This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

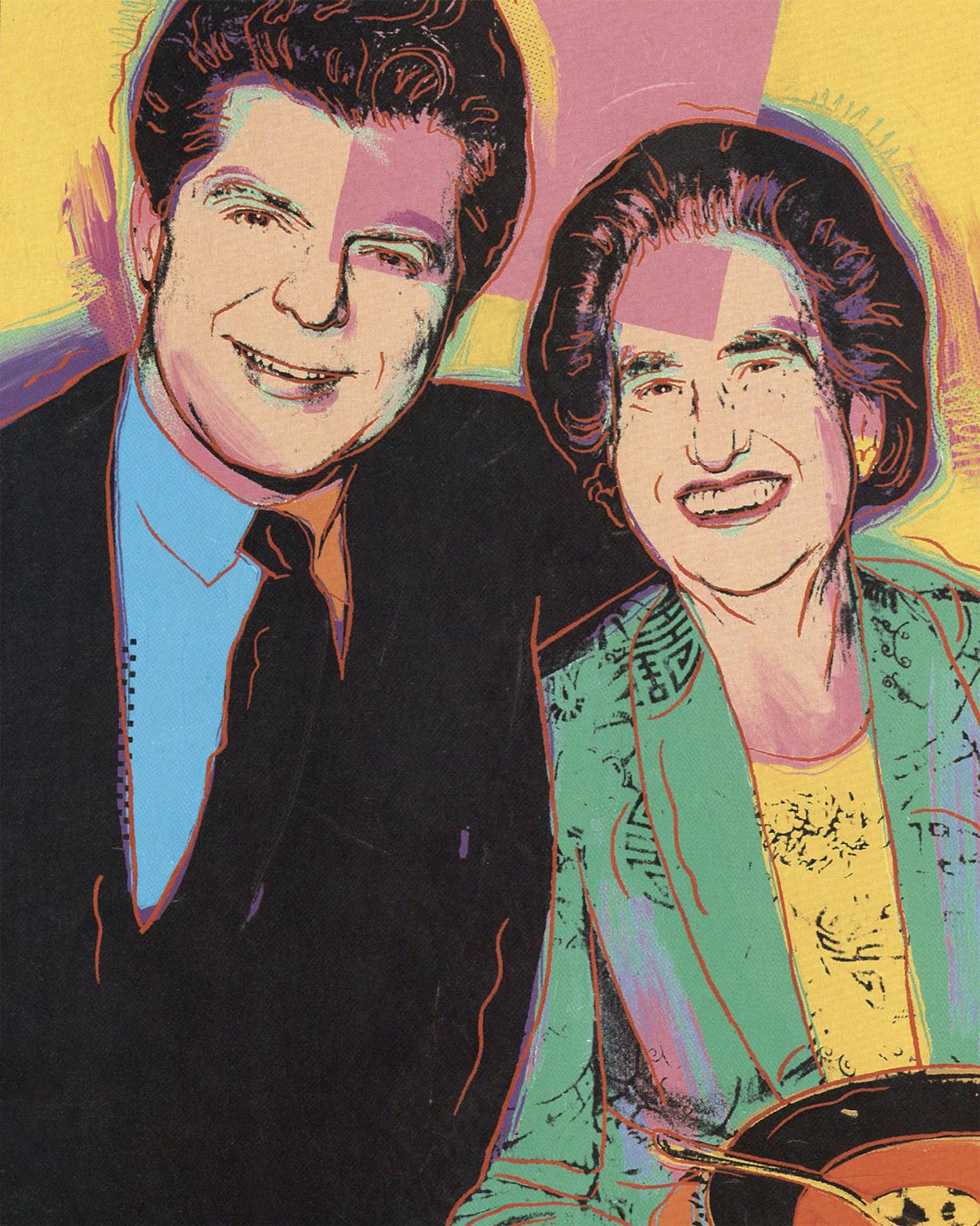

Come on in,” Van Cliburn said, leading the way down a short corridor to the breakfast room in his house in Fort Worth. It was four o’clock in the afternoon, a week before last Christmas, and Van Cliburn, wearing slippers and a dark blue bathrobe, had just gotten up for the day. At 52, the pianist looked far too young to have possibly won the first International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1958. His face had filled out, but otherwise it appeared to be untouched by the almost three decades that had passed since he burst upon the scene as that small-town Texas boy who became a hero of the cold war, embraced by Premier Nikita Khrushchev in Moscow and President Dwight Eisenhower at home.

Today Van Cliburn had an appointment, “I’ve just broken a tooth and have to get to the dentist before he closes,” he explained as we walked into the breakfast room. “But come on in, and you can talk to Mother while I change.”

Mrs. Cliburn was having lunch at the head of a long oval table, which is the nerve center of the old Kimbell mansion. The Cliburns bought the house in 1986, when they closed up their New York apartment. The mansion, previously owned by museum founder Kay Kimbell, is one of the largest and most famous houses in Fort Worth’s most exclusive neighborhood, old Westover. Mrs. Cliburn was wearing a blue quilted bathrobe and a bouffant pink nightcap that came down on her head like an overly large beret. At ninety, slight and frail, she seemed almost a waif at the head of the table. A friend of the Cliburns’, Tom Zaremba, came in from the kitchen, carrying a cup of coffee, wearing a white terry-cloth bathrobe and slippers. A compactly built man in his late thirties with chiseled features, a square jaw, and blond hair, he had a pleasant voice and that reassuring air of someone at complete ease. A housekeeper and a handyman were also coming in and out of the room, adding to the general stir precipitated by Van Cliburn’s imminent departure. Mrs. Cliburn patted the place at the table next to hers, indicating I should sit. “You can go to the dentist with Van, but sit down here and talk to me while he changes.”

On the long oval table there were several red and white poinsettias, assorted stacks of mail, a phone, and a gift basket of nuts decorated with a toy-soldier nutcracker. I had been there a week or two earlier at the same hour, and I noticed that she was having the same lunch—roast chicken, carrots, and green beans. “You must like chicken,” I said.

She opened her eyes wide and leaned toward me as if she were going to tell a joke. “That’s what they used to say at the Plaza Hotel—‘Would you be having chicken again for a change, Mrs. Cliburn?’ ”

“You eat it a lot?”

She looked at her plate and nodded. “I eat it every meal.” Then she closed her eyes and shook her head as if to savor a memory. “I used to love New York. We went everywhere, and we weren’t scared of a thing. Did I tell you that I studied with Arthur Friedheim in New York? I studied with Arthur Friedheim, and he studied with Franz Liszt. When Van was little and I was teaching him Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody, I would tell Van he was getting it thirdhand—from Liszt to Friedheim to me—and that wasn’t bad.

“I was Van’s only teacher until he went to the Juilliard in New York. No one had ever heard of him that first time he went to Moscow, even though he had won contests here. Friends said we were missing out on a fortune in publicity, but I told them that was all right, to let them think he was just a little boy from Texas. As Papa always said, ‘Brag is a good dog, but Holdfast is better.’ We could have told them what Van had done, but it turned out all right the way it was, don’t you think?”

Indeed, it couldn’t have turned out much better. Now, at a time when the name Van Cliburn has become one of those resonant echoes of the past, when he is better known in the world of classical music for his mysterious disappearance from the stage than for his playing, it is difficult to recall what a truly phenomenal success Cliburn had. Never before, and probably never again, has any classical musician become so famous so quickly. When he went to Russia at the age of 23—a six-foot-four-inch 170-pound gangling young man with two dress shirts, a plastic wing collar, and a gray Shetland sweater that showed under his jacket when he took his bows—his career as a concert pianist had already stalled. He had won most of the major American prizes—including the Chopin and the Leventritt—and had performed with most of the major U.S. orchestras, but by 1958 his invitations to perform had fallen off, and he was in debt and back in Kilgore running the house for his ailing parents. Going to Russia was a desperate attempt to revive a career, and what happened surpassed all reasonable expectations.

Van Cliburn struck some chord deep in the Russian psyche, rekindling a memory of what a great pianist was supposed to be. Musicians and critics compared Cliburn’s playing, his appearance, and his triumphant tour of Russia to those of Franz Liszt a century earlier. The Russian public embraced Van Cliburn; total strangers would stop him on the street to hug and kiss him. Women wept and fainted at his concerts.

When Van Cliburn returned to the U.S.—it was six months after the Russians launched Sputnik—Americans treated him like David coming home from slaying Goliath. New York City gave him the only ticker-tape parade ever given a classical musician, and Time magazine put him on a cover bannered “The Texan Who Conquered Russia.” In Philadelphia shrieking fans ripped the door handles off his limousine. Cliburn’s invitations to perform increased dramatically, as did his fees, and he signed a recording contract with RCA Victor that, according to Time, was the “fattest ever offered a young artist, with built-in guarantees for long-term security.” It was rumored that his income that first year went up to $150,000, and soon he was earning half a million dollars a year.

It was incredible celebrity, and the best part was that it was well deserved. Van Cliburn behaved like a born statesman. He always said the right thing. He always made the right gesture. But most important, there was the music, that clear font from which it all sprang. Twenty-two years later, the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians wrote that Cliburn “was admired for the completeness of his technical command and for his massive, unpercussive tone. Even more remarkable was his musical taste, which, although it could produce rather distant performances of Mozart and Beethoven, gave his playing of the Romantic repertory an extraordinary character of grandeur combined with both chastity and warmth.”

All of this, of course, leads to the question, Why did Van Cliburn simply stop playing in 1978 and what is he doing today, living in the old Kimbell mansion in Fort Worth?

Several moments later, Van reappeared in a navy-blue three-piece suit, a white shirt, a dark blue tie, and a cashmere topcoat, the tails flapping behind him. He looked rather formal and dramatic, an impression enhanced by the speed at which he walked, his chest out as if he were cutting through waves. While he talked to the handyman about a mobile telephone he wanted to take to the dentist so he could stay in touch, Mrs. Cliburn watched Tom Zaremba walk into the vaultlike refrigerator in the kitchen. Mrs. Cliburn had met Tom more than two decades ago at a small Midwestern college when he was assigned to show her the campus in preparation for one of Van’s tours. The young man was so nice that Mrs. Cliburn introduced him to her son, and since, Tom has become a close friend of the family. Mrs. Cliburn watched until he emerged from the refrigerator, then said, “I always wonder what would happen if the door should close while you’re in there.”

“Why, nothing, Rildia Bee. There’s a latch inside. I would just push it and walk right out,” said Tom.

“That’s good. I always worry when you’re in there.” She returned her attention to her chicken until her son came over to kiss her. “Good-bye, Little Precious,” he said, then we went through the kitchen and the side foyer to an enclosed courtyard for the family cars. A new white Lincoln Continental was sitting next to two dark blue Lincolns, which, paint faded, had an abandoned look. There was also a new station wagon parked at the end of the line. “You broke a tooth?” I asked as we got into the white Lincoln.

“No, I pulled out a filling while I was flossing this afternoon,” Van explained as he started the car. “It’s funny how those things happen. Mother needed to go to the dentist, and our regular dentist couldn’t take her, so we had to call around and find someone. I just took her yesterday, and now I’m going back.”

As he drove, he talked about Texas. Both of his great-grandfathers on his mother’s side were early settlers of McLennan County. One of his great-grandfathers was a co-founder of Baylor University, and his mother’s father was a lawyer, a newspaper publisher, and a member of the Legislature. Mrs. Cliburn was born Rildia Bee O’Bryan in McGregor, a town not far from Waco. As a child, Rildia Bee took lessons from Prebble Drake, who had studied at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music and who at age 97 heard Van play at the Los Angeles Hollywood Bowl. Rildia Bee herself attended the same conservatory, then went on to New York, where she studied at an institution that eventually became part of the Juilliard School. She was on the verge of going on tour as a concert pianist when her parents objected, insisting that she return to Texas. She married Harvey Lavan Cliburn, an executive with Magnolia Petroleum. They were living in Shreveport, Louisiana, when their only child, Harvey Lavan Junior, whom they called Van, was born. Then, when Van was six, they moved to Kilgore, which is where they stayed until he graduated from high school. “I may have been born in Louisiana, but I’ll be a Texan till I die,” he said as we pulled up in front of the dentist’s office.

The dentist and his staff were standing at alert. I waited in the lobby with the mobile telephone and Van’s overcoat, until he returned, a new filling in place. “You know, the thing about Texas,” he said back in the car, “is that it’s large enough and has enough resources so that it really is its own culture. I knew an opera singer—I won’t mention her name—who, when someone said something about the state she was from, someplace in the Midwest, she said, ‘Let’s just forget about that.’ Now, I have never known anyone from Texas, no matter how far they go or what they do, who isn’t proud of being from Texas.”

We were driving down a side street in a part of Fort Worth that looked almost deserted; there were low commercial buildings around us, and in the distance we could see the city’s skyline. “Don’t tell anyone, but I think I’m lost,” Van said. He slowed the car until we came to the next street sign, then, having found his bearings, turned the car around. When we came to a large florist’s shop, he pulled over next to the curb, blocking the drive to the parking lot.

Inside, the shop had a pleasant, old-fashioned atmosphere. One of the owners greeted Cliburn and took him behind the counter, where she had a large cardboard box of tiny wooden grand pianos that she wanted him to see. “I thought you might like these,” she said, putting a red one on the counter before him.

He nudged the piano with a very long, white index finger and winced. “You know, I’ve never been wild about pianos.”

“You haven’t?” I asked.

“Not really. A lot of people seem to revere them, as if they were an art form, but I’ve always thought of a piano as a necessity, the instrument through which I express myself.”

“Was there an instrument you would have preferred?”

“Oh, my, yes, the human voice. That’s the most beautiful instrument of them all. I still wish that I were an opera singer. I sang when I was little—soprano—but when my voice changed, that was the end of that.” He nudged the piano again. “Why don’t you let me have a dozen of these? I can give them away.”

We went into the greenhouse, where he picked out a couple of poinsettias. While he waited for the bill, he said, “You know, I’ve always loved flowers. When I had my first little apartment in New York, there was a florist’s shop on the ground floor of my building, and a lot of times I would spend my lunch money on flowers. But the odd thing about me is that I enjoy flowers as much when they get old and dried out as when they were fresh. I don’t know—I just look at those flowers, and in my mind, I still see the beauty they once had. I never threw any of them away.”

It was starting to get dark as we drove home. When we came to Camp Bowie Boulevard, we stopped at another florist’s, obviously new and much more fashionable. The shop smelled like narcissus and evergreens. On the clay-tile floor, there were two large rustic baskets filled with poinsettias. “Oh, look,” he said, pushing back the poinsettias so that the baskets came into view. “They’re shaped like reindeer.

“And look at this.” He pointed out a toy hot-air balloon carrying a tiny Santa in its basket, which appeared to have floated straight out of the nineteenth century. “Look at the craftsmanship. I have to have this,” he said when the owner of the shop came up. “And I’ll take these reindeer baskets.” “Which one?” asked the owner.

“Both of them.”

The owner, a man in corduroy trousers and a plaid shirt, remained remarkably impassive as Van proceeded to clean out his showroom. At a certain point we began to wonder if everything would fit in the car. Van said he was sure that it would, so we started carrying his purchases out. He paused to write a check, then handed it to the owner, saying in a low voice so as not to be overheard. “I just made it for an even thousand. I hope that’s all right. If that’s not enough, send me the bill. And if it’s too much, just apply the extra to my account.”

The owner allowed that that would be all right, and we made a last trip down to the white Lincoln, which, with its back seat and open trunk filled with red poinsettias, looked like a floral display. The trunk wouldn’t close, but the problem was solved almost immediately by the arrival of the florist’s delivery van.

“Was Christmas always a big event in your family?” I asked, once we were back in the car and on our way.

“Oh, I don’t know,” he said, pausing to think. “I guess about average. But, you know, it was strange. I was born on Thursday, July twelfth, and my grandmother, Mother’s mother, was living with us then, and she decided it was going to be a special Christmas with a baby boy in the house. She went out and bought all red ornaments and all red lights. Everything was going to be red that year. She was going to make it the best Christmas ever.”

“Your mother or your grandmother?”

“My grandmother. She was the one who had money. But then, on December thirteenth, a Thursday and her birthday, five months after I was born, Grandmother died, and Mother was so sad. They changed all the lights and all the ornaments, and we had a blue Christmas. After that, Christmas always reminded Mother of her mother’s death, so it was always sad.”

“Is it still?”

“No. It’s been such a long time.”

The lights were on in the house at the end of the driveway. When we came in, Van carrying the Santa and I bringing pots of poinsettias, Mrs. Cliburn, still seated at the end of the table in her bathrobe, exclaimed in a delighted voice, “Oh, Sonny, what have you done?”

Tom Zaremba, also in his bathrobe, was sitting at the middle of the table, going over papers with a pudgy accountant whose hair was slicked straight across his head in an attempt to mask a receding hairline.

“Look at this,” Van said, holding up the toy hot-air balloon and Santa. Tom and the accountant stood up to admire it, then Van showed it to his mother. “Let’s hang it,” he said, leading the way out of the kitchen.

On the right, there was an intimate-looking family dining room, but we went through a larger formal dining room into a square entrance hall that on one side opened into a library, where there was a nine-foot-long black concert grand piano, and on the other side, an immense living room with another concert grand and several distinct groupings of chairs and sofas, bounded by pots of poinsettias. At the end of the room, beyond the fireplace, was a solarium with yet another grand piano. The furniture was English antiques, and on the walls there were several large nineteenth-century English oil paintings. A wreath, easily six feet across, was hanging from the bay window at the front of the house; six or seven Christmas trees of various sizes and shapes loitered about the living room; and swags of evergreen decorated the mirrors, paintings, and cornices in the entrance.

Van and Tom took the balloon into the living room, looking for a place to hang it, but deciding it needed a position of greater prominence, they came back to the entrance hall, where Mrs. Cliburn, deterred by a step down into the living room, had taken a chair. They were just trying the balloon in the doorway to the music room when the doorbell rang and the delivery boy from the florist brought in the baskets, which were placed on either side of the entrance hall. Van tipped the boy, then the search for the perfect place continued, until the doorbell rang again and four high school students from Fort Worth Country Day came in to collect canned goods for the poor. Van asked if money would do, then went to get his wallet.

I took the settee next to Mrs. Cliburn, and the accountant sat down across from us, while Tom continued to try the balloon in various places. I could tell by the growing size of the students’ eyes that we must have looked like an odd group. When Van returned with a $20 bill and they left calling, “Merry Christmas,” I had the strange feeling that the world was a benign place. I could see that the accountant was feeling the same way. He had an entranced look on his face and seemed perfectly happy to sit there until the balloon was finally hung and Tom called him and Van back into the breakfast room to go over the papers.

“This is an extraordinary house,” I said to Mrs. Cliburn, noticing how good the golden oak cornices and moldings looked against the interior walls of smoothly cut white limestone.

“What’s that?” said Mrs. Cliburn who had an agreeable habit of drifting off, then, when spoken to, completely focusing on the person, her eyes wide, a smile on her mouth.

“The house. It’s a wonderful house.”

“Oh, isn’t it? The first time Van brought me to see it, I told him, ‘This is the house for me, if’”—she held up a finger—“ ‘we can afford it.’ If it was too much money, I didn’t want him to buy it. We had looked at so many houses—ranch-style houses on one level so that I could get around. We couldn’t have considered this house except it had an elevator, but since it did, it was just perfect for us.” She narrowed her eyes and looked toward the living room doorway. “I do wish that step wasn’t there.”

“I suppose there’s still a lot of house to roam in.”

“Oh, my, yes. I have a basement I’ve never seen and an attic. And there are four apartments over the garage—or I guess they’re rooms. I’ve never seen them either. But I’ve been so fortunate. Van has always been so good to me, and I give the credit for that to his father. When Van was just a little boy and his father was going on a trip, he would tell Van, ‘Sonny Boy, now, you take care of your mother.’ ‘Yes, Daddy!’ ” she mimicked a high-pitched voice and laughed to herself. “I was so lucky, and I’ve always said that the best thing a child can have is two parents who really love each other. I know that’s how my mama and papa were. My older sister used to say, ‘Mama is so proud to be Mrs. William Carey O’Bryan.’

“But Van was always such a good little boy. I never had any trouble with him. And right from the beginning, he had such a love for music. He would sit and listen while I practiced or gave my lessons. He didn’t want anything more than to get up on that bench with me. I’ll never forget when he was three, he was listening to me give Sammy Talbot his lesson. Later, I was in the kitchen when I thought I heard Sammy playing. I went in to tell Sammy that he must go home, that his mother would be worried. And there sat Van, playing Sammy’s piece. He had learned it by ear. That’s when I knew that Van had talent, and it was then that I began teaching him. He was such a teachable child.”

When Van was four years old, he made his recital debut at Dodd College in Shreveport. Then the Cliburns moved to Kilgore, and later, when asked where he grew up, Van would quip, “Highway Eighty,” indicating how much time they had spent driving in to Dallas. His mother would take him to concerts, and after he became famous, solo artists would recall Mrs. Cliburn’s coming backstage with Van in tow. But unlike stage mothers, she talked about music rather than her son’s accomplishments, apparently assuming that he would eventually be recognized.

Van’s father had hoped that Van might become a medical missionary, but when it became clear that his future was music, Mr. Cliburn had a studio built on the back of the garage of their modest white frame house. Van practiced for an hour before school, again in the afternoon, and if it wasn’t one of the four evenings a week when the family participated in activities at the Baptist church, again after dinner.

The family completely revolved around Van; every sacrifice was made for his talent. He was a good, if not brilliant, student who was ambitious enough to take summer courses so that he could graduate from high school when he was sixteen. He has recanted an early quote that childhood outside his family was a “living hell,” but it is difficult to imagine that he had many peers in Kilgore. Not only did his love for music set him apart—he was excused from PE classes lest he injure his hands—but by the time he was fourteen, he was a tall, awkward youth.

Early fame and fortune, however, did not bring an end to the family’s sacrifices. In 1962 impresario Sol Hurok hired Mrs. Cliburn to be her son’s road manager. “Because I’m his mother and tour manager, I can’t quit and he can’t fire me,” she would joke, but the job meant spending a good part of the year on tour or at the Salisbury Hotel in New York City, where Van kept an apartment, which, over the years, increased a room at a time until he had eight on one floor and six on another. When Van’s father died in 1974, his obituary said that he had told an interviewer that it wasn’t easy to have his wife and son away so much in pursuit of a musical career.

After talking for a while, Mrs. Cliburn turned her head toward the breakfast room once or twice and said in a vexed tone, “Where is Van?” which is, of course, the question so many people ask.

It is not unusual for a concert pianist to have prolonged and inexplicable gaps in his career. Vladimir Horowitz was absent from the stage for twelve years. Such an absence is mystifying because there is something fundamentally mysterious about music and the ability to make it. One person can play a passage, and it is resonant with meaning; another person can touch the same keys in exactly the same order, and what comes out is empty.

When Van Cliburn won the Tchaikovsky Competition, friends worried that so much fame at such an early age would rob him of the opportunity to expand his repertoire and develop as a musician. He would be trapped between fans who demanded that he play the same signature pieces again and again and critics who wanted him to explore. Indeed, looking through a Van Cliburn press file, one gets the sense that after that initial and sure ascent in which the goal was so clearly marked, his career and life appeared to drift a bit upon what must have seemed a featureless plateau of celebrity.

In 1967 the Dallas Morning News’ Washington bureau reported that Van Cliburn had refused to leave his hosts’ kitchen at a black-tie dinner party in his honor following a concert at Constitution Hall; the audience had demanded four encores, and Cliburn had been trapped in his dressing room by 150 devotees. By 1970 the music critic for the Houston Post was complaining that for the third time in a row Cliburn had walked on stage late for a Houston concert and that his playing had become “a bit ticky tacky.” In 1973 the Associated Press ran a story saying that a Van Cliburn “minicult” was forming in the Philippines. Imelda Marcos had invited the pianist to Manila, and a month in advance, government-controlled radio stations had broadcast excerpts from his repertoire, movie theaters had played his records at intermissions, and fashion designers had turned out “the Cliburn line—an array of gowns to make anyone beam with pride . . . while imbibing Cliburn’s music.” During a gala at the Malacanang Palace, Mrs. Marcos, a soprano, had joined in singing Cliburn a love song from the central Philippines, and the evening had ended with the company singing “Deep in the Heart of Texas.”

By 1978, when Cliburn stopped touring, critics were saying that his music had lost its early freshness. They said that he had always been an intuitive musician and that he lacked the intellectual curiosity that would keep his music alive and growing. Cliburn did not acknowledge the criticism nor did he announce his retirement. He simply stopped accepting engagements, saying it was time for an intermission in his career. After his nine-year absence, people are beginning to speculate that Van Cliburn might never come back.

“I wonder where Van is,” Mrs. Cliburn said again. “Do you want me to call him?”

Before she could, Van came in and sat down on the settee, saying that he had had to take care of year-end business. Early in his career, having received sound financial advice, he started investing his phenomenal performance fees and recording royalties in real estate and now has holdings in the Southwest. Without being asked, he volunteered an answer to the larger question of where he has been.

“I always said that I was going to work at the beginning of my life and at the end of it, but that I was going to take the middle off,” he said. “And I must say I’m enjoying it. When I wake up, I feel like I did when I was eighteen. In fact, I feel better. I was four when I made my recital debut and twelve when I made my orchestral debut with the Houston Symphony, but I don’t feel like I missed having a childhood. When I look back, it seems like I had a wonderful childhood. Music was my life, and it still is. I practice, and I’ll start performing again soon. I’ve always thought of myself as a servant. I can do something most people can’t. When I play, I’m providing them a service. But right now, this is my intermission. Every good concert program has an intermission, and I’m waiting for the second half to begin.”

He was about to go on when we heard new voices in the kitchen; then Richard Rodzinski, the executive director of the Van Cliburn Foundation, and his wife, Beth, came in.

“Rildia Bee, aren’t you coming to dinner with us?” Beth asked when she saw Mrs. Cliburn in her bathrobe and pink nightcap.

“Go ahead, Little Precious, and get dressed,” said Van.

“You want me to go?”

“Of course we do, but go ahead and get ready.”

“Do you want me to come upstairs and help?” Beth asked.

“No. That’s all right, Little Darling. I can manage.”

Drinks were served. Richard and Van went into the kitchen to discuss a budget cut the Van Cliburn Foundation had suffered at a meeting of the local arts council, and Beth offered to give me a tour of the house. She took me up the front staircase to the second floor, where we wandered from one bedroom to the next, coming across several pianos along the way. “Those are their bedrooms,” she said, indicating a part of the hall that could be closed off with iron security gates. “I don’t guess we should go in there. But let’s go up to the third floor. I’ve never done that before.” As we climbed the stairs, Beth told me that when the Cliburns moved into the house, it was the largest move in history—their possessions filled four entire moving vans. “Well, at least one of the largest in the history of Allied Van Lines,” she qualified.

A door sealed off the third floor. Beyond, it was dark and cold and the floor uncarpeted. When we turned on the light, midway in the hall, there was what appeared to be a giant wedding cake, tier after frosted tier, wrapped in cellophane. We thought it was real until we touched it, then we could tell it was a cardboard cake. After speculating about what the cake could be for, we took the service staircase back down to the kitchen, where Van and Richard were sitting at the breakfast table and Tom was padding around in his slippers and robe. “Pardon us for snooping,” said Beth, “But what is that cake doing up there?”

“Oh, that,” Van said and laughed. “When we celebrated Mother’s ninetieth birthday, we ordered three cakes—one for the symphony, one for a party at Perry and Nancy Lee Bass’s, and one for here. We never cut the cake here. After a couple of days, the woman who baked it called to ask if we wanted her to take the remains away. I told her no, that I liked looking at it. Then she called back later and said, ‘Don’t eat that cake!’ She was worried that someone would take a slice and get sick. Knowing how sentimental I am, she offered to make a model of it, and, of course, I said yes. I can’t bear to throw anything away.”

“And how many pianos are there in this house?” I asked Tom, who was setting up a portable typewriter on the breakfast table.

He looked up at the ceiling and appeared to be counting. “Fifteen, I think, a couple are uprights. Van used to travel with a concert grand until one time while he was watching it be unloaded from a plane, it fell and shattered before his eyes.”

“That makes a better story, but I wasn’t there to see it,” Van said.

“I always thought you were.”

“Aren’t you coming to dinner with us, Tom?” Beth asked.

“No, I can’t,” Tom said, sitting down to the typewriter.

“Oh, come on and get dressed.”

“No, I have to type an exam.”

“Are you a teacher?” I asked.

“I’m an undertaker,” he said and smiled. “And I teach mortuary arts at Wayne State.”

“In Detroit? You commute?”

“It’s not that bad.”

Mrs. Cliburn had just come in dressed for the evening. She had put on a bright patch of red lipstick and bold, dark eyebrows. She was wearing a pink-and-black knit suit, a sable hat and coat, and high heels. She carried a brown aluminum cane. Everyone told her how wonderful she looked, then Beth asked if she would play the piano for us. “Please, Rildia Bee,” Richard said. “Play for us.”

“Go ahead and play,” said Van.

Mrs. Cliburn consented, and we all went into the library. She sat down at the concert grand, touched the keys several times, the notes jangling until she found her place, then she started to play and sing in a high, old-fashioned voice a turn-of-the-century English song with the chorus, “What good is water when you’re dry, dry, dry?” It was clear from her comic timing, the phrasing, and the style she brought to it, that she was a born performer. She had just finished when the chairman of the Van Cliburn Foundation, Susan Tilley, a tall, striking woman in a mink coat, arrived, and it was time to go.

The last customers were leaving the Carriage House, a small restaurant on Camp Bowie, when we arrived, but it was clear from the maître d’s greeting that he was happy to keep the kitchen open late for the Cliburns. Although Van Cliburn has become a figure of mystery to the international world of music, he is hardly a recluse in Fort Worth. The Cliburns attend evening services at the Broadway Baptist Church and are seen at most of the musical events and interesting parties in town. At parties Cliburn has an almost LBJ-like quality—a tall figure who reaches and touches people, bringing them together.

Van took everyone’s orders himself, going back and forth to the kitchen, making suggestions about what we should have. Susan Tilley said that she was studying for a final exam in Russian, that a trip to the last Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow had inspired her to learn the language.

The Van Cliburn Foundation was the topic of much of the conversation at dinner. Started in 1958 by Irl Allison, the founder and president of the National Guild of Piano Teachers, the foundation holds the Van Cliburn Competition every four years and sponsors a series of performances in the intervening years. Apart from being a member of the board of trustees, Cliburn has no official connection to the foundation, but he has attended all seven of the competitions and has been generous with his time, money, and advice. Richard said he calls Cliburn two or three times a week, that he counts on not only his artistic judgment and administrative wisdom but also his vast network of friends in the world of music. Cliburn was particularly pleased that William Schuman had agreed to write the commissioned work for the 1989 piano competition; Schuman, one of America’s leading composers, was the president of Juilliard when Cliburn studied there.

About halfway through the dinner—at close to midnight—I looked over at Mrs. Cliburn sitting at the end of the table opposite her son, her eyes closed, resting peacefully over her plate of chicken.

When we got back to the house, it was after one in the morning. The Rodzinskys had gone on their way, but Susan Tilley and I rejoined the Cliburns in their breakfast room, where Tom had just finished typing his exam. “Still here?” I said.

“And still in my bathrobe. I suppose you’ve never seen me in anything except a bathrobe.”

“No, the first time I was here, you were wearing a suit.”

“His undertakin’ suit,” said Van as he poured coffee.

Mrs. Cliburn sat at the head of the table and started opening a stack of mail. It was clear no one had any intention of going to bed. “Gee, you really stay up late around here,” I remarked.

“Concert pianists usually keep late hours,” Susan explained. “Their workdays don’t begin until eight in the evening.”

“And I don’t think Van ever got back on western time after spending so much time with his friends in the East,” Tom added, in an apparent allusion to Imelda and Ferdinand Marcos.

“Well,” I said, “I don’t see how you stay up so late—particularly Mrs. Cliburn.”

Van looked at his mother, who, still wearing her sable hat and coat, was going through the mail, paying no attention to us. “You know, two years ago, she was on a walker. We bought her a wheelchair, and we thought she would never get out of it. Then she had this whole new burst of energy,” Van said.

Tom opened his eyes wide and shook his head. “It’s weird.”

A week later, when I stopped by the Cliburns’ house late in the afternoon on the way to the airport, I felt apprehensive. I remembered my evening with them as such a special time; I liked to think of them as living in a world apart, where everyone was always happy and called each other Little Darling and Little Precious. I was afraid something might have changed, but when I arrived, Van was in his blue bathrobe, his hair messed up from sleeping. His mother was sitting at the end of the table in her blue bathrobe and pink nightcap, eating roast chicken. Tom was getting ready to catch a plane to Detroit. When I asked Mrs. Cliburn how she was, she said with real delight, “I’m still alive!” She leaned forward confidentially. “You know, people tell me that I’m ninety years old. Isn’t that just awful to live such a long time?”

“No, not if you’re enjoying it. And you seem to be.”

“Oh, yes! Have you seen my Christmas tree? Van, take him to the living room so he can see my Christmas tree.”

I followed Van into the living room, where there were so many pots of poinsettias that they looked like banks of ferns growing on a forest floor. The Christmas decorations, it appeared, had been multiplied by two; there were more wreaths and swags of evergreen, and at the end of the room in front of a window stood a tall fragrant spruce, decorated with lights and ornaments and scrolls of music.

As we looked at the tree, I wanted to ask Van when he would come back, but I figured he didn’t know. Genius, like music, is mysterious. It doesn’t follow rules. It exerts its own toll. It taps deep, sometimes hidden wells. Van Cliburn had always been known as an intuitive musician, one who could play his emotions. Standing there, I had no sense of him as a tortured artist casting about for new meaning. He seemed happy and confident that when the time came, his music would have plenty to say.

Van Cliburn’s Greatest Hits

Van Cliburn’s recordings are somewhat out of style, and about half of them are now out of print, although planned reissues on compact discs might change that. For an artist so popular during the time he was making records, he made relatively few—only thirty or so in his career. When listened to afresh, their quality seems consistently high. Concertgoers who heard Cliburn only in the years before his abdication of the stage, during which time he turned out some lax and untidy performances, will be surprised by the meticulously prepared and scrupulously played recordings. If they seldom turn up on critics’ lists of recommendations these days, one can partly blame fashion and partly blame Cliburn’s habit of recording the most basic repertoire (of the sixteen concertos Cliburn has recorded, fifteen could be called the fifteen most-popular piano concertos).

Here is a selection of Cliburn’s recordings that are most worth listening to:

Tchaikovsky Concerto No. 1 in B-flat Minor, Opus 23, with an unidentified orchestra conducted by Kiril Kondrashin (LSC-2252). Cliburn’s first recording to be released after his triumphant return from Moscow was for a long time the world’s best-selling classical recording, and with good reason. Besides its commemorative value (it features the leadership of the conductor who had accompanied the pianist in his Soviet victory), it has ample musical value. Cliburn already shows his characteristic combination of romantic fervor with classical discipline and restraint. Only a slight coarseness in the orchestral playing keeps this performance from eclipsing all other versions of the concerto.

Rachmaninoff: Concerto No. 3 in D Minor, Opus 30, with the Symphony of the Air conducted by Kiril Kondrashin (ARP1-4688). The second of Cliburn’s records for RCA is even more spontaneous and thrilling than the Tchaikovsky concerto, since it was recorded at a live performance just two days after his return from Russia. Like the Tchaikovsky, it has been reissued in RCA’s .5 series, which means that the new master disc was cut at half speed in an attempt to gain fidelity to the original tapes.

Beethoven: Sonata No. 26 in E-flat Major, Opus 81a (“Les Adieux,”), and Mozart: Sonata No. 10 in C Major, Opus 330 (LSC-2931, out of print). The Beethoven sonata is a fine performance—less fussy than Cliburn’s later recordings of Beethoven sonatas—but it is the Mozart that is the revelation. Cliburn here turns out some of the best Mozart playing on record, consistently alive and forward-moving without ever losing its elegance. A lot of the intellectual critics looked for Cliburn to take up the sword of high seriousness at this point in his career, but he didn’t oblige them. He never recorded Mozart again—or late Beethoven or any of the other super-highbrow works they wished he would tackle.

Chopin: Sonata No. 2 in B-flat Minor, Opus 35 (“Funeral March”), and Sonata No. 3 in B Minor, Opus 58 (LSC-3053, out of print). By this time—1968, about halfway through his recording career—Cliburn had evolved a more inflected, almost mannered, rhythmic style. Some of his later performances sound prissy next to his earliest ones, but this one has plenty of sweep and charisma to carry along all the fancy detail.

Prokofieff: Concerto No. 3 in C, Opus 26, and MacDowell, Concerto No. 2 in D Minor, Opus 23, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Walter Hendl (LSC-2507, out of print). Cliburn had an early success playing the little-heard concerto by Edward MacDowell, a nineteenth-century American composer, and this recording is a perfect opportunity for those who are dubious of the pianist to try out his playing. For once, they will be acquiring a performance of a work they are unlikely to encounter elsewhere, and they will be rewarded by the innocent lyricism of the piece as well as by the ardor of Cliburn’s performance.

Grieg: Concerto in A Minor, Opus 16, and Liszt: Concerto No. 1 in E-flat, with the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy (AGL1-5240). After the death of conductor Fritz Reiner—who accompanied Cliburn on some early recordings—RCA turned to Philadelphia and Ormandy for Cliburn’s more flamboyant romantic repertoire. Several of the performances have been reissued in the label’s less expensive Gold Seal series.

Prokofieff: Sonata No. 6 in A Major, Opus 82, and Barber: Sonata, Opus 26 (LSC-3229, out of print). Samuel Barber’s modern-sounding but lyrical sonata, which is about as far off the beaten track as Van Cliburn ever got on record, is one of his best performances. The blazing technique that has both these sonatas well in command is enough to convince any lover of the piano that Cliburn had all the goods.

My Favorite Brahms (LSC-3240). Brahms’ autumnal short piano pieces from his last years are some of the most beautiful music ever written, and Cliburn plays them with a special feeling for their ripeness and melancholy.

My Favorite Debussy (LSC-3283). Cliburn plays Debussy as nobody else has played him—with plenty of color and delicacy but full out, without the sometimes maddening overrestraint that the majority of musicians bring to this music. “Clair de lune” inebriates with the requisite moonlight, and “Reflets dans l’eau” presents some of the most liquid-sounding, gorgeously flowing pianism on records.

My Favorite Encores (AGL1-4910). This recital, despite its precious-sounding title, has a substantial repertoire on it, and the Debussy performances are attractive in their diversity and their assumption of the almost-vanished grand manner of the last century. —W. L. Taitte

The Day the Cold War Thawed

In these cynical times, it is difficult to recall the impact that Van Cliburn’s winning of the Tchaikovsky piano competition in Moscow had on us in the spring of 1958. Americans had been shocked by the launching of Sputnik in October 1957. Not only did the Russians have the bomb, but they also had the technology to drop it on us from space. As our government worked to counteract the military and propaganda advantage that the Soviets had gained, help came from a totally unexpected source. Van Cliburn appeared—“Horowitz, Liberace, and Presley all rolled into one,” as one of his friends told Time. We also got a glimpse of real-life Russians beyond the implacable commie stereotype. For a moment we thought the cold war might melt away under the warmth generated by the suddenly world-famous Texan.

At the competition it was obvious that Cliburn was the winner long before the competition’s president, composer Dmitry Shostakovich, presented the award. News reports left the impression that if adoring Moscow crowds were cheated of a win by the young man they called “Vanyushka,” there might well be another Russian revolution. But not even a bandaged index finger and a piano string that broke during Cliburn’s final concert could slow his momentum. The judges’ decision was unanimous.

I heard the news during English class at Munich American High School in West Germany, where my father was stationed with the U.S. Army. My teacher, a fellow Texan, made the announcement on a Monday afternoon. As everyone cheered, for the first time I felt the surge of an unfamiliar emotion: I was proud to be a Texan.

But many of us cheered for reasons other than chauvinism. We were as much amazed that Russians could play fair as that a pianist from Texas could win in Moscow. The cold war was no distant abstraction. A year and a half before, we had experienced the tense weeks following the Hungarian uprising, when American troops in Europe went on full alert. We were surprised and a little disappointed when World War III didn’t materialize.

A month after his win, Van Cliburn was back in New York following a triumphant tour of the Soviet Union, and he was astounded by the hero’s welcome he received. Variety called him “a musical Lindbergh.” He was that, all right. But I was impressed with what he told one reporter who asked him what effect his victory might have on the world situation. Resolutely unpolitical, Cliburn replied, “I think that political events come, and they pass. They have no staying power. But art always remains with us.” —Chester Rosson

- More About:

- Music

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fort Worth