They Want My Soul is Spoon’s eighth record. And there’s perhaps no lousier time to write about a band than eight records into its career. By that point, the band’s backstory—the initial gathering of the members, the early feuds and struggles, the big break that may or may not have led to a big payday—has been told countless times. Barring a dramatic breakup and reunion or a rare Black Keys–style late-career jackpot, a band putting out its eighth record is usually going about its business, playing to an aging fan base that doesn’t expect anything else. Spoon is not that band. In fact, Spoon is so much not that band that there are two big story lines swirling around They Want My Soul. The first has to do with the unusual number of years Spoon fans have been waiting for it. Since 1996, the Austin rock group has put out a new album every two years or so; They Want My Soul arrives after an unprecedented four years. The second story line is a bit more inside-baseball, though Spoon’s impassioned, slightly nerdy fan base is precisely the sort that pays attention to that kind of thing: after a brief and disastrous six-month stint on a major label, Elektra, in the late nineties and a decade-long, career-making stint on the independent label Merge, Spoon has returned to the majors in hopes of a big marketing push; They Want My Soul is being released by Loma Vista, a subsidiary of Universal Music.

And yet, when front man Britt Daniel and I meet in June for Saturday brunch at East Austin’s Mi Madre’s, he says he’s already weary of both of those story lines—even though this is the first interview he’s done for the new album. Sure, the three years that the members of Spoon spent pursuing other projects could imply a troubling restlessness among the bandmates. And the move to a major label means that Spoon might experience one of those rare late-career jackpots. But Daniel has a different story in mind.

“Our sound—this indefinable thing—should be the point of your piece,” he offers. Not that he’s all that interested in talking about the band’s sound himself. When I ask what makes a Spoon song so instantly identifiable, I get very little back, even though I pose the question in slightly different ways four or five times.

“You want some great quote where I just lay out the ingredients?”

Yes. That would work.

“Indefinable,” he says, suggesting we move on.

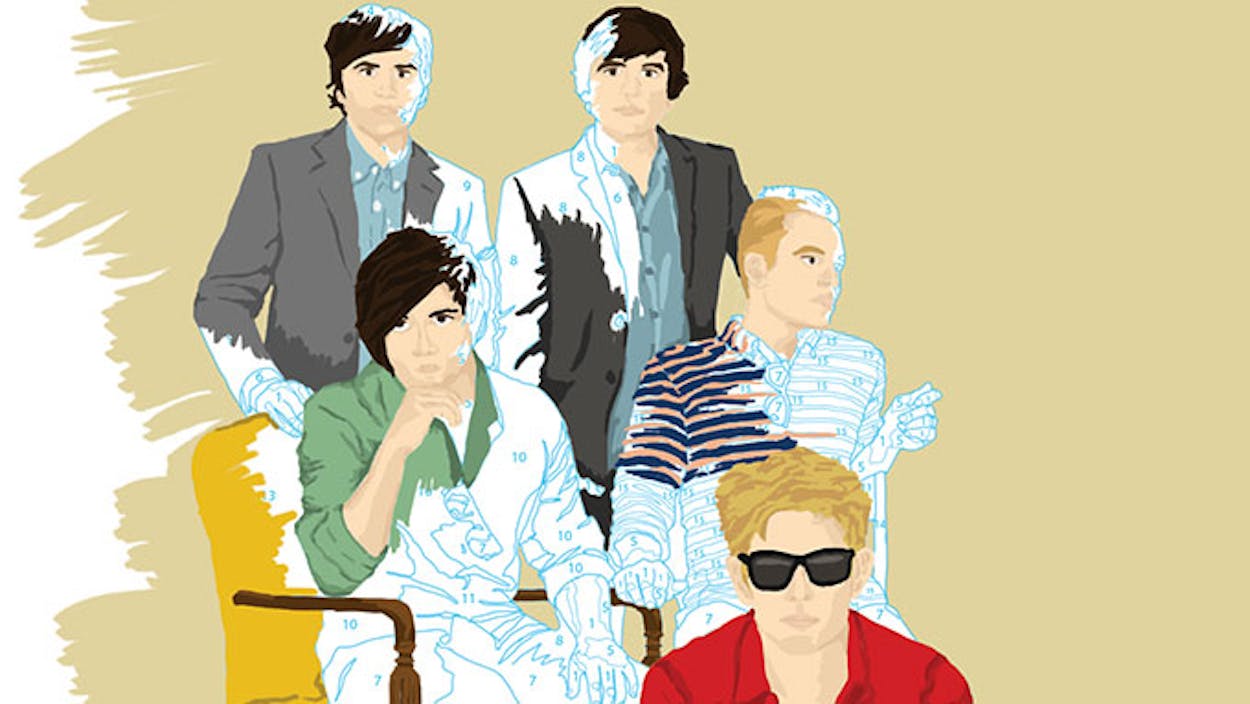

Not a chance. Spoon’s sound has always been tough to describe. But twenty years and eight records in, Spoon is so confident, so unwavering in its commitment to a sound, that They Want My Soul pulls off the neat trick of sounding a lot like pretty much every other Spoon album while also sounding better than pretty much every other Spoon album. A half-dozen tunes on the record are easy to peg as Spoon songs during the first ten or fifteen seconds, even before Daniel’s voice enters. And that’s not a complaint; They Want My Soul works because of, not in spite of, the fact that it sounds so much like a paint-by-numbers Spoon album.

“Paint by numbers,” not surprisingly, is a modifier Daniel doesn’t like. “I wish there was a black-and-white outline and they told me which paints went where,” he says with a dash of snarl. “That would be a lot easier, a lot less intense, than actually making a record.”

Spoon started They Want My Soul last September in Austin with producer Joe Chiccarelli (the Strokes, the Killers, My Morning Jacket) and recorded a handful of songs by November. Then, in mid-January, after Daniel had written a few more songs, the band finished the album with Flaming Lips producer Dave Fridmann, in his New York studio. Switching producers halfway through a project isn’t usually a good sign—the band wound up scrapping a few of the songs it had recorded with Chiccarelli—but Daniel says that he was happy doing things at his own pace. For a long time, he says, he had worked too quickly to enjoy the process. That’s why, three years ago, he gathered bandmates Jim Eno, Rob Pope, and Eric Harvey to say he wanted to put Spoon on hiatus. “It was write, record, tour, repeat for too long,” says Daniel. “I just needed to do something else.”

That something else was Divine Fits, a collaboration with Canadian musician Dan Boeckner that put out its first album two years ago and started off touring small clubs much like any other rookie band. But what appeared to be a step backward for Daniel business-wise was just what he was looking for creatively. By teaming up with Boeckner, Daniel took the pressure of writing all the songs and leading a band off himself. “I always admired the Clash, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones—bands where there are partners who are writing and performing at the same level,” he says. “Being onstage without necessarily having to sing wasn’t something I wanted to do all the time, but it was something I wanted to experience.”

To hear Daniel say he was seeking a partner is a little odd; conventional wisdom suggests that Spoon has always been an intimate partnership between Daniel and drummer Eno. The pair are the band’s sole original members and share production credits on all of Spoon’s recordings. While neither Daniel nor Eno takes exclusive credit for the architecture of the band’s sound, Eno is the barometer of what is and isn’t a Spoon song. “I can immediately tell whether a song is good or bad based on his reaction,” Daniel says. “He’s the go-to.”

Eno, as luck would have it, is also the go-to for describing Spoon’s sound. As reluctant as Daniel is to define it, Eno is eager to do so. “We’ll nerd out,” he said as we were scheduling our interview, hinting at lots of talk about mike placement, panning, and frequency ranges. The first thing he emphasized when we sat down was his drumming—or, more precisely, how he mikes and mixes his drums. “Think about ‘When the Levee Breaks’ or ‘Kashmir,’ ” Eno says, referencing two Led Zeppelin songs known for their epic drum sound. “We’re the opposite of that.” He prefers a snappy, tightly wound strike.

Spoon’s biggest distinction, Eno contends, is its minimalism. Although the band has integrated splashes of horns and a kitchen sink’s worth of synthesized sounds into its music over the years, its hallmark is not how many but how few instruments are in the final mix. “We tend to throw a lot of ideas at a song and then strip it all away,” he says. “What you’re left with is pinpointed accuracy. You can actually make a song that has space in it sound bigger than a song with a ton of instruments. When you keep laying guitars down, the sound actually gets smaller because you’re eating up more of the frequencies. Once you say there’s going to be only one guitar, bass, keyboard, and drums, things are suddenly wider from left to right, and then the low and high have room too.”

What keeps all of this from devolving into a formula—or, as one insensitive writer might put it, paint by numbers—is Daniel. More specifically, Daniel’s singing. On They Want My Soul’s opener, “Rent I Pay,” Daniel’s delivery—the way he breaks syllables at unexpected points, his throat-clearing growl, the way you can almost hear his spit hitting the microphone’s casing—is perfectly bombastic. Yet just a track later, on “Inside Out,” he’s slowly teasing out words, riding on top of a taut, Portishead-style groove. “Sometimes you can get your point across not in what the words mean but in the way they sound,” Daniel says. “That’s what I find interesting.”

The album’s centerpiece and first official radio single, “Do You,” is Spoon’s sparkliest, most obvious pop song since 2003’s “The Way We Get By.” But it’s not a simple pop song by any means. A Beatles-esque series of do, do, do, do, do’s introduces a quick verse, followed by a catchy chorus that asks a series of questions that begin with the words “Do you” (“Do you want to get understood?” “Do you feel in black and blue?” “Do you run when it’s just getting good?”). Then, when you think you’ve grasped the full measure of the song’s hookiness, the wordless intro returns as a secondary chorus. It’s not, perhaps, as surefire a “song of the summer” candidate as Pharrell Williams’s “Happy” or Ed Sheeran’s “Sing,” but it wouldn’t sound out of place between them on the radio. Daniel bristles when I call it “blatantly commercial,” as if it’s an accusation, but Eno doesn’t seem offended.

“If you deconstruct ‘Do You,’ there’s probably five distinct vocal hooks,” he explains. “It’s a three-and-a-half-minute pop song crammed with hooks—the chorus, the verse parts, all the harmonies. There’s gold in there.”

Whether Universal’s two-year-old Loma Vista imprint can mine that gold and turn “Do You” into a radio hit more effectively than Merge would have remains to be seen. “They have a bigger infrastructure,” Daniel says. “More money [to push the record]. More people plugging the song to radio. We’re grateful for what we have, but we also have ambitions. I feel like the record we made could appeal to a lot of people. I’d like to try to make that happen.”

The problem, of course, is that a lot has transpired in the music industry during the four years Spoon has been out of the picture. Album sales, which took a big hit fourteen years ago with the advent of iTunes and other single-song digital purchasing platforms, have recently taken another dive as people have latched on to streaming services like Pandora and Google Play. In 2010 the band’s previous album, Transference, sold 53,000 copies its first week and debuted at number four on the Billboard chart. Will They Want My Soul sell less because people will just listen to it on Spotify? Or will it sell more because Spoon’s hiatus has built demand and Loma Vista has the marketing muscle to take advantage of that? No one really knows. And it’s certainly possible that the shifts in the industry will work in the band’s favor. Superstars don’t rack up the numbers they used to, but moderately successful bands that do something well for a long time seem to be able to get their fans to shell out for albums. As the big fish get smaller, the little fish suddenly loom a bit larger.

Sometimes that sort of year-in, year-out consistency boils over. It’s how bands like Phoenix and the National turned themselves into bona fide stars after years of working on the margins of the industry. Spoon has been nothing if not consistent; the phrase “sounds like Spoon” means something. Unless there’s a late entry to the August 5 release schedule from a bigger-name band, Spoon could move 53,000 units like it did the last time around and this time, find itself at the top of the charts. And it couldn’t happen to a more deserving bunch of guys. Just ask Britt Daniel.

“It’s extraordinary for a band to be putting out records this good twenty years in,” he says. “Who else is making the best records they’ve made—or flat out really good records—at this point in their career? It’s rare. We make good records. I know that. Without reservations.”

- More About:

- Music

- Britt Daniel