Aside from their shared passion for heroes of the civil rights movement and unexplored music history, the thing Texas artists Tim Kerr and Robert Hodge have most in common is Russel Gonzalez. A gregarious music producer who also goes by the professional moniker “the ARE,” Gonzalez has orchestrated a collaboration between Hodge and Kerr in the vein of the Basquiat-Warhol partnership of the 1980s.

Gonzalez is hardwired to stay alert for promotable happenings, and the idea to pair up Hodge and Kerr came after he saw paintings by the two artists side by side. It wasn’t just that the works used different techniques to speak to similar themes; Gonzalez also recognized that certain aspects of the artist’s perspectives mirrored the legendary Basquiat-Warhol collaboration. Most obviously, they were born a generation apart—one white, one Black.

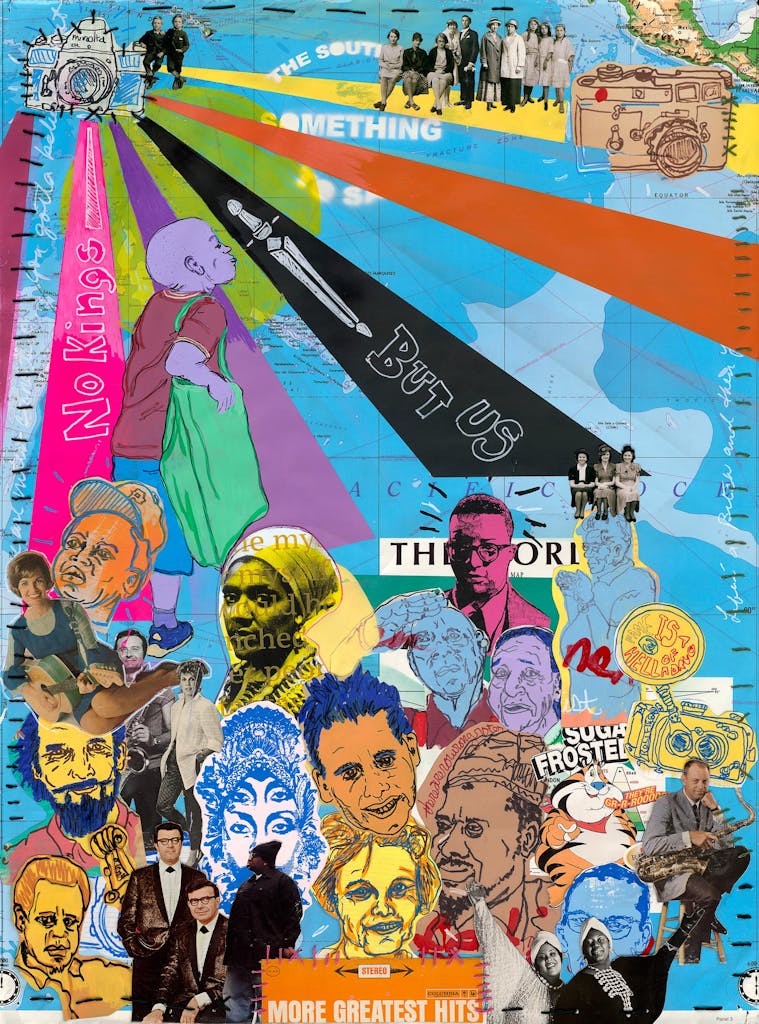

Hodge and Kerr have created about forty paintings together for “No Kings But Us,” a pair of pop-up exhibitions Gonzalez has promoted like one of the concert tours for the nineties hip-hop group K-Otix, which he cofounded and fronted. (He later produced songs for a slew of big-name talents, including Earth, Wind & Fire; Keyshia Cole; Lil’ Kim; LL Cool J; and Nicki Minaj.)

Gonzalez likened his Hodge-Kerr project to creating an album. “All three of us have a music background, so we’re kind of speaking the same language,” he said. They kicked things off with a small preview show the first weekend in May at the Marfa Open Gallery, and the main event is May 20–June 4 at the University of Houston’s Blaffer Art Museum.

Scoring the Blaffer space was a coup for a show organized by a guy with no curatorial credentials. But Hodge’s name carries weight, and Gonzalez’s enthusiasm is infectious. When Gonzalez pitched the idea to Blaffer director Steven Matijcio, he coaxed, “We’re the artists. We need you to be our Sony.”

“Can we be Def Jam?” Matijcio joked.

“You can be whatever you want!” Gonzalez said. “We want to make this show spectacular, like an event, not just a quiet thing. We want a line around the building.” Matijcio saw “No Kings But Us” as a harmless experiment that could bring a whole new demographic into the museum. Gonzalez envisioned it as a one-weekend deal; Matijcio granted him two.

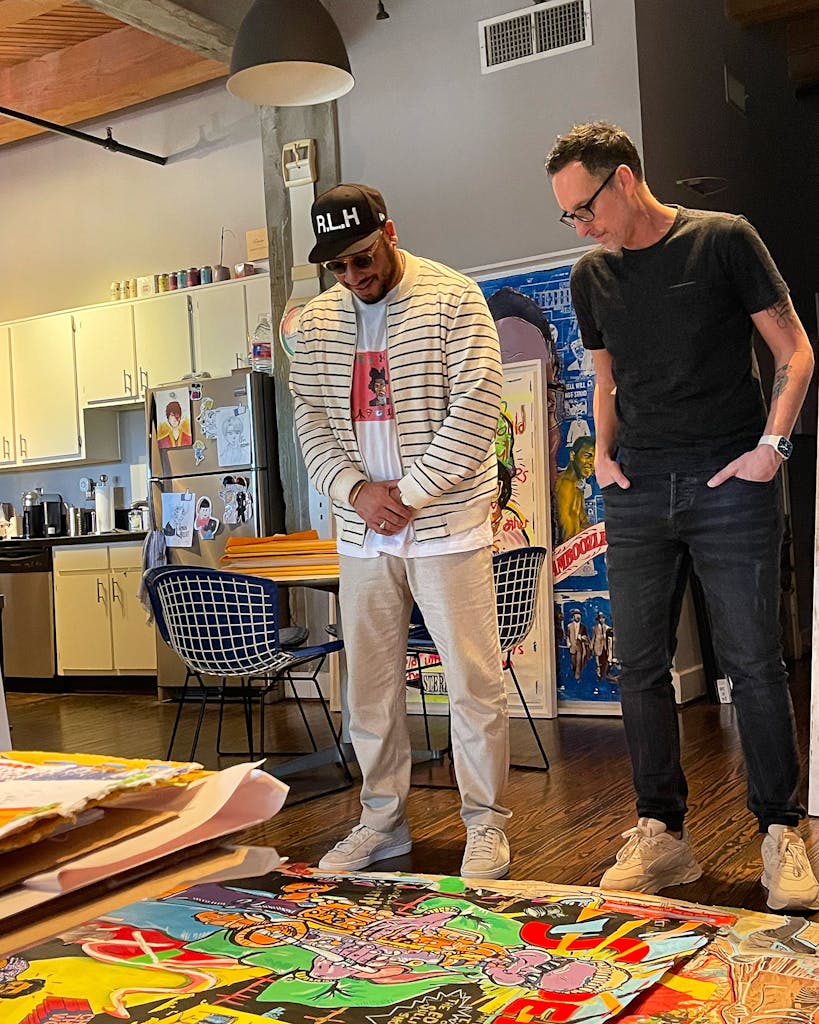

Gonzalez gave me a sneak preview in April at Houston’s Dakota Lofts, first leading me through the lobby he turned into an informal gallery since becoming the building’s manager a few years ago. Hodge was the first artist he invited to show work there. A tenant who knew Kerr suggested adding him to the mix, and after Gonzalez met Kerr, the wheels began turning. Paintings made individually by both artists are still on display in the lobby, but an “art explosion,” as Gonzalez called it, filled his 1,400-square-foot apartment.

Gonzalez’s place is neatly furnished with midcentury furniture, and his walls are densely hung with art he has collected. But on this day, dozens of colorful, chaotic paintings also crowded the open living-dining-kitchen area. We picked our way across the floor through piles of big, unframed pieces, also avoiding framed works that leaned against the sofa and walls. Small canvases hung from a couple of rolling racks near the patio doors. Manila envelopes stuffed with exhibition posters, many destined to be wheat-pasted on building facades and utility poles—an unusual bit of analog marketing for an art exhibition—were stacked on the dining table. About the only clear surface was the kitchen island, which Gonzalez said has been his temporary workshop for mounting and framing the paintings, which he taught himself to do. “I’ve really put a lot of blood, sweat, and tears into it,” he said, cheerfully.

Hodge and Kerr knew of each other but didn’t meet until Gonzalez brought them together. Unlike Basquiat and Warhol, who both circulated in New York’s eighties art world, Hodge and Kerr live 165 miles apart—a distance that’s even further culturally, considering the two types of Texans they represent. Kerr clings to a grungy, “Keep Austin Weird” spirit he helped create, while Hodge is a hip-hop-influenced Houston sophisticate.

Stylistically, Kerr’s work is loose and improvisational, of the moment. He doesn’t want to be categorized as anything other than a “self-expressionist,” but for folks who want to know, he’s both an indie music legend and a visual artist who earned his photography degree at UT in the seventies, studying with the great American street photographer Gary Winogrand. He’s in the Austin Music Hall of Fame as the cofounder and leader of several influential eighties Texas DIY punk bands, including Bad Mutha Goose, the Big Boys, and Poison 13. He’s done funk, too. Now he has an all-acoustic folk duo (with Jerry Hagins) called Up Around the Sun. “They’re calling us Windham hillbilly, which I think is pretty hilarious,” he told me in his deep drawl during a phone interview.

Kerr always created his own visuals for album covers and posters, and he has painted skateboards and murals around the world for the past twenty years or so, by popular demand—not because he planned it that way. If you know his Unsung Pioneers of Austin Music mural at the corner of East Ninth and Red River Streets in Austin, you also know he adds a lot of text to introduce the heroes he paints, and he often signs his works “Your Name Here,” hoping the signature inspires viewers to create whatever moves them too. Art shouldn’t just be about visual stimulation, he said. “You need to educate people a little bit.”

Hodge has a similarly broad practice, but he uses the formal name for it: multidisciplinary. His work is meticulously planned and detailed, and he has built his career just as purposefully, starting as a teenager at Houston’s High School for the Performing and Visual Arts, then studying at Pratt and the Atlanta College of Art. He found his best mojo back home as a member of the lively community of artists and curators at Project Row Houses. His mixed-media works, many of which consider history from an African American perspective, often hang now in big museums. (One of his large painted assemblages is up currently in “The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century” at the Baltimore Museum of Art.) He’s produced vinyl albums in conjunction with some of his shows; that’s how he met Gonzalez. He mentors young muralists. He is jamming this month to finish a new suite of paintings exploring critical race theory for his next solo show at Houston’s David Shelton Gallery, which opens May 26.

Hodge and Kerr began sharing canvases long-distance last August, with Gonzalez ferrying the work between Austin and Houston. The artists got a better rhythm going early this year when Gonzalez set them up for two weeks at Houston’s Hardy & Nance Studios, although they still had some learning to do about each other, starting with their personal symbols. For example, Kerr initially scratched his head over Hodge’s frequent use of a collaged, vintage “Stereo” label, because he had long related that word to a skateboard brand. For Hodge it’s about diverse voices coming from different places. Then there were questions about what they could paint over, cut up, or otherwise deface in the shared work. “The good thing was that we’re not that precious about what we’re doing,” Kerr told me. “I’m not ‘artiste’ about it, and he’s not really, either.”

The result is an exuberant mash-up of images and text. Some of the paintings are done on vintage schoolroom maps, and some have hand-stitched elements. It’s cohesive enough to look like the work of one artist, which is more than you could say about the Basquiat-Warhol collaborations. Kerr’s minimal but expressive line drawings, which he fills in with flat acrylic colors, mingle effortlessly with Hodge’s layers of paint and collaged, screen printed images. Their bright palettes are compatible, too.

Hodge stopped by Gonzalez’s apartment while I was there. “I’ve collaborated before, but on single pieces—never a show this big,” he said. “I had to figure out how to add value without taking over.”

That thought apparently didn’t stick with Hodge and Kerr’s painting of Rahsaan Roland Kirk, a blind musical genius active from the 1950s to the 1970s. As we examined it, Hodge explained that Kirk played multiple saxophones and flutes at once. Kerr had started the painting, sending Hodge a simple composition on paper that showed Kirk against a red background, alongside text that read “Celebrate Your Time Here.” Gonzalez had a picture of that version on his phone. The written sentiment struck me as Hallmarkish; was it a joke or a prompt Kerr knew Hodge would paint over? It doesn’t matter now. Hodge, who dove into research about Kirk, indeed turned up the volume. He ended up covering Kerr’s initial text and most of the red background with a thick layer of black and busying up the composition to mimic a Superman comic cover. He added smaller figures of Charles Mingus on bass and Roy Haynes on drums to commemorate a landmark performance on The Ed Sullivan Show in which Kirk promised listeners “true Black music.”

The artists didn’t pass a lot of their canvases back and forth more than once, but it looks to me like Kerr couldn’t resist adding some final, scribbly touches to the Kirk piece. Either that or Hodge was trying to loosen up, Kerr-style. Either way, Hodge’s crisp painting has been “defaced” with an acrylic pen. At the top it reads, “It ain’t Superman (self).” Other comments have been scrawled on, too, along with the musicians’ names, which is something Hodge typically doesn’t do in his work. I found a clip of the Sullivan Show performance on YouTube. That cacophonous, joyful free jazz must have blown some minds in 1971. Looking at the painting, you can almost hear it.