The Town

In some ways Mullin has scarcely changed in a century. The outlying terrain is pretty—Hill Country changing into mesquite savannah, rich in lore of Comanche, German settlers, circuit-riding preachers. The original hamlet, Williams Ranch, had stores, saloons, a hotel, a mill, a blacksmith shop, and 250 inhabitants in the 1880s; it was considered for the site of the University of Texas. But it was on its way to being a ghost town by 1892, and the community migrated four miles north, becoming Mullin, which today has a population of 214. People choose to live in Mullin, but not many work there. They commute to jobs in Brownwood, 24 miles away, and perhaps own a few hundred acres outside town that they farm and ranch in their spare time. Many streets are unpaved. Driving through the town, one sees old-timers whittling on porches and a backyard fence decorated with remains of catfish heads. Main Street in Mullin is itself a skeletal remain: a post office, a lumberyard, a domino parlor, the Downtown Grocery and the Downtown Auto Parts, and storefront shells that the wind blows through.

But the forlorn appearance is deceptive. Mullin is different from country towns that look much the same; it has quietly become a refuge for casualties of a new and hard-bitten Texas wrenched from the old. Years ago, many residents found work at an institutional home for foster children in nearby Goldthwaite. Later, a few started their own facilities and took on the upbringing of children, most from the cities, who were left in dire straits by parental illness, poverty, or abuse. Other families in Mullin obtained a license and made room in their private homes for three or four wards of the state. Foster parents are compensated—roughly $30 a day per child—and the need for them is unquestioned. About one fifth of the 155 students in Mullin’s school system today were placed in the community by the courts. One boy at Mullin High came to town when, not yet in his teens, he was caught stealing food for himself and his abandoned siblings. Another belonged to an inner-city gang. Another lived in a junked car. Another was put forth as a back-alley fighter by adults who bet on him as if he were a gamecock.

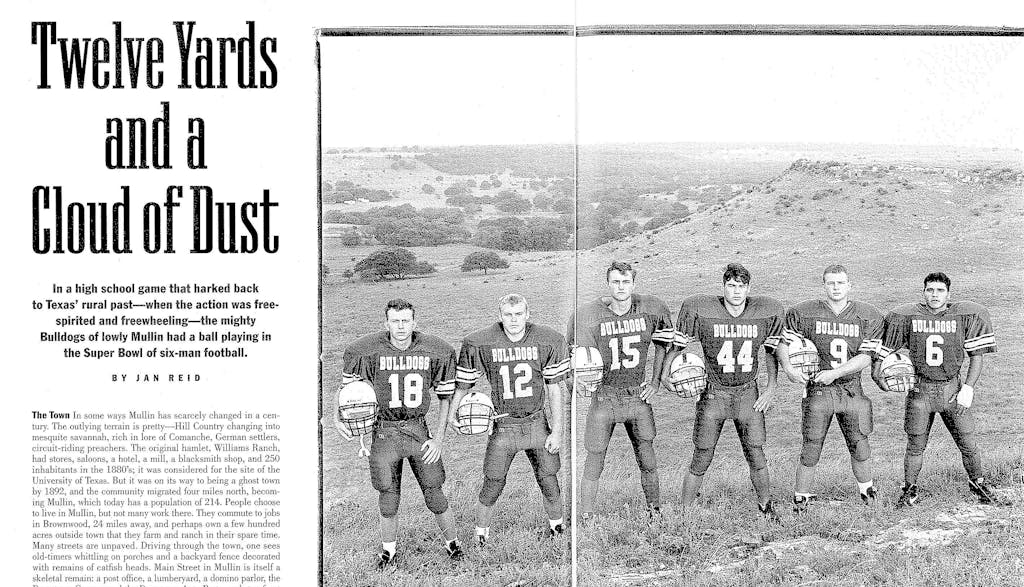

For educators, the challenge of maintaining a cohesive and congenial learning environment with a student body of such newcomers and the local youths whose parents and grandparents grew up in Mullin is daunting, to say the least. Mullin has done it by emphasizing an often condemned mainstay of the old Texas—high school football. Because the high school has just 59 students, the Bulldogs compete in the exotic variant of six-man football, but the town has never known anything else. Over the past four years, a core of talent evenly divided between native and foster kids has turned Mullin into a state power. In preseason polls Mullin was rated number one in the nation. In mid-September the Mullin Bulldogs were going up against a Colorado team in a contest ballyhooed as the Super Bowl of six-man football. The Bulldogs’ success on the field has given the whole town a needed boost of morale and pride. Twenty-nine boys enrolled at Mullin High this fall. All but a couple either play football or help the team as a manager. Two seniors play on the junior varsity, but still they play.

The Team

About three o’clock every afternoon on the south side of town, some horses come walking and nodding out of a pasture on the way to a water trough. The heat was surreal this September day. Dust devils sucked grit from a rodeo arena and whirled off into a glaring sky. Passing along a fence, the horses lowered their ears against the stinging gusts and watched the boys emerge from the yellow schoolhouse and jog onto the Mullin field. It was a scene being played out that day and hour in countless small towns. But the Bulldogs demonstrated at once that their high school sport is different. Everybody grabbed a ball. They set their helmets on the ground and started throwing passes, running exaggerated routes, ragging each other about their arms and drops. They loosened up as if they were out for a game of touch.

Six-man players compete on an eighty-yard field. Like eleven-man players, they have four snaps to make a first down, but they have to gain fifteen yards, not ten, to move the chains. Everybody is an eligible pass receiver. Six-man is a celebration of offense and scoring; evenly matched teams regularly put eighty to a hundred points on the board. The value of point-after conversions is reversed; successful kicks are worth two points, because they’re so easily blocked. The hitting can be ferocious because most tackles are made in the open field. But if the tackler misses, chances are, the ball carrier is gone. It’s a game of speed, not brawn.

The Bulldogs’ head coach, a portly part-time rancher named Leonard Buffe, strolled onto the field wearing a T-shirt, a cap, and blue jeans. “Kids want discipline,” he remarked to me but later added with a smile, “If I didn’t give ’em a hard time, they wouldn’t know I was here.” The players seemed to respect certain limits but felt free to imitate his drawling expressions and touch him on the shoulder as they trotted back to the huddle. “If that ain’t embarrassing,” he chided a receiver in a passing drill. “That’s pitiful. There’s the ball layin’ on the ground!” Last year two youths skipped a workout to go fishing. Coach Buffe made them suit up for the next practice and sit on the bench, holding their fishing poles. The coach and his assistant Ronny Crumpton are helped out at games and practice by a voluble old-timer, A.R. Whisenhunt, who for many years was the Mullin superintendent. Mr. Whiz, as everyone calls him, came out of retirement last year to be the campus disciplinarian. Every week during football season, he writes a poem and posts it in the hall at the school. Of Richland Springs: “The Coyotes tried, done their best/Too much Bulldogs, they failed the test/At the half it was forty to nothing/And how those Coyotes were huffin’ and puffin’.”

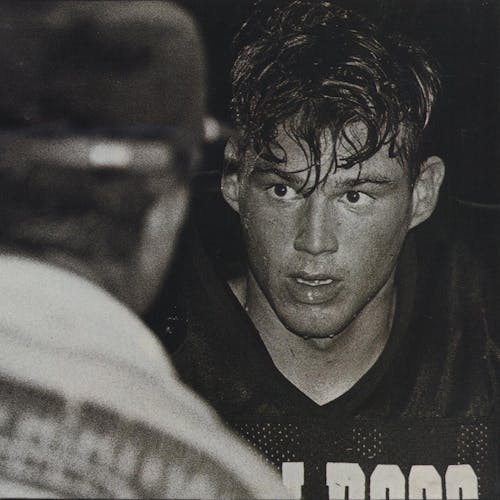

Two of Mullin’s senior stars were easy to pick out. The most vocal and assertive of the team’s foster kids, Petey Salaiz is a muscular Hispanic youth whom Texas Football magazine this year proclaimed “the Earl Campbell of six-man football.” Petey stands just five-eight and weighs 175 pounds, but in his all-state junior season he rushed for 3,226 yards, averaged 12 yards a carry, passed for 700 yards, and scored 71 touchdowns. Petey’s counterpoint among the native youths is Charlie Smith, who has the tanned and chiseled look of a Gary Cooper. At six-two and 190 pounds, Charlie plays defensive end, quarterback, and fullback and was second-team all-state a year ago. But Charlie is sure to get criticized no matter what he does; his dad and other male kin keep up a loud running commentary every Friday night. In the season opener, a 46-0 rout of Richland Springs, Charlie was the star of the game. But when he grabbed a runner by the shoulder pads and slammed him to the ground, his dad’s voice boomed, “Might work a little better if you was to hit him low!” Charlie will probably carry on this family tradition if he ever has a son. For now he keeps up the chatter. His baritone goad has become a sort of team mantra: “Come on, girls.”

The Bulldogs were on the field three hours that day. They coped with the heat by turning on a water hose and soaking their heads. One filled up his helmet and held it like a colander, watching rivulets pour through the air holes, then pulled the headgear and cooling bath down over his ears. At the end the players knelt with their arms around each other’s shoulders. Rodney Thomas, a young Baptist preacher who is the team’s volunteer trainer, led them in a prayer. “I know that’s probably illegal,” Coach Buffe said with another grin, as he gathered up balls. The Mullin Bulldogs were the loosest football team I had ever seen. Even in practice, they looked like they were having fun.

Leonard Buffe grew up on a ranch a few miles away. He played six-man well enough in Pottsville to be invited to an annual all-star game. His wife, Linda, now the Mullin High principal, was raised on a nearby ranch. They both attended Tarleton State University in Stephenville. He taught and coached in area schools a few years, got out of it for a decade, and just ranched; then five years ago he took the job in Mullin, whose Bulldogs had just gone 0-10. His first varsity team didn’t fare much better, but the eighth-graders, who included Petey and Charlie, won every game—on defense they allowed only one first down all season. They won seven games as varsity freshmen, eight as sophomores, and last year they reeled off twelve straight wins before losing to Milford 32-30 in the state quarterfinals.

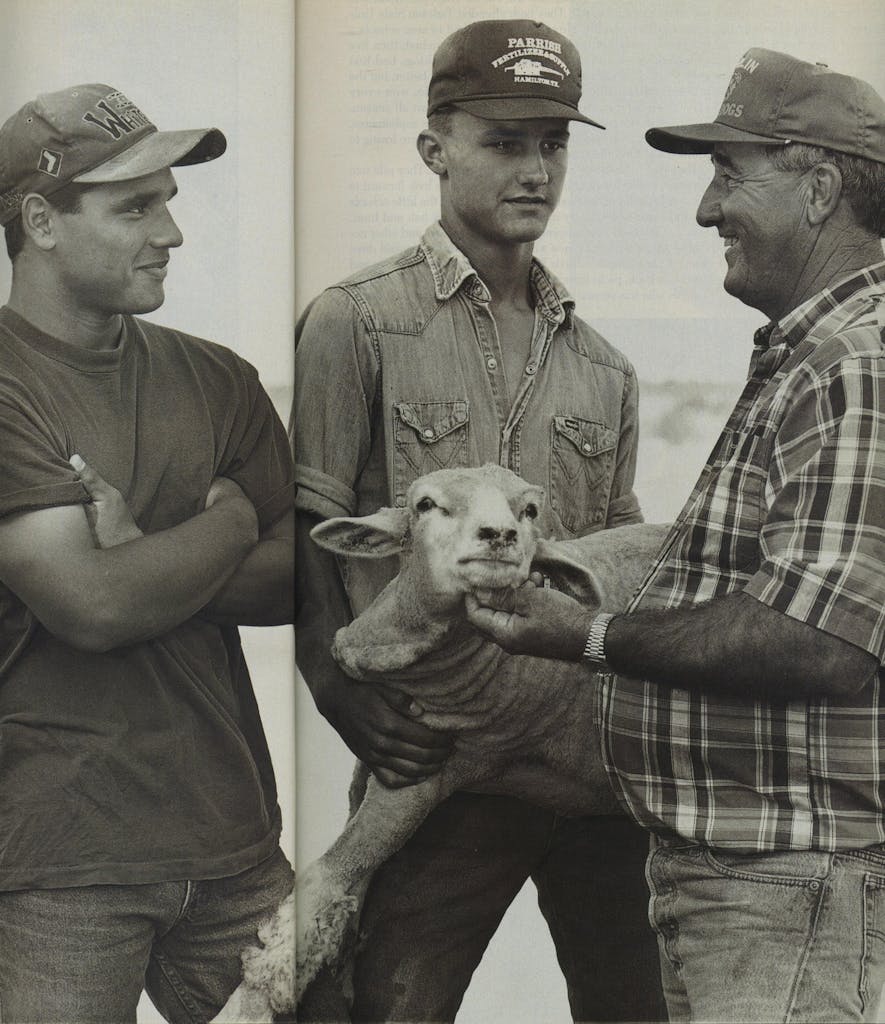

They stay in shape by hauling hay in the summer. They pile into cars and cruise the drag in Brownwood, and they look forward to the first Saturday of the month, when kids from all the little schools around come to a country dance in Priddy. They fish and hunt. Charlie’s boyhood was enlivened by Dallas Cowboys and other notables who leased the place where his dad worked for fall dove hunts. Charlie’s cousin Travis Wilson, a utility offensive player and defensive back, picks up spending money as a rodeo clown. Bobby Teague, who was second-team all-state as a nose guard, is also the team’s leading receiver—though his vision is so poor that all he can do is look for a dark blur in the lights. Landon Buffe, a steady senior offensive and defensive back, expects to follow his parents and older brother to Tarleton State, and he has a younger sister at Mullin High. This year the household has another member—Petey Salaiz. The boys do chores together after practice, feeding the sheep and goats.

Petey and his two sisters arrived in Mullin when he was in the sixth grade. “I thought it was weird, and I didn’t like football then,” he told me. “I didn’t like anything about it.” One sister has since graduated and moved away from Mullin. The other, Rita, is a sophomore cheerleader. When Petey turned eighteen, he exercised his legal option to leave the foster home and chose to live with the Buffes, who are not his foster parents—the arrangement is informal. His room in the ranch house is decorated with photographs of his family. Petey is close to his mother, who lives in a larger town a couple of hundred miles away. As the big game with the Colorado team neared, he talked to her several times on the phone, asking her if she still planned to come.

Unless he gets hurt this year, Petey will close out his high school career with about 10,000 yards rushing. I asked him if he studies the moves of the game’s great runners. “Sure,” he said. “I like Emmitt Smith. He makes his own holes. But my favorite is Barry Sanders. He thinks with his feet.”

I wondered if he had thought much beyond school and football.

He smiled and said, “I’d like to be a cop.”

The Booster

Six-man football gets almost none of the sports-page coverage that Texas newspapers lavish on eleven-man teams, and college recruiters decline to scout the players. Since the sport first appeared in Texas in 1938, only one six-man player has made the leap to prominence in college or the NFL—Christoval’s Jack Pardee. Few schools have a band. The stadiums are so small that spectators in the bleachers are outnumbered by folks seated in lawn chairs and on the hoods of pickups. Still, six-man has a cult following in Texas. A well-played six-man game is wild and thrilling to watch, and the isolation and untrumpeted nature of the sport add to its appeal. Six-man is the game of the American heartland village. It’s throwback football, stripped of glitz and delusions of grandeur: Playing the game is its only reward. At least, that is, until somebody thought to promote it.

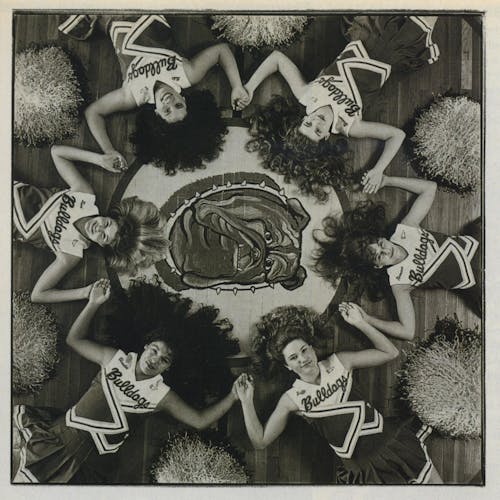

Phil Watts lives eight miles down a dirt road and once lost a car in a flooding creek, but you wouldn’t know it from his shoeshine. In Brownwood he’s an insurance agent and a beaming, handshaking, old-school chamber of commerce booster. Watts also serves on the school board in Mullin; his daughters, Tami and Taffy, are Mullin cheerleaders. Last year Watts bought an FM country radio station in Brownwood called KXYL. Trying to expand his market share, he reached out to rural folks in the listening area with a weekly broadcast of six-man games. The ratings soared.

Naturally, he took an interest when Coach Buffe talked about scheduling a game this year against a top team from Colorado, Weldon Valley. For the game, Watts proposed to fill Brownwood’s stadium with the largest crowd ever at a six-man game. He talked local merchants into guaranteeing enough gate to cover Weldon Valley’s airfare, and on the radio he hyped the game with fever pitch. The number-one and number two rankings of the teams offered trappings of a national championship—make that North American, since the sport is also played in Canada—why, call it Super Bowl Six.

“How many people get to be number one in anything in life?” Watts crooned on his radio station. “Especially if they live in a community of two hundred? This coach from Weldon Valley, he says his team is capable of scoring fifty or sixty points against a team like Mullin. Are these guys gonna come down, as their coach says, and show us a new brand of football?”

The scale of the Brownwood event began to sink in when Governor George W. Bush placed a pleasant call to KXYL that was broadcast at Mullin’s schoolhouse. Colorado’s governor, Roy Romer, followed suit with a nice telegram. The CBS affiliate in Denver sent down a crew to cover not only the game but also the Mullin pep rally. On Friday, September 15, the football players wore neckties to school. Just before the pep rally, they gathered in a classroom with the coaches. “They’re good, they’re quick, they’ve got three all-staters,” Coach Buffe said of the Weldon Valley squad. “They’d like nothing better than to come down here and thrash us. You better be ready to play. And I ain’t gonna lie to you—that crowd’s gonna be loud.” He slid Charlie Smith a grin. “But that’s not all bad. It’ll make it a little bit harder to hear your dad.”

That night, Phil Watts and the game’s sponsors feted both teams with fajitas and another pep rally at the parking lot of a Brownwood shopping center. The booster climbed up on a flatbed trailer and with a broad smile unfurled a large Colorado state flag as Tami, Taffy, and the other Mullin cheerleaders led some yells for the visitors. The adults who made the trip with the Colorado team were ruddy blond farmers, and they were charmed by the show of hospitality. Weldon Valley is a consolidated district that serves three hamlets amid miles of corn and sugar beet fields on the plains east of Denver. There’s nothing much in the town of Weldona but the school, a post office, and a pool hall.

“We’re not like these Texas teams that just line up and try to run over you,” Jeff Durbin, the Colorado coach, told me. “We look for a way to trick you. We’re patient, and if we find a mismatch, we’ll pick you to death.” But as his team worked out the next morning in shorts and helmets on the Mullin field, it was hard to see where that mismatch might lie. In fact, some onlookers feared for the youngsters’ health. Compared with the Bulldogs, the Warriors were tiny, and a few of the reserves looked like they were twelve years old. The Warriors dropped passes and fumbled snaps. Only when they ran wind sprints did any of them look impressive. One could see why the junior quarterback, Shawn Loos, is nicknamed Wheels.

Afterward Durbin carried on amiably for his hosts and the Denver TV crew. “How can anybody possibly stop a great runner like Petey Salaiz? And if you slow him down, why, here comes that big number forty-four. What’s his name? Charlie Smith?”

Wait a minute, someone interjected. This from the guy who had been talking about scoring fifty or sixty points? Durbin’s eyes widened. Who, me?

“Yeah,” Coach Buffe drawled. “That’s what they been sayin’ on the radio.”

Durbin walked off laughing and said, “I want it known that Phil Watts is a liar!”

Weldon Valley rode away in a borrowed Mullin school bus. With friends, Buffe sat in the shade of the concession stand, in need of some peace and quiet. He’s not accustomed to strangers who stick a TV camera six inches from his face without so much as a how-do-you-do. Jimmy Smith—Charlie’s dad—had watched the Warriors’ workout. “If you all lose tonight, I got another boarder for you,” he quipped.

Jimmy’s brother Robert laughed and recalled a time when the rodeo arena was the Mullin football field. “Never will forget one game,” he reminisced. “I saw two players coming, and I was gonna take out both of ’em with a side body block. Well, I missed the first one, and the other come right through me with his knee. I was layin’ there gaspin’ and gaggin’, never gonna breathe again and then I heard my dad. He said, ‘Why, I believe that’s one of them Smith boys.’”

The Game

“I don’t believe it,” said a woman who smiled and stared at the Brownwood stands. She was with the Denver TV crew. “I thought it was all Texas hype.” The cars and pickups had started arriving an hour early, and the folks in caps and cowboy hats were still streaming in. Watts and his sponsoring merchants had set their record—filled to capacity was a stadium that seats 7,800. The crowd included just about the whole town of Mullin, a small group of Coloradans, and folks from Blanket, May, Zephyr, Gustine, Sidney, Richland Springs, Cherokee, and Strawn. The game was more than a showcase of football: It was a show of pride in their way of life.

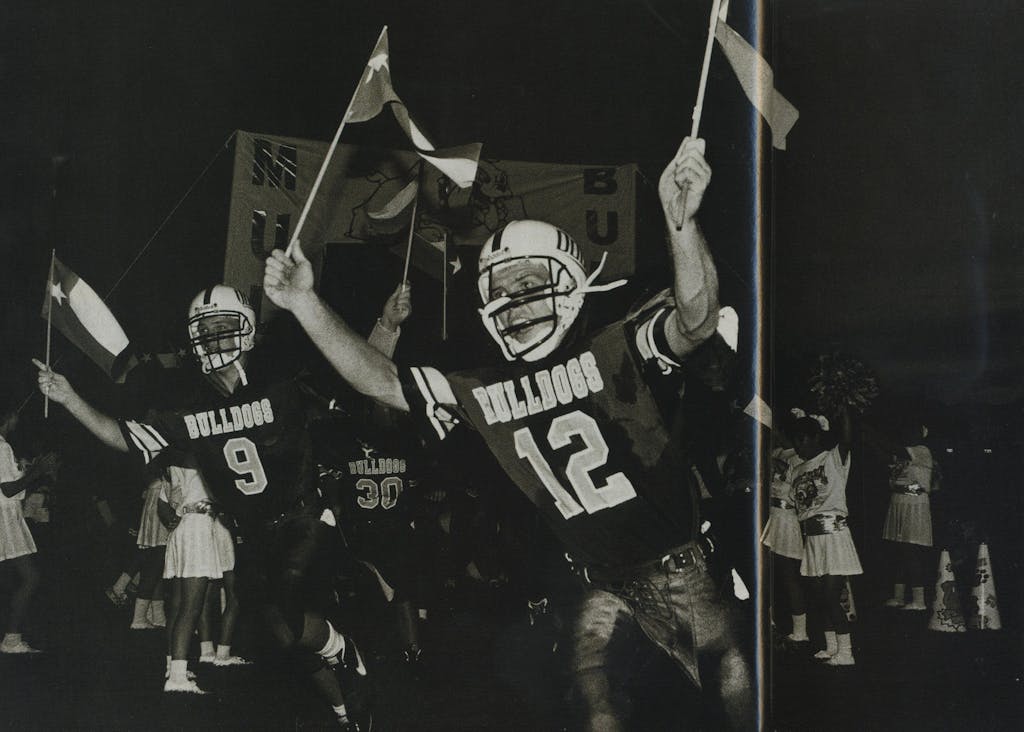

Midweek rains had broken the heat, and the twilight was gorgeous, mauve and pink. Weldon Valley, in white uniforms and pale blue helmets, had taken the field first. Charlie Smith roamed the Mullin locker room as excitement built. “Let’s go, girls,” his voice rose. “It’s show time.” Petey’s mother didn’t get to come. As he and Charlie led the Bulldogs, in their bright purple uniforms, down a ramp, with their fists they raised a sharp, martial drumming on their thigh pads. They ran out through the pep squad’s victory banner, then veered over to the visitors’ bench—not to taunt the Warriors, but to hand each of them a little Texas flag, which of course had something of the same effect.

Two plays after the kickoff, Charlie took the snap, turned, and lobbed a cavalier pitchout to Petey, then joined the herd of blockers. Petey is so short and muscular that in pads, he looks like he must be slow. In fact, he’s very quick with his feet, and in three steps he’s churning full speed. Petey blew past white shirts jolted by the blocking and whooshed half the length of the field with just fifty seconds off the clock. It was a view the Warriors had all night—Petey with his back to them, growing smaller, nothing before him but Bermuda grass and chalk.

Seconds later, Weldon Valley running back Travis Shaver threw a pass that Travis Wilson, the sometime rodeo clown, wrestled away from a leaping receiver. Mullin and the crowd smelled blood. But then Charlie dropped back to pass, tried to spin out of a sack, and lost a fumble. In the ensuing drive, Shawn Loos, who runs with relaxed elegance, popped open for 19 yards, and the Warriors cruised right in to tie it up. The game turned into the frantic shootout the booster had promised. The offenses traded scores with the tempo of fast-break basketball. Mullin’s attack was true-blue Texas—power sweeps and crossbucks, 12 yards and a cloud of dust. The Coloradans answered with slick ball-handling and daredevil laterals. Early in the second quarter, Charlie powered across from the one. On the kickoff, Loos caught the ball in the end zone, started out slowly, saw a gap in the Bulldogs’ coverage, shifted to high gear, juked to his right, and ran 82 yards without a hand laid on him.

That runback, which tied the game 18-18, changed its chemistry. One could see the Warriors gaining confidence, maybe even a few pounds, while exasperated looks shot back and forth along the Mullin bench. Following another exchange of scores, Weldon Valley faked a kick, threw a pass, and took its first lead of the night, 25-24. Mullin gave up another fumble, Weldon Valley rolled in for another score, and they converted again with a pass off a fake kick. Mullin roared the length of the field in just 49 seconds. Charlie scrambled as time ran out, threw deep and long, and Landon Buffe made a fine leaping catch. But the Bulldogs failed to convert. With the crowd subdued, they ran up the ramp trailing 32-30.

Jeff Durbin presided over a locker room of sky-high players.

“Who the hell wants it more?” the Warriors’ coach bellowed.

“We do!”

Cowed by Loos’s runbacks, the Bulldogs squib-kicked throughout the second half, which gave the Warriors a shorter field of play. Loos would line up at quarterback with all five teammates on the line of scrimmage; the Bulldogs couldn’t read the blur of crisscrossing fake reverses, and they couldn’t contain the option pitches. Coach Buffe lost his calm once, grabbing a defensive end’s jersey and yelling at his assistant, “Can we get somebody out there who’ll turn them in?”

Petey finished the night with 300 yards rushing and five touchdowns—including runs of 73, 44, and 42 yards. But the game’s pivotal moment came with six minutes left. Petey carried on a crucial fourth down with 6 yards to go, and three tacklers hung on and dragged him down 1 yard short. As time ran out, the Bulldogs were tearing down the field, trying to score again, but came up short. They were outplayed and beaten, 58-44. At the gun, Charlie tore off his helmet and bit out a curse at the starlit sky.

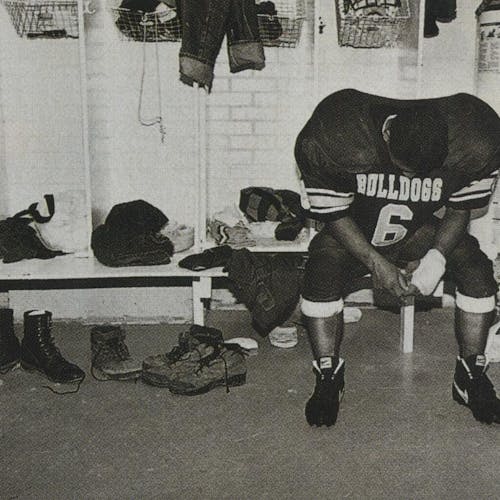

The Bulldogs shook a few hands and left the joyous tourists brandishing their national championship trophy, courtesy of Underwood’s barbecue place. They had thought they would take whatever happened in stride. They had told themselves it was just a non-district game. But then it had never really occurred to them that they might lose. They kept hearing the reputed words of that coach: fifty or sixty points against a team like Mullin. They feared they had embarrassed themselves in front of all those people. “That’s a good ball team,” said a drained Coach Buffe, walking up the ramp. “Petey played a good game, but we didn’t give him much help.” As the crowd thinned out, some of the youths emerged from the field house in street clothes with their hair wet. Linda Buffe called the name of one of the seniors who plays on the junior varsity. He has traveled a difficult road just to have a chance to graduate from high school. She wanted to console him and called his name again. He heard her, but he set his jaw and walked on. Watching her expression, I thought of something she had said that morning while making breakfast for the teenagers who live in her house: “We’re just country people. Children is all we really know.”

The sun came up bright the next morning. Out in the countryside doves were dodging hunters, and folks were fishing the stock tanks. Coach Buffe had pulled out of Brownwood early in a Mullin school bus, swapping yarns with his new Colorado friends, whom he had to drive to DFW Airport. Rodney Thomas, the Bulldogs’ volunteer trainer, preached his sermon, and A. R. Whisenhunt began to give some thought to his poem. Life in Mullin would get back to normal. With winning comes losing. Maybe the Bulldogs had learned some things about themselves that would help them down the road. Those were the easy rationales. Easy and empty. The spotlight was seductive, and then it proved to be devilish to escape. This one hurt.

- More About:

- Sports

- Longreads

- High School Football