe, Dallas team doctors held him out of the league opener because of the St. Louis AstroTurf. They let him play the next week on the hard but natural field of Candlestick Park. San Francisco removed its AstroTurf under intense pressure from Forty-niners general manager Joe Thomas. The Forty-niners felt they had to press for natural turf if they hoped to get their money’s worth from O. J. Simpson, who enjoyed his best years on Buffalo AstroTurf but now has bad knees.

The few conclusions drawn by physicians are tentative. Dr. James Garrick, director of the Center for Sports Medicine in San Francisco, studied the injuries in 228 high school games on artificial turf but could only say that wet AstroTurf is safer than dry AstroTurf—though the playability is worse—and that each product “must be evaluated individually and not lumped together as ‘synthetic’ turf.” Though Seattle orthopedist Harry Kretzler has attacked industry’s safety claims, he said, “We talk about this as if we can solve it in the laboratory by finding the right shoes and surfaces, but very few injuries occur without a collision. The way players are hit makes the difference. When a player is held up by one player and hit from the side by another in the ‘punish him’ attitude of tackling, he is going to be hurt, regardless of his shoes or the surface. . . . There isn’t enough evidence to say you should or shouldn’t use grass or artificial turf.”

Over the course of a single season, synthetic turf without question holds up better than natural grass, which makes the game more attractive to spectators. Yet on a given day its playability can be much worse. Football players love the grass in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, until the California rains begin during the climax of the football season—witness the Rams-Vikings National Football Championship play-off game two years ago. But those soaked, muddy players actually enjoyed better footing than the Oilers and Steelers, who in last year’s AFC title game played in a shallow, frigid lake on Three Rivers’ Tartan Turf. However, any spectators still around at the end were able to read the numbers on the humiliated Oilers’ jerseys.

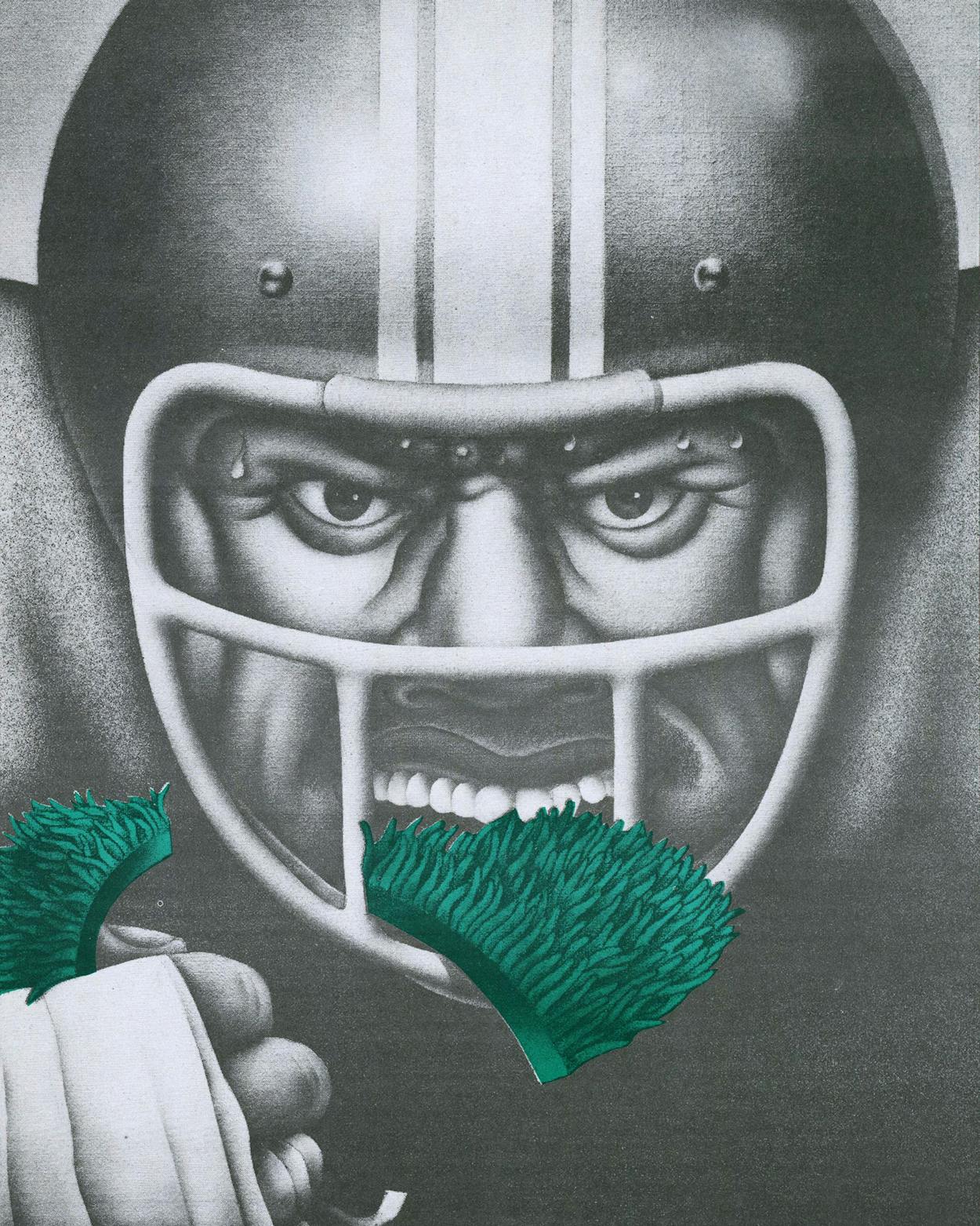

The industry’s clients seem the least concerned about the problems. AstroTurf representatives can and do cite an early National Collegiate Athletic Association study that found no substantial difference between injuries reported on synthetic turf and on grass. A Stanford Research Institute study commissioned by NFL owners concluded that artificial turf actually claimed slightly fewer serious injuries than grass, though synthetic fields reported more minor injuries. “Serious” injuries were “those causing a player to miss two or more games.” The enormous pressure (some of it self-imposed) on pro football players to compete while hurt leaves room for much punished tissue and pain inside the gray area of that definition. Yet the Monsanto sales pitch subtly derides those who complain. While illustrated with photographs of coeds gaily playing field hockey on AstroTurf, the sales material offers this slogan in response to the injury question: “Football is not a contact sport. Dancing is a contact sport. Football is a collision sport.”

Even among the athletes, there is no real consensus. The morning after last year’s Superbowl, Pittsburgh quarterback Terry Bradshaw attributed his soreness not to the fierce play but to the different strain grass places on muscles conditioned to synthetic turf. But Dallas receiver Drew Pearson—the kind of player who profits most from a dry, fast synthetic field—told me flatly, “There are no benefits to playing on artificial turf. I have nothing good to say about it. One reason last year’s Super Bowl was played so well is that it was on grass in the Orange Bowl, which has that new Prescription Athletic Turf. It was good, sure footing, yet it was very fast.

“Fans don’t think much about playing surfaces, but the athletes do. We don’t have much to say about it because we’re not on the team board of directors; we’re not even on the league injury committee. It’s very frustrating, especially when you see a player go out with a knee injury while there’s nobody even around. It makes you think about altering your own game. When you know your knee might go if you put a sharp move on a guy, maybe you should just run on through him instead of taking the chance. You know that if you’re playing on artificial turf the risk of injury is going to be greater. You have to be conscious of that every time you step on the field.”

In Texas Stadium, the column of sunlight that slants through the slotted dome would nourish grass no better than the translucent Astrodome plates. In Irving, as in Houston, a completely enclosed stadium would receive staggering air-conditioning bills. However, Cowboys general manager Tex Schramm explained the larger reason for the stadium’s design: “Mr. Murchison felt that football is an outdoor game, but the fans should be protected from the elements.” With that established, Cowboys management selected Tartan Turf because they felt it was the best buy for the money. (It was also safer than AstroTurf, according to Dr. Garrick’s study.) “We haven’t given much thought to how we’ll replace it,” Schramm said. “The problem hasn’t arisen yet.” The role of management is to make the game a marketable, profitable spectator sport. The consequences of that depend on one’s point of view. Gale Sayers, now the athletic director of Southern Illinois University, is quoted in the Monsanto sales brochure: “I’ve played on AstroTurf. Now I direct a broad-scale athletic program that depends greatly on AstroTurf. On both counts, AstroTurf rates number one with me.” When he was a Chicago Bear suffering the same painful rehabilitation from knee surgery now faced by Charlie Waters, Sayers told Sports Illustrated, “This stuff will shorten careers.”

Around the sidelines in Texas Stadium, I found the Tartan rug had bubbled in some places, torn in more. When I poked a finger into the exposed pad, I discovered it had the consistency of Silly Putty. But every Cowboys player I asked told me the home-field carpet is well kept, in excellent condition, despite the hardness. Unlike the Oilers, who switch back and forth depending upon the surface of their next game, the Cowboys practice every day on grass. Management doesn’t punish the players with artificial turf—though this year Tom Landry banned golf gloves that might have spared a few skinned knuckles because he thought they were “hot dog.” As I stood up from my pad inspection, I noticed a fleck of orange on my hand, slapped at it as if it were a roach in a kitchen. A ladybug. I noticed more orange—countless Monarch butterflies, all fluttering over the hot Tartan on a five-foot plane, where UT scientists say the air cools off. It hasn’t happened yet, but someday a wet winter storm will descend on a Cowboys game through the slot I saw filled with sunlight. While the players slip and fall on the worst conceivable footing, the fans will look downward at an ice storm. Some may then understand the temporary sense of dislocation experienced by many football players the first time they step on a synthetic field.

Many teenage males are coerced by social pressures into football pads, and many get hurt. But the ethic of “playing with pain” hasn’t really caught on with high school athletes. They pull up when tired or injured. Only the best of high school players play football on scholarship in college. In lifestyle and the choices made—not to mention the scrutiny of big-league scouts—college players are at least semipros, despite their amateur standing. Few quit football over artificial turf, but complaints filter home about the heat and the strawberries. Only the best—and, usually, the uninjured—of them play pro ball. Contrary to Vince Lombardi–type hogwash, pro football is not the natural human condition. The body is too frail to withstand that much abuse for long. Few pro football careers span more than a decade, and most players pay for those years with a lifetime of physical discomfort. Because they’re big and fast, in top condition, and psyched to all-out frenzy, they can’t possibly avoid injury; if nothing else, artificial turf increases the hazard on fair days by allowing players to run faster and collide and fall harder.

Two seasons ago, before the Cowboys traded him to the Bears, flanker Golden Richards took himself out of a game in Texas Stadium. He trotted stiffly toward the bench, leaning slightly to his left as if his ribs were injured, but his eyes were on Coach Landry. While the pros are the ultimate athletically, they’re also the end of the line. The injured player isn’t granted convalescent leave; he loses his job. Richards held his composure until he was out of the coaches’ line of sight, then his right hand shot to the abrasion on his elbow, and he whirled into a wild gyration of pain. He couldn’t have writhed, stomped, and cursed more if someone had just doused an open wound with kerosene.

That wasn’t even a “reportable” abrasion. In order to make the league injury stats, a synthetic-turf abrasion must sideline a player for two practice sessions. Richards went back in the next time the Cowboys had the ball. Management doesn’t really want to hear about player injuries; we, the spectators, don’t really want to see them. The game is fun to watch—as long as it’s moving. In the stands, we’re too far away to see much anyway. At home, the network cuts away for a commercial. When Charlie Waters went down, the zoom lens didn’t focus on him long.

What the Pros Really Think

“Artificial turf hurts, and it really gets to you. Year after year, you pound, pound, pound on it. You’re gonna get the burns, you’re gonna get the bruises, but there’s no easy way out in football.”

—Ken Burrough, wide receiver, Houston Oilers

“It drains your legs, especially if you practice on it. New England’s Super Turf is better, because it’s softer. In fact, that’s the best artificial field I’ve played on. Tell the Astrodome people to get that, will you?”

—Earl Campbell, running back, Houston Oilers

“Artificial turf makes the defensive lineman more elusive. He gains a step, maybe a step and a half. The synthetic field makes me, as a receiver, a step faster. Footing is difficult only when the turf is wet or worn down.”

—Billy Joe Dupree, tight end, Dallas Cowboys

“There are no benefits to playing on artificial turf. I have nothing good to say about it. You know that if you’re playing on artificial turf the risk of injury is going to be greater. You have to be conscious of that every time you step on the field.”

—Drew Pearson, wide receiver, Dallas Cowboys