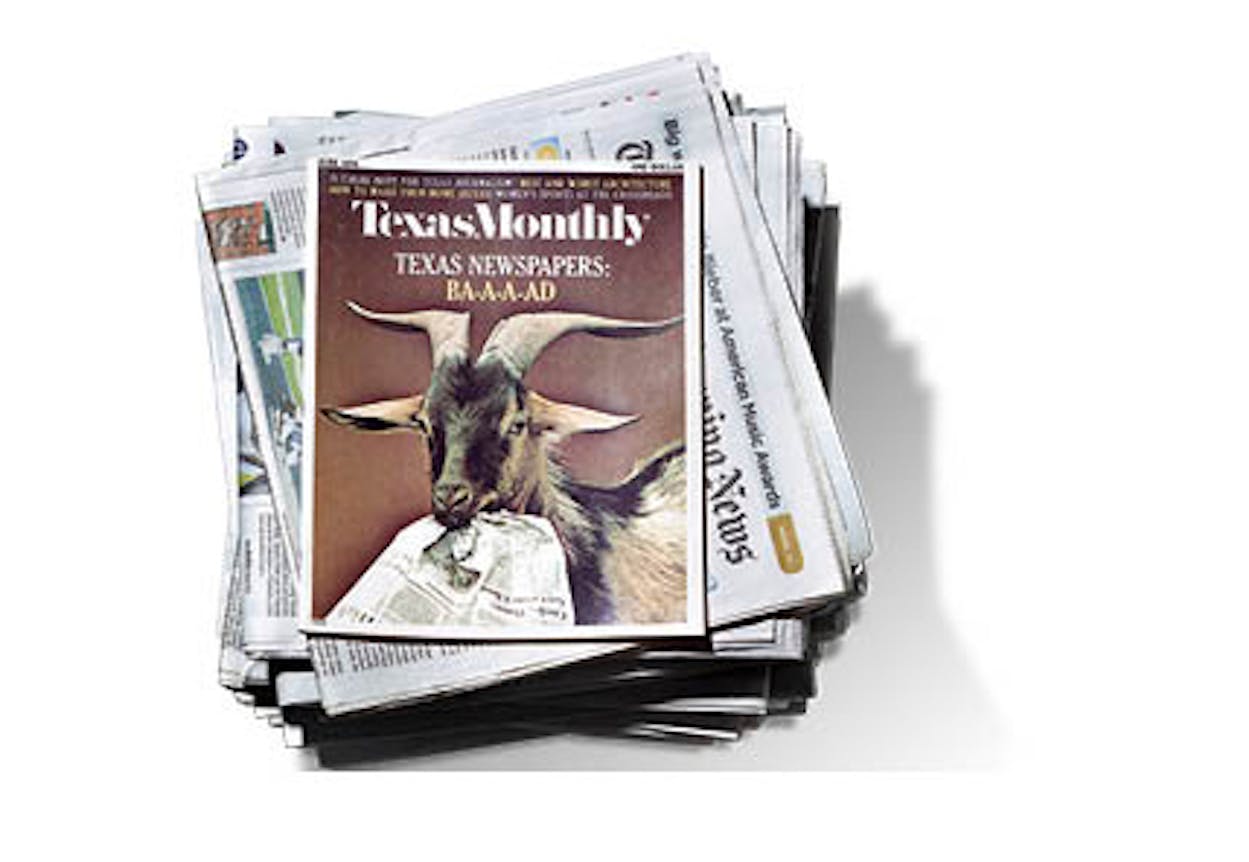

The goat on the cover of the June 1974 issue of this magazine was a nice touch. If you wanted to illustrate the descent of the state’s big-city newspapers into a form of journalistic trash, why not an image of a refuse-eating barnyard animal gobbling up a front page unworthy of wrapping fish? Griffin Smith Jr.’s accompanying story was no more subtle. “Texas journalism is, on the whole, strikingly weak and ineffectual,” he wrote, going on to tar his own profession as a “backwater.”

Wait a minute. The seventies wasn’t a golden era for the news business in Texas? From here it certainly looks like one. Back then two daily papers were published in Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, San Antonio, and El Paso. Today, not counting Spanish-language dailies, there are no two-newspaper markets anywhere in the state. There were more reporters and editors on the staffs of the big-city papers in those days, and they had more experience and more institutional memory than the current crop. And of course, papers were fatter then. More pages meant more of a “news hole.” These days the paper that hits your doorstep isn’t quite as thin as a takeout menu, but it’s not far off.

I’ll admit to having an unsubtle point of view myself. Three and a half years after stepping down as Texas Monthly’s president and editor in chief, this is the universe I’m in: I’m the co-founder of the nonprofit digital news organization the Texas Tribune, which both collaborates and competes with the dailies. So I’m not exactly a disinterested observer. But I’d hardly be the only one to argue that the big-city newspapers, as a group, have gone from “BA-A-A-AD” (as the cover of that June ’74 issue asserted) to worse.

Clearly there are some things that each of the city papers does well. There’s the Dallas Morning News’ robust opinion section and Jim Drew’s investigative reporting (most recently his series of stories on the turmoil at the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas). The El Paso Times’ ongoing coverage of the cheating scandal in the El Paso Independent School District. Terri Langford’s reporting on health and human services for the Houston Chronicle and the San Antonio Express-News. Punchy columns by Bud Kennedy in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and Ken Herman in the Austin American-Statesman.

But the list of less-good things is just as long: the near-disappearance of homegrown business coverage and feature writing at the Statesman. The closing of the Star-Telegram’s venerable Capitol bureau. Several rounds of destabilizing, morale-destroying layoffs at the Morning News, the Chronicle, and the Express-News. And, of late, the revolving door at the top of so many mastheads. Austin, El Paso, Houston, and San Antonio have all changed top editors in the past two years. Austin has had three publishers in the past three years.

The culprit, as has been widely noted, is the collapse of the papers’ traditional three-part revenue model. Classified advertising long ago leaped into the welcoming arms of Craigslist. Display ads for car dealerships, luxury retail, and the like have plummeted thanks to the past decade’s weak economy. And paid circulation took a hit when the papers decided to give their product away online. (The Dallas and Houston papers have lately placed most of their content behind a paywall, but it’s difficult to put the toothpaste back in the tube.)

Debbie Hiott, the editor of the Austin American-Statesman, laments the dwindling resources at her disposal, which have resulted in “a pullback of coverage in some suburban and neighborhood areas that readers have since told us they really miss.” Hiott, who took over the top job in 2011, acknowledges as well that some agencies and governments don’t get covered as much as they once did. But having to do more with less has had an upside, she says. “It has required all the papers to focus the staff we have left more on what really matters to readers and less on our whims as storytellers. We’re doing more of the things that keep newsrooms relevant: watchdog, accountability, investigative journalism.” The Statesman has also been adept at using social media to disseminate headlines and breaking news in the state’s most wired city.

Almost every editor of a Texas newspaper will tell you something very similar—that their papers have grown leaner but more focused. And there’s some truth to that. But this shift has come at a great cost to the communities they serve in at least three ways.

First, city newspapers are no longer able to adequately fulfill their aspiration to be the one true public square—the place where the community comes together to air its points of view, sometimes loudly, on the issues of the day. Fewer papers and fewer pages mean less of an opportunity for festering problems to be uncovered and potential solutions to be illuminated and for people of unlike minds to hash out their differences for the collective good.

Second, the slimmed-down papers are harder-pressed to play their designated explainer/interpreter/arbiter role. The population of Texas has grown from 20 million to more than 25 million in the past 12 years. Something like 1,000 people move to Texas every day. Many of those folks are settling in the big cities, and yet they know nothing about the culture and the history of their new homes; for them, Dallas and Houston and Austin may as well be Denver and Charlotte and Atlanta. They need to know, at a minimum, the basics about urban life—where to go, what to do, who the players are, which traditions will one day seem familiar. They’re not getting enough of that in today’s papers.

Finally, the decline of the newspaper business has robbed big-city residents of one of the last remaining shared experiences. Many of us walk around with headphones in our ears to keep the world at bay. We carefully curate our Twitter feeds to reinforce our existing worldviews, and we can barely stomach talking to people we disagree with. We’ve exiled ourselves into pods, and the likelihood of having anything in common with our crosstown neighbors has significantly diminished. Reading the morning paper was once a rare connection with the people to your left and right, directionally and otherwise. No more.

Some will surely argue that the good old days of Texas journalism weren’t really that good—that the quality and ambition of the papers published at the time of Griffin’s piece have been romanticized when set against the hot mess of today’s news business. But whatever you think about the way things were, the way things are isn’t serving the cities terribly well.

Still, if the papers figure out how to get their balance sheets in balance, the current environment offers them a chance to connect better with our cities. Jim Witt, the executive editor of the Star-Telegram since 1996, talked about the wider reach of the newspaper in a time of tweets, blogs, social media platforms, and the like. “More people see and react to our content than ever before,” he says. “It’s no longer a one-way lecture; it can be a real conversation. Those dang readers used to trust everything we said. Now they want to inject their opinions into the mix and question us and tell us how wrong we are most of the time.”

The technology that has been so disruptive to the economic and content models of many papers is pointing the way to a new era of, yes, quality and ambition. And innovation as well—the various platforms and channels may finally give big-city dailies the means to meet those ossifying public obligations. It’s overdue. The editors and reporters know it, and the smart owners know it too. Those who don’t, who fail to acknowledge reality, are the real goats of this story.

- More About:

- Texas History