Over the past year, schools and libraries around the country have been banning a whole lot of books. And while this is a nationwide phenomenon, no state’s schools have embraced the practice of declaring certain stories and perspectives forbidden to their young people the way that Texas’s have. According to a list compiled by the literature and human rights nonprofit PEN America, between July 1 of last year and June 30, Texas has seen 801 bannings. That’s a huge number! Compare that with, say, Alaska or South Carolina, which have banned one book each. (In both instances, it’s Maia Kobabe’s award-winning comic book memoir Gender Queer, which has also been banned in nine districts in Texas.)

That figure—801 banned books—refers not to individual titles but rather to the number of times any school district has issued a ban. Some titles, such as Gender Queer, appear multiple times, having been banned from Canutillo (fifteen miles northwest of downtown El Paso) to Clear Creek, 785 miles to its east. Others, such as Brent Sherrard’s Final Takedown—a slim, out-of-print volume from a small Canadian publisher about a kid who faces time in juvenile detention—appear but once (in San Antonio’s North East Independent School District, the most avid banner of books in the state). Some are banned in school libraries, others in classrooms. Some have been removed pending an investigation that the school district may or may not have the time and resources to conduct in a timely manner. Most have been banned by administrators, while others are the result of a formal challenge from a parent or other community member. In any event, the guiding principle remains the same: to ensure that students are not exposed to ideas that their elders do not want them to consider, by making it increasingly difficult to access the volumes in which those ideas are contained. (Teenagers are, of course, famously respectful of such rules, and rarely seek out such materials on their own.)

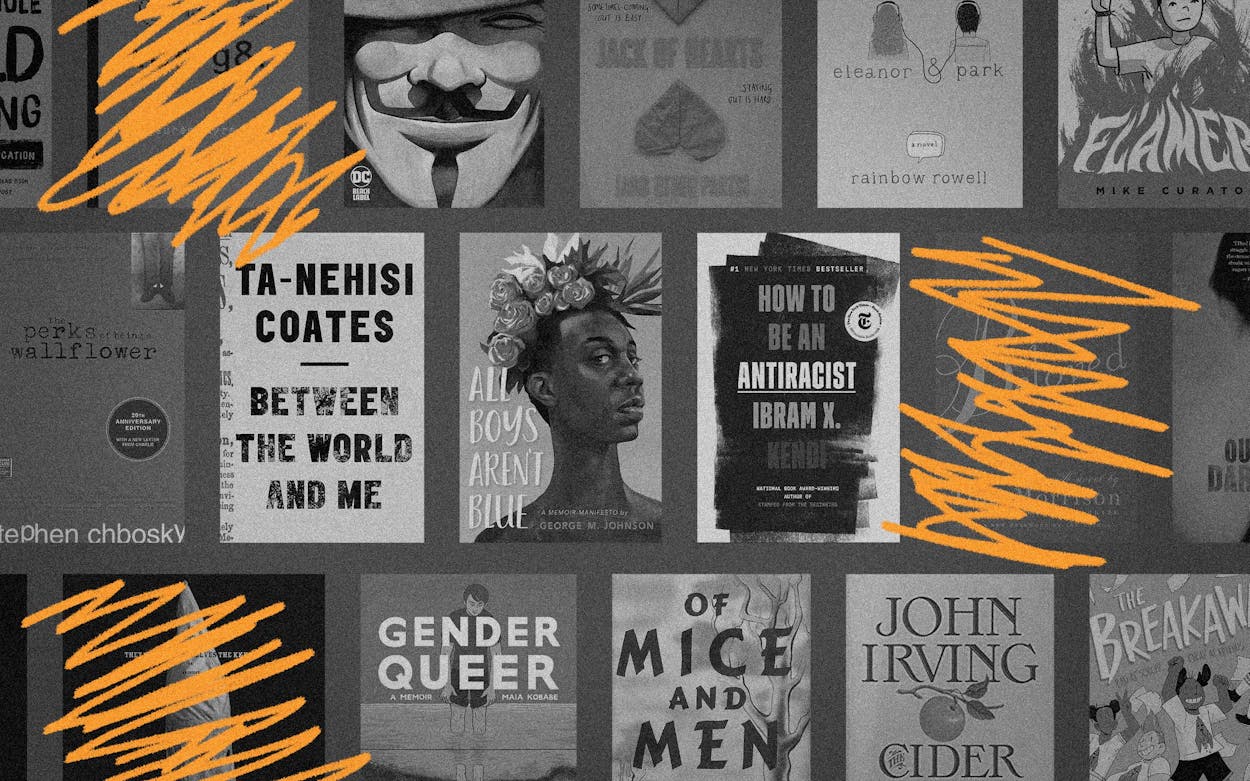

As the full list from PEN America indicates, book banning has become a popular cause among some in our polarized electorate—but this wasn’t always the case. Back in the halcyon days of, er, March 2021, some of Texas’s political leaders fervently opposed the idea of book bans, when the topic was the decision of Dr. Seuss Enterprises, publisher of the work of Theodore Geisel under his famous pen name, to no longer publish new copies of a handful of the author’s titles that included racist stereotypes. (Ted Cruz sold signed copies of Green Eggs and Ham in protest!) That may as well have been a lifetime ago, however, as the length and breadth of the list indicates. Texas has banned books about boys and books about girls, and books where the gender is more of a swirl. It’s banned books about sex and books about race, and books about those whose white hoods hide their face. It’s banned classics, and new books, and books in-between; it’s banned best-sellers, award winners, and books rarely seen. It’s banned books about what the Nazis did to the Jews, and beloved old books by the great Judy Blume. It’s banned comics, and prose books, and books full of poems; it’s banned slim volumes, and it’s banned hefty tomes. Texas has banned a huge number of books, indeed! And here’s a quick guide to the ones schools don’t want kids to read.

A PEN America notes, these are just the incidents that have been reported to the group—the reality of book bans likely extends further throughout the state. But here are some trends.

Books about gender identity and homosexuality

Kobabe’s Gender Queer, which explores the author’s journey to the realization that their identity is beyond the gender binary, is one of just a handful of books to appear nine times on the list. It’s hardly the only book about gender identity and same-sex romance to find itself banned in a Texas school or library, however. George M. Johnson’s “memoir-manifesto” about his coming out, All Boys Aren’t Blue, appears seven times; Susan Kuklin’s 2014 nonfiction collection of interviews, Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out, appears five times, as does Mike Curato’s comic book memoir Flamer. Even titles that seem downright clinical in their examination of the history of gay folks in America make the list—Jaime A. Seba’s Gay Issues and Politics: Marriage, the Military, & Work Place Discrimination, a 64-page explanation of its eponymous topic, has been banned twice. Four books by different authors with the title Gender Identity have all been banned in at least one district. It’s not just weighty titles getting banned, either—L.C. Rosen’s queer rom-com Jack of Hearts (And Other Parts) has been banned in eight districts, while The Breakaways, Cathy G. Johnson’s lightweight graphic novel about a kids’ soccer team, is banned in six because it includes a transgender boy among the players.

Books that are about straight people but have some sexual content

As the controversy around The Breakaways indicates, book-banners seem to contend that any depiction of gay or transgender characters—or nonfiction explorations of those identities—is inherently inappropriate for kids. When it comes to straight, cisgender folks, though, things have to get a bit more specific. Books such as Ashley Hope Pérez’s Out of Darkness, Jesse Andrews’s Me and Earl and the Dying Girl, and Lauren Myracle’s l8r, g8r all appear on the list (nine, seven, and four times, respectively) for touching on sexual themes, featuring teens who talk about sex, or depicting sexual abuse. For nonfiction, books that discuss sex or its consequences openly tend to make the list—titles include Margaret O. Hyde’s Safe Sex 101: An Overview for Teens, Donna Lange’s Taking Responsibility: A Teen’s Guide to Contraception and Pregnancy, and Chloe Shantz-Hilke’s My Girlfriend’s Pregnant! A Teen’s Guide to Becoming a Dad (which seems like a useful book for kids in that situation!). And abortion, in any context, can get a book banned: Melody Rose’s Abortion: A Documentary and Reference Guide and Johannah Haney’s The Abortion Debate: Understanding the Issues, relatively straightforward histories, are on the list, as are books on the history of Roe v. Wade. Even dad-friendly political thrillers can land on the list if abortion comes up—bestselling author and occasional Fox News contributor Richard North Patterson’s Protect and Defend received an administrator’s challenge as well.

Books about race

The fervor around “critical race theory,” which describes an academic framework not taught in public schools, means that it doesn’t matter how well regarded a book about race is—such titles are all over the list of banned books. Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates’s National Book Award–winning book-length letter to his young son about growing up Black, is on the list, as is his We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy, which features essays on race in America. One needn’t be a National Book Award winner to get on the list for writing about race, either—Duncan Tonatiuh’s history book for young readers, Separate Is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation, makes the list, as does Mychal Denzel Smith’s memoir Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching: A Young Black Man’s Education. Ibram X. Kendi’s books How to Be an Antiracist and Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America are both banned in multiple districts. Fiction bannings include some of the most acclaimed books in American literature: Toni Morrison’s Beloved and The Bluest Eye, Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, and white author William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner have all been removed from libraries. Poetry isn’t exempt, either—And Still I Rise, the third collection of poems by the great Maya Angelou, is on the list, as well.

Books about political violence, historical or speculative

If you’re a student who wants to learn about the history of the Ku Klux Klan, you may need to look outside of your school library to find the most acclaimed book on the subject for young adults: Susan Campbell Bartoletti’s They Called Themselves the KKK: The Birth of an American Terrorist Group isn’t on the shelves in three districts. Understanding how those roots affect the U.S. today might be a challenge too—Vegas Tenold’s Everything You Love Will Burn: Inside the Rebirth of White Nationalism in America, which traces the history of racist violence from the early days of the Ku Klux Klan to the events in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, is also on the list in two districts. Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize–winning history of the Holocaust, the comic book Maus, appears on the list, as does Ari Folman’s graphic adaptation of Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl. Even in fiction, books that explore fascist violence are verboten—the DC Comics graphic novel V for Vendetta, by legendary comic book creator Alan Moore, is banned in three districts for some reason. (The film adaptation, which similarly deals with anti-fascist themes, is also banned in China and Russia.)

Books where the vibes are wrong

For decades, Judy Blume’s Then Again, Maybe I Won’t, a puberty story from a boy’s perspective originally published in the seventies, has been a classic of the coming-of-age genre. The book hasn’t changed over the past fifty years, but frank storytelling about the issues high school students face frequently makes a book a target in Texas. Books about teen misfits such as Rainbow Rowell’s Eleanor & Park or Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower both appear. Perennial banned-book list titles such as Of Mice and Men make an appearance, as does John Irving’s The Cider House Rules. The DC Comics graphic novel Y: The Last Man also makes the list, maybe because it’s a science fiction story about everyone with a Y chromosome dying, and that’d be a bummer? Hard to say for sure, but in addition to banning books because they acknowledge that teens think about sex, or out of a desire to disappear queer folks and discussions of race from the conversation, some stuff makes the list just because of, like, vibes.

- More About:

- Books