Barry Corbin got a funny look in his eye. “All the world’s a stage,” he intoned, leaning forward and peering at me, “and all the men and women merely players.” His deep, familiar drawl followed the cadence of Shakespeare’s words. “They have their exits and their entrances, / And each man in his time plays many parts, / His acts being seven ages.”

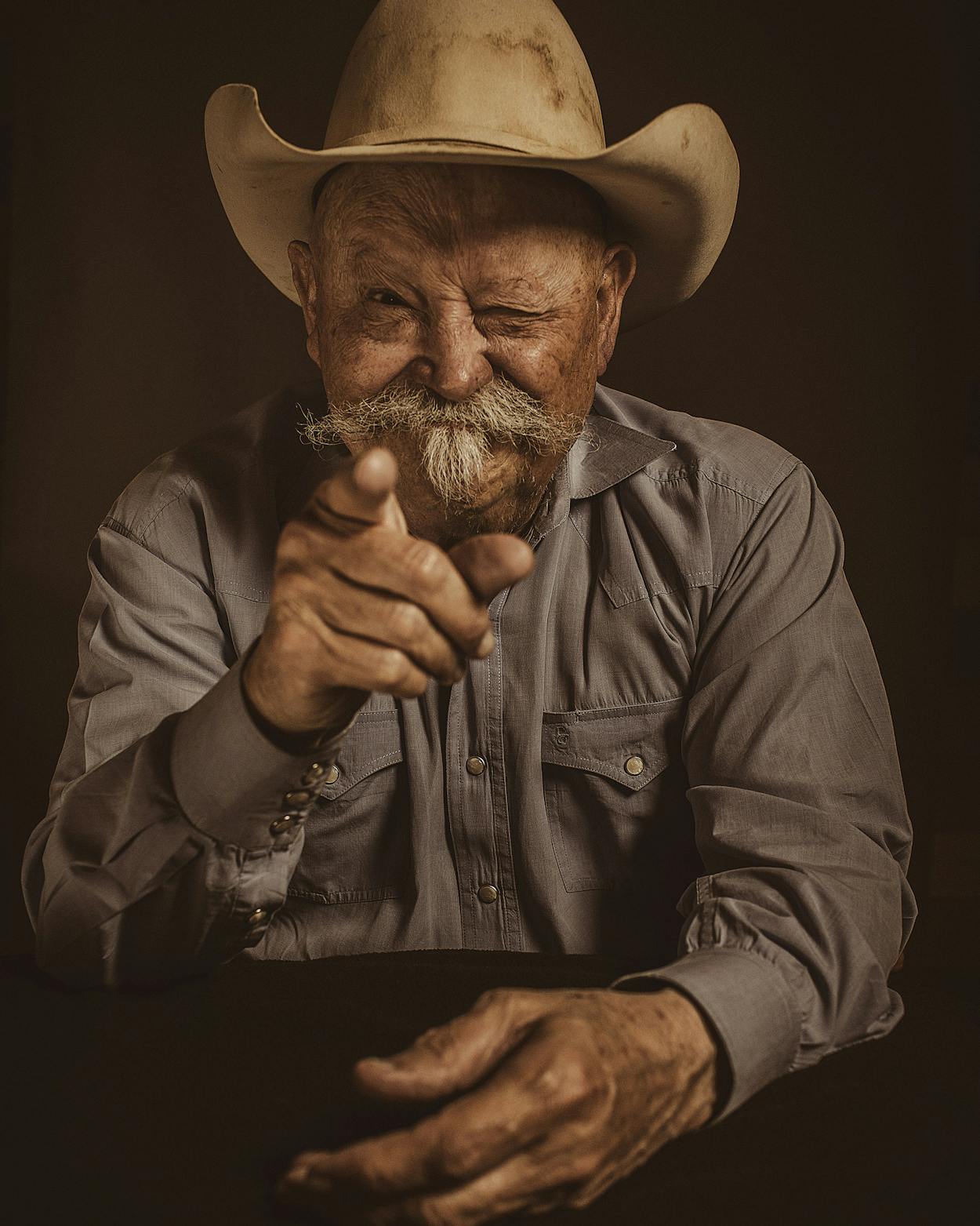

The actor—who played shady Sheriff Fenton Washburn in Dallas, genial Uncle Bob in Urban Cowboy, and dim-witted Roscoe Brown in Lonesome Dove—paused for effect, sitting in his Fort Worth home. Corbin has no hair on the top of his head, and alopecia has just about claimed his eyebrows, but a prodigious gray goatee encircles his mouth. He has an impish air, even when interpreting the Bard. “At first, the infant, / Mewling and puking”—he spit out the word—“in his nurse’s arms. / Then the schoolboy with his satchel / And shining morning face, creeping like snail / Unwillingly to school.” The leather sofa beneath him creaked. “And then the lover, / Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad / Writ to his mistress’s eyebrow.”

We had been talking about some of the hundreds of roles Corbin has played in his career, from old cranks and lawmen to Falstaff and Macbeth. He said that he’d always loved Shakespeare, which led to this impromptu performance of Jaques’s melancholy Seven Ages of Man soliloquy from As You Like It.

He cruised through the stages—youth, middle age, retired old fart—swatting his thigh, raising and lowering his voice to emphasize notes of vigor and lassitude, ambition and loss. As he neared the end, he slowed his speech and looked down at his hands. “Last age of all, / That ends this strange, eventful history, / Is second childishness and mere oblivion, / Sans teeth, sans taste, sans eyes, sans”—he took one long, final pause—“everything.”

I was the lone member of Corbin’s audience, but I applauded, and his face broke into the broad smile I knew from so many of his roles. For a moment, I pictured Uncle Bob in his hard hat, beaming at John Travolta and stuffing some chaw into his mouth after reciting another famous monologue, this one about swallowing (or, as Corbin pronounced it, “swallerin’ ”) one’s pride. Right before Uncle Bob was tragically struck by lightning.

I asked Corbin if that was his favorite bit of Shakespeare. Not really, he said. “But it’s one that means something to me the older I get. It means more and more to me because I’ve been through all the stages. I’m in the last stage, without any teeth.”

Corbin turned eighty in October, and up until the pandemic, he was still working, appearing in the Fox drama 9-1-1: Lone Star and playing a stubborn old man who refuses to leave his home on Better Call Saul. Corbin has always kept busy. Over his sixty-year career, he’s had more than two hundred roles onstage, on TV, and in the movies. They’ve mostly been supporting roles, often authority figures—a natural fit, given his large frame and confident presence. He’s played fifteen sheriffs, several generals, a few wise uncles, a swaggering astronaut, and a hard-core basketball coach. He’s also played psychotic patriarchs, wealthy Texans, Santa Claus, and Lyndon Johnson. Even when his characters are overbearing or murderous, Corbin finds ways to make them human and likable—so much so that he often steals the show, as he did portraying General Jack Beringer in WarGames and astronaut Maurice Minnifield in Northern Exposure. Known as a character actor, he always seems like he’s genuinely enduring whatever his character is enduring—while also somehow remaining Barry Corbin.

The way he talks has a lot to do with this. Corbin speaks in a comfortable lilt, an accent that rolls out of his mouth, more drawl than twang. It’s flat but musical, slightly nasal with a bit of a rasp. When he speaks deliberately, which he often does, his voice is deep and resonant. He sounds like he knows what he’s talking about, like he can be trusted, like he means what he says.

It’s a voice that has narrated documentaries on everything from the space program and Old West gunfighters to the history of Harley-Davidson motorcycles; that has read audiobooks of American lore like Old Yeller and the 1930s Max Brand pulp cowboy tales; that for more than twenty years was the voice of promo reads for Fort Worth country station 99.5 the Wolf, delivering lines like “I’d rather be a fence post in Texas than a king in Tennessee.”

You’ll hear a lot of accents like Corbin’s if you go to the Llano Estacado, also known as the Southern Plains, an area that in Texas runs east of New Mexico, south of the Canadian River in the Panhandle, north of the Hill Country, and west of Wichita Falls. If there’s a capital of this region, it’s Lubbock, also known as Hub City. The Llano Estacado is flat, tough country: scrub, stones, and sand. Corbin likes to say of the Southern Plains accent, “It’s flat, like the land—it’s really part of the land. I tell people it has to do with ingesting a lot of sand growing up.”

Leonard Barrie Corbin was born October 16, 1940, in the ranching and cotton town of Lamesa, sixty miles south of Lubbock, and grew up mewling into the wind that roared down the plains from Canada. His paternal grandfather had moved to Lamesa from Lampasas in the twenties because he wanted to raise cotton and the land there looked good. “It was beautiful green country,” Corbin said, recalling the family’s pre–Dust Bowl creation myth. “Like the Garden of Eden.”

The boy’s parents, Kilmer and Alma Corbin, were schoolteachers who married young. Kilmer had been stricken by polio as a child, which limited the use of his right hand and left him unable to do farmwork. He developed into a bookish kid. In photos from his youth, everyone else wears suspenders while Kilmer sports a dress shirt and tie. Alma (who had been born in a covered wagon on the trip to Lamesa) named their first son after J. M. Barrie, the author of Peter Pan. When Barrie reached school age, he became “Barry” to differentiate himself from a female classmate who had the same name. Though his parents weren’t horse people, Barry spent summers at his grandfather’s, who put him in the saddle every day. He loved the feeling. “A horse wants to do whatever you want him to do,” Corbin told me. “If you want to compare it to being one entity, you’re the brain, and the horse is the body. So you’ve got to be in sync with the horse. Got to make him think whatever you’re gonna do is coordinated. And make him think it’s his idea. Then you get along.”

The Corbin family—brother Blaine and sister Jane followed Barry—lived just north of Lamesa on Highway 87, in a house across the road from a cotton gin and down the street from the school where Kilmer and Alma taught. Kilmer, an FDR Democrat, was an ambitious young man who at 22 decided to run for county judge and won. When he set his sights on the state Senate in 1948, his firstborn helped nail up posters and hand out cards on the courthouse square. Kilmer won, becoming the youngest senator in the Legislature. After he served two terms, the family settled in Lubbock, where Kilmer, who lacked a law degree but had passed the State Bar exam, opened a legal practice. He would take Barry with him on Saturdays when he visited clients to collect payment. Sometimes folks would try to negotiate, pulling out a bottle of whiskey or offering up a chicken or goat.

Corbin remembers the banter from those long-gone interactions. He says the way folks talk in the Southern Plains is something they carry proudly throughout their lives. But it’s not just how they talk; it’s what they say. “A big part of our identity is telling stories,” he told me. The expanse of the land required people there to learn to fend for themselves—and to entertain themselves. “Most of us became storytellers out of boredom.” Many others from the Southern Plains—Terry Allen, Joe Ely, Buddy Holly, Waylon Jennings—became musicians for similar reasons: there was nothing else to do. “There’s an attitude from people who come from this part of the state,” says Lubbock-born songwriter and poet Andy Wilkinson. “You see it in musicians and artists, something here that causes people to have a combination of a perfect sense of self-confidence and a perfect sense of humility. That carries over into the way a person presents himself. A lot of that is his voice.”

Like most folks in the area, Corbin says “ho-tel,” “tor-nay-duh,” “cain’t.” He drops the letter g at the end of words. You can hear this to great effect when you listen to his narration of Buffalo Altar: A Texas Symphony, a 1998 piece of music and writing by J. Todd Frazier and Stephen Harrigan. It’s a love letter to old Texas, an 81-year-old oilman’s reminiscence of wild days gone by, including the time, fifty years earlier, when he and an elderly rancher entered a cave and watched the sun rise over an altar of ancient buffalo jawbones. In each public performance, Corbin, wearing a white Stetson, would stand onstage and read the story, weaving in and out with the music. “Texas is what connects me and that prehistoric fella and that old rancher and that dead buffalo,” he’d say, interlocking his fingers. “It’s not just the place we live in; it’s the place that lives in us, even after we’re dead and lookin’ toward the sun with empty eyes.”

Harrigan was moved every time he heard Corbin recite the story. “There’s a coauthorship level when a great actor is reading your work,” Harrigan told me. “It’s a mysterious process. Barry enhances every word. He adds something that wasn’t there before.”

Corbin told me that in his long career, he’s occasionally had trouble with directors over his voice, but it’s happened only in New York and only in the theater. “You don’t talk that way onstage,” they would tell him. Corbin would shake his head in reply: “No, this is me. That’s what I talk like. And if that bothers you, then you’ve got to find somebody else.”

From an early age, Corbin remembers, he’s been observing the people around him: listening to them talk, discerning their differences, taking mental notes. In high school, when he wasn’t buying horses to retrain and sell at a profit, he was people-watching at the Purple Onion, a gathering place for local beatniks near Texas Tech University. “You’d go in—there’d be a fellow, older, about thirty, he’d grown a beard and wore a beret, walked around with a walking stick,” Corbin said. “There’d be people doing bad Allen Ginsberg–like poetry, snapping their fingers. You’d order a cup of espresso, they’d put five teaspoons of instant coffee in a cup and pour boiling water over it, put a peppermint stick in there, and charge you seventy-five cents.”

By the time Corbin got to Tech, in 1959, he looked like a young, roguish English actor: six feet tall, 160 pounds, black hair, and dark brown eyes. He had acted throughout high school and was determined to continue in college. His freshman year, he wore a fat suit to play Falstaff in The Merry Wives of Windsor. He took Shakespeare seriously and devoured the playwright’s complete works. “I wanted to see what was there,” Corbin told me. “A play like Hamlet, there’s so much there that you miss it the first time. A play like Macbeth, it’s almost a modern play, a shortish play. And some of them are just not worth reading, hardly, like As You Like It.”

Corbin wasn’t a great student, but he was already developing into a fine actor, playing parts in modern dramas like A View From the Bridge. He was a gregarious free spirit, and if he didn’t like the plays the theater department had scheduled for an upcoming semester, he would drop out and work on an oil rig, soaking up another world’s characters and their stories.

Corbin didn’t graduate, and in 1961 he joined the Marines, spending two years at Camp Pendleton, in Southern California. When he returned to Lubbock, he jumped back into acting. Jamie Howell, an actor who shared the stage with Corbin at Tech, said Corbin was already on a different level from other community theater performers. “It was like watching a major leaguer play with some double-A players,” Howell told me. “He had this transportive ability. He could take an audience to a place where he was taking himself. He’d touch your soul in some way, and I’m talking about touching the soul of West Texans, who are not easy to touch.”

In 1965 Corbin married his girlfriend, Marie Elyse Soape, who was also an actor. Lubbock didn’t offer many opportunities for the couple to pursue their stage ambitions, so they headed east. They spent a year in Chicago, where Corbin worked at a bookstore and did a community theater production of Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker. They spent time in Raleigh, where Corbin taught acting at North Carolina State University, and he performed in Ghosts, by Henrik Ibsen. He also played Mercutio in Romeo and Juliet at the famed Barter Theatre, in Abingdon, Virginia.

The older Corbin got, the more fascinated he grew with his craft: creating flesh-and-blood characters from written dialogue. With each new town and each new production, he learned new ways of deploying his voice, face, and body to transport himself and the people who watched him.

HE’D TOUCH YOUR SOUL IN SOME WAY, AND I’M TALKING ABOUT TOUCHING THE SOUL OF WEST TEXANS, WHO ARE NOT EASY TO TOUCH.

Corbin moved to New York in 1967, with Soape eventually joining him, and the couple settled in Greenwich Village. He decorated their kitchen with photos of horses, cowboys, and buffalo. He hung a Texas flag on the wall. Although he acted on Broadway, Corbin also used the city as a base to venture elsewhere, to the American Shakespeare Festival, in Stratford, Connecticut, and to several dinner theaters in the Northeast.

In 1970, Corbin and Soape had a son, Bernard, though not long after, the couple divorced. Corbin held on to the apartment but hit the road for more stage work: Alabama, Mississippi, Massachusetts. Some nights he slept in his car, but he enjoyed the itinerant life—doing roles he knew, subbing for other actors, stumbling upon new opportunities. In 1976, while driving back to New York, he stopped in Atlanta to visit a friend and heard about an audition for a local TV shoot. Corbin ended up getting the part, playing the world’s greatest hot-air balloon pilot in Movin’ On. And he did some other TV: a guest spot in an episode of Hawaii Five-O, a hit man in The Andros Targets. That year, he married Susan Berger, a fellow actor he had met in Alabama. The two moved into Corbin’s apartment, and he went back to touring. Life was good: he got to do what he loved, and he was successful at it.

Then, in July of 1977, New York was hit by a blackout. The city was already in financial chaos, plus the Son of Sam was on the loose. After hunkering down through a hectic night of looting, miserable heat, and food spoiling in the refrigerator, Corbin decided he had had enough. He was approaching forty and wanted to see if he could make a childhood dream come true. He and Berger drove to Los Angeles.

While Corbin was learning to act, he was also learning to write, scripting plays and filling them with characters he knew from home. His first finished piece was Suckerrod Smith and the Cisco Kid, in which a young man from Queens heads to Hollywood to become a movie cowboy and stops along the way at a bar in West Texas. There he meets, among others, free-spirited Suckerrod Smith (the name comes from an oil well part), who was based on Corbin’s grandfather. The play had runs in Alabama and Southern California. While serving as a playwright in residence at the University of South Alabama in 1974, Corbin wrote that these characters had lived in his head since he left home nine years earlier: “Some of them are dead, some are alive, but they’re all full of life, breath, blood, and bone to me.”

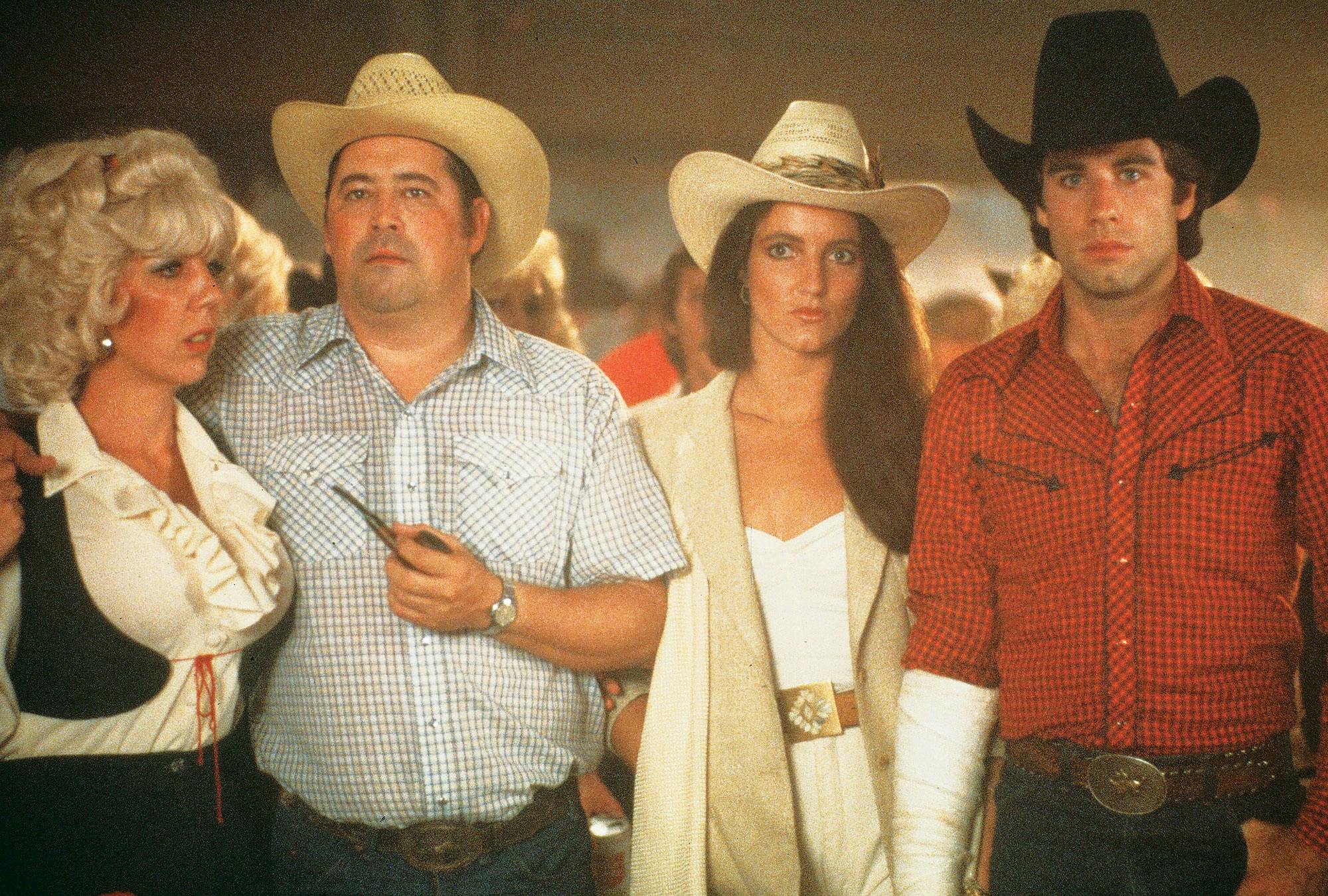

When Corbin arrived in L.A., he penned a longer play called The Whiz Bang Cafe, which involved a collection of personalities at a truck stop in Throckmorton, Texas, about halfway between Lubbock and Fort Worth. Corbin was part of a troupe performing the play, and he invited an agent to see it. She liked his writing but loved his acting, and she got him an audition, which led to his first big-screen role: Uncle Bob in Urban Cowboy.

Corbin, the 39-year-old film rookie, looked completely at ease with star John Travolta, smiling, smoking a pipe, dispensing country wisdom. One of the emotional peaks of the film comes toward the end, when Bob is killed by lightning, but immediately before that, he gives his nephew Bud (Travolta) some avuncular advice on dealing with his estranged wife. The director thought the lines as written were too bare, so the day before shooting, he asked Corbin to punch them up. Corbin thought back to his childhood and the cantaloupes his grandmother had grown next to her garage, and then he let his imagination go. In the scene, Bob told Bud exactly why he had swallowed his pride numerous times: “Without Corene and them kids, hell, I’d be just another old pile of dog shit in the cantaloupe patch, just drawing flies.” Travolta, who didn’t know the line was coming, let out a delighted snicker—as did audiences nationwide who came in droves to see the movie.

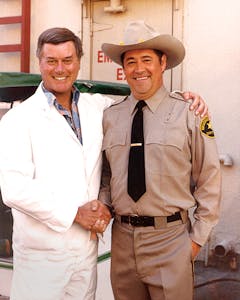

Throughout the early eighties, Corbin laid the groundwork for decades of future TV law enforcement roles with his performance as Sheriff Fenton Washburn in Dallas, a crooked but engaging lawman. He also had supporting turns in two box-office hits—as a prison warden in the Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor comedy Stir Crazy and as a wealthy Texas gambler in Clint Eastwood’s Any Which Way You Can.

Nothing, however, could have prepared him for the success of WarGames, in 1983. Corbin played Jack Beringer, a four-star general who has to prevent a computer-driven World War III started unknowingly by a teenage hacker, played by Matthew Broderick. Once again, a director asked Corbin to get inside his character’s head and add some dialogue. John Badham told the actor that Beringer needed to utter a line showing how desperate the situation was and suggesting that, since none of the adults could head off nuclear annihilation, they turn to the teen. Corbin assured Badham he’d figure something out, and he remembered a day back in Lamesa when he had dared his cousin to urinate into the engine of a tractor their grandfather had left running in a field. The next day, at the appointed time, Corbin cried, “Goddamn it! I’d piss on a spark plug if I thought it’d do any good! Let the boy in there, Major.”

By then, Corbin and Berger had two sons, James and Chris, and Corbin had built a reputation for versatility and a sense of humor. He got to use both in 1990, when, at age fifty, he landed the TV role that, for many, defines him: the arrogant ex-astronaut Maurice Minnifield, who runs the town of Cicely, Alaska. Northern Exposure was witty and weird, and Corbin helped set the tone, playing a macho man who loved show tunes, a braggart who cried, a hothead with a big smile. One of Corbin’s close friends on set was John Cullum, also a veteran stage actor, who played tavern owner Holling Vincoeur. At the end of the very first episode, the two men—each vying for the same woman’s affection—come together to settle their beef. Corbin’s character (the loser) tells Cullum’s about his experience floating in space. “Is that what it’s like, Holling?” Corbin asks, as his face collapses into tears. “Being in love?”

Cullum told me that he and others on the set were often in awe of Corbin: “Barry is such a good actor that sometimes he doesn’t realize he’s acting. That’s the most perfect acting you can do. It’s so natural that it’s really him. He was totally authentic, almost a method actor. He deliberately created this character of Maurice.”

Corbin was happy playing minor and ensemble parts—the roles kept him working, and they were often more interesting than playing the lead. “Being a movie star,” he would say, “is the biggest pain in the world.”

Of all his roles, Corbin’s favorites have been in old-fashioned westerns, the ones with cowboys, horses, and triumphant good guys. “The western is our mythology,” he told me. “Usually in a western, the hero is a guy who, well, what John Wayne said: ‘Courage is being scared to death and saddling up anyway.’ And that’s pretty much what a western ought to be.”

He learned to love them as a boy, spending Saturday afternoons in Lamesa’s Majestic Theater. “We’d be hollering and carrying on,” Corbin recalled. “There’d be a few of the local cowboys from the ranches who came in on horseback. They’d just hobble their horses out on the courthouse square and let them graze on the grass and go in and watch the picture show.” Corbin and his friends would bring cap pistols to express their disapproval during musical numbers. “Whenever they’d start singing, we’d start popping off them caps,” he said. “We didn’t care for them to sing.”

He adored the heroes—Gary Cooper, John Wayne—but was intrigued by horsemen like Ben Johnson and bit players like George “Gabby” Hayes and the comic actor Al St. John, who performed in westerns under the name Fuzzy Q. Jones. “I could do that,” Corbin thought. When he and his friends got home, they would divvy up parts from the movie and act it out all over again. He decided to be an actor when he grew up, but not a leading man. He wanted to be a character.

In some of his favorite screen roles, he’d ride horses, often imagining he was playing his grandfather. “Once I get on a horse, I feel like I’m whole,” he told me. “I’m walking around afoot, I feel like I’m missing something.” One of those performances was in Lonesome Dove. Corbin had read the novel and told his agent he’d take any part in the 1989 adaptation. Another was in Conagher, made a couple of years later, in which Corbin played a good-hearted stagecoach driver who helps the hero (Sam Elliott) get the girl. For the movie, Corbin had to learn to drive a team of six horses, something he hadn’t done before, but he was such a natural that he learned in two days.

Corbin loved the horse operas, but his turns in Dallas and Urban Cowboy solidified his standing in modern westerns. Perhaps his most memorable character was Uncle Ellis, in 2007’s No Country for Old Men. Corbin plays a former Texas lawman who has been paralyzed from the waist down by a bullet, and he shares his scene with Tommy Lee Jones, who portrays his nephew, a sheriff who has spent the previous 110 minutes failing to catch the most diabolical villain since Henry Fonda in Once Upon a Time in the West.

To play Ellis, Corbin drew on memories of seeing old men in wheelchairs during his youth in Lamesa and Lubbock. “Back then,” he told me, “we thought they were used up. When I did the scene, I was thinking about what they felt like inside, which is what they were when they were thirty. But nobody sees that.”

The scene is only five minutes long, yet it somehow encapsulates the relentless evil in the movie—and the world. Corbin, then 66, did what he’s done since he was young: he spun a story. Bearded and confined to a wheelchair in a squalid desert shack, Ellis tells his nephew how one of their kin was killed seventy years before by Indians. It’s a remarkable monologue of violence, death, and, finally, burial “in that hard, old caliche,” told in Corbin’s slow Southern Plains drawl. When he’s done, Ellis tries to comfort his nephew, who is quitting the sheriff’s department, feeling overmatched. “What you got ain’t nothin’ new,” Corbin says, staring at Jones under a heavy brow, his face lined with shadows and age. “This country is hard on people. You can’t stop what’s comin’. Ain’t all waitin’ on you. That’s vanity.”

The message—that there’s only so much a good person can do about evil—runs contrary to the themes of almost every traditional western ever made, where heroes triumph and justice is done. The look on Corbin’s face, as well as his delivery, makes it seem as if King Lear himself has been dressed in grubby overalls and dropped into the West Texas desert. The look on Jones’s face says he believes every word.

In 1991, after filming the first season of Northern Exposure, Corbin got a phone call from his agent that would change his life: a young woman named Shannon Ross was claiming to be his daughter. Corbin called Ross and, within minutes, realized she was indeed his child. Her mother and Corbin had had a fling in 1964, but the mother had never told him about their daughter. Ross, who lived in Arlington, Texas, had sought him out because one of her two kids had cerebral palsy, and she wanted to know if her birth father had similar issues.

Soon, Corbin and Ross were talking every day, and he would often fly her and her family out to Seattle, where he was living at the time. Corbin kept a couple of horses and was delighted to find that Ross also rode. He would break out his trick rope and perform for the kids. Corbin had recently taken to riding cutting horses and entering competitions and celebrity rodeos. “It’s like riding a bucking horse, except he goes backward and sideways,” he said. “They’re the best all-around equine athletes that there are. All a racehorse knows how to do is turn left. A cutting horse has to mirror the moves of a cow. And the closer you can get mirroring those moves, the higher your score is going to be. And the only cues you have are leg pressure and spur.”

When Corbin’s work in Northern Exposure earned him an Emmy nomination in 1993, he and Ross rode horses to the ceremony. That year, Corbin’s second marriage ended. Two years later, Northern Exposure shot its final episode, and Corbin found himself drifting—visiting his sons in California, sleeping on Ross’s couch. He was ready to move back to Texas, and Ross, also recently divorced, was ready to move in with him. Corbin bought a fifteen-acre ranch in east Fort Worth that had once belonged to former Texas Rangers manager Bobby Valentine. He brought his horses from Seattle and bought six head of cattle and a bull. Now that the series was over, he returned to westerns, doing The Journeyman with Willie Nelson and Crossfire Trail—a film that for a few years was the most popular made-for-TV movie ever.

A LOT OF PEOPLE WORK TOO HARD AT ACTING. IT’S ALL ABOUT HUMAN BEHAVIOR. I NEVER TIRE OF PEOPLE-WATCHING. YOU LEARN THINGS EVERY DAY FROM LIVING.

By then, Corbin was in his sixth age, with spectacles on his nose, and he began looking for projects that could connect him with his roots. He had grown up hearing stories about Charles Goodnight, the legendary cowboy and cattle baron who had established the JA Ranch at Palo Duro Canyon, south of Amarillo. Corbin latched onto the idea of doing a one-act play. “I thought, ‘We need to pay our respects to this guy—he’s the reason in large part that Texas is what it is today,’ ” Corbin told me. “Goodnight was a Renaissance man with no real education who learned from observing. He was a businessman, but he was a dreamer more than anything else.” Corbin knew Goodnight’s world, the way people talked and acted, and wanted to set the play on the last night of his life, looking back over the previous 93 years. In 1996 Corbin sought out poet Andy Wilkinson, who had composed an album of songs and verse about Goodnight, to collaborate.

When Charles Goodnight’s Last Night opened, Corbin did his own makeup for the show, and his white hair and goatee so resembled the titular character’s that Wilkinson’s grandmother—who had known the cowman in her childhood—saw Corbin onstage and said, “My goodness, that’s Uncle Charley!” Corbin completely inhabited Goodnight, Wilkinson said. “With Barry, you recognize that there’s a human being giving you the role.”

A skull hangs over the door to Corbin’s back office, one that belonged to a bull named Will. The bull had been a gift from the Will Rogers Memorial Museum, in Claremore, Oklahoma, which gave it to Corbin in 1995. Corbin kept Will with his cattle and two horses on the ranch when he first moved back to Texas. But after the drought of 2003, he gave away the cows and passed Will along to a rancher friend who had a large herd and room for Will to roam. One day in 2010, Will wandered off. Nobody saw him again; a year later, some cowboys found his skeleton. “He was sort of a good friend of mine,” Corbin told me, nodding at the skull.

Corbin has no livestock anymore. One of his horses died ten years ago, and he gave the other to a children’s riding program. In 2012 Corbin and Ross moved from the ranch to a compound of several homes in Handley, not far from the grave of Lee Harvey Oswald. It’s more urban there, no place for animals. Corbin married Jo, his third wife, in 2015, and since then they’ve lived across the street from Ross and her second husband.

One wall of the office is a bow to Corbin’s past, adorned with awards, plaques, and honors from various Texas halls of fame and the Screen Actors Guild. There are a dozen bronze statues: cowboys on horseback, cowboys roping calves, cowboys standing alone. The sculptures commemorate a bygone way of life, one Corbin saw vestiges of as a child and then wound up playing onscreen. He told me his favorite award came from the Hall of Great Western Performers at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, in Oklahoma City—basically the Smithsonian for cowboys. “Tom Mix was the first one inducted,” Corbin said, looking at a statue of a cowboy turned to the side on horseback with one hand holding the reins and the other dangling beside him. “And then Gary Cooper. John Wayne was in there somewhere.” Corbin was inducted in 2018, a year after Alan Ladd and a year before Kevin Costner. I told him I thought the cowboy was gazing reflectively into the distance. Corbin reckoned that, more likely, he was counting cattle.

Hollywood doesn’t make many westerns these days. That bothers Corbin, who’s spent much of the past decade shooting TV shows like Anger Management, The Ranch, and Modern Family. “There are no movie horses,” he told me. “No wagons left, no stagecoaches. The stuntmen think a horse is like a motorcycle. I’m looking for a reason to get on horseback while I can still do it. It’s not gonna be long before I can’t get up there.” He said he’d like to do one more western. He smiled when I reminded him of a line from Buffalo Altar: “Sitting on his horse, that old man looked about twenty years younger.”

I asked him about the last time he rode competitively, and he leaned back and showed me a bright gold belt buckle. “2000 Celebrity Champion,” it read. The buckle came from the National Cutting Horse Association’s annual cancer care services event in Fort Worth. “That’s the last buckle I won,” Corbin said. “The last time I got on a cutting horse was before we shut down for this virus.” How did it feel? “Good. As soon as I got on the horse and started loping around a little bit, I was right back where I used to be. I’m not gonna win anything right now, but, you know, I’m not as much of a daredevil as I used to be either.”

Corbin wants the pandemic to end as soon as possible. He dreams of going back to work and keeps a bag packed in his closet, as he has for most of his professional life. “Usually my jobs come up at the last minute. They call on Tuesday and say I have to be in New Zealand on Thursday.” Until the calls start coming again, he bides his time watching old movies, taking walks through his neighborhood, and keeping up with the world. “I spend a lot of time out here,” he said, “reading the paper, looking at TV, cutting out some of these articles, trying to educate somebody—which, nobody would ever read ’em.”

Perhaps Corbin became a great American character actor because he’s a natural who’s spent a lifetime honing his talent, but to hear him tell it, he’s learned the most from keeping his eyes open. “It informs who I am,” he told me. “A lot of people work too hard at acting. It’s all about human behavior. I never tire of people-watching. You learn things every day from living.”

He maintains a sanguine view of the world and his place in it, posting photos on Facebook of him and Jo and his kids, as well as videos of himself reading children’s books and talking to fans. In the spring, after one of them informed him that 99.5 the Wolf had, for some reason, decided to end its association with him (the fan had called the station, which never actually contacted Corbin), the actor posted a video message to the Wolf. Instead of airing a grievance, Corbin smiled into the camera. “Good luck,” he said in his familiar lilt. “I want to thank you sincerely for a great twenty years, and I’ve enjoyed every minute of it.”

As with anything Barry Corbin says, it sounded like he meant every word.

This article originally appeared in the January 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Seven Ages of Barry Corbin.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Television

- Longreads

- Film