This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Local news has changed a great deal in the twenty-plus years since I worked in it; local stations are big money-makers now (they weren’t then), and the owners and managers have called in the consultants and the accountants, who have changed the local scene. But one thing hasn’t changed: local radio and television are still the places where broadcast reporters learn their craft. And though it’s true that you can find some bad values in local stations—a lot of sloppiness, silliness, cheapness, and hype—it’s also true that the newspaper world is no different. Journalism has always suffered from such sins (ask William Randolph Hearst) and probably always will (ask Rupert Murdoch). So to begin with, let’s not pretend the newspaper world is any better and let’s not pretend it produces better journalism.

Local TV and radio taught me how to find a story, how to ask questions, how to show some aplomb in front of a mike and in front of a camera; it taught me how to work in a studio and how to work with a crew; it taught me how to work the flood, the fire, the bus accident, and the embezzlement case at city hall. I came in fresh, fat, and—Lord, I hate to say it—rather sweet. It was at a local station that I learned what all reporters have to learn: how to wear skepticism like a hat that you never take off. Except in church. Maybe.

The station was KTRH in Houston, the 50,000-watt “Voice of the Golden Gulf Coast.” I wound up there after knocking around a bit in Houston journalism. I’d worked at Huntsville’s KSAM radio—250 watts, “the Pride of Walker County.” Then, after I got out of the Marines, I thought I had a job on one of the Citizen chain of newspapers—a nice little pork-chop paper with page after page of food-store ads and a news hole the size of a pea.

At the last minute I didn’t get the job. So I hung around the Houston Chronicle, and it was clear I would get nowhere, even with a city editor as benevolent as Dan Cobb.

Then I heard that KTRH had an opening. I was hired by Bob Hart, your basic gruff and demanding hard-news guy. Bob was the prototype of all-news radio—he was all news all the time and he never stopped. He was hard-charging, hardboiled, and—you guessed it—a soft touch. I lobbied him for three months, pestered him, waited for him in the lobby, called him, wrote him, and pleaded with him. Eventually he hired me because I wouldn’t give up. That, naturally, is what he wanted in a reporter. He figured I was a diamond in the rough. I think I turned out to be a little rougher than he’d anticipated.

I wanted to be part of the news staff. It turned out I was the news staff. My first day, I walked in and asked where I should go, what beat I’d be assigned to. Bob Hart told me that maybe it would be a good idea if I checked things out at city hall, the county courthouse, the emergency room at Jeff Davis charity hospital—and then maybe I could drop by 61 Riesner Street, the police headquarters.

And that’s what I did. My itinerary was expanded to include the mayor’s office, where I got to know Oscar Holcombe and Roy Hofheinz, and the county commissioners’ office, where E. A. “Squatty” Lyons held forth. I mention all these places because they’re where I learned to be a reporter.

At first I just walked in and introduced myself and sat down and listened. But with time I learned to stop nodding and start asking questions. Then I learned to ask the right questions. And with time I learned to turn it into a story.

I’ll tell you what a local station did for me—it knocked a lot of naiveté out of me and knocked a lot of journalistic sense into me. It can be wild and woolly, the local experience, and it’s not the way they teach it in grad school, but we had room to learn and grow—and make mistakes. These days I meet young reporters and producers and I ask them where they’re from and they say “Columbia J School” and “University of Missouri Journalism.” That’s nice, but I’d feel better if some of them had studied under Professor Squatty Lyons!

Bob Hart himself was part of my education. He knew the city’s structure—its substructure and infrastructure—and he knew who was just a Big Hat and who had real power even though he wasn’t famous. He tipped me to who was what and what it meant. And he went over my scripts, teaching me to compress and condense what I knew. People forget that radio is a training ground for television journalists—but it’s true. In radio all you have is words. In television the audience is enthralled by the picture and they think the word is secondary. But in radio, words are it, and radio is still the place where broadcast journalists learn to write. Charles Osgood is one of the best network writers, and he learned his trade at a local radio station—WCBS in New York.

But back to KTRH. In those days, in order to give a feeling of You Are There to some of our broadcasts, we’d report live from the city room of the Houston Chronicle, a big, ugly, poorly lit, paper-strewn, coffee-stained monster of a room with big brown stains on the ceiling above the chain smokers’ desks. The place was redolent of bourbon and broken dreams, full of people who were charming and amusing, kind and cynical, nasty and competitive. It was a wonderful place to meet and learn from the older guys. There I was with my jaws flapping into a mike plugged into a jack on the floor of the heart of Houston journalism! Oh, I felt so plugged in, too, so able to get the story and tell it, so at the center of things, and so surrounded by the best. And I was. Dan Cobb, the city editor’s city editor. Walter Mansell and Everett Collier, two great political reporters. Ann Hodges, a general-assignment reporter who could handle anything with competence and gentleness. Gentleness, in a newsroom! And Zarko Franks on rewrite. Zarko was an artist. He could take some measly one-alarmer and turn it into the Chicago Fire—here’s some guy phoning in that a cushion went up in flames on some sofa in some one-bedroom across town, and by the time Zarko was done with it you could smell Mrs. O’Leary’s cow turning on the spit. (I love it when print reporters talk about TV’s penchant for sensationalism.)

I spent ten wonderful years in radio. Then I went to KHOU in Houston. Television was so primitive in those days that when I did the ten o’clock news, it was just me and a slave camera and one technician somewhere deep in the bowels of the building. I had to push one button to cue up a commercial and another to run film of a news conference and all the while keep my place in the script and try to look and sound convincing. I was anchor, reporter, writer, editor, and technician on that show. And to the extent that I can handle a studio now, that’s where I learned it.

Just one more thing I want to say about local stations: some of the reporters there are the best. There are a lot of veterans of broadcasting who stay at local stations because they like it, because they know local is closest to people’s lives and the impact you can have on the local scene is more direct and usually more dramatic than the impact you can have nationally. Local is where you can change things. And the rewards are great. So these veterans settle down with their families and become part of the community, residents who have a real stake in the place they report about. Some of them are doing the most important work in the business.

And then there are the young ones who are starting out and using local stations as a training ground, a place to learn and prove themselves, a springboard. They’re the ones who’ll make some big mistakes while they’re learning their craft. But it would be nice if viewers, when they watch them, would remember how it was when they first started out, selling their first couch or greeting their first client or whatever—and remember the mistakes they made the first few years. A little sympathy would be nice—and so would a little patience. They’re trying.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Houston Chronicle

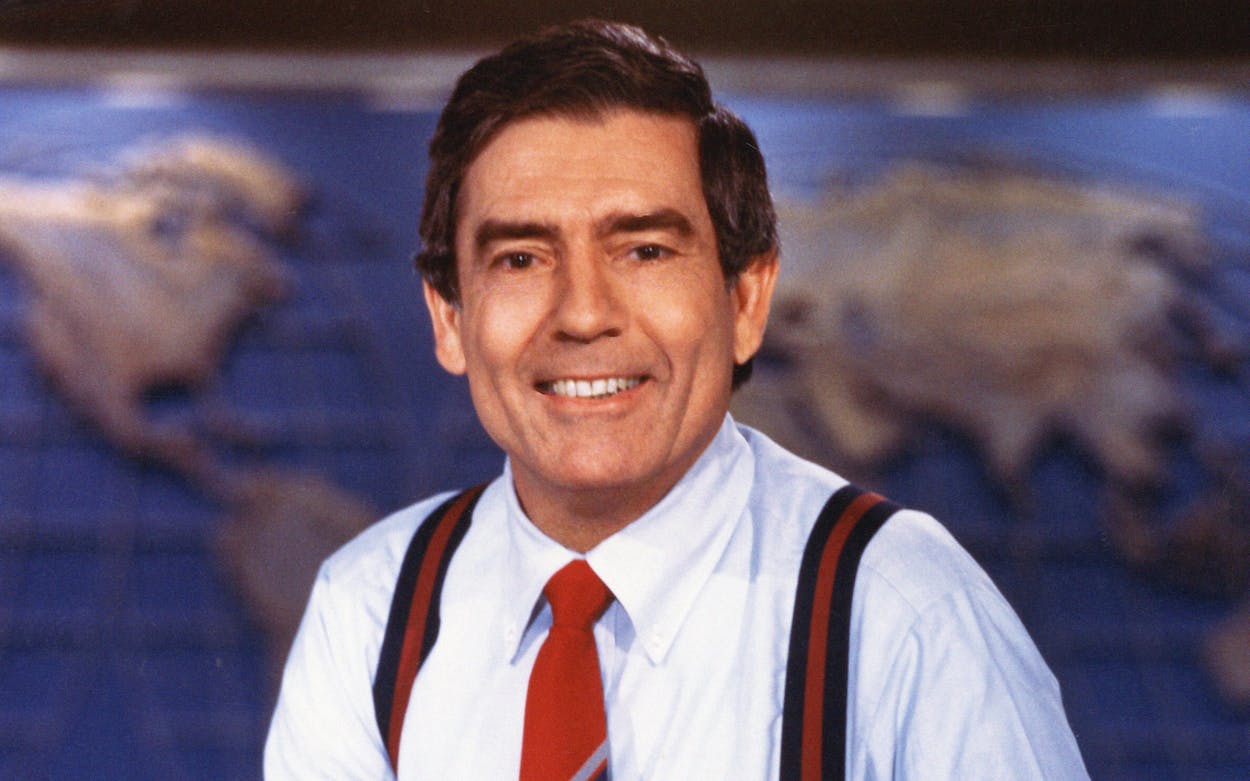

- Dan Rather

- Houston