On a chilly February evening outside Austin’s One-2-One Bar, an unassuming concert venue snuggled into a strip mall on South Lamar Boulevard, a lineup of promising young emcees wait to take the stage. East Side native Trenton Anthony (aka The Teeta) and Bastrop’s Devin “Deezie” Brown stand among them, as well as 33-year-old local rapper Kori “Mama” Duke. When Mama Duke reaches her turn, she delivers blow after lyrically complex blow from her self-produced LP, Ballsy, a commanding collection of tracks. With electrifying flow and head-banging stage presence, Duke captures the live-wire energy so many of us miss from live music—even if this particular performance, held before a sparse crowd of mask-clad cameramen and sound engineers, is primarily transmitted through SXSW audience members’ laptop screens.

It’s been a little over a year since the capital city’s live music industry ground to an abrupt halt, when an executive order from Austin mayor Steven Adler canceled the city’s annual South by Southwest festival. For many Austinites, the sudden shuttering of the massive event, just a week before it was set to begin, signaled that life wouldn’t be “normal” for a long time to come. Despite everything that’s happened over the past year, performing at SXSW—virtual or no—still represents something special for local denizens of the city’s hip-hop community: the chance to finally put Austin’s rap scene on the map. “People say ‘Austin rap had no breakout stars’ like it’s a bad thing,” says Duke. “I think it’s pretty awesome; it’s just making people hungrier. That skyline doesn’t belong to anybody—and that’s what I’m chasing.”

Austin is a city that’s often at odds with itself. It’s best known for hosting one of the nation’s largest music-industry gatherings—one increasingly dominated by rap in recent years, and that’s provided a launchpad for many musicians—but the city itself has yet to make a significant mark on the national hip-hop scene. That’s not to say a handful of Austin-bred artists haven’t tasted success over the past forty years; local emcee Papa Chuk’s signing to the major label Pendulum/EMI in the 1990s was a watershed moment. And more recently, the twenty-year-old East Side wunderkind Quin NFN has become a popular artist in the streaming era, amassing a combined 48 million Spotify streams off his top two tracks “Poles” and “Talkin’ My Shit.”

Still, Central Texas’s hip-hop scene is seldom mentioned in the same breath as those in the state’s more established creative epicenters, most notably Houston and Dallas. One issue stems from the fact that Austin doesn’t currently offer the essential infrastructure—namely, a critical mass of venues and labels—necessary to support the genre as a viable industry. According to the Texas Music Office, Houston currently holds more than twice as many hip-hop labels as Austin and its surrounding areas. “The whole problem is that the industry is yet to exist in Austin, as far as more than just the artistry,” says Cam Turney, a.k.a. Cam The TSTMKR, an Austin-based artist representative. “[Houston artists] are backed by somebody who believes in them and knows their culture . . . Here we don’t have very many lawyers or many investors that are going to create an actual ecosystem.”

Over the past year, Austin’s oft-overlooked hip-hop community has only become more ambitious, with emcees, rappers, and DJs emerging from their quarantine cocoons arguably at the top of their artistic games. And these creatives are hopeful that audiences will begin to see the city’s hip-hop scene in a new light—and the DJs who helm one of the city’s leading hip-hop radio shows, KUTX’s The Breaks, are keen on expediting that process. During the program’s first-ever virtual hip-hop SXSW showcase (South by South Breaks) last month, Austin’s reigning hip-hop artists delivered a memorable showing. Trap beats crashed, electric guitars wailed, and—in the livestream’s chat—virtual audience members typed furiously to express their admiration. “Where has ATX Hip Hop been all these years?” wrote one listener.

“Us as rappers, we don’t think of there being a scene dedicated to us in Austin,” says Duke, video chatting from her DIY North Austin home studio. For an artist who’s spent a career overcoming what she calls “three whammies” in a male-dominated industry—“I’m Black, female, and gay, and somehow still found a way,” she raps on “Found a Way,” a track from her latest album—it’s telling that one of the biggest obstacles Duke has faced in her career is the fact that she chose to move to Austin from her native Palacios, Texas, in 2009. While the move, in part, was motivated by the city’s “Live Music Capital of the World” designation, she was caught off guard when she initially arrived to Austin. “You hear these horror stories of talented local rappers never getting a fair shot—so many doors that wouldn’t open,” she says.

Historically, Austin’s hip-hop scene has lacked a cohesive identity. “For the longest time, what hurt Austin was people saying we didn’t have a sound,” adds Aaron “Fresh” Knight, a hip-hop blogger who co-hosts The Breaks with Confucius Jones, a local DJ. “Not like H-town in the mid-2000s with the real slowed-down, thick Southern drawl where you’d hear it and know, ‘That’s Houston.’” Adam Protextor, an Austin-based filmmaker, comedian, and rapper who performs under the stage name P-Tek, notes that Houston’s rap scene cemented its identity through the hits and acclaimed albums it produced throughout the nineties and early 2000s, including Geto Boys’ We Can’t Be Stopped, UGK’s Ridin’ Dirty, and Southern hip-hop godfather DJ Screw’s more than three hundred self-released tapes, colloquially known as Screw tapes. “Austin [by comparison] is not easy to characterize,” Protextor says. “One visual metaphor I use is ATX rap as a spiderweb with many connecting points: you have this incredible network of artists doing very different things, and they still vibe with each other. If you’re only focusing on one specific point, you need to zoom out to realize that web’s bigger than it seems.”

That spiderweb is quintessentially Austin: irreverent, endlessly entertaining, and weird as hell. And among longtime veterans in the city’s rap community and upstarts alike, there’s a growing belief that the latest generation of local rap acts, led primarily by artists including Mama Duke, J Soulja, Mike Melinoe, Riders Against the Storm, Vintage Jay, Magna Carda, Abhi the Nomad, Deezie Brown, The Teeta, Chucky Blk, among others, combined with a push to create infrastructure that can support creativity, might finally elevate the Austin rap scene beyond its city’s limits—even during a pandemic.

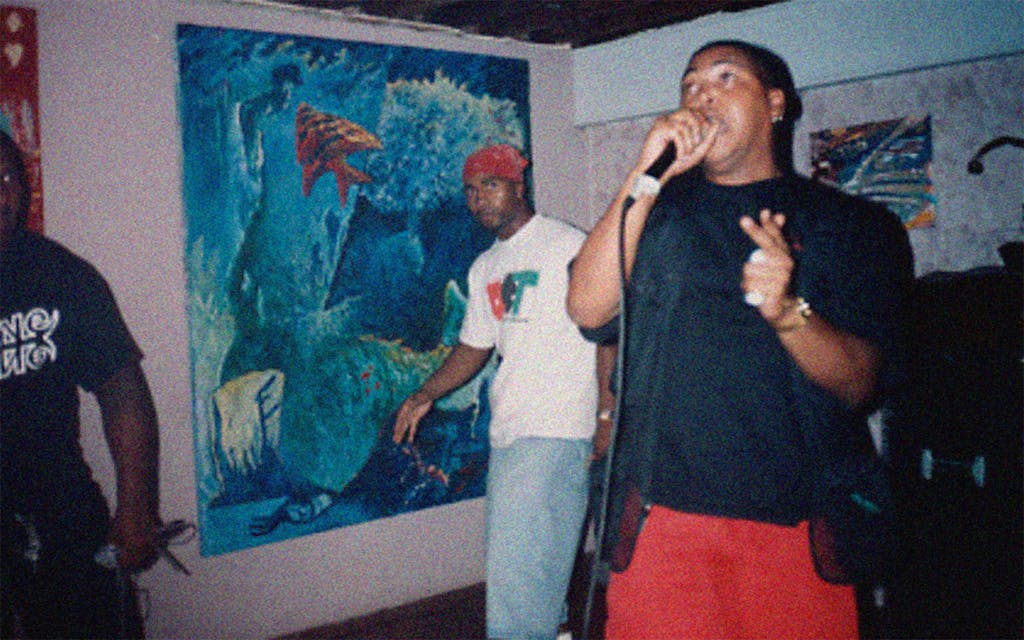

To tell the story of Austin rap, you have to go back to the late 1980s and early 1990s. Bavu Blakes, who became the second local rapper to play the Austin City Limits festival in 2008, says hip-hop shows in the Texas capital were born from communal gatherings. “You weren’t going to a show,” Blakes says. “You were going to a party.” Back then, spirited local collectives including the Disgruntled Seeds and the Coolie Girls performed mostly at venues on the city’s East Side, including Givens Park, Doris Miller Recreation Center, and Rosewood Neighborhood Park. Back then, artists would occasionally perform downtown at the then-sole Black-owned club on Sixth Street, Catfish Station. The city’s deep segregationist history is a significant part of why hip-hop was confined to East Austin neighborhoods and communities, which were populated by predominantly Black and Hispanic residents until the late 1990s.

However small, the influence of the city’s early rap scene—most significantly on the young artists of the day—can’t be overstated. “Hip-hop was one of the first things I saw in Austin that made me realize there was much more to this city than just university students coming to town,” says longtime Austin-based musician Adrian Quesada, one half of Grammy-nominated psych-soul outfit Black Pumas. Then an aspiring hip-hop producer from Laredo, Quesada remembers venturing east of his student dorm at the University of Texas to attend gatherings, including East Side rapper Nook Turner’s summer concert series, Jump On It, in the mid-to-late 1990s. Many of them were family-friendly events, as Quesada recalls. “I remember they had a thing where there was no cursing on stage,” Quesada says. “Because the hip-hop scene back then spoke, in a broad sense, to how Austin has this sense of community—even if we don’t have the industry that they do in Houston. That’s what I really love about this place.”

By the turn of the millennium, thanks to the hustle and lyrical talents of scene forebears such as DJ Casanova and MC Overlord, Austin hip-hop started expanding west of Interstate 35. Blakes’s popular Wednesday open-mic night, Hip-Hop Humpday—which he hosted alongside local artists Traygod and Tee-Double—provided a stepping stone for local talent at Sixth Street’s Mercury (now the Parish). Elsewhere, a younger generation of up-and-coming artists including Confucius Jones and Cam Turney were fixtures at East Side open mics held by Victory Grill, the now-shuttered Club 1808, and wherever else they could find an outlet for self-expression. “The places we [found] weren’t necessarily even dedicated to hip-hop,” Jones recalls. “But they were brave enough to say, ‘Yeah, we’ll let y’all come here and rap on our microphone for a bit.’ Sometimes that was just someone’s backyard.”

Austin’s growing status as a destination for national rap acts by the early 2000s mirrored the genre’s increasingly bigger presence at SXSW, which the festival’s pioneering hip-hop booking agents Kier Worthy, Andre Walker, Matt Sonzala, and Hip Hop Mecca worked for decades to achieve. But that same attention wasn’t always extended to local rap artists, says Cam Turney. “They were bringing hip-hop shows from already-big artists, but they weren’t letting any of us open for them or bring in shows of our own,” Turney says of that time. “It now felt like a competition instead of a community.”

Adam Protextor, who moved to Austin around 2008, says that he “never felt this connective tissue between the local shows I attended. ‘Why wasn’t this party artist meeting this conscious rap artist?’ I figured having one central space could go a long way to creating a sense of community.” In an attempt to foster a more cohesive community, Protextor teamed up with hip-hop radio DJ Leah “Miss” Manners and, in 2012, launched Austin Mic Exchange (AMX), a weekly gathering of up-and-coming emcees. Held at Spider House, a popular patio bar and artistic gathering space near UT Austin’s campus, the event eventually filled the void left by Hip-Hop Humpday, providing a launchpad for scene heavyweights including Chucky Blk and Ben Buck. AMX went on to inspire similar initiatives, including College of Hip Hop Knowledge and ATX Social Club.

But a strong community alone does not a nationally recognized scene make. Even before COVID-19, the handful of hip-hop-friendly performance spaces in Austin was hardly enough to support a thriving landscape. Additionally, such places rarely survived beyond their fifth anniversaries—downtown venues including Republic Live, Ironwood Hall, and Scratchouse, among others, have been casualties of what Jones says is an inhospitable musical climate. By contrast, hip-hop venues have fared marginally better in the likes of Houston and Dallas: According to the Texas Music Office’s industry directory, despite containing more independent venues on average per area code, Austin houses fewer concert spaces hospitable toward rap than those two other major Texas cities. What’s more, a greater number of such Dallas and Houston venues have passed that critical five-year mark.

The pandemic has done a tenuous situation no favors. According to Billboard’s comprehensive list of coronavirus-related venue closures in the U.S., 54 percent of Texas’s accounted-for permanent venue shutterings were in the capital city alone (31 percent of the shuttered spaces were in Dallas–Fort Worth, while 15 percent were in the Houston area). Of these three cities, Austin is the only municipality that’s seen dedicated rap-friendly spaces shut their doors permanently.

“If a venue hangs their hat on hip-hop, there’s always a chance that it won’t last long,” says Jones. “Financially, it’s yet to prove it can generate a lot of money, and there’s no artist that has the exposure or the notoriety to pack out a venue.” Stephen Sternschein, co-owner of the Empire Control Room and Garage, a popular stage for local and international hip-hop acts alike, says that when a venue shutters, the loss goes beyond a place to play. “It’s not just the stage that goes away,” Sternschein says. “It’s also the people around it—their stories and experiences.”

“We can’t wait for the city to catch up and realize that hip-hop has been the largest genre in the world for the last ten years. It’s on us to solve these issues that we’re facing.”

As nearly every single live-music space in Austin shuttered indefinitely in March 2020, each one of them faced a grim and uncertain post-COVID future. “We sat by the bar and just cried,” recalls veteran Austin talent booker Lawrence Boone, who works at the South Austin venue Far Out Lounge. Just six months prior to the citywide shutdown, Boone and his partners had launched the spacious, three-acre outdoor stage, which sought to showcase local hip-hop acts. “We had to fire everyone literally a week after we’d won Best New Venue [at the Austin Music Awards],” Boone says. Securing financial relief from the city wasn’t easy, either; Boone, for his part, noticed that some of the required application criteria for COVID-specific venue relief funds (such as the city of Austin’s Iconic Venue Fund, which was issued December 3, 2020) weren’t conducive toward younger, rap-centric spaces. “You’d get to one page asking ‘Has [your venue] been open three years or more?’” Boone says. “Since we haven’t, we couldn’t even get past that point.”

In December 2020, Congress passed a $900 billion stimulus bill allocating about $15 billion for independent movie theaters and concert venues throughout the United States. While this bipartisan bill—which passed in part thanks to ground-level advocates such as Sternschein—is a relief, Austin music’s hardships are far from over. The unstoppable tide of gentrification continues reverberating across Austin, particularly the East Side, leaving generations of Austinites priced out of a highly competitive housing market (in 2019, nearly 5,700 Black Austin residents left for nearby suburbs including Pflugerville and Round Rock). “As Black culture and Hispanic culture shrinks,” says Jones, “it makes it hard for [the majority of local hip-hop] artists to connect.” That’s partially why a live scene that’s in the process of returning to its pre-COVID status quo can hardly be considered an improvement for the city’s artists of color. It’s also what prompted long-standing racial inequities in Austin’s music industry to reach a boiling point on the heels of Black Lives Matter demonstrations last summer.

In a Twitter thread posted on June 2, 2020, Austin-born soul-pop artist Jackie Venson called out the city’s musical movers and shakers for a lack of diversity in local concert and festival bookings. “Think about all the times a Black artist was rejected because y’all are afraid to be uncomfortable,” read part of Venson’s tweet thread. “Folks will grasp for any other reason, ‘we don’t book hip hop,’ or ‘that kind of music doesn’t fit with our crowd.’” For this same reason, Venson later rejected an invitation to perform at ACL Radio’s popular outdoor concert series Blues on the Green. (The station eventually brought together a showcase of Black Austin artists, including local rapper Randell “Kydd” Jones.) That same month, rapper Jonathan “Chaka” Mahone, vice chair of the Austin Music Commission, called for 50 percent of the city’s live music fund to support Black artists. “The city is throwing money at venues, but still working to figure out how to pay the people who fill them,” Mahone says. “If our current situation is hard for the artists who were already privileged, what about the BIPOC folks whom the scene was not set up for?”

Mahone, one half of the husband-and-wife hip-hop duo Riders Against the Storm, is one of Austin’s most influential music advocates. In late 2019, he founded the nonprofit DAWA, which has raised more than $100,000 in direct financial aid for local musicians, teachers, social workers, and other BIPOC individuals whom Mahone terms “givers.” In October, the music commission unanimously voted to recommend Malone’s proposal for dedicating half of the city-backed live music fund to BIPOC creatives.

But the rapper went a step further by establishing a separate Black Live Music Fund of his own last November, with a $10,000 starting grant from Austin’s artist-patronage nonprofit Black Fret. By awarding “smaller” direct monetary grants to Black industry workers, including promoters, entrepreneurs, and artists, the fund aims to both support local talent and create a comprehensive digital platform showcasing Black creativity via livestreamed performances and educational resources. “We can’t wait for the city to catch up and realize that hip-hop has been the largest genre in the world for the last ten years,” says Mahone. “It’s on us to solve these issues that we’re facing.”

Other initiatives, such as the recently founded advocacy coalition Black Austin Musicians’ Collective (organized in part by local hip-hop group Magna Carda) and the Black cultural district Six Square, are helping elevate Black Austin artists in the wake of COVID-19. Such efforts, combined with an ongoing citywide reckoning regarding racism in the local music industry, mean many in the scene are cautiously optimistic that hip-hop might actually get its long-overdue seat at the table. “Right now, it feels like we as a community have realized that there are doors open for us—even if those aren’t necessarily the front door,” Duke says.

With this supportive network in place, it seems Austin rap may also find the confidence to move beyond the local scene (and the college audiences) that have defined it for generations—when it’s safe to do so, of course. In the meantime, artists are making the most of uncertainty. Jalen Howard, a.k.a. J Soulja, is an East Side native who has released two full-length albums, From the Soul and This Ain’t Shxt, in quarantine. Before COVID, Howard was in the process of pivoting his popular bimonthly showcase of local talent, Smoke Out ATX—hosted by the now-defunct Scratchouse—into a SXSW 2020 showcase that would have celebrated both national and Austin-based talent. He’s since paired up with Dallas hip-hop blogger 93 Kurt Loder to rebrand the event for the digital realm. With his new online video series #BehindTheSongATX, Howard also combines live performances, music videos, and interviews into electronic press kits for upcoming artists. “One of the most vulnerable spots an artist can be in is on their come-up,” he says. “Smoke Out was my opportunity to be in the field supporting them. We’ve been privileged enough to create a following off of that physical experience to now move to digital.”

J Soulja, like many, is making the most of the move to digital. When he opened The Breaks’ virtual SXSW 2021 showcase, the rapper presented a few of his latest releases with incisive flow. He was followed by Duke’s spirited performance, which ended with her collaborator, fellow emcee and rapper J Bluuu, trading braggadocious verses from Ballsy’s finale “Only One” alongside MemeKeely, who is Duke’s wife and DJ. As the hour-long showcase quickly moved through its five performers, I was struck by the sense of accomplishment that coursed through the entire event. A year into the pandemic, and with most events happening via screens, Austin hip-hop hasn’t just survived; it’s thrived. Nothing proved this point more acutely than when Austin-based keyboardist JaRon Marshall, perhaps best known as a member of Black Pumas’ backing band, performed that night. Fresh off the heels of the Pumas’ latest Grammy nominations, Marshall and his own band’s funk-forward groove brimmed with toe-tapping energy, especially when Austin rap heavyweight Mike Melinoe made a surprise appearance, bringing his easygoing, authoritative flow to the showcase. East Austin phenom The Teeta, backed by punchy trap beats and trippy strobe lights, then closed things out with a lively flourish.

While bigger opportunities have yet to open for any single Austin hip-hop artist, a cautious optimism is materializing within the scene nonetheless, especially as venues gear up to reopen later this year. “The belief that ‘Austin just needs that one breakout star, then everyone will pay attention to it’—I don’t think it’s gonna be like that,” says rapper Charles Stephens, a.k.a. Chucky Blk. “Austin being the weird collective that it is, people are going to realize, ‘There are a lot of people making great music there, each with their own followings.’ And I would hope Austin itself hops on that train before Complex or Fader tells them to.”

Correction 04/14: A previous version of this article misspelled Cam Turney’s last name and incorrectly stated that MC Overlord was one of the hosts of Hip Hop Humpday. It has been updated.