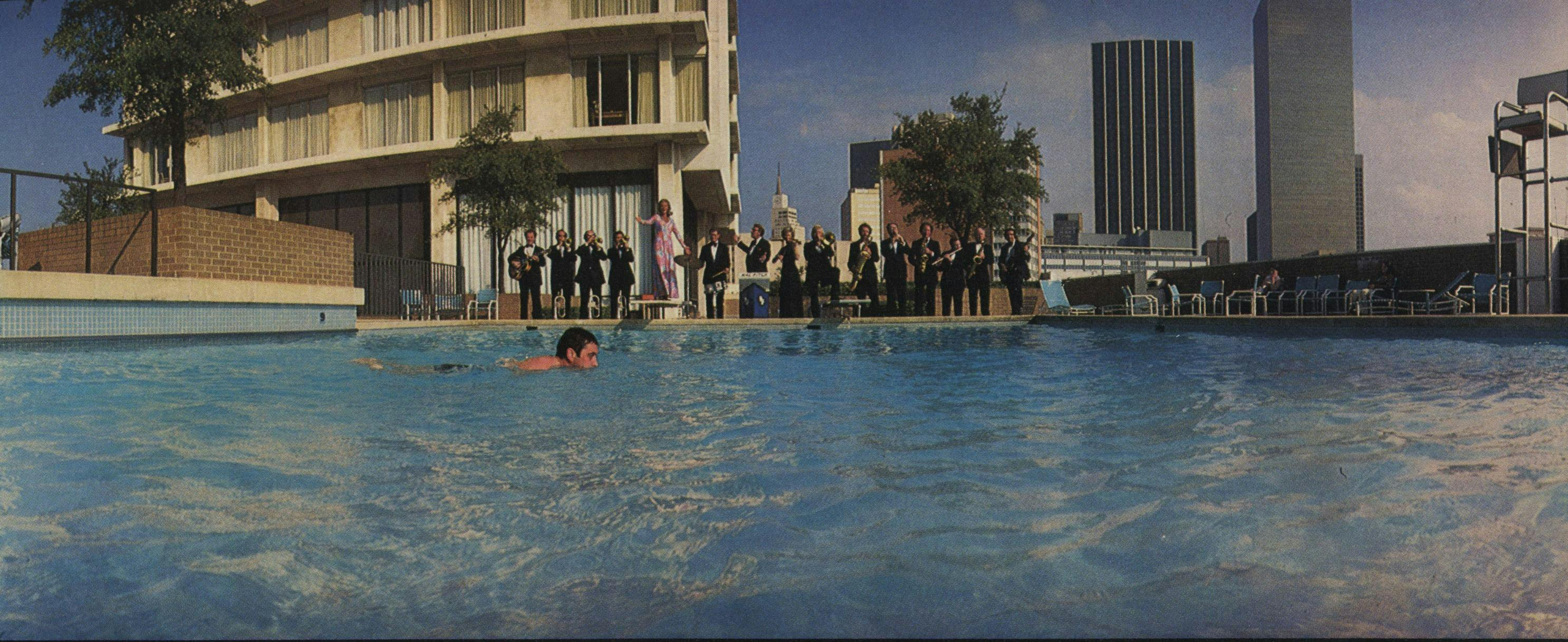

For every type of savage breast there is a special kind of music in Texas that will soothe it. The state is seething with ethnic groups of all descriptions, each with its own Texas-influenced brand of music. Norteño music, for instance, isn’t purely a Mexican import; it’s a Tex-Mex blend. And the polkas recorded in our Czechoslovakian communities have been exported to faraway Chicago and Boston where they are known as “Tex-Czech.”

Why Texas should be home to an unusually large number of ethnic hybrid musics and how they have managed to survive intact are matters of some speculation. For one thing, our geographic location allows for wide ethnic diversity. As a Southern state, we share large Cajun and black populations. Mexico is in our backyard. Oklahoma and the Southwest perpetuate our Western frontier heritage. And for another, Texas has always encouraged individuality. But, while it has tolerated and even nurtured certain ethnic groups, others have persevered only because they have been rurally or socially isolated.

In the nineteenth century, Germans, Czechs, Poles, and Scandinavians came to colonize the Texas frontier. The state’s modern drawing card, however, has been its urban centers, which have attracted working people since the industrial years following World War II. Cities like Houston, divided into wards and neighborhoods, have reinforced the cohesiveness of the ethnic groups that have settled there. Even the Anglo neighborhoods resist cultural dilution. Ethnic groups aren’t necessarily minorities.

Texans have maintained their musical differences as much by their feet as with their ears. Ethnic music is dancing music, and the state bulges with roadhouses, dance halls, and honky-tonks, which cater to dancing fools of all persuasions. A good ethnic band makes the Czech want to polka, the Cajun long for a la-la dance, and the stone-faced West Texan rancher break into a cotton-eyed Joe.

But these musics are fragile. They are subject to the homogenization of mass media—of Top 40 charts, Soul Train, and Muzak. In fact, the survival of these enclaves of music depends in large part on the force of the performer’s personality. If the son of Allen Thibodeaux, for instance, wanted to add more pop music to his Cajun repertoire, who would make him play “Jole Blon” when his dad is gone? If it’s not in the soul, the tastes of the audience will have to keep him on a straight and narrow Cajun path.

WE haven’t shown you all the ethnic musics to be heard in this state. We don’t have Sacred Harp singers from East Texas, Tigua Indians from El Paso, German oom-pah bands, Greek basouki bands, or Houston’s unique Zydeco music.

Now that you’ve seen them, why not go hear them? To find them, just keep your ears open. The music is everywhere.

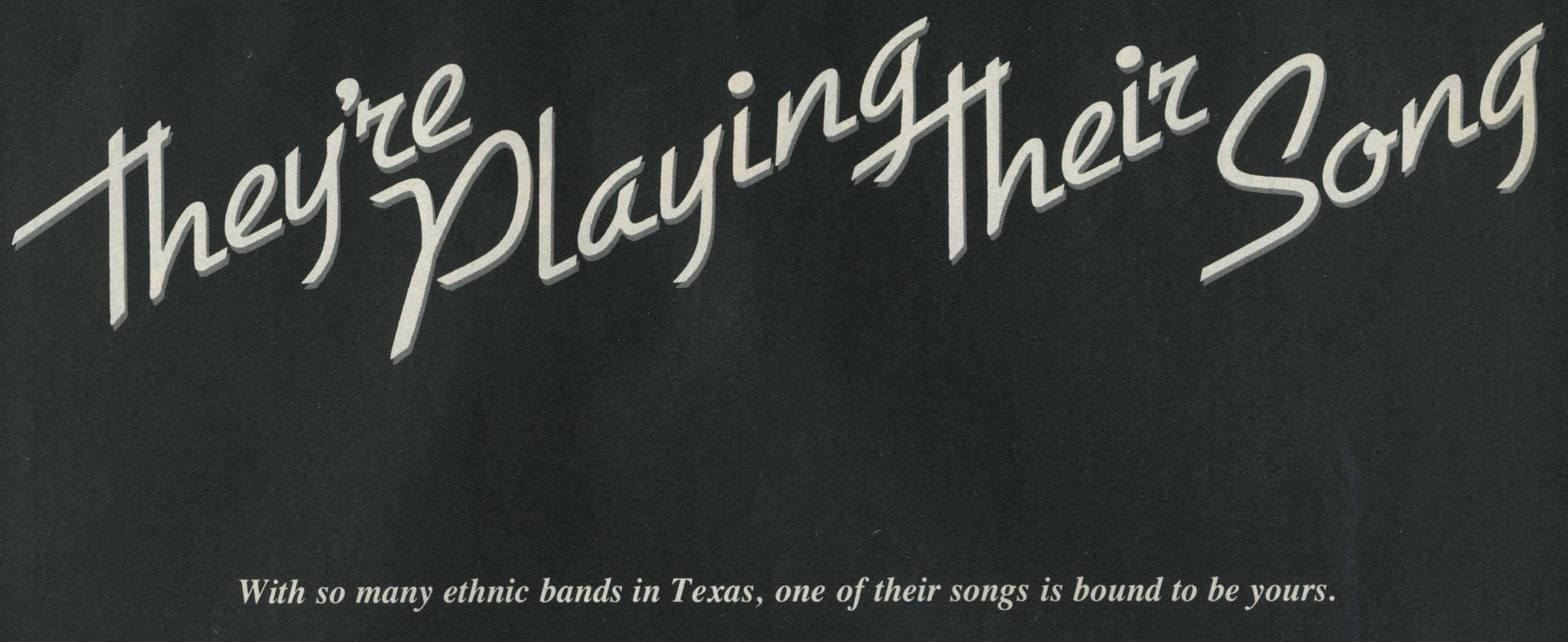

Hoyle Nix and the West Texas Cowboys (“That’s ‘Cowboys,’” says Nix, “not ‘Playboys’”) have been together since 1946. If he seems adamant about the name, it’s because he’s had a lifetime of being confused with Bob Wills’ band. Both are Western swing bands, but while Wills achieved national recognition in the thirties and forties, Nix’s group is a household word only in the 250-mile radius around Big Spring in West Texas, where the Cowboys play every Saturday night at Hoyle Nix’s Stampede club. The Stampede is a dancing crowd where you can expect to see deftly executed Texas two-steps, cotton-eyed Joes, and put your little foots. “We play by ear,” says Nix. “I might whistle a tune in the car on the way to a dance, but we’ve never rehearsed in the thirty years the band’s been together.”

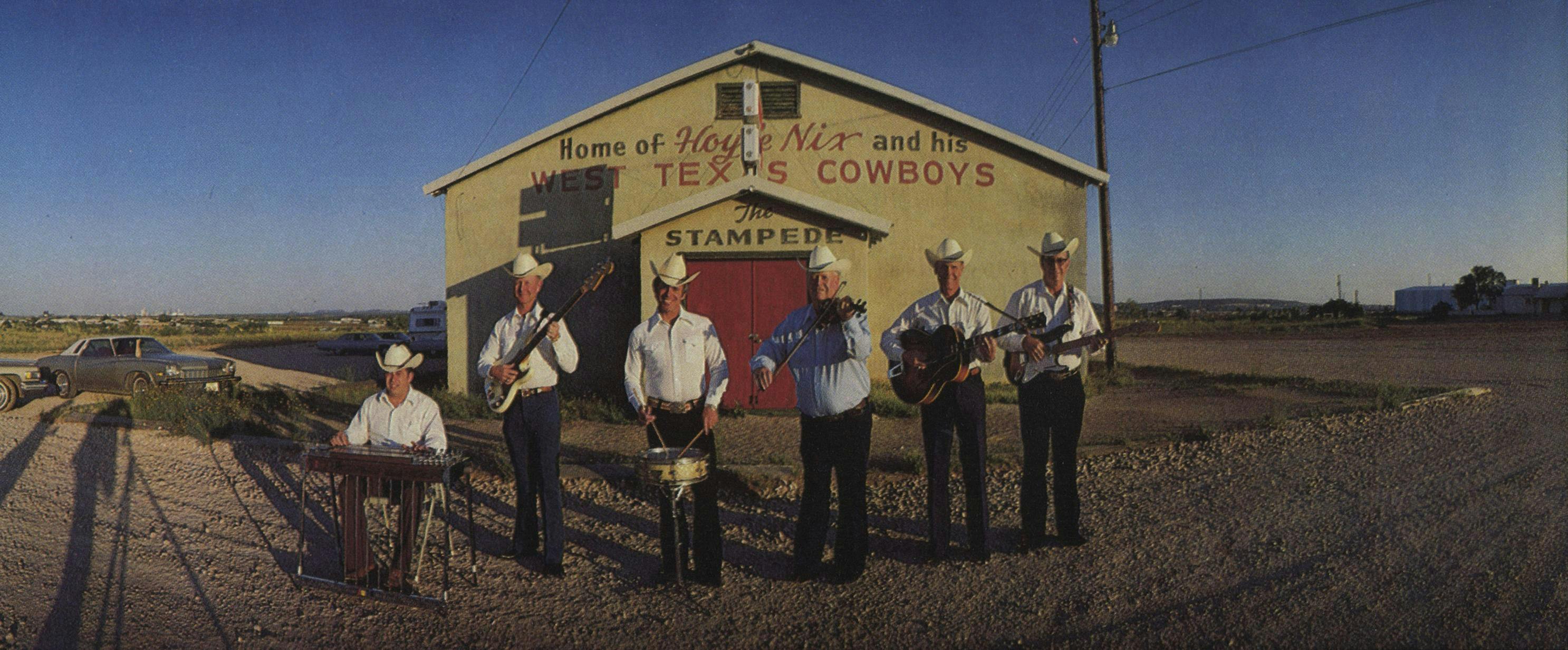

The Voices of the Mainland are an oddity among ethnic bands, and bands in general: they are a nonprofit organization; any money they receive is given to charity. Quite fitting for a gospel group. The Voices have been raised together in song for eleven years now, performing in churches in the Gulf Coast area, especially in their hometown of Texas City. Some of the Voices also play instruments, including lead guitar, rhythm guitar, bass, and electric piano, but percussion is left to an always-willing congregation. As for their music, lead vocalist Robert Maxey says, “Gospel brings people back to God, to themselves.” “Amazing Grace,” according to Maxey, is “everybody’s favorite these days,” but their biggest request currently is the Dixie Hummingbirds’ “Christian Automobile.”

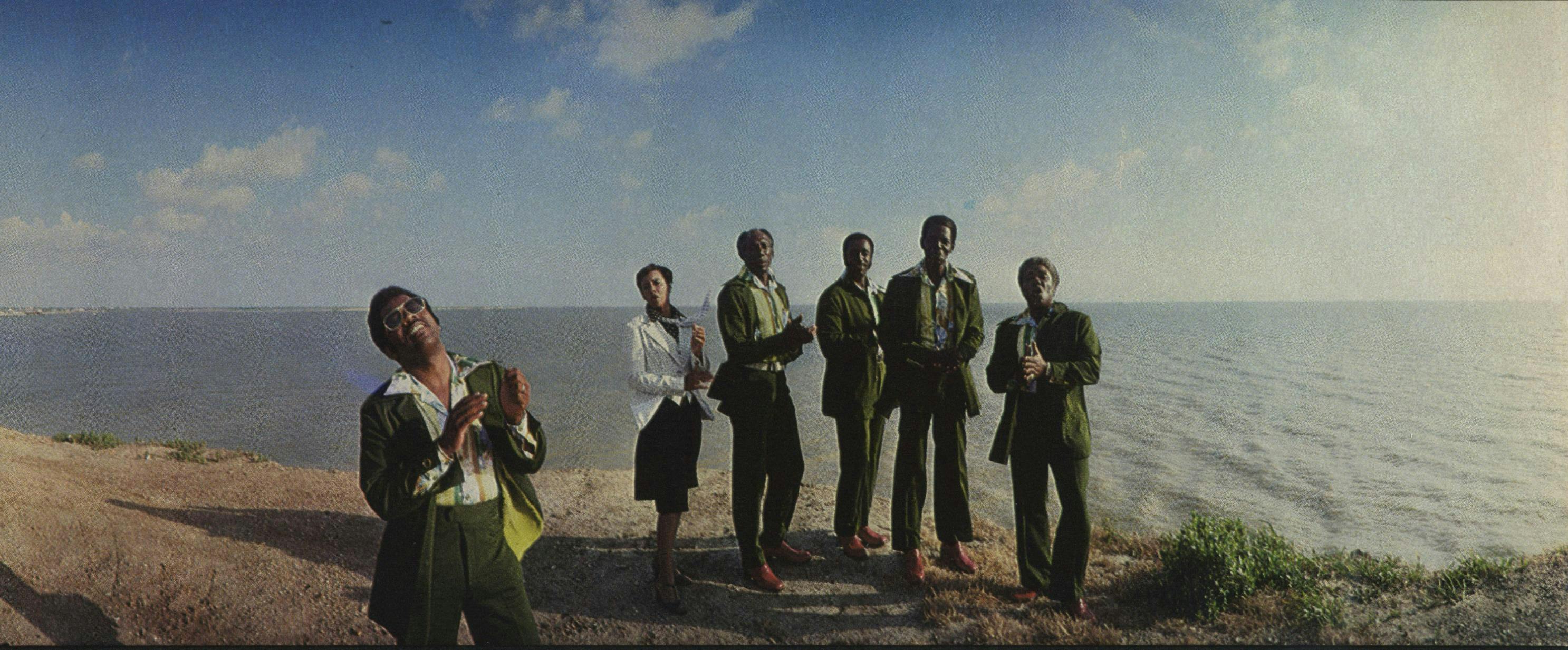

Mal Fitch Orchestra plays to a rarefied ethnic group: middle- and upper-class white folk. His is the most popular society and convention orchestra in the state. A list of his performing credits includes every governor’s Inaugural Ball since John Connally’s second term, the Dallas Petroleum Club Ball, and just about every debutante and charity dance in Texas. The orchestra is versatile enough to be all things to all audiences, performing with as few as twelve pieces to as many as twenty-five. “People in Texas are sophisticated about music,” Fitch says. “We’re playing Basie charts here, and I don’t know if we could do that at a society dance elsewhere. When I was younger, the satisfaction was in getting the jobs. As I get older, being able to please a cross section of people—that’s the biggest thrill.”

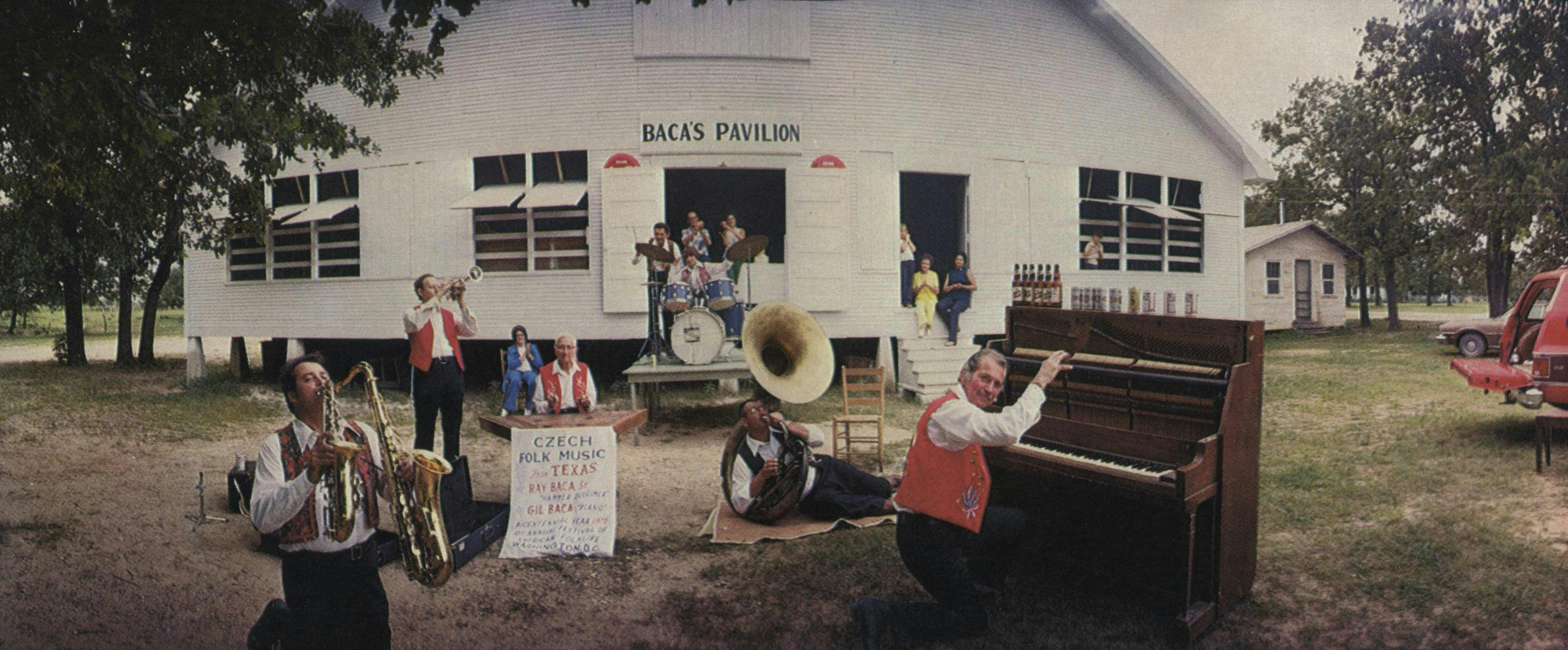

The Baca band, led by Gil Baca, bills itself as the oldest family band in Texas. Founded by Gil’s grandfather, they’ve provided the citizenry of Fayetteville with their own brand of Czechoslovakian polka music since 1892. It’s Ray Baca’s 120-string hammer dulcimer, played with mallets, that makes the band unusual. The Baca band has performed at folk festivals at the Smithsonian Institution since 1967, at the Texas Folklife Festival in San Antonio, and at the Presidential Inauguration in 1972, but none of these equals the thrill of playing old opera houses in Czechoslovakia in 1972. Gil Baca and his band found the Czech audiences receptive to a variety of sounds, including a little country music and some Johnny Cash songs, but “when we sang a polka, they went wild. They didn’t know we could talk the stuff.’’

The Baca band, led by Gil Baca, bills itself as the oldest family band in Texas. Founded by Gil’s grandfather, they’ve provided the citizenry of Fayetteville with their own brand of Czechoslovakian polka music since 1892. It’s Ray Baca’s 120-string hammer dulcimer, played with mallets, that makes the band unusual. The Baca band has performed at folk festivals at the Smithsonian Institution since 1967, at the Texas Folklife Festival in San Antonio, and at the Presidential Inauguration in 1972, but none of these equals the thrill of playing old opera houses in Czechoslovakia in 1972. Gil Baca and his band found the Czech audiences receptive to a variety of sounds, including a little country music and some Johnny Cash songs, but “when we sang a polka, they went wild. They didn’t know we could talk the stuff.’’

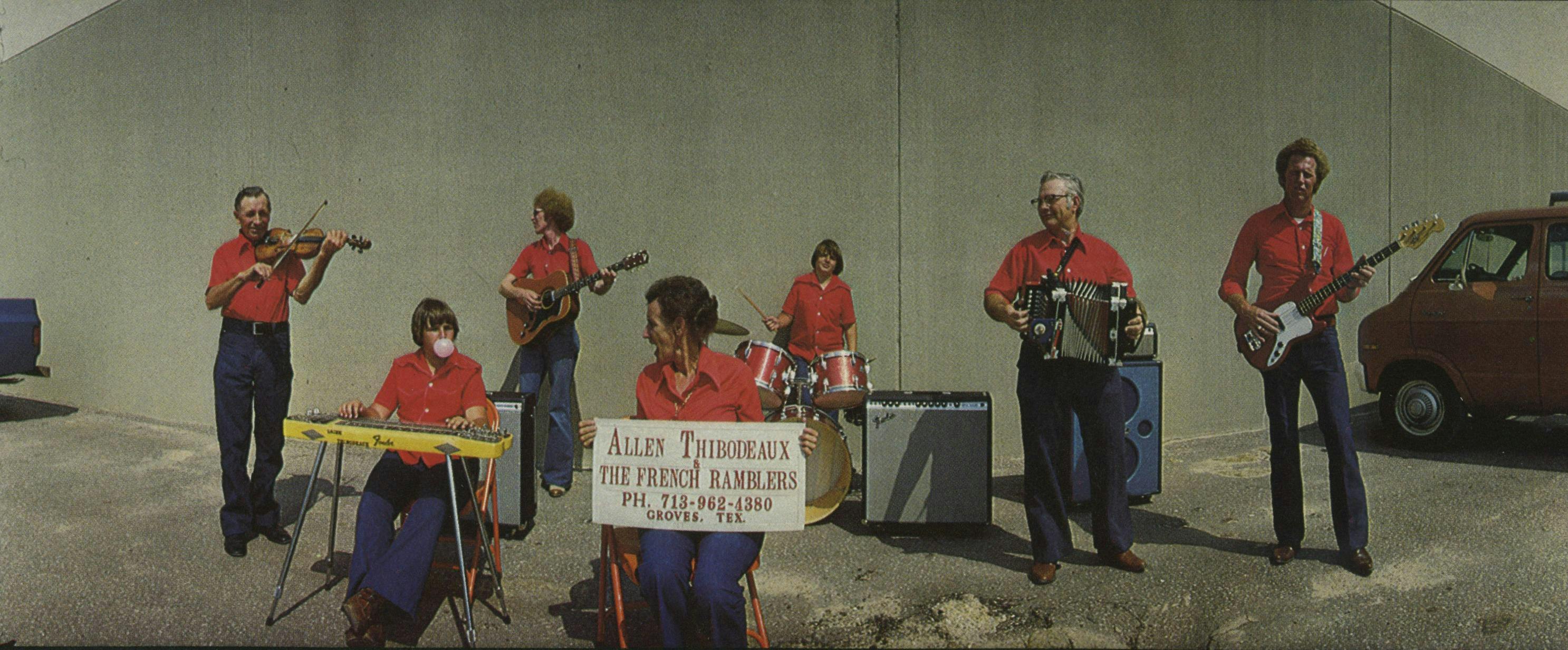

Allen Thibodeaux and his French Ramblers do, in fact, ramble. Every weekend the band, which includes Thibodeaux’s twelve-year-old twin sons, travels to Cajun clubs in Southeast Texas and nearby parts of Louisiana (they’re originally from Sulphur, Louisiana). But every other Sunday they play at the Rodair Club, which is across the street from some oil refineries in their home base, northwest Port Arthur. Unlike better known Cajun groups, the Ramblers’ roaming is still pretty limited. They’ve played at the Texas Folklife Festival in San Antonio for the last three years and at the Gumbo Cookoff in the Astrodome last year. Their music is almost pure Cajun: “Jole Blon” (which Mrs. Thibodeaux says is the Cajun national anthem), “Cankton Two-Step,” and Allen’s new composition, “Let’s Go Get Drunk.”

Allen Thibodeaux and his French Ramblers do, in fact, ramble. Every weekend the band, which includes Thibodeaux’s twelve-year-old twin sons, travels to Cajun clubs in Southeast Texas and nearby parts of Louisiana (they’re originally from Sulphur, Louisiana). But every other Sunday they play at the Rodair Club, which is across the street from some oil refineries in their home base, northwest Port Arthur. Unlike better known Cajun groups, the Ramblers’ roaming is still pretty limited. They’ve played at the Texas Folklife Festival in San Antonio for the last three years and at the Gumbo Cookoff in the Astrodome last year. Their music is almost pure Cajun: “Jole Blon” (which Mrs. Thibodeaux says is the Cajun national anthem), “Cankton Two-Step,” and Allen’s new composition, “Let’s Go Get Drunk.”

Los Alegres de Terán is a very small ethnic band; it consists of two men: Eugenio Abrego on accordion and Tomas Ortiz on bajo sexto (a twelve-string guitar distinctive of northern Mexico and South Texas). They have performed together for more than twenty-five years, recorded over forty albums, and are the masters and chief exporters of Norteño music, a style indigenous to the Texas-Mexico border area. Popular throughout Central and South America, Los Alegres are known for carefully harmonized vocals, simple accompaniment, and a repertoire of corridos or ballads of courage and romance. Arnaldo Ramirez of Falcon Records accounts for Los Alegres’ international following this way: “They’re the only Chicano group like this in history. Their songs are down-to-earth and they just get to people.’’

Los Alegres de Terán is a very small ethnic band; it consists of two men: Eugenio Abrego on accordion and Tomas Ortiz on bajo sexto (a twelve-string guitar distinctive of northern Mexico and South Texas). They have performed together for more than twenty-five years, recorded over forty albums, and are the masters and chief exporters of Norteño music, a style indigenous to the Texas-Mexico border area. Popular throughout Central and South America, Los Alegres are known for carefully harmonized vocals, simple accompaniment, and a repertoire of corridos or ballads of courage and romance. Arnaldo Ramirez of Falcon Records accounts for Los Alegres’ international following this way: “They’re the only Chicano group like this in history. Their songs are down-to-earth and they just get to people.’’

- More About:

- Music