This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Johnny Chan looked at me directly and said, “I am the most aggressive poker player in the world.” He said this without a hint of irony or embarrassment. He was not kidding. At the same time, his boast had all the elements that characterize his style at a poker table. It was bold and uncompromising; it was supremely confident; and, although possibly not true, it would be as difficult and expensive to expose as one of his wicked bluffs. Here is a man who once lost a $1.2 million pot and, unfazed, proceeded to win all that back plus all the rest of his opponent’s money in a little over an hour.

At 31, this graduate of Lamar High School in Houston is now the most dominant poker player in the game. In 1987, triumphing over a field of 151, Chan won the famous World Series of Poker, sponsored by Binion’s Horseshoe Casino in Las Vegas. There are many poker tournaments, but this grueling four-day affair is the oldest and most prestigious. He won the World Series again in 1988 against 166 other players and capped off the year in December by winning Binion’s Hall of Fame poker tournament. He is the leading money winner in the World Series, having finished in the money five times for a total of $1,554,000 in winnings. This May he will be competing for his third straight title. Although two other players have won the tournament twice in a row—Doyle Brunson in 1976 and 1977 and Stu Ungar in 1980 and 1981—no one has ever won it three times in a row. Each year the tournament grows larger and more difficult. Yet Chan fully expects the winner this year to be himself.

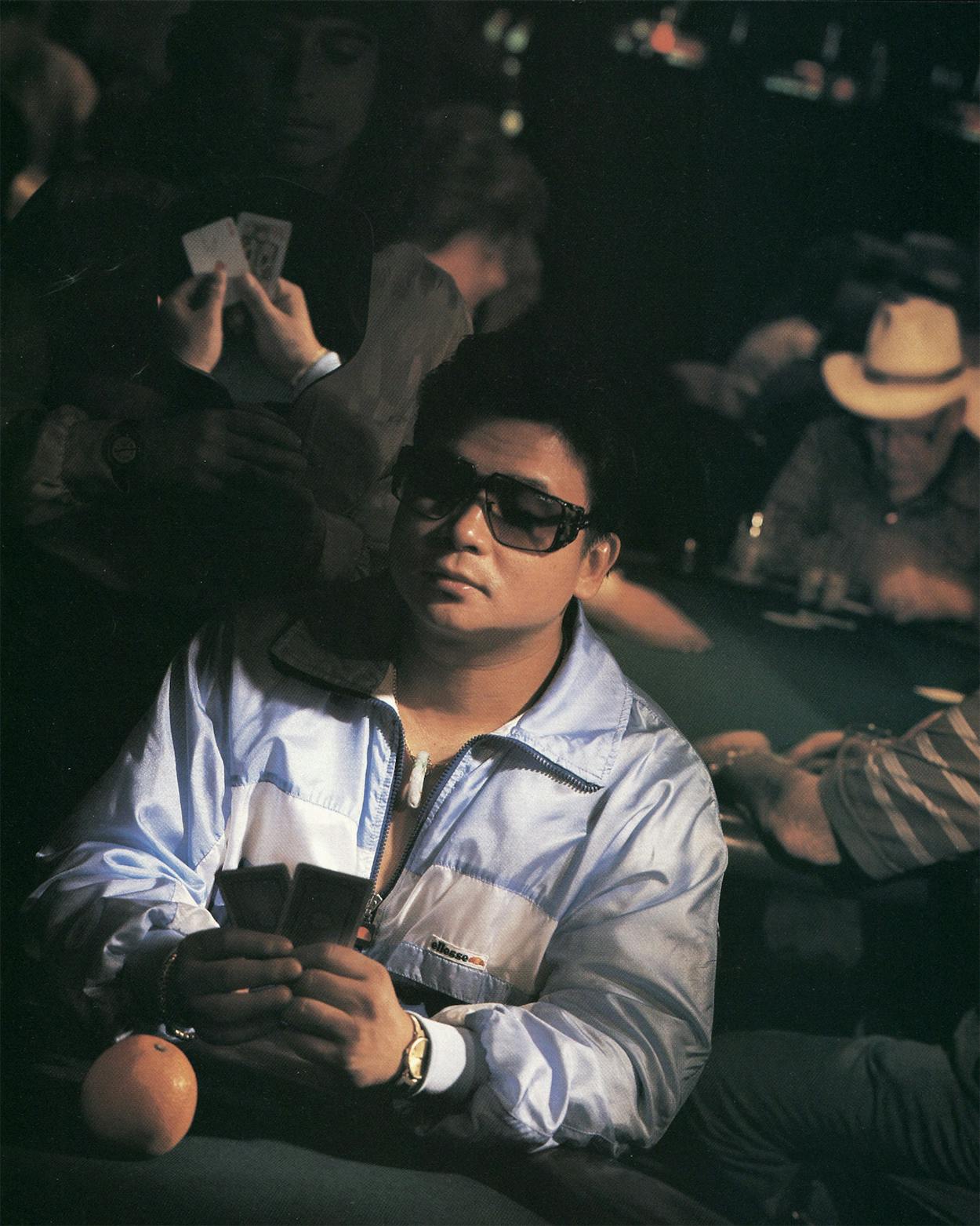

He is successful because of his talent and experience and because he is not tempted by the traditional failings of gamblers. He is a family man with two young children. He has houses in both Houston and Las Vegas and an apartment in Los Angeles. He travels frequently with his family in the United States and the Orient. He has a job as a consultant for the Sycuan Gaming Center, the largest card room in the San Diego area. He neither smokes nor drinks, and he keeps to a regular regimen of jogging and weight-lifting. When playing poker, he frequently keeps an orange on the table by his chips. He scores the peel and wafts the scent to his nostrils to combat the smell of smoke.

He moves with great agility and uncommon purpose, walking so fast at times that I had to hurry to keep up with him. He is short but solidly built with a barrel chest and sloping shoulders. He has a round face and round cheeks and a short, thick neck. While guarded and even somewhat thorny, he treated me with a consistent courtesy and thoughtfulness that made me think well of him. Still, he is clearly a man to be reckoned with. Even while patiently answering questions or sitting at the poker table, he is so charged that he projects an impatience powerful enough to be daunting.

Except for his wife and children, he seems interested only in betting on sports, speculating on the stock market, and playing poker. Frank Henderson of Houston, who finished second to Chan in the 1987 World Series, says, “He has all the things a poker player has to have—confidence, good physical and mental condition, aggressiveness, patience, and money.” Erik Seidel, who finished second to Chan in the 1988 World Series, says, “He is capable of making terrific plays by reading players very well. A play you might make against others you might not try against him, because he could pick up on it. He is the best psychologist at the poker table, and he has heart. He isn’t afraid to bet a lot of chips without having anything.”

Things were very different twelve years ago, when Johnny Chan first came to Las Vegas for a vacation. He was not entirely inexperienced at gambling—he had learned to play poker in nickel-and-dime games while he was studying hotel management at the University of Houston. He could play pool well enough to pick up some money hustling. In all other respects he was typical of many young men who come to Las Vegas looking for excitement and find more than they can handle. Born in Canton in Mainland China, he came to the United States in 1968 with his family. His grandfather had lived in Houston since 1945 and had finally arranged for his relatives to join him. Chan’s father settled in the middle-class area near Shepherd and Alabama and successfully ran restaurants.

That first trip Chan jumped into an orgy of craps, roulette, blackjack, and slot machines. He lost all his money except $200. With a what-the-hell attitude, he sat down at a poker table at the Golden Nugget. He started out in a $20 limit game and soon graduated to larger ones. The level of play was better than in Houston, but Chan had luck on his side. In a week he built his $200 into $20,000 and was convinced he had found his life’s calling. Then at the Golden Nugget he met a cagey Texas gambler named E.W. who suggested he and Chan play one on one, or “head up.” E.W. won all of Chan’s money. In the end he loaned Chan $500 so he could get back home. At the time the experience was devastating, but now Chan thinks of it as the event that enabled him to rise above the pack of other poker players: “That money was an investment, an investment I had to make to accomplish what I have. That was where I learned to play head up. In the last two tournaments, when it came down to the end with just me and another guy, I won because I had the experience. How often do people play head-up poker? Almost never. But I had. I had seen somebody clean me out playing head up.”

In Houston he worked for his father, but he continued to go back to Las Vegas. When he played poker, he lost: “I was terrible. People used to be happy to see me show up. ‘Come over here, Johnny,’ they’d say. ‘Sit down and play.’ And they would brush off a seat for me. Many times I had to go to pawnshops and hock all my jewelry. I ran up my credit cards. I would get some money from home. Nowadays I tell people you have to be a sucker before you can be a winner. I was a sucker for a long time.”

“At first a lot of players looked down at me when I would go home broke. Now they come to me for answers.”

One day he woke up broke without any prospects for getting more money. He accepted the obvious solution to his problem and got a job. For six months he worked as a cook at the Fremont Hotel in Las Vegas. Saving his money, he didn’t play any poker at all until he had built up something of a bankroll. When he began playing again, he won. During his brief retreat from the poker tables he had finally come to understand what was keeping him from winning.

He had not been playing to win; he had just been playing. Such purposelessness is the most common failing of all losing gamblers. At first gambling can produce a pleasurable rush of tension. If one wins early, the result can be an intoxicating elation. But continued gambling is tedium itself. The dice roll, the wheel spins, the cards are dealt over and over and over again. Soon most people at a casino, particularly those around a poker table, are lulled by the tedium into lethargy. They look at their cards. If they have a good hand, they bet. If they don’t, they fold and wait like automatons for the next hand to be dealt. They are not really playing but simply passing time by going through motions involving cards and chips. The more one plays, the more narcotic the constant repetition can be. A player so anesthetized can never win. Thus a poker player must learn to stay alert and concentrated on the events at the table hand after hand, hour after hour, day after day. Chan says, “A lot of players don’t have a goal. When I was playing to be playing, I didn’t care if I went broke. The next day I could always call Dad. I had to learn when to quit. I set a goal to win or lose between two hundred and four hundred dollars a day. I would quit when I reached my limit. And every time you walk away a winner, you feel better and you sleep better. You have a feeling of winning.” He sticks by that system today, though his goals have changed. He wants to win $10,000 now. When he gets that far ahead, he plays until he loses a hand. Then he quits. (It’s interesting to estimate his income from this information. If he plays two hundred days out of a year and wins his limit only 60 percent of the time, he wins $1.2 million. The 40 percent of the time he loses costs him $800,000, leaving a $400,000-a-year profit. But this may well be too low. Rumors about Chan’s wealth abound in Las Vegas.)

Chan will play any variety of poker, but the most common at his level are seven-card stud and hold ’em. The latter, sometimes called Texas hold ’em, is the game played at Binion’s World Series and at most of the other tournaments. Each player is dealt two cards face down after which there is a round of betting. Then three cards are dealt face up in the center of the table. This is called the flop. These three cards are communal; each player uses them in combination with his two face-down cards to make a hand. After the flop there is another round of betting. Then another card is dealt face up in the center of the table. It’s called fourth street. There is another round of betting. A fifth card—fifth street—is dealt in the middle of the table, and there is a final round of betting. At the end each player can use seven cards—his two face-down cards and the five face-up cards in the middle of the table—to make his hand. The combination of exposed and concealed cards and the four rounds of betting make hold ’em a game of intricate strategies and large pots, both reasons for its becoming the game of choice among those whom the publicity from Binion’s likes to call “poker professionals.”

Hold ’em’s dominance has helped create a style of play that is entirely different from the game described by most books on poker. They usually recommend folding if you don’t have a certain minimum holding, say a pair. Better hands are worth a raise, still better worth a reraise, and so on. The theory is that folding early loses only the ante; betting weak hands would lose more. Chan is contemptuous of these authors: “I’ve played with people who write books. They play ABC poker. They look for a pair or an ace, and if they don’t have it, they throw their hands away. You can always tell what they have.” Instead Chan—the most aggressive player in the world—likes to “put a lot of gamble into a lot of pots. When I was playing in the little games I made wild plays, but then I did what nobody had done, which is make wild plays in really big games. At first a lot of players looked down at me when I would always go home broke. Now they come to me for answers.” He grins and shrugs. “I tell them I made a lucky guess.” The point of his aggressiveness is not to win a few big pots, as books recommend, but many pots of whatever size. Modern top poker players are greedy even for the antes.

Nothing illustrates Chan’s style better than the final hand of the 1987 World Series. His last opponent was Frank Henderson, who, before he began playing poker full time, used to run the scoreboard at the Astrodome. Henderson had about $300,000 in chips while Chan had almost $1.2 million, four times as much as Henderson. In any game, but particularly in a head-up game, the player with the most money has an advantage. After the first two cards, Chan bet $60,000. Henderson held two 4’s. He pushed all his chips into the pot, a raise of $240,000. Chan called the raise. Since there could be no more betting with all of Henderson’s chips in the pot, the two players turned their cards over before the flop. Henderson was surprised to see that Chan held only an ace and 9. The flop helped neither player, nor did fourth street, but on fifth street Chan caught a 9, giving him a higher pair than Henderson’s 4’s and the championship. If Chan had lost the hand, he still would have had a big lead in chips. As it was, he had a chance to draw out and win, he took it, and he got lucky. It sounds unscientific compared with the conservative approach advocated in books, but that is the style of Chan and the other leading modern players. Actually, thinking of them as poker players is subtly misleading. Poker is a game of skill, but it still contains large elements of risk. Ask Johnny Chan what he is, and he will say, “I am a gambler.”

Chan’s aggressiveness is a weapon, but it is not a club that he swings indiscriminantly. “When I sit down at a table I usually know who the strongest players are, so I leave them alone. They aren’t going to lose a lot of money. I pick on the weakest players. I like to sit in front of them [that is, at their right] so that I act before they do. If I check [pass], they think that means take it, so they bet. Then I am able to act after them, and if I have a hand, I can raise.” Chan sits quietly at the table, but his hope is that something—a lucky draw to win a pot, for instance—will put one of the other players “on tilt,” so angry that he wants revenge. “I’m looking for somebody to throw money at me; then I can take a stand. You put on your aggressive show. Then they think you never have anything when you bet. They are going to call you no matter what. Then you put your aggressiveness in park and come back when you have a hand.”

Chan’s victory over Erik Seidel in last year’s World Series was a masterpiece of control. Seidel was a newcomer to the tournament who stunned everyone by getting to the final two with Chan. He is a tall, thin, gawky man of 29 with a narrow face and light curly hair. An option trader in New York until Black Monday threw him out on the street, Seidel began playing poker more seriously and found, almost to his surprise, that he had a natural affinity for the game. He was an audacious player during the tournament.

When he and Chan began playing head up, Seidel had considerably more money than Chan. Chan made a private offer to Seidel. First-prize money was $700,000 while second was only $280,000. Chan proposed that Seidel give him $120,000 to reduce the gap between the two prizes. Then, no matter which way they finished in the tournament, Seidel would get $580,000 and Chan $400,000. Seidel said he wanted to win; Chan said he didn’t care about that as much as the money. “Aggressive” is perhaps not an adequate word to describe this offer. Chan, the underdog, wanted to be paid by the leading player. Seidel refused. All the logic and probabilities of his position said he was right to refuse, but all the logic and probabilities were wrong.

As they played, Chan won enough hands to actually take the lead in chips. But soon afterward Seidel caught a pair of 9’s on the deal and bet all his money, $600,000. Chan called the bet. He had a pair of 8’s. The cards turned up in the middle of the table helped neither player. That meant Seidel’s 9’s were good for the largest pot in the history of the World Series—$1.2 million. Chan was left with only $470,000, putting him at a three-to-one disadvantage.

After the record pot, the tournament officials called a brief time-out. Chan went outside for a short run to clear his head and decide how to proceed: “I thought that if I hadn’t played that big pot, I would still have about as much money as he had. I decided not to play any more big pots.”

At that point in the tournament, an advantage in chips is even more powerful than usual. The rules are that in addition to antes of $2,000, the nondealer must bet $10,000 blind (that is, before the deal) and the dealer must bet $20,000 blind. Under these conditions a player who folds four hands in a row loses $60,000 plus four antes for a total of $68,000. Thus, the player who is behind in chips cannot wait for good hands. If he folds repeatedly, the antes and the blinds will drain away all his money. Instead he must play his cards whatever they are and create whatever opportunities he can. That is just what Chan did in one small hand after another. “When you play head up,” he says, “you train your opponent to do what you want. If I check, you are supposed to bet. If I bet, you are supposed to fold. If I call, you are supposed to bet again the next round. Since I didn’t want any big pots, when he checked, instead of betting $100,000, I bet $40,000, and pretty soon he was betting that too. It would be hard for me to call $100,000, so I got him thinking that $40,000 was the right size bet. Whatever I did he would think was right.”

Chan lost some hands until he was down to $270,000 to Seidel’s $1.4 million. But after that he won repeatedly in a brilliant display of courage and ingenuity until he had evened the chips between them. “In the beginning I felt I was okay and could play well head up,” Seidel recalls. “But it turns out I was wrong. After winning the big hand and he started coming back, there was a point when I thought I’m not sure I can really beat this guy. I started thinking it was going to be difficult, and I was getting tired. It was the same for him too, but he would be better in that circumstance than I was.”

Chan was considerably better. By the final hand of the tournament Seidel was completely in Chan’s grasp. Chan’s last two cards were the jack and 9 of clubs. Seidel held the queen of clubs and the 7 of hearts. Chan opened with a small bet, and Seidel called. The flop was the queen of spades, 8 of diamonds, and 10 of hearts, giving Chan a straight. No higher straight was possible at this point, nor could Seidel have a flush. The most he could have was three of a kind—a pair down that matched one of the up cards—but even that was unlikely since Seidel probably would have raised before the flop if he had been dealt a pair. Assuming Seidel didn’t have a pair down, there was still the remote possibility that he could draw a straight, a flush, or even a full house with the final two cards. Otherwise Chan had a lock.

It was Chan’s bet. He threw out a lure, betting his training unit, $40,000. Seidel had a pair of queens, after all, which looked very powerful to him. Without hesitation, he raised $50,000.

Here, with an opponent raising right into a powerhouse hand, is where even an expert poker player might not be able to resist a massive reraise and a satisfied grin. Instead Chan lured Seidel even further into his trap with a display that for power of conception, mental and physical control, and absolute singleness of purpose has seldom been equaled in any sport or game. Chan stared for several seconds at the chips in the pot and chewed his gum. His face, partially hidden behind dark glasses, betrayed no emotion whatsoever. Then he began toying with a small pile of chips with his left hand. He put his right elbow on the table and rested his head in his palm. Then he took another look at his hole cards. He made a tent over them with his fingers and turned up the corners slightly with his thumbs. He studied them for a second. Then he toyed with his chips again and rested his head in his hand. He counted $50,000 in chips and set them at the side of his stack. Finally, he tossed those chips in the pot.

The fourth card turned up was the 2 of spades. It was Seidel’s bet. He checked. A normal poker player in Chan’s position would bet his strength here. Chan shifted in his chair and stared at the four cards in the center of the table. Then he sat back and rolled his eyes toward the ceiling and let out a deep breath. He checked.

The fifth card was the 6 of diamonds. Now even the remote possibilities for Seidel to win were exhausted. There could be no full house or flush for him. He could not beat Chan’s straight. But Seidel still had his two queens, and nothing in Chan’s betting or demeanor had indicated any strength. The only clue was Chan’s calling that $50,000 raise. Seidel said later that he thought there was something “smelly” about the hand. Maybe so, but at the time he didn’t catch a scent strong enough to save him. He looked at the cards on the table for a second before confidently shoving all of his remaining chips into the pot. Chan immediately jumped to his feet and in one motion threw down his cards and put his own chips in. He had won again. He stepped back from the table and raised both arms in the air. “He was playing so fast and trying to bluff his money off,” Chan said just after the hand. “So I sat back and lay a trap for him. And sure enough, he tries to bluff all his money off on me.”

One night late last March Johnny Chan, the greatest poker player in the world, had two pairs, 9’s and 7’s. He was playing seven-card stud in a game at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. The ante was $25, but the maximum bet was only $200, smaller stakes than he likes to play. Otherwise this was a typical night in the life of a poker player. Everyone else had dropped out of the hand except for a plump man of about thirty who was sitting on Chan’s right. He had a queen and a jack and a 9 showing. Chan bet $200, and the man called.

It was one o’clock in the morning. Chan had arrived in his Mercedes about thirty minutes before, using a plastic card to enter a small private lot at a side entrance to the casino. He was wearing a blue Fila sweatsuit, a gold watch set into a gold bracelet on one wrist, a gold bracelet on the other, and a gold necklace with a carved jade charm.

In the poker room quiet groups were playing at six or eight tables. The big-money game was at a table in the back, farthest from the entrance. When Chan arrived, the game was dwindling, but a few players sat down to play stud, and a group of six to eight men came in and out of the game. Some were sharp-looking young men, but a few were so ratty they could have been derelicts. From their pockets they pulled thick wads of $100 bills wrapped in rubber bands. They put their money behind their piles of chips. Each player had at least $10,000 in front of him; several had considerably more. Beside an Asian man in his forties sat an extremely beautiful young woman in an off-the-shoulder black dress. She watched quietly, looking almost like a privileged college student at a lecture. Then she would tilt her head so her long, dark hair hung straight down while the gambler stroked it passionately.

Chan was bored with the game. He had won several thousand with a flush almost as soon as he sat down, but since then the slow pace clearly taxed his patience. Players would casually toss $100 bills into the pot and gossip about who had won and lost big hands earlier that night. Chan sat out as many hands as he played. For him, the action was just too slow. As he played the two pairs, he put in his money without apparent interest. The final card and bets came, and the two players exposed their cards. The plump man had filled a straight with his last card to win the pot. “What can you do about that?” Chan said under his breath.

A handsome man in a gray-silk jacket showed up. Everyone wanted him to play. “I don’t play anymore,” he said. “I’m a businessman now. I’m a land developer.” Pretty soon he and two other players, both sharp young men, were talking about going to a disco named the Shark Club for a drink. They asked Chan to come along. “That game was too boring for me,” he said as he walked out. “If I don’t feel right, there’s no point in playing. There’s always tomorrow.”

In the private parking lot he admired a new Jaguar that belonged to one of the other gamblers. Then he put his own immaculate blue Mercedes in gear. He flipped on a tape of mellow rock and took a stick of sugarless gum from a large pack on the console. The seats had deep cushions and long, curved backs. The car smelled pleasantly of pine from a tiny air freshener hanging on the rearview mirror. An arm with the seat belt came automatically out from behind the seats. Chan ignored it and drove off toward Shark’s.

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston