Everybody loves a good redemption song, especially one with a lot of darkness. Billy Joe Shaver has a bunch of them. The singer-songwriter from Corsicana is one of the best the state has ever produced—the best, Willie Nelson told me in a profile I did on Billy Joe in December 2003 (“The Ballad of Billy Joe Shaver”). His wild life gave him plenty of material. There was the boozing, drugging, womanizing, and fighting in the seventies and eighties, when he was part of a long-haired Nashville Rat Pack of country music outlaws, well-known troublemakers like Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and Kris Kristofferson. “I was so goddam crazy,” Billy Joe told me. “I was crazier than any of them. I went for it.” Billy Joe’s wild ride continued into the nineties; he actually had a heart attack onstage in 2001 and almost died. This came at the end of a period of unfathomable sadness. First he buried the love of his life, Brenda, a woman he had married three different times, after she died of cancer in 1999. A year later his only son—a troubled soul who had helped revive Billy Joe’s career in the nineties—died of a heroin overdose.

But Billy Joe made it through those times by writing some of the most spiritual country music anyone had ever heard, unbelievable songs of despair and hope. He had been born again, finding strength in Jesus and reforming his ways, something he has never tired of reminding his audience. “I thank Jesus Christ every chance I get,” he often said from the stage. After a set filled with odes to the wild life, he ended his shows with the song, “You Just Can’t Beat Jesus Christ.” This is Billy Joe’s charm: the dark and the light, the bad and the good, a battle for his soul that you witnessed every time he performed.

So when he shot a man in the face in a bar three years ago, I wasn’t all that surprised. The circumstances of that night seemed straight out of one of Billy Joe’s songs. The shooting happened on March 31, 2007, when Billy Joe and his ex-wife Wanda went to Papa Joe’s Texas Saloon in Lorena, just south of Waco, after a day spent taking photographs for the cover of his next album. At the bar Billy Joe was introduced to a man named Billy Coker, a TXU Energy employee who, it turned out, had a cousin who had previously been married to Wanda—and who had killed himself. From this point on, the evening went downhill, though exactly how and why was a matter of dispute. The night ended in the bar’s back patio, where Billy Joe shot Billy Coker in the face. The .22-caliber bullet entered his upper lip, knocked out a tooth and a crown, and ended up in the back of his neck (doctors left it there because it was so close to his carotid artery). Billy Joe was indicted for aggravated assault with a deadly weapon.

It seemed like Billy Joe’s hell-raising had finally caught with him—how would he escape this one? He hadn’t shot the guy in the arm or leg or stomach—he’d got him in the face from four feet away. I had heard about his temper from old friends. “I’ve seen him fly off the handle at something he takes completely out of context,” one told me. Then there were the witnesses: the bar owner, who said Billy Joe had instigated the whole thing, tapping Billy on the shoulder and asking him to go outside. Two beer drinkers on the patio said Billy had no weapon and wasn’t provoking Billy Joe. One said Billy Joe and Billy had walked out and Billy Joe Shaver said, “Don’t nobody tell me to shut up. Where do you want it?” Billy testified that he had said in response, “Where do I want what?” when Shaver let his pistol do the talking. One of the patio witnesses said he heard Billy Joe say to Wanda, “I’m tired of this crap happening every time we go somewhere. I’m leaving. You coming?” Another witness to the aftermath said Billy Joe said to Billy, “Tell me you are sorry. You told me to shut up one too many times.” During final arguments, prosecutor Beth Toben said, “He may be a honky-tonk hero, and he may have written a lot of wonderful songs…but on that day, he was a honky-tonk bully.”

Billy Joe, though, had a lot of people on his side. For one, there was his attorney, Dick DeGuerin, one of the great old-school defense lawyers, who was working pro bono. Then there were Billy Joe’s pals Willie Nelson and Robert Duvall, who showed up to support their buddy and sat through hours of testimony in the first two rows. During a break, Willie told reporters, “We are just here to support our good friend, Billy Joe Shaver. We have been friends forever, always will be. I don’t think Billy Joe would do anything wrong. I think whatever happened was not his fault.” The defendant was backed up by a witness of his own, who testified that Billy went after Billy Joe with a knife but that the singer backed away. “To me it looked like [Billy Joe] was just trying to…to get away before firing.”

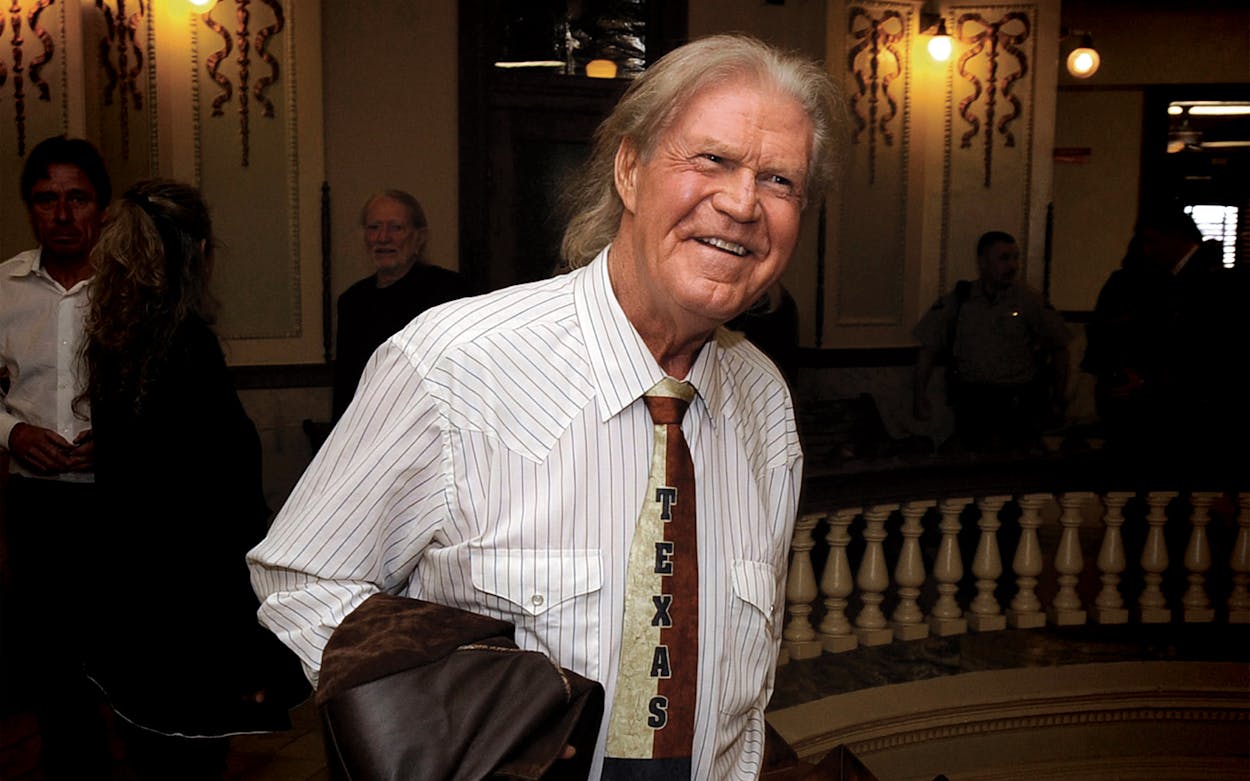

Then there was Billy Joe himself, with long white hair framing a craggy face and wearing a white shirt, tie, and brown leather coat. He testified that after Billy realized Wanda had been married to his dead cousin, the man shouted at Billy Joe to “shut the f—k up.” Billy Joe said the shooting was self-defense, that he had first gotten nervous when Billy stirred everyone’s beers and his own whiskey drink with a knife, then later wiped the blade on Billy Joe’s coat. According to Billy Joe, Billy was the one who had suggested they take it out back. “Being the John Wayne type of person that I am,” Billy Joe testified, “I went ahead and got to the door too.” He said he saw someone give Billy something that he thought was a gun, so he pulled out his pistol. “I wanted to scare him…wanted to beat him to the punch,” Billy Joe said. “I feared he was going to kill me.” Wanda said Billy had a knife in his hand when he asked them to go outside. Billy Joe said when they were together out back, he asked Billy, “Where do you want to do this? Why do you want to do this?” When Billy raised his arm, Billy Joe shot him.

Billy Joe got plenty of opportunities to charm the jury. When the prosecutor asked him why he didn’t leave the bar when the situation between him and Billy was getting worse, Billy Joe, in his deep drawl, replied, “Ma’am, I’m from Texas. If I were chickens—t, I would have left, but I’m not.” At another point the prosecutor said to Billy Joe, “The truth is, Mr. Shaver, you’ve had the reputation for being an outlaw your whole life, isn’t that right?” Billy Joe responded, “More like an outcast.” The prosecutor also asked if Billy Joe was jealous because Billy was talking to his wife, and the singer replied, “I get more women than a passenger train can haul. I’m not jealous.”

Billy Joe was found not guilty late Friday afternoon and stood around the front of the courthouse offering nice things about the man he shot. “I am very sorry about the incident,” Billy Joe said. “Hopefully things will work out where we become friends.” It was good Billy Joe, the man of God, the man who had made a mistake and was ready to move on.

Later that night, Billy Joe let his hair down at a show he did to an enthusiastic crowd at the Firehouse Saloon in Houston. Before he and his band played their first song, he amiably rolled up his sleeves and talked about the trial and the shooting. “It was good, man,” he said. “It’s good to win.” The crowd whooped its approval. “It’s so great because, they asked me, ‘What are you going to do about that boy you shot?’ I said, ‘I’m getting the damn bullet back.’ ” The crowd whooped even louder. “That’s true. You all think I’m joking? I mean it. Walking around being famous with my bullet in him. Stealing all my press. I think [the gun] shot itself.”

It was bad Billy Joe again—irresponsible, mean, every bit the bully the prosecutor had painted him as—all to the encouragement of a honky-tonk crowd. But as usual he caught himself. “Nah, it didn’t. I swear I’m sorry all that s—t happened, but it did.” He clasped his hands, looked heavenward, and continued. “And God was good enough and y’all were good enough with prayers and everything.”

Once again, everything was going to be all right. A minute later, he and the band started playing “Georgia on a Fast Train.” Billy Joe stomped, clapped, grabbed the mic stand, and started singing.