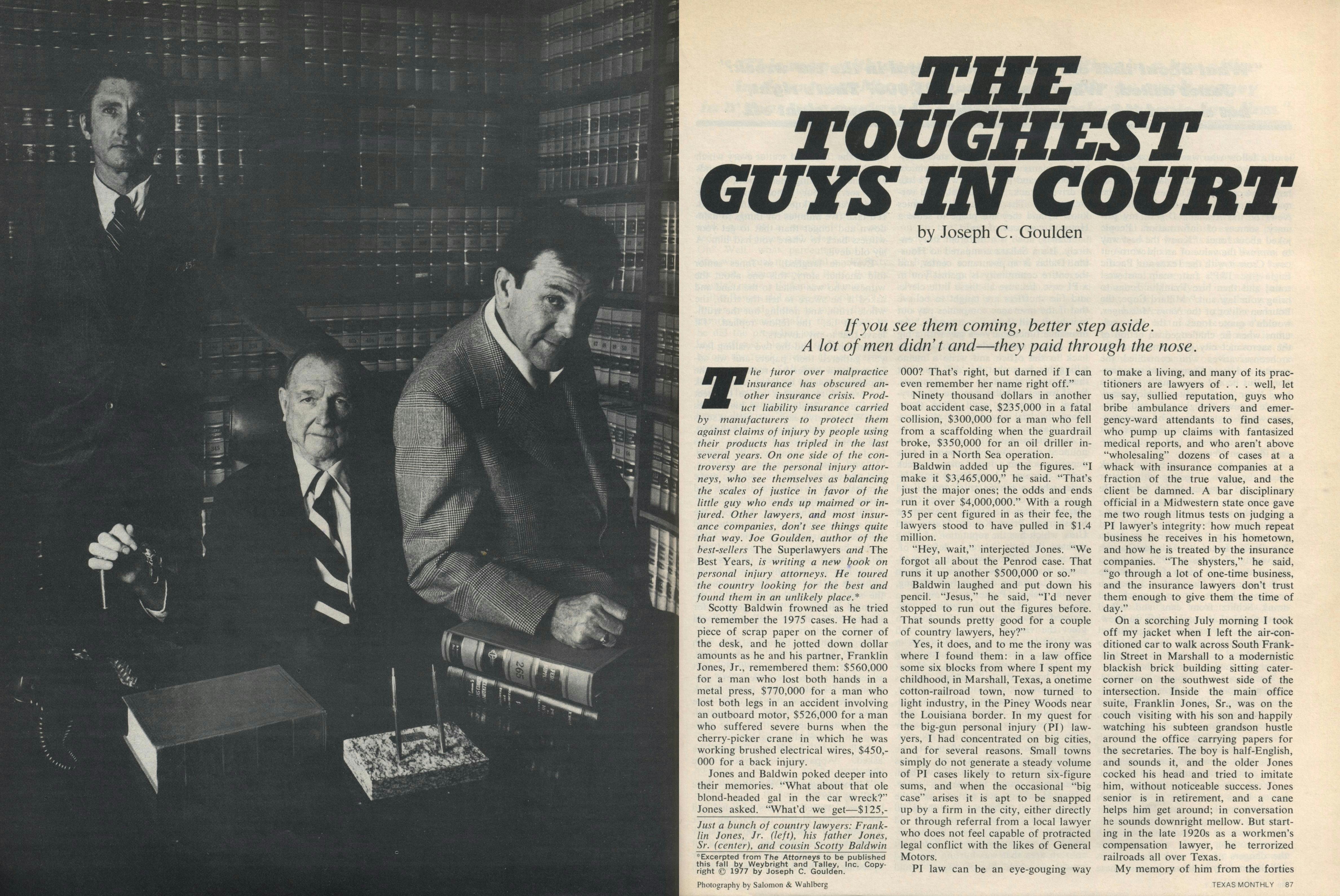

The furor over malpractice insurance has obscured another insurance crisis. Product liability insurance carried by manufacturers to protect them against claims of injury by people using their products has tripled in the last several years. On one side of the controversy are the personal injury attorneys, who see themselves as balancing the scales of justice in favor of the little guy who ends up maimed or injured. Other lawyers, and most insurance companies, don’t see things quite that way. Joe Goulden, author of the bestsellers The Superlawyers and The Best Years, is writing a new book on personal injury attorneys. He toured the country looking for the best and found them in an unlikely place. (Excerpted from The Attorneys by Joseph C. Goulden.)

Scotty Baldwin frowned as he tried to remember the 1975 cases. He had a piece of scrap paper on the corner of the desk, and he jotted down dollar amounts as he and his partner, Franklin Jones, Jr., remembered them: $560,000 for a man who lost both hands in a metal press, $770,000 for a man who lost both legs in an accident involving an outboard motor, $526,000 for a man who suffered severe burns when the cherry-picker crane in which he was working brushed electrical wires, $450,000 for a back injury.

Jones and Baldwin poked deeper into their memories. “What about that ole blond-headed gal in the car wreck?” Jones asked. “What’d we get—$125,000? That’s right, but darned if I can even remember her name right off.”

Ninety thousand dollars in another boat accident case, $235,000 in a fatal collision, $300,000 for a man who fell from a scaffolding when the guardrail broke, $350,000 for an oil driller injured in a North Sea operation.

Baldwin added up the figures. “I make it $3,465,000,” he said. “That’s just the major ones; the odds and ends run it over $4,000,000.” With a rough 35 per cent figured in as their fee, the lawyers stood to have pulled in $1.4 million.

“Hey, wait,” interjected Jones. “We forgot all about the Penrods case. That runs it up another $500,000 or so.”

Baldwin laughed and put down his pencil. “Jesus,” he said, “I’d never stopped to run out the figures before. That sounds pretty good for a couple of country lawyers, hey?”

Yes, it does, and to me the irony was where I found them: in a law office some six blocks from where I spent my childhood, in Marshall, Texas, a onetime cotton-railroad town, now turned to light industry, in the Piney Woods near the Louisiana border. In my quest for the big-gun personal injury (PI) lawyers, I had concentrated on big cities, and for several reasons. Small towns simply do not generate a steady volume of PI cases likely to return six-figure sums, and when the occasional “big case” arises it is apt to be snapped up by a firm in the city, either directly or through referral from a local lawyer who does not feel capable of protracted legal conflict with the likes of General Motors.

PI law can be an eye-gouging way to make a living, and many of its practitioners are lawyers of . . . well, let us say, sullied reputation, guys who bribe ambulance drivers and emergency-ward attendants to find cases, who pump up claims with fantasized medical reports, and who aren’t above “wholesaling” dozens of cases at a whack with insurance companies at a fraction of the true value, and the client be damned. A bar disciplinary official in a Midwestern state once gave me two rough litmus tests on judging a PI lawyer’s integrity: how much repeat business he receives in his hometown, and how he is treated by the insurance companies. “The shysters,” he said, “go through a lot of one-time business, and the insurance lawyers don’t trust them enough to give them the time of day.”

On a scorching July morning I took off my jacket when I left the air-conditioned car to walk across South Franklin Street in Marshall to a modernistic blackish brick building sitting cater-corner on the southwest side of the intersection. Inside the main office suite, Franklin Jones, Sr., was on the couch visiting with his son and happily watching his subteen grandson hustle around the office carrying papers for the secretaries. The boy is half-English, and sounds it, and the older Jones cocked his head and tried to imitate him, without noticeable success. Jones senior is in retirement, and a cane helps him get around; in conversation he sounds downright mellow. But starting in the late 1920s as a workmen’s compensation lawyer, he terrorized railroads all over Texas.

My memory of him from the forties is of a fellow who was only a cut or so above being a town character, and my only regret now is that I didn’t listen to him more carefully in those days, for he made far more sense than the Dallas News or the Reader’s Digest, my primary sources of information. People joked about Jones: “Know the best way to improve the value of an old worn-out cow? Cross it with the Texas and Pacific Eagle [the T&P’s fast, main east-west train] and then hire Franklin Jones to bring your law suit.” Millard Cope, the Bourbon editor of the News Messenger, wouldn’t quote Jones in the news columns when he challenged an action of the sacrosanct city government, or the archconservatives who controlled the county and state Democratic organizations. But he did occasionally permit a long letter to the editor, which many people in town thought to be odd: why-ever would a grown man be so cantankerous? I remember no specifics, but Jones also reputedly had peculiar liberal ideas on Negroes.

Franklin Jones, Jr., sat behind a desk across the room, fidgeting with a letter opener and listening to his father. He is a lithe, sun-bronzed man in his midforties who keeps in shape by swimming a mile daily at his private pool. I had not seen “Soupy” Jones since an Alpha Tau Omega fraternity rush party at the University of Texas in 1952; he was a law student, I a green freshman. He had just injured his wrist in a shotgun accident, and we sat on a porch and drank Schlitz from cans and talked about Caddo Lake and people we knew. Three years my senior, Soupy graduated from the UT law school and returned to Marshall and joined the firm his grandfather had founded early in the century. A few years later a cousin, Scott Baldwin, also joined the firm. By coincidence, Scotty Baldwin’s grandfather had also been a partner of the first Jones, and the close family bonds are obvious. When an anecdote begins—and both Baldwin and Soupy are vivid raconteurs—one talks a few sentences, pauses, the other picks up the story to tell his part.

“Yeah, things have changed,” the junior Jones said. “But a lot depends on where you have a case. Houston, for instance, is a Baghdad for personal injury lawyers. It’s an industrial city, with many working people who appreciate the dangers of the work place. Juries will listen to you there, because these people have worked in the steel-fabricating plants and the petrochemical complexes, and they know what it’s like to drive a truck. You can get good verdicts there. The insurance companies know it, and they are prone to settle a Houston case out of court.

“Dallas, now, is a different story entirely. It’s a Sahara compared to Houston. Dallas is an insurance center, and the entire community is against you in a PI case, because all these little clerks and file shufflers are taught to believe that if the insurance companies pay out money, it will ‘hurt the company.’ An insurance functionary—a guy with a big title and a small salary—loves to go back to the office and write a memo telling his boss that he ‘did the right thing’ and refused to vote damages. So, if we get a Dallas case, we do everything possible to avoid filing there. Move the trial anywhere at all, spare me Dallas.”

An interruption. A secretary announced the arrival of lawyers to take depositions from a Jones’ client, a truck service manager who suffered grave injuries when a butane truck overturned on a curve during a test drive. Chris Harvey is from the Dallas superfirm of Strasburger, Price, Kelton, Martin and Unis, which has the reputation of being perhaps the best insurance defense office in Texas. Pike Powers, Jr., a round-faced man in his thirties, is from another insurance defense firm, Strong, Pipkin, Nelson, Parker and Powers, in Beaumont. “Here’s the enemy!” exclaimed Jones, going to the door to greet the visitors. (The “enemy” had spent the last hour in private offices in the Jones, Jones & Baldwin suite, using the telephone, reviewing files, and acting at home. PI and defense lawyers fight vigorously, even viciously, in court, but in most instances they are unfailingly courteous in their personal dealings.) Powers exchanged folksy banter with Jones senior, saying that his partner, Charles Pipkin, “told me to be sure and say hello to you.” Jones beamed. “That old devil. We’ve been round and round in many a courthouse. He always acts nervous, as if the worst is about to happen. One thing old Pipkin was good at—tell me, how old is he now?” “Eighty-two,” Powers replied. “—was losing papers. You’d get into an area that was hurting him, and crash!—a whole file of papers would fall on the floor and scatter every which away. Pipkin would be on his hands and knees, hunting them down, saying, ‘I’m sorry, your honor,’ and I’d be fumin’, ‘cause I knew why it happened. It’d take five minutes for things to calm down and longer than that to get your witness back to where you had him. A sly old devil.”

Everyone laughed, so Jones senior told another story, this one about the witness who was called to the stand and asked if he swore to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. “I won’t lie,” the fellow replied. “I’ll leave that to my lawyers.”

Jones junior and the two visiting lawyers gathered their papers and we adjourned to a conference room where the deposition was to be taken. Jones took me around to another office to meet his client, a slender man in his thirties in a Western-style knit suit; vicious scars were visible under his open-necked shirt, and others crisscrossed his face. Jones briefed him on what was to happen. “If you don’t understand a question, and you answer, you are going to make a mistake. Be forthright and honest, and answer as completely as you can. OK?”

“OK,” said, the client. He took the last nervous puff off a cigarette and followed us around the corner. (Jones earlier had told me of his physical condition: back and other injuries that made him permanently unfit to work, although he had tried. The outcome of the suit, in all probability, would determine whether he had an income for the rest of his life, or whether he would subsist on welfare.)

Depositions are tedious affairs, with lawyers probing for elusive facts, trying to pin witnesses down to exact statements and to prod them into providing information that might knock the bottom out of the lawsuit. Pike Powers, however, began his questioning of Jones’ client as if he were chatting with a friendly neighbor.

“All right if I call you Junior?” he asked. “Apparently everybody else does.”

Junior shrugged. “OK with me—done it all my life.”

Powers traced Junior’s personal and work history, mainly by tracking over answers that Jones had supplied earlier to written interrogatories. He got a bit more precise on Junior’s tickets for speeding and his 31-day hospitalization for a back injury after an accident in the sixties—one attempted trap Powers was unable to spring. He took Junior through a long recitation of his truck service career, from back-shop grease monkey to shop manager. Yes, Junior said, part of a manger’s job was sedentary—paper and telephone work. Oh? Well, what percentage of your time was actual mechanic work? Sixty per cent, Junior replied. Poof. Powers couldn’t make a deskman of Junior.

But Powers did score two points: (1) Junior earned about as much the few months he worked after the accident as he did the preceding ones, and (2) he had suffered blackout spells the year before the truck wreck. (Jones warned me in advance: “All they can do is try to show blacked out and rolled the truck. They’ll try, but they can’t do it.”) But Junior survived questions about past heavy drinking. Yes, he knocked off a bottle of vodka daily at one time, but he “quit cold” after an ulcer operation in 1965.

At noon we sent out for a lunch of sliced barbecue beef, pinto beans, and coleslaw. Jones told Powers that he thought the deposition should continue without interruption: “I believe you’ll wear out quicker if you don’t eat.” Powers laughed. “Main, I ain’t been mean.”

Well, he hadn’t, but he had established that Junior quit three jobs after the accident, even though the employer had said nothing about dissatisfaction with his performance. Should the case go to trial, the defense lawyers could point to Junior as an accident-prone man with a record for speeding violations, a past history of heavy drinking, and documented spells where he blacked out without seeming cause. Was he also a malingerer who decided to parlay an admittedly serious accident into a lifetime of annuity? Such was the groundwork that Pike Powers laid before the barbecue break. But could he overcome the rest of Junior’s story—that the steering wheel “just wouldn’t respond,” that he hollered, “Get out!” to his passenger and hit both hand and foot brakes and shifted down thirteen gear stops, only to have the truck roll anyway? And that after his release from the hospital “setting hurts me, standing hurts me, the pain in my back makes it unbearable at the end of the day”? (Six months later a jury awarded Junior $650,000; the widow and son of the man killed received $450,000. Jones, Jones & Baldwin’s share: between $350,000 and $400,000, less expenses.)

The after-lunch questions dragged, and I thought of other things to do on an East Texas summer afternoon, and said my goodbyes. Back in Marshall a week later I returned to Jones, Jones & Baldwin for a talk with Scott Baldwin. Baldwin has problems. A progressive spinal disease bends him over, and he is constantly in motion, even as he sits in a chair, trying to get comfortable. The son of “old Doctor Baldwin,” I remembered him as darkly handsome, if somewhat diminutive, a good high school athlete who always seemed to be smiling. My older sister was his contemporary, and I know at least three of her high school friends who would have sworn lasting love to him—had Scotty ever noticed them; he didn’t. Now I realized that this man with the flashing eyes, with the soft-hued summer slacks and open-necked shirt, sitting in a law office across from the old site of Maranto’s Grocery in downtown Marshall—population, 29,000—makes probably as much money in a year as a partner in Cravath, Swaine & Moore, the New York corporate firm, or the fabled Washington superlawyers Clark Clifford and Lloyd Cutler, and certainly as much as the PI people I’d met earlier in the hotshot personal injury towns of Cleveland, Chicago, and Detroit.

“How did we get where we are? By being willing to go down to the courthouse and try cases, that’s how. We have tried twenty to thirty a year to jury verdicts—and I mean jury verdicts, and not those situations where the other side settles up at the courthouse door.

“The federal district courts in East Texas sit in a town only a week or two at a time, which means you get kind of busy during a session. Franklin and I have had situations where we’ll have one jury out deliberating; we’ll be putting on evidence in a second case; and during the recesses we’ll be picking a jury in a third case. It’s a gut-checking experience, to have a jury verdict come in while you’re trying another case. The judge puts the working jury back into the spectator seats and receives the verdict. If it’s good, OK. But oh, man, to have a bad one come in during a trial—you can’t help but wonder what effect this has on your current law suit: I mean, you’ve tried one and lost it, and the other jury says, ‘Well, they brought one bad one, maybe they’ve brought two bad ones.’ Taking the other jury out of the courtroom doesn’t do anything. In a small town, everybody around the courthouse, even the jurors, knows what happens in a trial.”

So how do Jones and Baldwin go about constructing a personal injury case and presenting it to a jury? Personal injury lawyers invariably assert that suits are won long before they reach the courtroom—that the side that does the best advance preparation is going to win. Another dictum is that the more money involved in a case, the higher the quality of the lawyers on each side—especially the defense. “When you go up against Lloyd’s of London or Travelers Insurance,” Jones said, “you see the best defense money can buy. I like it that way. I would always rather try against a good lawyer.”

I asked the cousins for a trial transcript of a case that illustrated how they go about their work, and when I flew back to Washington my suitcase contained a seventeen-pound multi-thousand-page file, Steven Paul Gandy v. Verson Allsteel Press Company, tried in the Marshall division of the U.S. District Court March 29 through April 1, 1976. Gandy, 22, was preparing to finish his last year at the University of Texas; after graduation he planned to enter the plant nursery business with his brother, in his hometown of Tyler. He took a summer job in 1974 at a Carrier Air Conditioning plant in Tyler, operating a press brake that would crimp or fold sheet metal against a die. Carrier had bought the machine from Verson the preceding year for $14,064.75. It was wired to operate with either of two control switches: a foot pedal, contained in a recessed box; or two push buttons, located so far apart that the operator had to use both hands to depress them simultaneously. Carrier installed the machine with only the foot pedal.

A supervisor trained Gandy for one day; the next night he went to work on the 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. graveyard shift. The press gave Gandy problems. Several times during the night, according to his later testimony, the machine “double-stroked”—that is, the ram would come down twice or more when he depressed the foot pedal, rather than once. He consulted a supervisor, who tinkered with the machine, then told him to keep working.

At six o’clock in the morning the press slammed down on Gandy’s hands with a force of 60 to 65 tons. Gandy lost both hands. Jones and Baldwin sued Verson for $2,500,000, charging that its machine was dangerously defective on three grounds: that it did not have an effective guard, that it would make unplanned strokes, that the warning on the face of the machine was inadequate.

Why did they sue Verson, rather than Carrier? “The workmen’s comp thing,” said Jones. “Carrier had paid his medical bills and thousands of dollars for the work time he missed. Also, it’s much harder to prove gross negligence on the part of an employer than it is on the part of a manufacturer. Verson let the press brake out of its plant in unreasonably dangerous condition, that’s all we had to prove.”

Cardinal rule number one for a plaintiffs lawyer is to make maximum use of the client’s disability, even if flaunting the injury makes him uncomfortable in the courtroom. In the words of a Philadelphia negligence lawyer, “I’m not adverse to making a man feel bad about himself for the course of the trial if the end result is to get him several hundreds of thousands of dollars.” Gandy came to court without his artificial hands, and Baldwin, during his opening statement, told the jurors they should be thinking about big money as the trial progressed, for the plaintiff deserved it:

I will ask you to consider what the value is of a man going through life without his hands and think about it during the course of this trial, at night, and when you wake up . . .

We take our hands for granted. The simple matter of rubbing your nose or rubbing your eye, opening a door, holding the hand of a frightened child, the list is as long as your imagination is. I can give you a hundred things now that he can’t do, and that is not even a part of it . . .

Think about it and prepare yourself for your decision, and I think that you will agree with me that he had the God-given right of going through life a whole man and that a verdict of $2,500,000 is a reasonable verdict, when you consider what this man has lost, that is, his manhood, his hands, the parts of his body he uses the most.

A San Francisco defense lawyer once told me, “You can defend sprained-back cases all day long and not worry, because the jury can’t see the injury. But I tell my clients [insurance companies], ‘If the person suing you comes to court with a leg missing, or a big scar across his face, write out a check on the spot, don’t waste our time with a jury.’ ” Thus, Verson’s lead defense counsel, Tom Alexander, had to counter the sympathies of the jurors as they looked at his handless opponent. “Mr. Baldwin, who is a wonderful lawyer, has made a beautiful appeal without much reference to the actual evidence in the case,” Alexander said. “For instance, he asked each of you to think all the time about what Mr. Gandy can or cannot do.”

Alexander emphasized that the jurors must also concentrate on whether the press was defective:

You really must steel yourself to appeals of sympathy. For instance, every time I have seen Mr. Gandy he has had prosthetic devices on his hands and he uses them very well. There can be no reason for his appearing here today without them other than a direct appeal to sympathy . . . while you are trying to discharge your duty to this court to decide the facts in this case . . .

This machine [the press brake] is a well-thought-out machine, well planned, has stood the test of time, and if you, as jurors, let your mind get so obscured that you don’t pay attention to the evidence about the machine itself, it is going to be awfully difficult for you at the end of this case . . . to decide . . . was this machine defective when it left Verson’s control?

Gandy, the first witness, described how the press brake worked: “What you do, you put a piece of metal in there and it had a blade kind of like a guillotine and it would come down-and crush the piece of metal into a desired shape.” The process was supposed to flick finished pieces of metal through the machine to a basket, but some landed off to the side. “So after they would get three or four in there I would reach my hand through and put them in the basket.” A foreman told the workmen to do it this way, Gandy said.

I was cleaning off the back of the die and my foot was out of the foot valve [the triggering mechanism] and for some reason the machine came down again and when it did I saw what it had done, I screamed . . .

Gandy went on to describe how he looked down and saw his hands hanging from his wrists by shreds of skin. Yes, he said, the machine had “misfired” several times during the shift, and he had complained to a supervisor, who tinkered with it. No, he had received no briefing on safety, nor had he been given any operating manuals for the machine.

Why wasn’t Gandy wearing his artificial hands to court? They were heavy, he replied, and made his stumps sore, and he could wear them only about half the time. How did you feel? The pain was “constantly burning.” There were impulses when he would reach with nonexistent hands—only to realize there was nothing with which to reach and nothing to touch if he could. There were nightmares from which he awoke screaming and crying. Gandy seldom went out because he was embarrassed. People would come up to him on the street and “ask me what happened, why I am like that; they have no concern for my feelings whatsoever.”

Baldwin put into evidence a list of 150 things that Gandy said he could no longer do. His dream of being a nurseryman was over. “You have to hoe, plow, trim trees, you have to use snips, you have to graft, you have to bud. . . .” None of these could be done by a man with artificial hands. Baldwin turned the witness over to Alexander for cross-examination.

A lawyer who roughs up a pitiable witness risks alienating jurors, so Alexander walked carefully. Yes, Gandy did remember a sign on the machine, “Never put any part of your body under the ram or within the die area.” No, Carrier had not instructed him on proper use of the machine. Didn’t his own violation of safety rules cause the accident? No, the machine “misfired,” and a superior had told him to clear away the finished metal with his hands.

Whatever headway Alexander made was dashed by Baldwin with the single question he asked on further examination.

Baldwin: Would you mind pulling up your sleeves and showing the portions of your arms so we can know just what parts of your arms were amputated?

Gandy: I can’t.

The Court: He can’t hold them up. You will have to do it for him.

[Whereupon the witness’ sleeves were pulled up and his arms exhibited to the jury.]

Baldwin : I have no further questions. Your Honor.

Next, Baldwin put on two technical witnesses, Paul F. Youngdahl, a mechanical engineer from Palo Alto, California, and Richard Fox, an engineering professor from Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. Both avowed that the press brake should have come with a barrier guard or an electric eye to prevent the operator from putting his hands into a dangerous area; they claimed a number of fail-safe devices were available at minimal cost.

Yes, said Alexander, but is it not true that standards set by the Federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI), an industry group, require that the employer provide guards and ensure their usage? Perhaps, said Youngdahl, but the manufacturer, with his special expertise, is best qualified to design and install the guards. (Jones and Baldwin knew the defense would cite the OSHA and ANSI standards, so they primed the jury to ignore the issue. Baldwin said in his opening statement that the standards “are not enforceable, they are voluntary . . . they are largely written by industry, the very people who sell these machines.”) Then Alexander got tough. He depicted Youngdahl and Fox as professional witnesses who would testify to anything for a fee—and not very capably, either. He expressed surprise that Fox had appeared as a witness in 138 personal injury cases in five years. He was astounded that Youngdahl hadn’t even visited the Carrier plant during his accident “investigation.”

Youngdahl: It was not important to reach an opinion about this Verson press brake.

Alexander: Well, sir, I wasn’t talking about reaching an opinion. Actually, you reach your opinion in many, many cases right off the bat, don’t you? These people know where to hunt for somebody who will say a machine is defective.

Baldwin objected, and Judge Joe J. Fisher sustained him. So Alexander tried a slightly different tack. How many cases had Youngdahl appeared in during the last year? “Perhaps fifty in the past year, in one way or another.” Alexander huffed, “Will you be surprised to know that’s more cases than I have, and law is my full-time occupation?” Judge Fisher cut him off even before Baldwin objected, saying the point was “immaterial and irrelevant.” Alexander could not resist a parting shot. He asked Youngdahl, “You would imagine that there are quite a few [engineers] closer to Marshall, Texas, than Palo Alto, California, who are qualified engineers and who have actually had experience with presses?” (Several days later, in his closing argument, Alexander used even stronger language. Fox, he said, “has appeared as an expert witness on plastic toy horses, on bicycle seats, on Exercycles, on tailgate accidents, automobile accidents, every kind. Whenever anybody has any kind of an injury, Mr. Fox is willing to show up.”)

Alexander’s chief expert witness was Kirk Lunser, manager for electrical engineering for Verson. Lunser was direct. Five or six components would have to fail before the press malfunctioned. “Outside and inside experts” checked the press immediately after Gandy’s accident and found nothing wrong with it. Even when they tried they could not make it double-stroke.

“All right, sir,” Alexander asked, “do you know of anybody that could perceive it better than you, who designed and built the press?”

“I don’t know, sir,” Lunser replied. Unfortunately for Lunser, Jones and Baldwin had done some quiet research on patents that Verson and its engineers obtained over the years, a laborious task that involved reviewing thousands of pages of technical documents. The effort was worth it. Baldwin casually read language that Lunser used in a patent application for a press safety device, but which had not been installed on the Carrier press:

The press control circuits heretofore developed have left much to be desired from the standpoint of safety. For example, the run control push buttons referred to at the operator control station are often subject to a great deal of abuse, which can cause undesired grounding or short circuits in the various contacts operated by the control punch button.

In such cases, it is readily possible that the press ram can be operated by the pressing of only one or less than all of the control buttons . . . or the press ram can operate continuously when it is supposed to stop automatically after one cycle of operation, placing an operator in the path of the movement of the press ram in great danger.

“I spoke those last words loud and slow and clear,” Baldwin said later, “and the jury heard me. There we had it, in Verson’s own words: its presses are apt to double-stroke just the way we claimed it did when poor Steve Gandy lost his hands. This application language knocked the props out from under Verson.” All Lunser could say in rebuttal was, “We protect for something that is nearly impossible, to be doubly safe, sir.”

Baldwin gave Lunser one last ruffle before letting him off the stand, bringing out that he was neither a college graduate nor a licensed engineer. “My own experts had degrees festooned all over them. This was a way of suggesting to the jury that Verson wasn’t the big efficient do-nothing-wrong corporation it claimed to be.”

Another Verson expert witness, Frank Holland, a “consultant engineer,” also called the press brake safe. He blamed the accident on Carrier, for not properly training operators, and on Gandy himself. Holland felt Gandy was tired at 6 a.m.—he too had once worked a graveyard shift—and perhaps even unknowingly had “shifted his foot onto the press switch.”

Jones did the cross-examination this time, and in short order a flustered Holland found himself in a box, trying to explain away more language from the past that had the net effect of bolstering Gandy’s case. Jones baited the trap carefully. First he had Holland insist that chances of a machine malfunction were “perhaps a billion to one or something like that,” that Gandy most likely activated it accidentally. Jones lulled Holland along with innocuous questions. “I wanted him to think he was home free, that I couldn’t touch him. Then, zip.”

Jones: Let me ask you if you agree with this point, Mr. Holland, or this statement: “A good starting point in the design of a press control is to assume that each relay push button valve and limit switch is going to fail some day, in either an open or a closed condition.” [According to Jones, “Holland got a sheepish look on his face, as if he knew something awful was about to happen to him.”]

Holland: Yes, that sounds to me like a talk that I gave at the National Safety Congress in 1966.

Jones (smiling): I wondered if you would recognize it . . . Do you also recall telling them that . . . [equipment failure] is not too unrealistic a premise, because in many stamping plants there is little, if any, preventive maintenance of electrical controls?

Holland: Right.

Jones: So right there you were saying that the employer couldn’t be relied on to take care of these electrical controls and the designer had to consider that fact, weren’t you?

Holland: Yes, sir, and the designer did. I also stated earlier that I was very pleased to see what had been done to protect against failures.

Snap. Jones ticked off a long list of specific safety devices that Holland had recommended for presses. None had been on the machine that injured Gandy. He read another paragraph of Holland’s speech: “The designer of the press control must also remember that the human mind of even the most conscientious operator is going to wander away from the job at times and that some operators would use all of their ingenuity . . . to defeat any safety control or guarding installed on a press. To them it is like a game, like Russian roulette.” Responding to other questions, Holland admitted he was giving this advice to press manufacturers, not to employers.

Jones: Did you also tell them, sir, when foot switches are used that the dies should be shielded with suitable guards or the foot switch should be located far enough away that the operator cannot reach any . . . point on the press?

Holland: Yes, I said that.

Holland continued to insist that installing the safety gear was the employer’s responsibility, not the manufacturer’s. But as Jones recollected, “The jury wasn’t listening to him anymore. They had heard Verson’s own witness say that Verson had turned loose a machine that could maim a man. Under strict liability, that is all we had to prove.”

Both sides called witnesses who gave contradictory testimony on whether the press brake did or did not malfunction. Gandy witnesses said the machine double-stroked for as long as 45 seconds, and that repairmen had to be called to turn it off. Other co-workers, testifying for Verson, called the press brake safe. A maxim of PI law is that if a witness hurts you in one area, have him talk about something else on cross-examination, so Baldwin didn’t quibble with a witness who was voluble on behalf of the defense. He simply asked a series of questions about the accident scene: “You had a horrible injury there, didn’t you? Did you see the flesh and the blood and bones? And he obviously was in pain, wasn’t he? Were his hands just hanging on by the skin?” Now defense lawyer Alexander tried a diversion of his own.

Alexander: You had an occasion to talk to Mr. Baldwin about this accident before, have you not?

Williams: Yes, sir, I have.

Alexander: Where was that?

Williams: Garland, I believe it was at the Ramada Inn.

Alexander: How long ago was that?

Williams: Maybe a month, maybe a little more, I am not sure.

Alexander: Were you subpoenaed to come here?

Williams: Yes, sir, I was.

Alexander: You never refused to come for Mr. Baldwin or anybody else, did you?

Williams: No, sir.

Alexander’s clear implication was that Baldwin had tried to keep the jury from hearing testimony damaging to his client. But, as Baldwin put it later, “the defense attorney got greedy.”

Baldwin: I have a few questions. What does Mr. Baldwin look like?

Williams: Well, I say Mr. Baldwin, he was—I don’t see him in the courtroom.

[Whereupon there was laughter in the courtroom.]

Baldwin: Thank you.

Alexander by now was clearly on the defensive, with Jones and Baldwin eliciting damaging testimony time and again from his own witnesses. Alexander put on the Carrier purchasing agent, Robert L. Wilkerson, so that he could get into evidence a letter of purchase from Verson stating that guards were not included with the press, and that it was the employer’s responsibility to provide “guard devices, tools, or other means” to protect workers against “serious injury.” Wilkerson also said Carrier chose to install the machine without the two-hand press controls, relying instead on the foot pedal.

In short order Baldwin had Wilkerson admit that one reason he bought the Verson machine was because it was cheaper without the safety guards.

Baldwin: It was a savings to Verson to sell this machine without a guard, wasn’t it?

Wilkerson: I would think so.

Baldwin: And for whatever the reason, this machine was manufactured and sold without any character of a guard on it or safety device, wasn’t it?

Wilkerson: Yes, sir . . . they have made the policy that you buy it without the point of operation guard.

Wilkerson also said that after Gandy’s tragedy, Carrier decided to put a protective barrier on all punch presses in its factory to prevent similar accidents in the future.

The record suggests that Alexander now realized his client was in for a rough time when the jury retired, and all that he could do was to try to hold down the amount of damages. Thus, he put into the record a physician’s report from the Texas Institute for Rehabilitation and Research (TIRR) where Gandy had been outfitted with artificial limbs. The report declared Gandy was adjusting well to the prosthetic devices and that he suffered no “significant pain on his stumps,” which had healed well. So far, so good, but the finding contradicted Gandy’s testimony about his inability to use the metal limbs; and if Gandy played loose with the truth on one point, was his story of the malfunctioning press believable?

Unfortunately for Alexander—and Verson—the report discussed other matters as well, and the entire document went into the record. The report said that Gandy had planned to finish college before marrying. “Two weeks after his injury, Steven went ahead and married his fiancée because ‘he needed her after what had happened.’ His wife, Jane, accompanied him to TIRR. She is a sixteen-year-old high school student.”

Jones said, “When Alexander read that in court, Gandy went absolutely white. He leaned over and said, ‘That’s a lie.’ I was afraid he was going to blow up, he was so shaken.” I told him to calm down, that he’d have a chance to rebut the report when he went back on the stand.”

The defense lawyers either did not notice Gandy’s emotional reaction or misinterpreted it. Jones and Baldwin gambled. When they recalled Gandy, he was asked only about work rules; not a word was said about the physician’s report. They sat back to see what Alexander would do.

Blam. Early on Alexander asked whether the report was accurate in describing what he could do with the prosthetic devices. Gandy squirmed in his seat. “The look that came over his face is something that I’ve never seen before, that of a man in sheer agony,” Jones said. “I thought to myself, ‘Either he’s going to explode, or he’s going to knock this lawyer right on his ass.’ ”

Gandy: Well, from listening to you, a person could be—I mean you couldn’t understand it correctly, no sir.

Alexander: You say the record is inaccurate?

[Jones, re-creating: “Gandy was right on the edge of the witness chair. He was hurting. What had been said about his marriage had offended him, I think, even more than the loss of his hands.”]

Gandy: Well, I loved my wife, and I didn’t marry her because I needed her in that effect. I married her because I loved her.

Jones glanced at the jury. Tears rolled down a woman’s face. Several men cast distinctive frowns toward the defense table. Gandy quivered, but he said nothing more. Alexander ended his questioning.

The jury went out at 9:10 a.m. on April 1. It broke for lunch, then returned at 2:48 p.m. with a verdict of $561,200. Judge Fisher agreed with the finding. “The court feels you have reached a fair and just verdict. The court might have awarded more damages if it had been submitted to the court. On the other hand, another jury might have awarded less damages.” The insurance lawyers did not appeal, and Gandy received his money, less $22,391.98 that Carrier had paid for medical bills. And, of course, less 35 per cent to Jones, Jones & Baldwin.

- More About:

- Books

- Longreads

- Marshall

- East Texas