This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Drew Pearson, Dallas wide receiver, carried this egocentric perspective into the most important moment of his athletic career: “I’m mad, disappointed. We’re gonna lose the game, we’re gonna be out of the play-offs, and I don’t have no catches.”

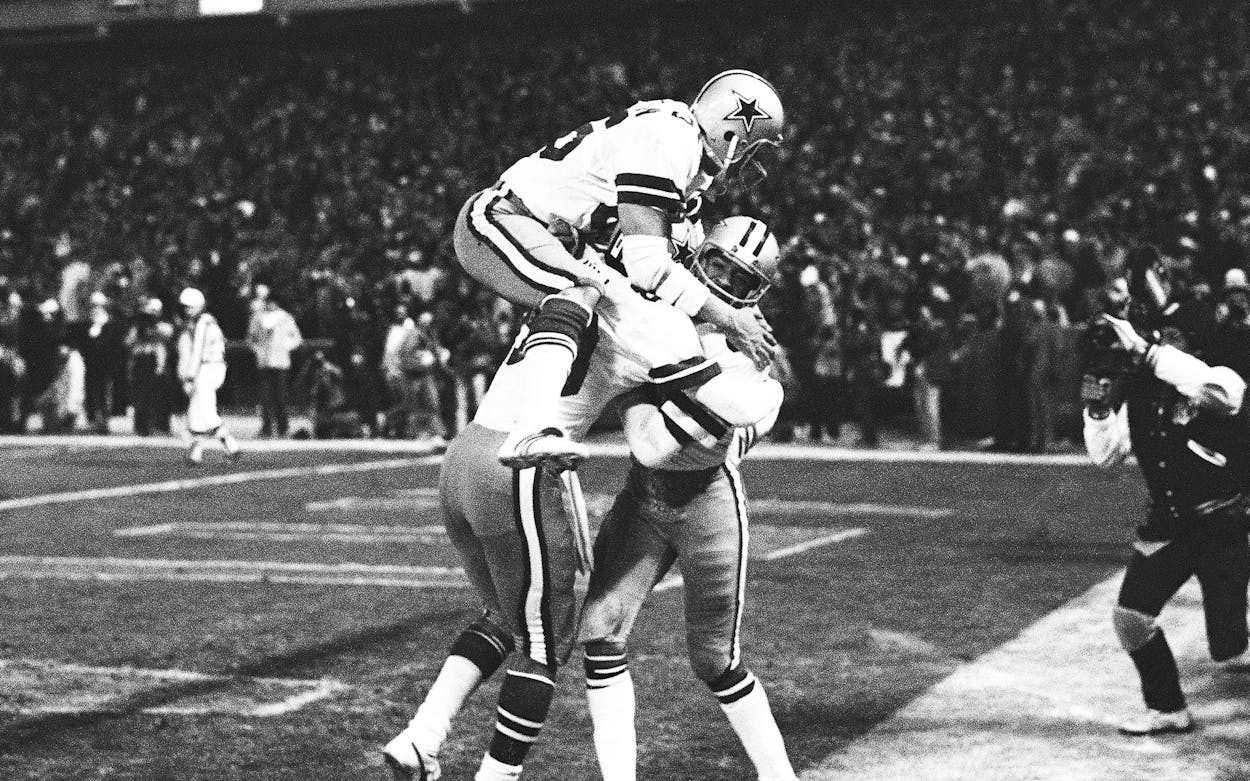

He got his catch—the last-minute reception of Roger Staubach’s Hail Mary pass against the Minnesota Vikings in the 1975 play-offs. Five seasons and three Dallas Super Bowls have gone by since then. Pearson has caught other passes in each of the Cowboys’ last sixteen play-off games. But for him, the details of that blustery Saturday in Bloomington, Minnesota, have scarcely blurred or faded. The memory makes him smile.

“Because of the game plan and what the Vikings were doing, that whole game I wasn’t getting any action. But when we hit the field that last time, we were down by four points with ninety-one yards and one minute, twenty-four seconds to go. No doubt in Roger’s mind who he was going to. Coach Landry wasn’t calling the plays anymore because we didn’t have time. In every huddle Roger asked me what I could get open on. I wound up catching four passes for the whole ninety-one. At one point it was fourth down and twenty-two to go. I told Roger I’d run a post corner—take the guy in, then break out. Roger read me in, then gave a pump fake, and I gave my guy the move. Nate Wright, the Minnesota cornerback, stayed right with me. I had to jump for the ball, and if Nate had laid off, I couldn’t have gotten my feet down inside the chalk. The ball goes over; we lose. But he hit me while I was up, and the ref said he forced me out of bounds. That gave us the first down at midfield.

“When I got back to the huddle Roger asked me, ‘Are you ready to go again?’ I said, ‘No, man, let me catch my breath.’ So he threw incomplete to the other side. Back in the huddle he said, ‘Well? Twenty-four seconds . . .’ I told him I’d give the guy another inside move and then take off. When I came off the fake, Nate Wright and I were running even, step for step. I knew I had a chance. Roger laid the ball up, but it was underthrown a little bit. I was able to put on my brakes, while Nate’s momentum carried him forward. The ball hit my hands and slithered. I thought I’d dropped it. But then there it was, stuck between my hip and elbow.”

Pearson sashayed the last few steps into the end zone—a fast man’s sleepwalk. In celebration, he threw the ball high and far. In return, a hurled whiskey bottle knocked a nearby official cold, an ugly reminder of that other world out there—hard, anonymous, and real.

“To hear the quiet of that Minnesota crowd. After yelling their throats raw all day . . . a total absence of sound. And when the Cowboys got back to Dallas, the response from the fans here was unbelievable. This town was mine.” Pearson adjusted his sunglasses and pulled his short-billed cap closer to his nose. “There are fifty-five thousand people in the stadium watching the quarterback, and when he releases the ball, all those eyes move to the receiver. Even though the defensive back crowds into the picture, the camera’s on you. You’re the ballet dancer who has the grace to go up in the air and snag it. You’re the gymnast who can take the lick and roll, then bounce back up. You get to spotlight the skills that got you here. It’s a team sport. You’re out there with ten other guys. But the individualism of the wide receiver is never snuffed out. You still get to be yourself. I don’t think I’d like football if I had to play another position, to tell you the truth. Too physical. The pounding, day in and day out, that running backs and defensive backs have to take . . . With this body? I couldn’t handle it.”

“The most spectacular running back is lucky to average 5 yards a carry. Last year the Dallas wide receivers averaged 15.5 yards a carry. They make the plays that bring the crowd to its feet. They are artistes and prima donnas, the equivalent of a symphony’s violin soloists. But the athletic demands and extreme violence of their medium set a clock ticking loudly in their heads.”

Wide receivers. Everything about them sets them apart. Other offensive players approach their tasks in humpbacked and splayfooted three-point stances. Dallas wide receivers await the start of each play with their weight lightly balanced on their left feet. A few inches to the rear, the toe cleats of their right shoes caress the turf, poised to dig in and spring. They rest their hands on their hips, or they let the wrists dangle. Offensive linemen tape their hands and wrists; running backs are content with single wristbands like tennis players wear. Wide receivers stack the sweatbands on their arms like the bracelets of an overdressed woman. It’s a matter of function as well as style; leather adheres more readily to thick cotton than to slippery skin. Remember the ball that almost slithered from the grasp of Drew Pearson.

The most spectacular running back is lucky to average 5 yards a carry. Last year the Dallas wide receivers averaged 15.5 yards a carry. They make the plays that bring the crowd to its feet. They are artistes and prima donnas, the equivalent of a symphony’s violin soloists. But the athletic demands and extreme violence of their medium set a clock ticking loudly in their heads. Imagine telling a Sir Laurence Olivier that he has roughly eight years to accomplish whatever he can.

The Cowboys invented the modern wide receiver in the 1965 season when they introduced Bob Hayes, a world record holder in the hundred-yard dash who terrorized opposing defenses; in 1970 he averaged 26.1 yards a catch. Last year Drew Pearson broke Hayes’s record for career receptions with the Cowboys. But while Pearson’s 378 catches through 1980 included 37 touchdowns, Hayes scored 71 of the 365 times he caught the ball. Bob Hayes revolutionized the game.

Last year the Cowboys threw on 43 per cent of the plays from scrimmage, with a completion rate of 59 per cent. That means the passing game advanced the ball only 25 per cent of the time, but it accounted for 59 per cent of the team’s total yardage. So much for three yards and a cloud of dust. In the pros, the name of the game is longball.

The Dallas Cowboys employ three veteran wide receivers: Drew Pearson, Tony Hill, and Butch Johnson. Each one is convinced that he’s the best in the league. While each self-estimate is ego-inflated, collectively the claim has merit. Only two other teams in the NFL—the San Diego Chargers and the Pittsburgh Steelers—boast equal strength on the flank. Over the last eight years, sportswriters have voted Pearson All-Pro three times, and his peers, the players, agreed by electing him to the post-season Pro Bowl each of those years. Last year the Pro Football Hall of Fame named Pearson to its all-decade team of the seventies.

He’s done it all, yet he finds himself, at thirty, in a tenuous position. Roger Staubach, the great quarterback who had an almost irrational confidence in Pearson, has retired. The relations between a passer and his receiver are intimate and intuitive, like those between a baseball pitcher and his catcher. Pearson has to seal that bond and curry that favor all over again with Staubach’s successor, Danny White, and he doesn’t have much time to work with. He has reached the stage at which he feels pressed to overachieve, in order to prove he hasn’t lost what he had in the seventies. His employers have a maddening way of subtly and slowly easing older players off the field.

Tony Hill is the dazzling young comer. In the three years he has started for Dallas, NFL players have sent him to the Pro Bowl twice. But sportswriters haven’t followed suit with All-Pro recognition, which rankles Hill. Though he has proven himself on the field, he lives in Pearson’s shadow as far as the media are concerned. He wants a share of the public service TV spots, too. He doesn’t want to leave Dallas, but he wonders if the rewards of exposure and remuneration might come easier with another team. After all, neither the career nor the bank account of his role model, the great receiver Paul Warfield, suffered from a Cleveland-to-Miami trade. And although Hill is five years younger than Pearson, he can’t be certain that patience will pay off. One blow can put a pro football player out on the street.

As long as Butch Johnson, Dallas’s third wide receiver, plays for Dallas, he’ll never go to the Pro Bowl. He hasn’t been able to break into the Cowboys’ starting lineup. Yet other players respect him as much as Pearson and Hill because of what he has accomplished despite the circumstances. He doesn’t get to warm up, he hasn’t studied the defensive backs, adrenaline hasn’t pumped him into the rapid flow of the game. He comes in cold and still makes the play. Johnson doesn’t like his situation. In his sixth year, he’s getting long in the tooth himself, and now he’s being pushed by a talented rookie, Doug Donley. For most of his career, Johnson has seethed, complained, and begged to be traded. But his employers are reluctant to let him go: he’s too valuable.

None of these guys can poor-mouth very convincingly. Pearson and Johnson drive new Mercedes-Benzes; Hill has a Porsche with tags that read DIAL 80. But like all professionals, they assess their market value in relative terms. Baseball and basketball players of comparable stature make five to eight times as much. As a group, receivers rank fourth in salary behind quarterbacks, running backs, and defensive linemen. And the Dallas front office is known for its stability and sound business practice, not its largesse. The management’s outlook isn’t malevolent; it’s just different. For a period of time after he bought the Cowboys franchise Clint Murchison could depreciate the players as tax liabilities. If the general manager, Tex Schramm, loses a player, he simply buys the services of another one. This season’s touted rookie, Doug Donley, was one year old when head coach Tom Landry took his first Dallas team to camp. When a player enters the Cowboys’ offices on the North Central Expressway to negotiate his contract, it may seem a matter of life and death importance—to him. To the fellow on the other side of the desk, he’s just the current flanker.

“None of these guys can poor-mouth very convincingly. Pearson and Johnson drive new Mercedes-Benzes; Hill has a Porsche. But they assess their market value in relative terms. Baseball and basketball players of comparable stature make five to eight times as much. As a group, receivers rank fourth in salary behind quarterbacks, running backs, and defensive linemen.”

Those dynamics create tension among the players with whom each wide receiver has most in common—other wide receivers. They compete for shares of the team dollar, they compete for media attention, they compete for playing time. All of them suit up, but only two can start. And while they have to subordinate their own interests to those of the team, they even compete on the field. On the way back to the huddle, they murmur in the earhole of the quarterback’s helmet. At the end of their routes, they jump up and down, waving their arms to get his attention.

Throw the ball to me.

Drew Pearson is six feet tall and had to lift weights hard to get up to his playing weight of 183. Compared to other wide receivers, he’s not exceptionally fast. His moves are fluid and deceptive: he leans left when he’s going right, shifts gears three times in a fifteen-yard route. “Drew’s a former quarterback,” says Danny White, “and he thinks like a quarterback. He can completely break a route, yet I know where he’s going. He sees the same thing I see. If he’s running a sideline route and I throw behind him, he doesn’t have to stop and spin around. He adjusts his speed so that he catches the ball out in front of him. That makes me look good, which is nice, but it also means he’s in position to turn the play upfield after the catch. He’s always in control.”

Pearson grew up on the playgrounds of South River, New Jersey. He tries to make his opponent so mad, so tensed to strike, that for an instant he forgets his purpose on the field. Pearson glowers, chops his steps in anticipation of the contact, then dips a shoulder and flees—with an eye out for the ball. He’s psyching himself up as well. He runs the sideline routes with precision, and he can get open long. But his specialty is the catch over the middle, where the collisions are most ferocious. He likes to go inside. Total concentration enables him to make those game-winning catches in the crowd. He may hear the defensive backs coming, but he sees nothing but the ball.

Yet he’s no longer the leading Dallas receiver. Pearson has had two thousand-yard seasons in a nine-year career. In 1976 he led the National Football Conference with 58 catches; he was second in 1974 with 62. As Tony Hill goes into his fifth season, he has caught 60 passes each of the last two years for 1062, then 1055, yards. While Hill’s numbers reflect the extension of the NFL schedule from fourteen to sixteen games, his three seasons as a starter were an auspicious debut. “Tony’s got the depth perception,” says Danny White. “As soon as he makes his break and turns his head, he knows where the ball’s going to end up. He picks up the ball quicker than anybody I’ve ever seen, and consequently he gets to more balls, especially deep passes. Tony Dorsett has a tremendous burst of speed when he sees a hole. Tony Hill shows that same kind of burst when he runs under a ball. I try to overthrow him in practice sometimes—and fail. I think, ‘There’s no way he can get to that one.’ But he does.”

Many receivers extend their arms prematurely when they chase an overthrown pass. It slows them down and messes up their eye-hand coordination. With the build and stride of a quarter-miler, Hill just stretches out and runs. When the time is right, he dips forward slightly at the waist, drops his hands toward his knees, and lets the ball fall into them over his shoulder.

Of the three, Hill is the most dangerous runner after the catch. Charlie Waters, the Dallas safety whose business is the study of receivers, contends, “Athletes have a kind of gyroscope—a core of balance somewhere below the navel. Tony’s strength is in his legs, and he knows where that gyroscope is, which enables him to put stress on his joints far beyond what anybody else can. His change of direction is the best in the league. He’ll catch a pass on a little stop route and put on four moves, where most guys couldn’t manage more than two. He starts out one way, makes a drastic cut back the other way, then spins completely around. I used to think he’d get hurt doing that, but he has an innate feeling for where the contact’s coming from.”

At six feet two and 198 pounds, Hill is the biggest of the three, and he’s still filling out. He has the physique to intimidate defensive backs the way Washington’s Charley Taylor and Kansas City’s Otis Taylor did. But, of the Dallas receivers, he is the least fond of contact. And unlike Pearson, he reserves his jive for his teammates. He doesn’t say much out there. “I’m a little bit more sane than Drew. I don’t want to give a defensive back any reason to give me an unnecessary hit; I take enough cheap shots as it is. Anyway, that’s not my style. I want kids to say, ‘Hey, I’m like Tony Hill,’ the same way I used to say, ‘Hey, I’m like Joe Namath.’ The object of the game isn’t to beat up on somebody. My game’s an art.”

Butch Johnson is two years older, one inch shorter, and six pounds lighter than Hill. And, according to the Dallas coaches, he’s a critical step or two slower. His relations with the coaches are polite, professional, and strained. The closest Butch Johnson came to starting for Dallas was in 1977, when Landry used him and Golden Richards to shuttle play calls from the sideline to Staubach. The next year Landry shipped Richards off to the Bears and promoted Hill over Johnson. Johnson’s frustration partially accounts for his reputation as the Cowboys’ meanest wide receiver. “He’s brutal on the crackback blocks,” says Charlie Waters. “He used to delight in decking me at practice.”

Minor injuries and an understanding of the league’s protocol have mellowed Johnson to a degree. Mike Ditka, the former tight end who now coaches the Dallas receivers, says, “Butch is an excellent blocker, and if he was a regular he’d catch forty or fifty passes a year. He doesn’t have the finesse of the others, but he has a lot of discipline in what he does. He’ll do whatever you ask—when he’s happy. He’s happy now, but he hasn’t always been. It’s tough to come off the bench and play. It’s hard on you mentally, and maybe you don’t perform as well physically as you could. Butch knows his limitations, and I think he understands the situation now. If the opportunity arises, he’ll be playing more this year. If it doesn’t, he won’t.”

Johnson’s strengths and limitations are intertwined. White says, “I’ve worked more with Butch because we broke in the same year and played on the backup team together. He’s a precision route-runner. If I tell him to run a square out, he runs exactly six steps, breaks it square, and hits that sideline at twelve yards every time. I never have to wonder where he’ll be.” But that precision also makes him more predictable for the defensive backs. With the flapping hands and the breath expulsions of a sprinter, he shows his speed, and corner backs adjust accordingly. He may have to work a little harder than the others at catching the ball, but he’s a tough and flashy runner after the catch; the Cowboys used him for punt and kickoff returns earlier in his career. And despite his curtailed playing time and alleged liabilities, he has a gift for the play that breaks a game open.

The last time the Cowboys won a Super Bowl, it might be recalled, was in January 1978, against Denver. In the third quarter the outcome was much in doubt until Johnson made a classic diving, fingertip, end-zone catch of a 45-yard pass from Staubach. He made that catch, which remains a favorite in the highlight films industry, even though he had broken his right thumb while blocking earlier in the game. “I got nothing from the organization for that catch,” he says. “That was the burying point for me. After that Super Bowl, all the fans heard was Tony Hill, Tony Hill. That issue was already decided. The only thing that happens suddenly around here is when a rookie gets cut. ‘Personnel decisions’ are worked out a year in advance.”

Johnson is the most outspoken of the three, and he doesn’t sound very happy. “Everybody else is afraid to talk. ‘Protect your position.’ Well, I don’t have a position to protect. What are they gonna do? They can’t hurt me any worse than they already have.”

The drudgery of practice is the bane of all football players, but it’s more bearable for the wide receivers than for the others. Wide receivers run wind sprints constantly, but at least they don’t have to thunk and groan against hydraulically powered tackling dummies, and their eyebrows don’t bleed from the chafe of their helmets in contact. They seem to have more fun out there. Every pass is a challenge, a chance to show off. They cheer and razz each other. If they drop one, they pitch a small fit and regard the fallen ball as if it were a rotten, skunk-chewed melon. During informal workouts, they wear sweat pants, T-shirts, and carefully selected caps: Coors beer, the New York Yankees. This year’s winner is Johnson’s mock-up of the Philadelphia Eagles’ helmet. The silver plastic wings flare out from the green-billed cap like those of the Mercury who delivers flowers.

On Saturday mornings before a home game, the Cowboys unlock the gates of their practice field near Abrams Road and the LBJ Freeway. Children flock to the light workouts with moms in tow and autograph tablets in hand. Johnson, a natural comic, becomes the showboat on these occasions. His flapping hands and elaborately slow returns to the huddle make kids laugh. A line from the Bill Murray movie Stripes amused him enough this year to become his motto. Johnson can turn to a group of kids, motion one-two-three, and they shout in chorus: “Dat’s the fact, Jack!”

Supervising a noncontact drill during a recent practice, Landry steps into his old cornerback position and backpedals impressively for a man his age. “Did you see that?” Pearson demands loudly. “Coach Landry chucked me! I don’t believe it.” a member of the front-office staff murmurs, “I bet he’d like to clothesline those guys. They say he was that kind of player.” Hill slouches, swings on his heels, and babbles. “Tony’s a talker,” says Mike Ditka, “which is okay, because he backs it up on the field. You just have to be careful that you don’t aggravate your teammates.” As they take their laps, Tony Dorsett looks at the sky, shakes his head, and tells Hill, “You’re the only guy I know who can talk nonstop while he’s running.” In the weight room, running back Robert Newhouse chases Hill away: “Man, will you be quiet? You’re spittin’ on me!”

Out on the field the receivers are running deep post routes for Danny White and his backup, Glenn Carano. An assistant coach, Al Lavan, yells, “Forty-one . . . forty-three!” each time a catch is made. The quarterbacks and receivers try to time the passes and routes so that they intersect exactly 45 yards out. But this time White’s pass is overthrown. Johnson looks up, then lowers his head and accelerates. He runs flat out, as if guided by the striped lanes of a sprinting track. He looks up again and lunges. He juggles the ball on his fingertips, then pulls it toward his chest as he starts to stumble. He hits the ground hard, rolls on his shoulder, and somehow lands on his left knee, right foot extended like Al Jolson. He flips the ball back over his head. “Dat’s the fact, Jack!” he exults. Then he struts toward the shower.

The secret with the kids is to keep moving. Sign autographs all the way to the door. If a star player stops to accommodate all the thrust-out ball-points and cries of “Please,” other kids come running, and then they have him for the duration. Tony Hill says he doesn’t mind. “When I was a kid I used to go to a government-funded sports camp in Long Beach. The Rams had their training camp at Long Beach State then, and we’d get the chance to sneak over and meet the players. That was the greatest thing that ever happened in my life. They don’t have enough sports camps now, the government’s cut the funds off. This year I started my own camp at Los Alamitos that wasn’t anything large because I wasn’t equipped to do it large. What I wanted was a quality camp where kids from all ethnic backgrounds could come, kids who are economically deprived. I brought some at my own expense. All kids need somebody to look up to, and 1 wanted to make it possible for those kids to go to sports camp and have the same joy I had.”

He warms to the discourse. “There needs to be some way to keep kids off the streets and keep their minds moving in the right direction. Take kids who’re sixteen or seventeen or eighteen, they have terrible study habits in school, they’re interested in football, and that’s it. People say, ‘They can’t cut it, they’re doing D or F work,’ but a lot of times that’s nothing but a lack of maturity. I have friends now who say, ‘I wish I’d gone to college,’ but it’s too late. Whereas in my case I always had my parents’ support, and when I got the athletic scholarship, at first I achieved what I did in school for them, not myself. But then when I was a sophomore and junior I realized it was for me. It takes time for some kids to develop, and I don’t think they should be victimized. A mind’s a terrible thing to waste, you might say.”

A nice, breezy kid from Southern California. Radiating self-confidence, he looks people in the eye and expects them to do the same. Hill says he never had a doubt he’d make it someday in the bigs. As a high school pitcher, he once struck out eighteen batters in a seven-inning game. He and tight end Billy Joe DuPree are now the best players on the Cowboys’ basketball team, which plays benefit games against disc jockeys and ringers in the off-season. As a public-school quarterback, Hill always demanded number twelve because his heroes were Joe Namath and Roger Staubach, but Stanford recruited him as a receiver. “I used to watch the Dallas Cowboys on TV all the time,” he says. “Drew Pearson broke into pro ball during my freshman year, and I idolized him. Stanford wanted us to get down in three-point stances. Not me. I wanted to stand up straight like number eighty-eight.”

Hill almost likes training camp in Thousand Oaks, with its hazy California sun and cool Pacific winds. His dad drives up to watch the Cowboys work out. Hill checks out his real estate holdings in Huntington Beach, home of sailboat yachts and disco slam dancing. The coaches at California Lutheran, where the Cowboys train, conduct their own football clinic for grade schoolers, and John Wooden, the former UCLA coach, hosts a basketball camp on the campus. There are plenty of opportunities to be admired, to sign autographs, to return those favors once bestowed by the Rams at Long Beach State. He has a degree in political science and plans to study business at UT-Dallas. He talks about his many “utensils to work with” and “avenues to pursue.” A bachelor, he really hasn’t given the world outside athletics a great deal of thought, and why should he? He’s 25 years old, and he runs like a deer.

But there’s angst in Tony Hill’s paradise. Today, as he runs a deep post route for White, he suddenly grabs the back of his right thigh and goes hopping through a crowd of startled kids crying, “Ow! Ow! Ow!” He limps straight to the trainer’s table, then to the whirlpool. A hamstring pull feels like a giant rubber band has snapped inside your leg; a bad pull could rob Hill of his speed all season. The only rap on him is his fragility. He was still available for Dallas in the third round of the 1977 draft because of a history of injuries at Stanford. “I had a knee operation when I was a fresh,” he says, “and it was the worst thing that ever happened to me. The pain, the surgery, the rehabilitation. I decided then that if I ever had to have another operation, that’s it for me. I’m through.”

Despite a chronic shoulder dislocation, he was lucky in Dallas until the last minute of last year’s regular-season finale against the Eagles. After catching his sixtieth pass, he took a shot that bruised his left knee and deposited a large clump of calcium in his thigh. In the following week’s play-off game against the Rams, the shock of a chest-high tackle traveled downward and erupted in his weakened leg. He hobbled through the Atlanta game, but in the NFC title game against Philadelphia, he tried and couldn’t go. After the loss, some of his teammates—especially Butch Johnson—suggested he was dogging it. And, his freshman vow notwithstanding, during the off-season he submitted to the organization’s recommended surgery to correct the loose shoulder joint. “For three years I’ve essentially been playing with one arm, simply because I didn’t want to stand the pain of having it cut.”

As Hill soaks in the whirlpool after the workout, his agent, Mike Trope, is in Thousand Oaks demanding a renegotiation of Hill’s contract with the Cowboys. “I’m not playing football for fun anymore. Those days are behind me,” says Hill. “I’d like to end my career in Dallas, but if I have to go somewhere else for a fair and honest salary, I will. I’m not making outlandish demands. It’s just like any other job. If you feel like you’re doing an adequate job, and another guy who’s doing no better makes three times as much, it kind of gets you down.”

Was this a veiled and exaggerated reference to his teammate and idol, old number 88? More likely he was talking about Johnny “Lam” Jones, the former Texas Longhorn and second-year New York Jet whose salary of $264,286 as a rookie made him the highest-paid wide receiver in the NFL. Last year’s average salary for receivers was $75,968, the median was $62,500, and the low was $22,000. While keeping the Dallas figures to himself, the Cowboys’ personnel director Gil Brandt explains the organization’s position with an air of unlimited patience. “I think Tony’s smart enough to realize he has a great future in Dallas and, because of that Stanford education, not only as a player. Dallas is a city where a black has a great opportunity now. Also, the cost of living in Dallas is about thirty per cent less than in New York City, thirty-five per cent less than in Boston. So you can’t really compare salaries throughout the league. We have a salary structure that pays people according to their relative value to the team. If the New York Giants are forced to pay more because of the higher cost of living and the fact that they haven’t been in the play-offs since the NFL-AFL merger, we can’t be tied to that. By the same token, we’re not the lowest-paying team in the league by a long shot.

“Tony’s under contract for another two years. He’d like to add some years to that contract. If we can work a deal that’s acceptable to us, that fits within our salary structure, and it’s one that he can live with, we’ll be more than happy to accommodate him. But we’re not going to destroy that structure for any player.”

Mike Trope has his hands full. While Hill anticipates a prompt settlement to a quiet dispute, the negotiations are making him nervous. He finally emerges from the whirlpool and dresses in Bermuda shorts and sandals. Danny White enters the California Lutheran locker room still sweaty and wearing his pads. Hill looks around, dips his head, and asks the quarterback, “Are there any . . . kids out there?”

“God, I guess,” says White, struggling to remove his jersey. He had looked like the Pied Piper, leading a phalanx of children across the freeway pedestrian bridge that connects the field house and the practice field.

Hill wrings his hands and paces. He stalls, hoping they’ll go away. Hurt and uncertain, he can’t face them. Not today.

“I came into the league without a distinction,” says Drew Pearson. “I wasn’t fast, I wasn’t big, I didn’t come from a great school, I wasn’t a number one draft choice. I didn’t set any records, and I never made all-conference.” A high school teammate of Redskins quarterback Joe Theismann, who went to Notre Dame, Pearson also wanted New Jersey in his rearview mirror; he had to settle for Tulsa. At a school that was on NCAA probation, he played under three head coaches. Every year he considered transferring. In his senior year he caught 33 passes for a team that won four games and lost seven. Pro scouts told him he might go in the sixth or seventh round of the draft.

“Which was a real downer, because the phone never rang,” Pearson says. “After the draft was over, Dallas offered me $150 to sign as a free agent, a salary of $14,500 if I made the team. I thought pro football was supposed to be a little more lucrative; I could make that working at some recreation center. Eventually Green Bay and Pittsburgh called, too. I came very close to signing with the Steelers because they offered me $1500 to sign and $16,500 if I made it. I needed the money bad. I’d just gotten married, and the rent was due. But I had to weigh the situation realistically. I went with Dallas because of their history with draft choices and free agents. Everybody gets the same look in training camp.”

The confidence of that decision impressed the Dallas front office. After all, the Cowboys’ six veteran wide receivers included Bob Hayes, Lance Alworth, and Otto Stowe. The coaches thought Pearson was too skinny, so they urged him to move to Dallas and start a weight lifting program. He wound up playing catch every day with Roger Staubach. “It was the month of June,” Pearson recalls. “Most of the veterans were taking vacations. Roger would meet me at the field, or rather, I’d meet him at the field at his convenience. No matter how tired I was, working in that hot Dallas sun, if he told me to run another route, I’d run it. Even if my tongue was hanging out. So when I got to training camp, Roger already knew what I could do. When it was my turn to go, he wouldn’t send the rookie quarterback up to throw to me. Our rapport just built from there. Off the field, he helped me get settled in Dallas, introduced me to the right people.”

According to Mike Ditka, Pearson made the team on the strength of a punt return in the 1973 exhibition game against the Rams. When Otto Stowe broke his leg during the seventh game, Pearson vaulted past the others to start, and he led the team in catches the rest of his rookie year. Pearson’s catches accounted for roughly a fourth of the 22,700 yards attributed to Staubach during his career. Of course, Staubach has since gone on to Rolaids commercials and CBS commentary on NFL games. Pearson’s time is not far away, either. He has prepared for retirement by investing, with Cowboys tackle Harvey Martin, in a barbecue restaurant near Love Field called Smokey’s Express. Because he started so low on the pay scale, he has had trouble making the salary advances that a player of his stature might expect. By renegotiating his contract often—securing his services two or three years at a time—management continues to bargain from the position of greater strength. When a player is under contract, Gil Brandt doesn’t have to offer anything.

With his deep, resonant voice, Pearson has a good chance to move into broadcasting. Last year the Dallas CBS affiliate, KDFW, impressed by his spots on teenage alcohol abuse, offered him a job moonlighting in the Channel 4 sports department. “I thought I’d hate doing it,” he says. “I had to put on a tie and leave right after practice, and trying to get downtown in that traffic was just awesome.” But he enjoyed the work, and this summer he took part in a training program that introduced him to production, writing, and editing. His first solo story concerned the Dallas Mavericks’ participation in the NBA draft.

“I got to the station with all this tape and footage,” Pearson says, “then realized I had one minute on the air. Learning to pinpoint and condense was the hardest part. Eventually I’d like to do some network stuff. When I watch a football game on TV, the quality of the analysis disturbs me. Sometimes the information is just wrong. Sometimes they don’t say enough, other times they bring out more than the fan can absorb. And what really ticks me off about these ‘analysts’ is that they haven’t stayed current on the changes in the game. Why can’t a receiver run a certain route anymore? Why don’t running backs rule the game the way they once did? Why have teams gone to the three-man front? When I listen to Howard Cosell, he’s reaching way back for some of his stuff. Even Dandy Don Meredith—he used to be a quarterback, but he’s giving out old information for a new game. This is 1981.”

He apparently is not aware that his perspective will someday be just as dated, that people will soon say Drew Pearson “used to be” a wide receiver. “I know that I can do a good job in that field,” he says. “And who knows? Maybe Roger and I could team up one more time—in the booth.”

As Tony Hill hobbled through the pre-game warm-ups of last year’s NFC title game against the Eagles, Danny Reeves, then the Cowboys’ offensive coordinator, is said to have asked Tom Landry, “Well? Who’s going to start?” The implication was obvious, since Reeves had been advancing the cause of Butch Johnson for several years. Landry reportedly eyed his injured split end and said, “He looks all right to me.” While the story may be apocryphal, it underscores the conviction of one Dallas insider who says, “As long as Tony Hill has a pulse, Butch Johnson will never start for Landry.”

Johnson has a sparse moustache, a dark goatee, and a quiet manner of speaking that belies his flamboyant antics on the field. “I’ve never really been in the mind of anybody here,” he claims. “I don’t think I was ever seriously considered as a starter. I was a third-round draft choice, too, but the guys that come from the big schools are going to get the front office publicity, because that’s good for the alumni, and alums buy tickets. I went to California-Riverside. I’m the only player ever drafted into the pros from there, and there won’t be any more because they’ve dropped football. Nobody’s pressuring the Cowboys to give me a shot. They haven’t used me here, they’ve wasted away the larger portion of my career. Some good years, some very good years. Every year they build up this thing about competition, a training camp challenge; if you have the best camp, you get to start. What a con. They’re just trying to make guys like me really work out so the starters will feel pushed.”

But what about Landry’s professed desire to use three wide receivers much of the time this year?

“I believe that’s crap, man. I believe that’s intended for a stupid, gullible kid. I know exactly what’s going to happen, and it’s quite simple. They’re not going to start me, ever. I’ll continue to play when they want me to play. That’s it.”

Yet for all that rancor, Johnson signed a new contract with the Cowboys this year. Even he admits that he’s now quite handsomely paid. Johnson signed because he and his wife, Julie, have a new home in Plano and a one-year-old son. He signed because of his partnership in Imperial Investors, an imaginative enterprise that also represents the interests of Johnson’s black teammates Billy Joe DuPree, Too Tall Jones, Benny Barnes, and Preston Pearson, the third-down specialist whom the Cowboys forced into retirement this year. Their corporation includes a commercial janitorial service, a concert production company, a cable television venture, and a speakers’ bureau, with additional holdings in oil properties, fast foods, and thoroughbred racehorses in Kentucky. Johnson wants to construct his base while he still has the public exposure. “People in Dallas have treated me well,” he says, “but they haven’t had the chance to relate to Michael McColly Johnson. All they know is Butch.”

But he also signed the contract with a sense of resignation and despair. He would have dissolved his business interests in Dallas just as quickly as he sold his first business venture, Good Vibes Records and Tapes, when another black teammate and partner, Aaron Kyle, fell into disfavor with the Cowboys’ front office and wound up in Denver. In fact, Johnson went to the practice field one day last spring to tell his teammates good-bye; he thought he, too, was going to Denver. Danny Reeves had been hired by the Broncos’ new owners to succeed Red Miller as head coach, and he made no secret of his desire to take Johnson along. For six weeks the Denver and Dallas front offices negotiated the trade that Johnson had been demanding for years, and they came close to striking a bargain. But in the end, Landry said no.

“We talked around about Butch,” Gil Brandt acknowledges. “It’s very hard to trade somebody who you know is extremely good but has never played as a regular. The other teams say, ‘If he’s not a regular, we can’t give up a high draft choice for him.’ So we hope we’ve satisfied Butch with that new contract, because we feel he’s a very important member of our football team. I liken him to the sixth man in pro basketball, who’s often one of the highest-paid players on the team, even though he’s not a regular. You’re going to see more players in pro football—offensive and defensive—who perform specialized roles as substitutes on first, second, and third downs. And I think you can justify paying those specialists a large salary.”

Johnson interprets it somewhat differently. “They know I’m talented, and they know what I’m worth,” he says, then lowers his voice conspiratorially. “But because of the lack of playing time, the lack of statistics, who else would ever know? If I’m so talented, why ain’t I on the field? And if I go up to Denver and catch eighty passes, that makes the organization here look bad.

“I don’t know the details of the deal Danny offered. Maybe I’d be insulted. But I understand it was a multiple draft choice situation—one player this year and another in 1982 if I start for Denver. Hell, there’s no question I’d have started up there. I know the system, I know what Danny’s looking for, and he’s been pushing for me down here all along. If I go somewhere else, I have to start all over. I’d have to build myself up for the new coach, make the plays for him, establish a new reputation from scratch. Denver was the perfect opportunity for career advancement. That opportunity will never materialize for me again. And I’ll be bitter and resentful about that, I would imagine, for the rest of my life.”

He clenches his jaw and looks away. “So why did I sign? Once I’ve found out they’ve refused to trade me, do I really have a choice? I have tried to get out of here. Last year I told them, ‘Don’t trade me, then. Cut me. Put me on waivers. I’ll take my chances.’ But they’ve got me trapped here. I have no freedom of movement. If anybody in this organization was really concerned about me, really concerned about my career, I’d be in Denver today. But they know that no matter how much I bitch and groan, when I step on that field I’m going to perform. They tolerate my bitching and groaning because they know what I can do for them, and I tolerate my end of the situation because I have to. I don’t necessarily have to like it, but I’m a professional—I’ll play. I’m being paid to play football. And as long as I can play football, I’ll be paid. That’s the bottom line. Like I say in practice: dat’s the fact, Jack.”

Unless he gets hurt, Doug Donley, the second-round draft choice from Ohio State, will be the fourth wide receiver in Dallas this year. A blond six-footer who weighs only 174 pounds, Donley runs the hundred-yard dash in 9.4 seconds. At Columbus his nickname was White Lightning. Donley announced that he intended to break into the Cowboys’ lineup as quickly as Tony Hill did—in his second year—and judging from the raves of the coaches at training camp, he well might. He tossed out one of the more quoted lines in Thousand Oaks when he said he didn’t have “the white man’s disease—no speed.” But he’s not as brash as he sometimes tries to sound. Donley is a quiet small-town kid from Cambridge, Ohio, where his dad is a plumber and his mother runs the Hallmark card shop. And in Dallas he knows what he’s up against.

“I’ve got the speed and the hands,” says the rookie, “but you can’t just run as fast as you can, then catch the ball. There’s a lot more to it than that. These guys are smoother and more deceptive than I am. They’re not breaking any strides going into their routes. I’ve got the steps down on the short routes. But on a fifteen-yard out, for example, they’re running eight steps every time before they make the break. I’m still marking the yardage and trying to remember not to slant the route like we did at State. I feel like I’m having to think too much.”

Donley affects a yellow plastic comb in the hip pocket of his jeans just like players with Afros carry wire rakes. Asked for his personal impression of the veteran wide receivers, the rookie strokes his chin diplomatically, then blushes and erupts in laughter. “I’m used to being a minority at my position,” he says. “The other night we were in a meeting, then went out in the hall for a break. When I looked around there were eight black guys and me. Wait a minute. Guess I’ll go talk to the quarterbacks.”

“The way Roger and Drew would pal around together,” says Danny White, “kind of hurt my feelings. Drew always wanted to be on Roger’s team when we played basketball. I could shoot baskets as well as Roger, and I thought I could throw footballs as well, too. But it was always that way. Drew and Tony were Staubach’s receivers. Butch and Jay Saldi [the backup tight end and the utility wide receiver] were mine. When we’d work out in the offseason, Roger would say, ‘Okay, I’ve got Drew and Tony, you’ve got Butch and Jay—let’s have a contest.’ I never said anything. Still . . .

“Butch and Jay and I have always been real tight. We started out with the Cowboys the same year and worked on the second team together. When Roger retired, Butch and Jay were thrilled, because they figured they’d catch more passes. And they did. Both had their best stats ever last year—because we work together so well. But now that I’m the starting quarterback, there starts to be a conflict. I can’t afford myself the luxury of throwing to my best friend because he’s my best friend. I don’t want Drew and Tony to think I’m not throwing to them because Butch and Jay are my friends. And I don’t want Butch and Jay to think I’m not throwing to them because I’m overcompensating for that. It all gets very . . .” The quarterback shakes his head.

Last year White’s 28 touchdown passes broke Staubach’s single-season record, and if he hadn’t thrown 25 interceptions, his stats might have ranked first in the league instead of ninth. He completed 59.6 per cent of his passes; during their tenures with the Cowboys, Staubach, Craig Morton, and Don Meredith had completion averages of 57.0, 52.4, and 50.7 per cent, respectively. It began to seem that White’s success would be the beginning of the end for Drew Pearson. Hill’s catches during the first half of the season outstripped Pearson’s by nearly three to one, and while the gap narrowed quickly toward the end, their stats tell the story. Hill scored eight touchdowns in the regular season on 60 catches, with an average gain of 17.6 yards. Pearson scored six times on 43 and averaged 13.2. At one point Pearson told reporters that if the Cowboys had no further use for him, other teams in the NFL might.

The organization’s only questions about White concerned his capabilities under the pressure of the two-minute drill—the come-from-behind frenzies that characterized Staubach’s career. In the second round of the play-offs the Cowboys flew to Atlanta to play a team that had won nine games in a row; the Falcons were the hottest team in the league. Tony Hill was hurt, and in the first half White lost an important touchdown even though Butch Johnson beat the Falcons on a post route and caught the ball. Two steps after the end-zone catch, a Falcon defender got a hand on the ball and pried it from Johnson’s grasp, and the officials, in a poor call, ruled the pass incomplete. With 3:40 left in the game, the Falcons led 27–17. Under the gun, White drove the Cowboys in for the two necessary touchdowns, and each time the scoring pass went to Drew Pearson.

Pearson describes the second of those catches, which came with 42 seconds left: “Even at this stage, Danny reads defenses better than Roger ever did. He anticipates better, because he has to. Don’t get me wrong—Danny has a strong arm—but I don’t think I’ve seen anybody who could throw as hard as Roger. Maybe Terry Bradshaw. If the defense had me covered, Roger just blew it past them. Danny goes to the open man. He doesn’t try to force the ball.

“Danny impressed me all last season with his composure. In that last drive against Atlanta, it was wild out there. The crowd was yelling for them to stop us, and the Falcons were making so many changes, blitzing linebackers like crazy. That clock was right in front of Danny. But he’d kneel down there in the huddle and stipulate to every receiver under what circumstance he’d be coming to him. That’s poise. When we broke the huddle, all we had to do was look for what would make us the primary receiver. I wasn’t supposed to catch the ball on that last play. The call set me in motion, and I felt the cornerback coming up, so I gave him a couple of quick steps and broke inside. When I looked back, Danny had already released the ball. And he was staring at me. This is split-second stuff, but I felt like I was staggering around trying to find it. If Roger had thrown that pass, I never would have seen it. But Danny lofts the ball. By putting that air under it, he gave me the chance to look, react, and make the catch.”

He cleans his sunglasses with the tail of his velour shirt. “At camp last year they were playing games with me, using Butch Johnson. I wound up having to find out my own way that I was in no position of competing for my job as a starter. Then I got off to a slow start. They weren’t using me the way I thought I should be used, and I heard the talk. A lot of speculation that I couldn’t catch passes from Danny like I had from Roger, that Danny couldn’t hit me on the routes like Roger had. ‘Pearson’s getting old.’ ‘Maybe he’s washed up.’ The Atlanta game eliminated that shit.”

The edge of belligerence in his voice softens. “Last year was hard on me, too, because my dad was dying. I was pressing to do it all over again for him. I wanted to get to the Super Bowl one last time before Dad passed.”

Pearson balances the death of the New Jersey man last November with the Cowboys’ failure against the Eagles in January. “Dad didn’t make it,” he says simply. “And neither did we.”

In this year’s third exhibition game, against Houston, rookie Doug Donley finally got his chance. Though he dazzled the coaches before the veterans reported, since then a torn groin muscle had kept him from even working out. Two days after the Houston game Tom Landry was to trim the Cowboys’ roster to the final 45-man limit, and while it was clear the Cowboys wouldn’t cut a second-round draft choice, a trade seemed a definite possibility. Or would the rookie languish for a year in the purgatory of injured reserve?

Donley wasn’t thinking about that, of course, when his big moment came in the second quarter. Danny White lofted a long pass toward him; Donley feinted left, stutter-stepped, and turned the cornerback completely around. He beat the Oiler badly. But there was plenty of time for those considerations to flash through Donley’s mind as he made the outside move and looked for the ball. It was coming down short, toward his inside shoulder. Nearing the goal line, he pivoted and backpedaled. The pad of the new Texas Stadium AstroTurf was so soft that the footing was almost spongy. He lost his balance and began to stumble. His shot at glory contained the risk of a spectacular muff: imagine falling out of a chair while reaching to the side to catch an object falling faster. Donley fought the catch, stayed with it, and made it. His first reception as a pro was a 33-yard touchdown.

The veteran wide receivers led the swarm of congratulators. Gimme five, Lightnin’. But later on in the game, when Donley made his second pro catch for an eighteen-yard touchdown, they kept their distance. They exchanged glances and looked nervous.

But one hot night from a rookie won’t disrupt the Dallas way of doing things. The surprise winner of the pre-season competition was Butch Johnson. He came to camp with a hard belly, twelve pounds under his previous playing weight of 192, and he seemed to have gained that critical step or two in speed. Even Landry acknowledges that he and Ron Springs were the two best players in camp. Most important, Johnson was the only wide receiver who stayed healthy. He made the most of his opportunity with big pre-season games against two of the league’s best teams, Pittsburgh and Houston. He unveiled a new Elvislike spiking gyration that reporters dubbed the “California Quake.” And, for the time being, he’s changed his tune. No longer the team’s self-appointed controversial player, he quietly told reporters after the Houston game, “It’s been years, literally, since I played two whole games back to back.” Asked if he had won the job, he bummed a cigarette and hiked his eyebrows. “Wouldn’t you say I have the inside track?”

Across the room, Landry agreed—to a point. “Butch will start the league opener against the Redskins. After that, we’ll see. It’s our policy that starters don’t lose their jobs through injury. Tony will get the chance to play back into condition.”

In California, Tony Hill had been having acupuncture treatments. Just as he was getting over the hamstring, he pulled a groin muscle. And he enters the season as the only wide receiver with an unsettled contract grievance. Still, he’s having none of this talk about his imminent demise. “Hey, people kinda forget when you ain’t been around,” he says. “I’ve led this team in receiving the last three years. These muscle pulls are very minor injuries, and my shoulder’s sound now for the first time in my career. As for the compensation, I’m a football player—that’s what my agent’s for. If Mike Trope can’t get me what I need, I’ll get another agent. But before this year’s over, the fans are gonna see a new and even better Tony Hill. Just watch.”

Drew Pearson made his appearance after the Oilers game wearing a red shirt and a black leather vest. Though he sat out the game, the writers rushed toward him. He had been angry enough about his contract that Brandt had feared he might actually walk out. Brandt had made the breakthrough offer to Pearson’s attorney the morning before the game. While Pearson didn’t get nearly as much as he wanted, he signed for a series of three escalating raises that, on paper, will enrich him by more than $100,000. The question is, does he have three more years in him? Is his starting position as secure as the Cowboys have led him to believe? After all, Pearson’s pre-season injury was a concussion, and he has to remember that Roger Staubach, for one, retired earlier than he wanted to because of the neurological danger of too many knockout blows. Management will just have to wait and see if the carrot it’s waving in front of Pearson’s nose will do the job.

As Pearson stretched out in his chair, a reporter asked with thinly veiled hostility if the receiver can get down to the business of catching passes, now that he has made his fortune. When Pearson grinned, his lip curled slightly with characteristic, bemused arrogance. “I’m always ready to play,” he shot back. “Now I can play with a smile.”

How to Catch a Pass

By three masters of the art.

Drew Pearson on the Inside Route

“As you come off the line, you’re reading the defense to see where those backs will be. The abruptness of your stop-and-turn buys you time and room to maneuver. By then, the ball’s already in the air, a bullet pass. Since most quarterbacks are right-handed, it’s coming in a counterclockwise spiral. You know roughly where your center of gravity is—somewhere between your chest and groin, depending on how much your knees are flexed. If the ball comes in lower than that center of gravity, you position your hands with the fingers down, thumbs out. If it’s high, the thumbs are in, fingers up.

“Sometimes when a quarterback throws low, the ball noses down and puts a wobble on the spiral. It doesn’t exactly break like a baseball curve, but it can tail away in one direction or the other. A high pass tends to take off and sail, so you have to be ready to jump. This route is associated with the expression ‘hearing footsteps.’ Essentially, you’re standing still with your back turned to a player who is coming at you full speed and helmet first. You have to shut that out. There’s no great secret to this catch. You make your move and look for the ball. You concentrate.’’

Butch Johnson on the Sideline Route

“The object is to drive the cornerback as deep as you possibly can. That means you can’t fool around with a stutter-step. Without slowing down, you explode out of the break. The throw is the most difficult in football. It’s long, hard, and straight—like a shortstop’s throw out of the hole to first base.

“The play requires constant practice because the timing is so important. It’s the quarterback’s responsibility to make sure you catch the ball in bounds. You look for the ball, not the chalk stripe.

“Ideally, the ball should come in low and outside. If it’s high and inside, you have to be ready to make the contortion and the off-balance catch. Receivers are right-handed or left-handed like everybody else, and most of them position their hands differently for right or left sideline routes. Whatever’s comfortable—but try to keep your arms low. Otherwise, they obstruct your view of the ball. You try to make this or any other catch with your hands alone. You don’t want it to get in against your pads or body if you can help it. You’ve got to have control of the ball before you step out of bounds, and you don’t want to leave the officials any room for doubt.’’

Tony Hill on the Post Route

“The most important thing is to position yourself where you have a free run at the ball. If you’re bouncing off the defensive back or trying to get around him, your chances of making the catch are pretty slim. You have to beat your man first. Then you worry about the ball.

“Outfielders talk about ‘judging’ a fly ball. It’s a sense acquired from endless repetition—that’s why they shag so many flies at practice and before a game. Catching a deep pass is pretty much the same. You look at the ball once and chart a mental map of where it’s going. When you look up again, you’re hoping you were right.

“In those last seconds before the catch, you cover the ground with your legs, not your arms. The more you extend your arms, the less cushion you have in your hands. You don’t jump unless it’s absolutely necessary. If you’re in the air, you’re giving the back time to catch up, and you’re more likely to get hurt. A well-thrown ball will nose up slightly even as it’s falling. That means you can’t catch it on the point with your fingers. The contact point will be the fullest, fattest part of the ball. You form a cradle with your hands and gently pull that baby in.’’

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Irving

- Dallas