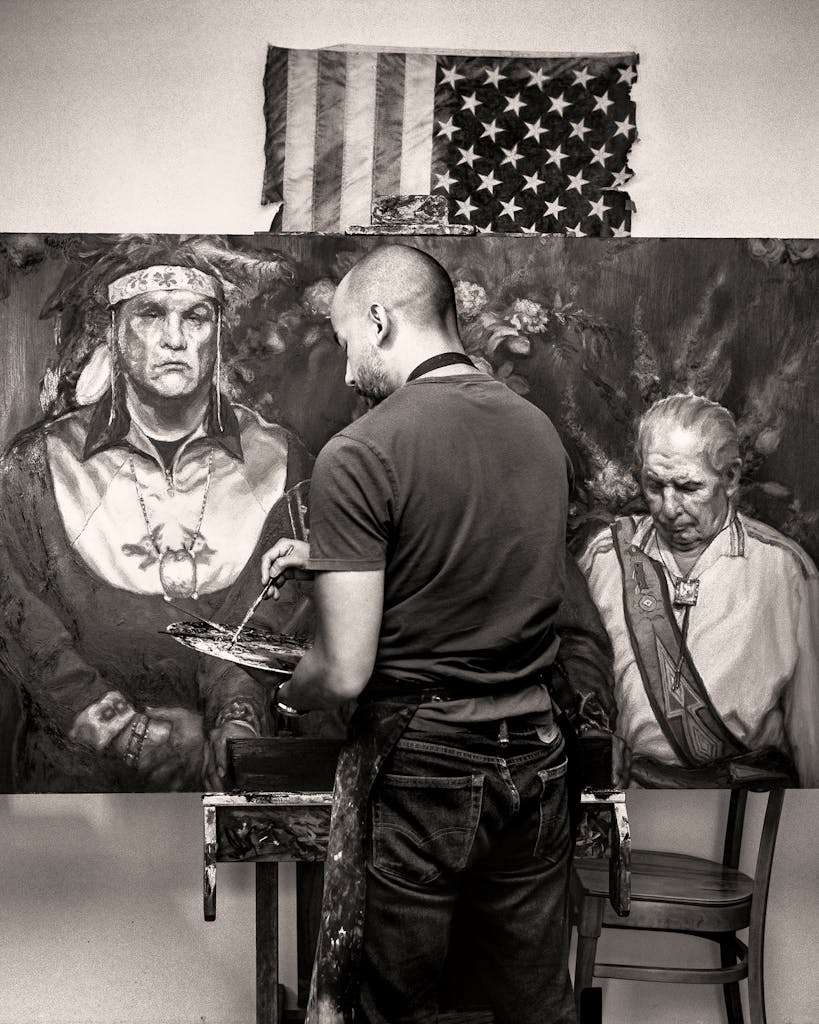

In recent months, Vincent Valdez has become Texas’s most-discussed painter. And it isn’t just his brushstrokes and eye for expressive detail that are making headlines in the New York Times, the Guardian, and a slew of revered art-world publications. For the past three years, Valdez has been immersed in a bold, high-profile attempt to confront social realities. The timing of Valdez’s project, coinciding as it does with dramatic changes in our country’s politics and public discourse, could not be more charged.

Much of the recent attention has been prompted by his epic 2016 painting The City I, a depiction of fourteen hooded Ku Klux Klan figures convening on a scrubby hillside overlooking a modern metropolis. The scene, which unfolds over five panels, spanning thirty feet in total, is set in black and white, but markers of the present day abound, including a late-model Chevy truck, a cellphone eerily glowing in someone’s palm, and a baby sporting tiny Nikes and holding a Pikachu doll. When it debuted at Houston’s David Shelton Gallery, in late 2016, the piece’s uncanny timing—just before a hard-fought presidential election that exposed deep racial fault lines—immediately attracted attention. (Valdez says the work was his “observation of something that’s always been present in America.”) The University of Texas at Austin’s Blanton Museum of Art acquired the painting—along with its companion, The City II (collectively, the works are known as The City)—for its permanent collection. After a controversial delay, the two pieces were exhibited for the first time this summer.

Despite the buzz surrounding the work, these days, Valdez’s thoughts are increasingly on his next project, a series of paintings inspired by the memorial service for one of his heroes, the great heavyweight boxer and civil rights activist Muhammad Ali. “My biggest challenge was to try to surpass The City,” Valdez says. “I feel like these do, in so many ways. But it’s hard to compete with thirty feet of painting.”

To convey the import of the new series, Valdez harks back to the afternoon of June 10, 2016, a day he remembers as hot, “both literally and metaphorically.” He was in his studio in San Antonio, where he lived before moving to Houston, putting the finishing touches on The City I, while, on a broadcast seen all around the world, Ali was being memorialized in Louisville. Little work remained to be done on The City I—some detail for the mud around the tire tracks, a bit of layering to the bright avenue lights in the background—but Valdez could not concentrate on his work. He found himself neglecting the canvas and increasingly turning his attention to what was happening on his laptop screen.

Valdez was surprised by the depth of emotion he felt watching the service, which featured a diverse range of eulogists and speakers, from a monk, a rabbi, and an imam to famous figures like Bill Clinton and Malcolm X’s daughter Attallah Shabazz. “It was really emotionally powerful, but I also realized that some of the power of that moment was, for me, being completely aware of what was looming on the horizon,” Valdez says. “Everything seemed to be erupting that summer. It was this epic moment, and the nation was about to shift drastically.”

After months of living with the hooded figures of The City I, Valdez perceived a different sort of gathering at Ali’s memorial: a meeting of those most affected by America’s inequities grieving the loss of a fighter and seeking a path forward to continue the struggle. Valdez began taking screenshots of the proceedings, trying in particular to capture the speakers in moments of reflection or when pausing to gather their emotions. He knew he’d stumbled onto something significant, as he had with the first sketches that would become The City I, a year earlier. It’s taken him two years, however, to figure out just what those feelings meant and how to express them in paint.

Valdez, who is forty, almost met Ali once, in San Antonio in 2004. Valdez had then just finished Stations, a well-received narrative series of boxing drawings that conflated a prizefight, the stations of the cross, and the brutality of life for poor men of color. Stations was Valdez’s big break; it landed him a solo show at the McNay Art Museum, in his hometown, and a traveling exhibition that went to three universities in Texas and Indiana. When he heard Ali was passing through town, Valdez says he sneaked into the Marriott hotel, hoping he could hand Ali a copy of the exhibition catalog, on which he’d written: “Thank you for helping me to see: Even when the bout is fixed, the fight must carry on.” But Valdez was stopped at the door by a bodyguard, and he never got to shake the hand of the People’s Champ.

Valdez’s connection to Ali goes much deeper than boxing. His father, Arthur Valdez, was drafted into the Vietnam War in 1970, seven years before Vincent was born. The younger Valdez has early memories of talking with his father about racial injustice during that conflict. “I was really confused but also intrigued by the stories my father shared with me about how he reported for induction,” Valdez says. “He realized that because he was a young brown man, he would likely be sent to combat. I couldn’t understand, asking, ‘Why did you go? Just don’t go!’ ”

But, as with many young men, refusing to serve was not a realistic option for Arthur, who instead begged his way into the Air Force. This led to a less dangerous but no less destructive post that, by Vincent’s description, involved loading napalm and Agent Orange onto planes, some of which were making secret flights into Cambodia.

Ali, on the other hand, was perhaps the most famous American to refuse a draft notice, telling the world, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.” Ali was convicted of draft evasion by an all-white Houston jury in 1967, but the U.S. Supreme Court eventually overturned the conviction.

As a child, Valdez became obsessed with the Vietnam War and, later, Ali’s controversial stand against it. He learned how to artistically depict both emotion and human anatomy by making drawings from a book of war photos by Larry Burrows. Valdez remembers, when he was ten, being invited to participate—along with his elementary school class—in an outdoor art project at the Esperanza Peace and Justice Center in San Antonio, led by muralist Alex Rubio. Rubio gave the precocious Valdez his own section of wall, where he painted a scene of planes dropping napalm on field-workers. The piece, which Valdez titled Make Food Not War, was quite the contrast to the rest of the students’ work, which mostly consisted of rainbows and stick figures.

In his adult studio-art career, Valdez has continued to depict forgotten episodes of U.S. history like the widespread lynchings of Mexican Americans in Texas and across the U.S. (in his Strangest Fruit series, 2013) or the World War II–era Zoot Suit Riots in Los Angeles (in Kill the Pachuco Bastard!, 2000). He likes to work with large canvases befitting the outsized resonance he hopes to invest in these buried histories. “Once you place these subjects on an epic scale, there’s no way to deny their presence,” he says. “My intention is to create public remembrance. I view these stories as my conscious observation of the world and, sometimes, my testimony of my experience here. These are visual memorials to the struggle of being human.”

Despite feared protests, The City’s debut at the Blanton this July went smoothly. The museum had originally planned to unveil the work in mid-2017 but instead kept the paintings in storage for an additional year. According to the Blanton, delaying the opening gave the museum time for careful community outreach. A spate of public programs, which included a conversation between Valdez and NPR’s Maria Hinojosa, underscored the museum’s commitment to the work. “For me, this is sort of fundamental to what we’re here for,” Blanton curator Veronica Roberts says. “It is challenging, and we are aware that it’s a really tough subject matter, but our world is tough. That’s what we’re dealing with right now. A museum sometimes feels like a sanctuary from that and a respite, and other times it’s reflecting that tumult back to us.”

“It’s not a work that we can make our peace with very easily,” adds Eddie Chambers, a professor of art history at UT who took part in the early outreach efforts. “Nor should we be able to. There are good reasons why the work unsettles us.”

Stranger than Fiction

Valdez placed a smoldering torch behind the Klansmen in The City I long before white nationalists famously carried torches at a rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.

The Blanton’s painstaking preparation prior to the debut of The City, in which leaders of the local arts and civil rights communities took part in serious discussions about the ambitions, risks, and challenges of the work, in some ways mirrors Valdez’s new series opening this month at the David Shelton Gallery. Collectively titled Dream Baby Dream, these twelve new oil paintings are all based off of Valdez’s screenshots of Ali’s funeral. Most feature a lectern with one or more silent, ruminating human figures, each an example of the racial and cultural diversity represented that day. (Ali himself is not pictured anywhere in the series.) Other paintings are still lifes. In one, the lectern is empty; in another, the lectern is gone, replaced by dying flowers under arena lights that resemble a starry sky. All shimmer with grief, anxiety, mute testimony of struggle, and a search for meaning.

It is important to Valdez that none of the portrait subjects are talking. Many wear pained expressions, looking down or to the side. “There are many conversations that aren’t being spoken,” Valdez says. “There are many words not being said. A cloud of uncertainty hangs over all of our heads right now. I think that this is a moment of reckoning, a defining moment for my generation. This country finds itself trapped, entirely trapped, between the myth of who we thought we were and the reality of who we really are.”

Dream Baby Dream is the second part of a trilogy that Valdez began with The City. Eventually, it will culminate with a third series, The New Americans—portraits of people whom Valdez says make up a diverse America. Valdez calls the trilogy The Beginning Is Near. It’s a hopeful trajectory—from the inferno of a Klan meeting through the pained purgatory of the funeral paintings to a sort of paradisiacal vision of a transforming America.

After the in-your-face shock of The City, the quiet, introspective mood of Dream Baby Dream suggests an artist reflecting on the limits and uses of art. “I don’t think that painting or art is going to change the world or that it’s going to topple governments and bring healing to people,” Valdez says. “But I am still convinced that art can provide these few moments of clarity—moments of silence—during times of immense distortion and chaos. That’s what these images do for me.

“What these images are telling me is: It’s okay to be afraid; it’s okay to be skeptical; it’s okay to be unsure of where you stand,” he adds. “What’s important is that you’re present and you’re still standing.”