About halfway through Trey Edward Shults’s Waves, high school senior Tyler Williams (Kelvin Harrison Jr.) and his stern father, Ronald (Sterling K. Brown), have a discomfiting discussion. Tyler is beset by problems at school and in his personal life—he and his girlfriend are facing a life-changing decision and he’s been abusing pain medication for an increasingly severe shoulder injury that threatens his place on the wrestling team. Tyler has begun to rebel and withdraw from his family, and his father isn’t having it.

When Ronald approaches Tyler in the family’s home office, Tyler tries to brush him off. But Ronald stands his ground, firmly reminding Tyler that, as a young black man, he doesn’t have the leeway to shirk his commitments. “We are not afforded the luxury of being average,” Ronald says as Tyler sits stiffly nearby, watching his father through watery eyes. “You got to work ten times as hard just to get anywhere. I don’t push you because I want to. I push you because I have to.”

This moment of tough love offers a glimpse at the tense dynamics at play in Waves, an emotionally intense film that follows a black family in suburban south Florida as they struggle to navigate an unexpected tragedy. The scene drew heavily from what Shults calls his “mini therapy sessions” with Harrison. The two men had previously worked together on Shults’s 2017 psychological thriller, It Comes at Night, and wanted to do so again. As Shults began working on the script that would eventually become Waves, he turned to Harrison for help. “It’s a contemporary film with a black family—and I’m clearly white,”says Shults. “I felt a lot of responsibility and sensitivity to make it real and authentic, and that’s one reason it was so collaborative.”

While Shults was writing, he and Harrison would talk about old girlfriends, their school lives, and the pressures they felt from their parents while growing up. Shults, who was raised in Spring, just outside of Houston, felt that he had a solid grip on parent-child dynamics—his father, like Tyler’s, pushed him to excel in wrestling. But he turned to Harrison to get the details of this particular family right. “Kelvin would be like, ‘If this were me and my dad, he would talk to me in this way, this is what we would talk about,’” Shults says.

The film benefits from being fleshed out by Harrison and the rest of the cast, yet there are moments in which the understanding of particular pressures on the Williamses, as a black family, feel shallow. While Ronald and Tyler’s conversation acknowledges that racial slant of the pressure Ronald knows his son will face, their struggle seems isolated. Of the meaningful relationships Tyler and his sister, Emily (Taylor Russell), have in the film, none of them are with other black people, leaving viewers to wonder how else they connect with their blackness outside of their parents. In what Shults refers to as a “baton pass,” the film shifts focus halfway, going from Tyler’s perspective to Emily’s. In the second half, we follow Emily as her family tries to stay afloat after a tragedy threatens to tear them apart. In her relationship with Luke (Lucas Hedges), there’s a healing element to their love—a welcome change from the destructive relationship between Tyler and Alexis (Alexa Demie). But it also provides an unfortunate contrast. Both Tyler and Ronald struggle to express their emotions and communicate with their partners, while Luke, a white man, is given more emotional range in the film. Even with Shults’s attempts at sensitivity, blind spots remain.

Regardless of the film’s limitations, it’s difficult not to become emotionally invested in the Williamses. “Because the family goes through some really horrible things that they have to recover from and I think it would be much easier, it would be a much easier journey if you could say, ‘Oh, that happened to those people because they are black,’” says Renée Elise Goldsberry, who plays Catharine, Tyler’s stepmom. “In this instance, what’s really beautiful and ironic is that as much space as we were given to be very specific in who we are and make the story very authentic to who we are, it still is a story that is not defined by being a black family story. It is a story of a family that’s in crisis and figures out how to keep going.” (Goldsberry, a Houston native, is best known for originating the role of Angelica Schuyler in the Broadway production of Hamilton.)

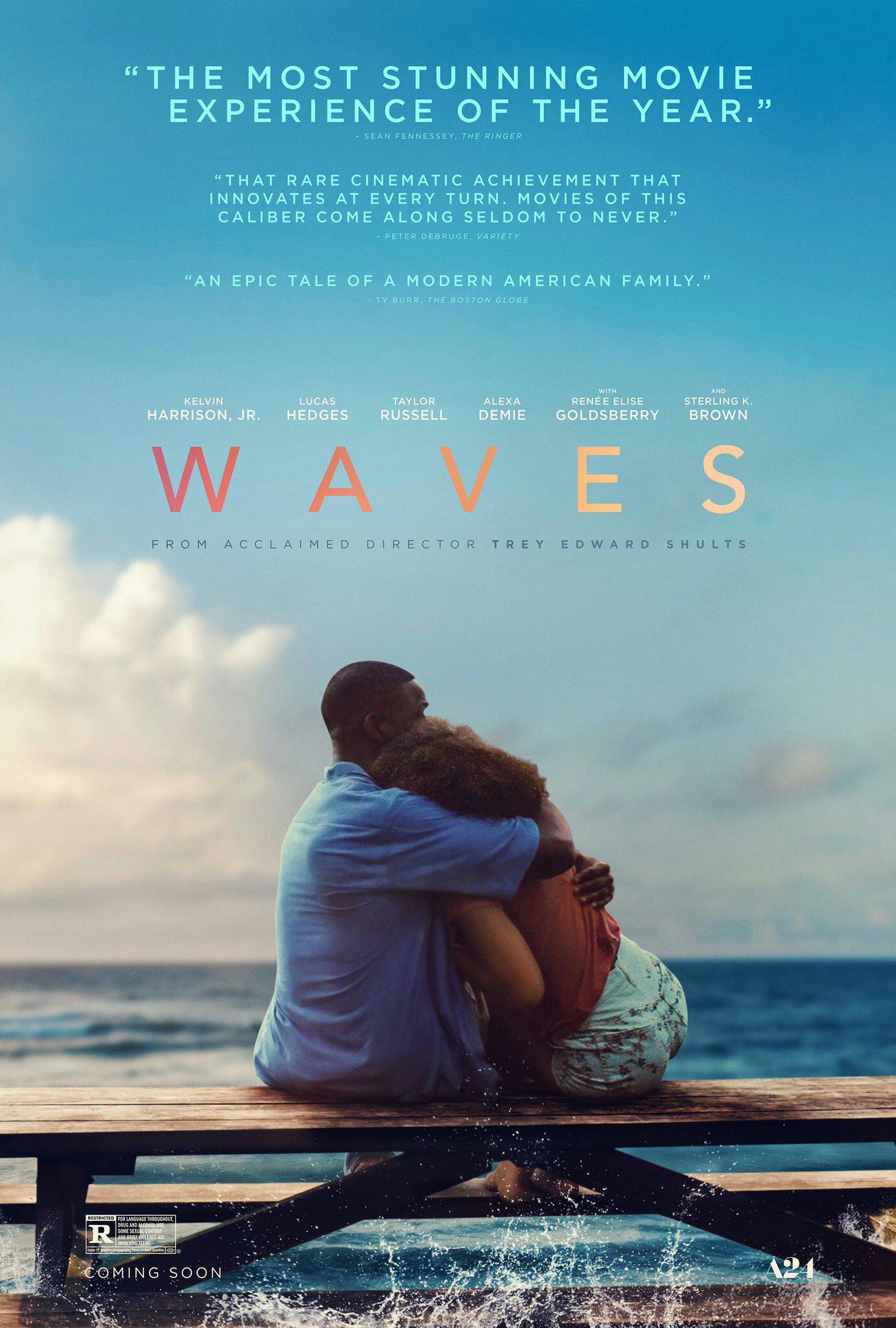

In Waves, Shults lays bare the forces that tie families together and threaten to pull them apart—a theme that dominates his films. His first feature, 2015’s Krisha, follows an estranged woman attempting to reconnect with her family at Thanksgiving dinner, only to unravel amid familial chaos. In the 2017 post-apocalyptic thriller It Comes at Night, a teenage boy comes of age at a time when following his father’s strict rules is a matter of life and death. And through its mesmeric sound design (with a score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross), moving dialogue, and beautifully shot scenes, Waves plunges viewers directly into family drama, whether characters happen to be sharing a tender moment by the water or having an emotional breakdown in the bathroom.

While Shults certainly isn’t the first filmmaker to probe family tensions, he’s unusual in that he often leaves these gnarled stories of familial drama open-ended. Rather than providing closure, he leaves viewers wondering how his fictional families find resolution—or if they do.

In fact, Shults’s interest in filmmaking began during a family gathering. When he was ten, his extended clan got together for a reunion and Shults picked up a camera for the first time and turned the event into “a weird little movie.” He kept making movies as a hobby—cops and robbers films with his friends that he dismisses as “running around and cursing at each other with toy guns.” But by the time he got to high school, he had lost interest in film. Then, not unlike the protagonist of Waves, he suffered a shoulder injury in high school that ended his dreams of becoming a wrestler. With a hole in his schedule, he signed up for a video media class. Around that time, he saw Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2007 film There Will Be Blood, which reignited his enthusiasm for film. “It blew my mind,” Shults says. “I just got obsessed with movies again.”

Shults enrolled at Texas State University with the intention of studying business management, but he only lasted a year. The summer after his freshman year, his aunt, Krisha Fairchild (who would later star in his film Krisha), invited him to Hawaii, where she was living. While there, Shults interned on a handful of commercial shoots and then got word that some of his aunt’s friends were shooting supplementary footage for Austin director Terrence Malick’s documentary Voyage of Time: Life’s Journey. Shults got hired as an intern on the project even though he had little filmmaking experience.

Through a series of lucky breaks Shults was soon promoted to the role of film loader. His boss was so impressed with his ability to learn quickly that he invited Shults to other shoots with Malick’s crew. “I was like, ‘I’m not going back to school. I’m going to see where this goes,’” Shults says.

Observing Malick’s unconventional approach inspired his own maverick tendencies. “One thing I caught on pretty quick is that Terry is so unorthodox and so Terry that it would have been stupid for me to try to do the same exact thing he does—only he can do that,” Shults says. “It was like he cracked how to fully be him. He’s a legend. And then I thought, ‘I wonder if I have something like that? Can I try to find a way of doing something that only I could do?’”

Spurred by that moment of clarity, Shults spent the next few years making a couple of short films, learning more about his craft with each one. In between projects, he would return to his mother’s home north of Houston, helping her and his stepfather, both of whom are therapists, with their business and doing handiwork around the house. He set up a sort of private film school in the family’s TV room, teaching himself how to make movies by watching films and studying film books.

Shults’s first attempt to make a feature film didn’t go so well. “I failed miserably, and I knew it while I was doing it,” he says. “We were getting some beautiful things, but some things weren’t working. I was like, ‘I do not have a movie here.’” He decided to condense it into a short film, and spent two years editing it: that became Krisha, a short movie about a woman who tries to revitalize her relationship with her family after spending a decade away from them. It premiered at South by Southwest in 2014.

Energized by the short’s acceptance into the festival, he took another shot at making a feature-length version of Krisha, and filmed it in nine days at his mother’s house with a cast almost entirely composed of family and friends. The next year, it won both the Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Award at South by Southwest, was nominated for the Nespresso Grand Prize at Cannes Film Festival, and landed Shults a deal for two features with the production company A24.

Waves is the most fully realized and deeply felt work of Shults’s three films, perhaps because it comes from an intensely personal place. Nearly twenty years ago, Shults lost contact with his biological father, who struggled with addiction for years. Then, in late 2011, after the two hadn’t spoken for a decade, he got word that his father was dying. Shults was reluctant to see his father at first, even though it might have been his last chance to do so. But his girlfriend persuaded him to make the trip, so Shults traveled to Missouri to say goodbye. “Losing him in the way that all transpired was a very impactful moment in my life,” Shults says. “So it’s something I keep going back to.”

Shults’s gnarled relationship with his father has worked its way into all of his movies. In Krisha, the title character’s estranged son—played by Shults—barely looks at her throughout the film; at one point, he refuses to claim her as his mother. It Comes at Night, which he wrote while grieving his father’s death, also explores the tension between a father and a maturing son, heightened by their need to survive an unnamed pandemic. And in Waves, one character goes on an extended trip to say goodbye to his own estranged father, who is dying from cancer—a sequence that draws directly on the most affecting episode in Shults’s life.

In this sense, Waves marks the end of the story Shults has been writing for years. “I feel like a blank slate now,” he says. “I put everything into this movie.” But he believes there will be other stories to tell in the future. “I don’t have children or anything,” Shults says. “Hopefully I can live some life and loved ones can live some life, and I’ll have a new personal movie somewhere ten years from now.”

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Terrence Malick

- Houston