Featured in the Houston City Guide

Discover the best things to eat, drink, and do in Houston with our expertly curated city guides. Explore the Houston City Guide

You must not go to London, Paris, or New York to be cosmopolitan. Just open your ears and your eyes and you have it, right in Houston. —John de Menil, 1949

You must understand: for those who are deeply involved in the Houston art scene, it is heresy to suggest that the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, is in any way superior to the Menil Collection. The Menil is our sacred cow, unassailably world-class, frequently described with the word “jewel.” Founded in 1987 by the European émigré Dominique de Menil, who, with her husband, John, dominated Houston’s evolution into a serious art city, the Menil is our pride and joy.

By contrast, the MFAH is still associated with the populist, unabashed hucksterism of its late longtime director Peter Marzio. Marzio made serious art lovers cringe with lowbrow shows about Star Wars and the Houston Texans football team—the latter when the team’s owner, the late Bob McNair, was a museum trustee. During the Marzio years, from 1982 until his death at age 67, in 2010, it sometimes felt as if the MFAH had a “For Rent to Highest Bidder” banner duct-taped to its side.

But the past decade has felt like watching one of those interactive time-lapse bar charts where one bar shoots up and the other one wavers. The MFAH has vastly improved, while, more and more, the Menil seems to be joylessly treading water.

Of course, this isn’t a completely fair comparison. The MFAH is one of the largest museums in the world and, in the U.S., second only to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in terms of square feet of gallery space. Its $1.7 billion endowment is the fourth largest in the country. Founded in 1900, it’s by far the oldest and richest museum in Texas, with a campus crammed with exorbitantly expensive “starchitect” buildings (its recent additions, the Glassell School and the Kinder Building, together cost about half a billion dollars). It is meant to be an encyclopedic museum with collections across the full range of human cultures and eras. Many, many donors (including the de Menils) have added to the MFAH’s collections and enriched its coffers over the years.

By contrast, the Menil Collection reflects the singular passion and idiosyncratic vision of one couple. It’s a much smaller, younger institution—today it has an endowment of $376 million, roughly a fifth of the MFAH’s. Prior to the pandemic, the Menil hosted about seven exhibitions a year. The MFAH hosted about fifty. But despite its formidable size, the MFAH often felt like the city’s also-ran.

The reasons for this are historical. For decades, John and Dominique de Menil were major arts patrons in Houston, supporting at various times the MFAH, the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, St. Thomas University, and Rice University. After John’s death in 1973, Dominique continued acquiring art and building support for a stand-alone museum for their holdings. When the Menil Collection opened, it single-handedly elevated Houston’s profile. For one thing, there was its extraordinary collection of objects, which included ancient artifacts, medieval icons, a handful of Renaissance and Baroque European paintings, Indigenous art (including African, Oceanic, and Pacific Northwest art), and twentieth-century art. Small but mighty, it was a visionary, cherry-picked survey of humanity’s most enduring spiritual and aesthetic concerns. Walter Hopps, the legendary founding director of the Menil, referenced the collection as a set of archipelagoes or islands. He added, “It encompasses the reach of the largest art museums but maintains no imperative for inclusiveness,” an assertion of eclecticism with a faint whiff of hauteur, which has always been a hallmark of the Menil.

As for the building, designed by Renzo Piano, it’s a near-perfect union of local architectural vernacular and exquisitely placed galleries. Its cypress siding, pine floors, and big dogtrot hallway incorporate what is most cool and functional about traditional Houston architecture into a relatively unobtrusive profile. Dominique de Menil famously requested that the building appear small on the outside but large on the inside.

By contrast, the MFAH’s campus is a motley mess of form over function. The original 1924 neoclassical building, designed by William Ward Watkin, is barely discernible anymore except for its south facade, which ignominiously faces a traffic roundabout. Two additions to that building, both by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (in 1958 and 1974), now known collectively as the Law Building, are generally agreed to be some of the finest examples of Modernist architecture in Houston. But they aren’t great for displaying art: museum staff often must erect temporary walls to make use of the Mies additions, as the museum generally does. The Beck Building, built in 2000 and designed by Rafael Moneo, has some nice galleries, but its turgid lobby flanked by a big escalator has always reminded me of Houston’s old Sakowitz department store. And the new Steven Holl–designed Kinder Building, which opened in November 2020, has a hopelessly ugly concrete lower level; a bombastic, Hyatt hotel–style atrium encrusted with terrazzo; and free-flowing galleries that critics have compared to being funneled through IKEA. It is not a perfect building.

And yet, when I first visited the Kinder Building’s inaugural installation, and on the many occasions I’ve returned since to look at all the remarkable art packed in there, I have enjoyed myself. And that’s the key: I have fun visiting the MFAH campus these days. The place feels optimistic and alive and deeply human. And—lest we forget—none of it, warty buildings and all, would have been possible without the fund-raising acumen and shrewd strategy of Peter Marzio.

The ultimate test for me was whether or not I wanted to tap my neighbor on the shoulder and say, “Look at that.” —Peter Marzio, 2009

During Marzio’s 28-year tenure as director, the MFAH was not known as an exhibiting powerhouse. In addition to the aforementioned “Star Wars: The Magic of Myth,” in 2001, and “First Down Houston: The Birth of an NFL Franchise,” in 2003, Marzio oversaw other stinkers. There was “Diamonds Are Forever: Artists and Writers on Baseball,” in 1989, and at least ten “Treasures of [insert any culture, the more exotic the better, whose jeweled gewgaws were rented out for a road show].” When the museum featured actual art in its temporary exhibitions, it often played it safe. There were three Jackson Pollock shows, four Picasso shows, and an eye-popping seven Jasper Johns shows during Marzio’s tenure. Of course, there were ten exhibitions of Impressionism.

It was easy to observe this and assume that the MFAH was bush-league. But Marzio, a scrappy New York transplant who was the first member of his working-class Italian family to finish high school, was warm and savvy, and he had a genius for reading the landscape. Houston was becoming more diverse, and he capitalized on that. Most notably, he spearheaded the MFAH’s Latin American department, which today dominates the field nationally, thanks to the leadership of curator Mari Carmen Ramírez, whom Marzio poached from the Blanton Museum of Art, in Austin. He initiated an Islamic department and carved out dedicated galleries for the MFAH’s small but growing collections of Asian art. He aggressively collected important early works by the self-taught artist Thornton Dial and other African American artists (sometimes overcoming the reluctance of trustees). He championed the legendary Gee’s Bend quilt exhibition, which was curated by Alvia Wardlaw in 2006. And as for European art, he secured several donations of major collections.

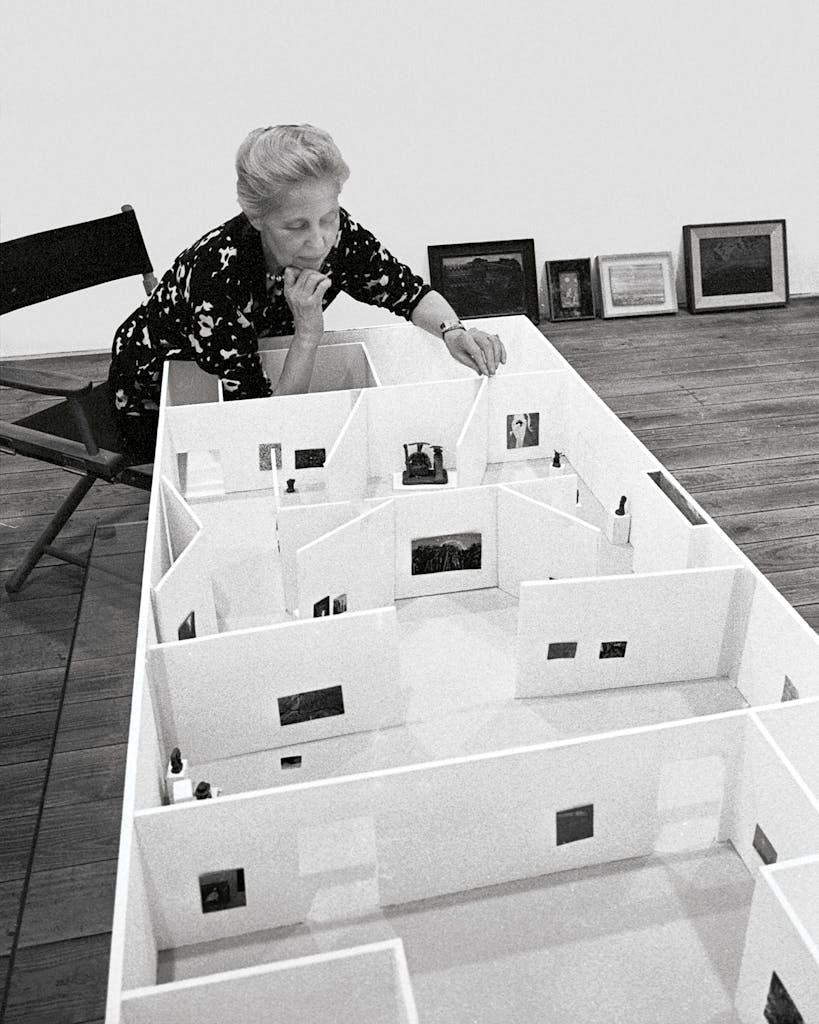

Marzio also had a clear long-term vision for the MFAH campus. The museum added the Isamu Noguchi–designed Cullen Sculpture Garden in 1986 and the Beck Building in 2000. Critically, he acquired the land for the Kinder Building, which at the time was a parking lot owned by First Presbyterian Church. (Marzio kept a 3D model of the neighborhood in a meeting room adjacent to his private office, with lots earmarked for future growth—even those not yet owned by the museum at the time.)

But more than anything, the man could raise money.

During his directorship, the MFAH’s endowment increased a staggering fortyfold, from $25 million to over $1 billion. That increase was due mostly to an extraordinary bequest from Caroline Wiess Law of some $450 million, likely the largest single gift to an art museum in the U.S. (the Met’s largest gift, by contrast, has so far been $125 million). Marzio cultivated Law’s friendship and patronage for decades, and she left the bulk of her estate, along with dozens of artworks, to the MFAH. Crucially, half of her bequest was set aside for post-1900 accessions, giving the MFAH one of the largest endowments for modern and contemporary art and freeing up other funds for historic works.

But despite Marzio’s inarguable success as a director, the MFAH never enjoyed the reputation of a top American museum during his tenure. Maybe it was the uneven exhibition program. Maybe it was his focus on cultivating Houston donors rather than the international professional museum elite. Regardless, after Marzio’s death, in 2010, the war chest he accumulated was put to work. Staff size didn’t grow tremendously (a current curator describes it as “lean”), but the Law bequest went toward a decade-long buying spree for artworks that remained mostly hidden in storage. Until now.

The opening of the Kinder Building under the guidance of director Gary Tinterow, who succeeded Marzio in 2012, was the most exciting museum event in Houston since the opening of the Menil. The Kinder’s galleries were crammed with fantastic objects I had no idea the MFAH owned. “Crammed” is the operative word here—the museum embraced what you’d call a dense hang, with objects packed on gallery walls. When I pointed this out to a local academic, he sniffed, “MoMA has been doing that for years.” But so what? It was thrilling to see the MFAH hold nothing back: a spectacular wall hung floor to ceiling with dozens of photographs, Modernist rooms filled with surprises, a gallery with abstract works all about skinny lines (“They out-Meniled the Menil,” a friend commented, referencing the Menil’s tradition of minimalist austerity). Best of all, artists from Houston and elsewhere in Texas were included throughout the museum, not clumped together in a “Texas ghetto” side gallery. The hardest thing of all is to appreciate what’s in your own backyard.

But the Kinder wasn’t the only exciting change at the MFAH. Shortly after the Kinder’s opening, the museum reimagined the American galleries downstairs in the Beck Building. The new installation, which spotlights Native American objects and inventively mixes art and design, is a triumph. The museum’s temporary exhibitions have been strong too—the recent “Afro-Atlantic Histories” and 2018’s “Peacock in the Desert: The Royal Arts of Jodhpur, India” were both standouts. The MFAH isn’t stopping, with plans to unveil expanded Islamic galleries later this year, overhaul the European galleries upstairs at the Beck, and completely reinstall its African holdings. And the MFAH’s World Faiths Initiative, the brainchild of Tinterow, will promote the spiritual function of artworks and emphasize the commonality of various faiths—something the deeply Catholic Dominique de Menil always emphasized in the projects she championed.

What is art if it does not enchant? —Dominique de Menil, 1987

And the Menil? While the MFAH was working on an overpriced new building, the Menil was actually doing the same. The Drawing Institute building opened in late 2018. It reportedly cost $40 million, or more than $1,300 per square foot, and most of it houses a research center that is open to the public only by appointment. The Drawing Institute is everything the original Menil building is not: it’s luxuriously expensive, with extra-wide European oak floors, as opposed to the humble pine in the main building. Its galleries are small and unremarkable. It contains a secular monastery of drawing scholars in big, chic offices viewable through glass—you can see the scholars, but you can’t touch them! Also, the institute’s storage is mystifyingly located in the basement. Since the next catastrophic flood in Houston is not an if but a when, that makes the basement essentially a building-size bathtub complete with a large room of pump equipment and state-of-the-art floodgates.

So the Drawing Institute, like the Kinder, is lavish and not terribly functional. But unlike with the Kinder, its exhibitions haven’t saved it from itself. When the plans for the institute were originally announced, in 2008, curator Bernice Rose put together “How Artists Draw,” a brilliant, revelatory group show in the main building. I assumed there would be something similar for the institute’s opening, but instead came four solo shows in a row, starting with Jasper Johns, a safe and predictable choice. More recently, there have been small, thematic group shows that are better but still not setting the world on fire. The best so far, “Silent Revolutions: Italian Drawings from the Twentieth Century,” was mostly a visiting collection.

Safe and predictable: this is the Menil Collection today. The spare installation style of Dominique de Menil, who died in 1997, feels dated and overly fastidious. The once-thrilling installations of twentieth-century art have devolved into matched groupings—here is the Warhol silk-screen hallway, here the Barnett Newman room, here the corner of Cornell boxes. The twentieth-century galleries are dull, but particularly disappointing are the Surrealist galleries, which were once dark, fanciful caves. They have been repainted a lighter gray, and the paintings in them are often grouped by artist and installed in an orderly march around the rooms.

True, the recent Niki de Saint Phalle show was a wacky, long-overdue homage to an artist who was included in the original 1987 Menil catalog and deserved a closer look. But that came on the heels of “Allora & Calzadilla: Specters of Noon,” a bloated, nonsensical installation of massive sculptures that made the Menil look like a mega gallery, in service to the art market, not to art.

The old magic is still there in pockets, particularly the galleries of ancient and African art. But overall, the Menil Collection feels calcified, in thrall not so much to the ideals of its founders but to the idea that its founders had irrefutably correct ideals. The religiosity and reverence afforded to it are a phantom limb felt by every Houstonian who cares about art, but until something changes, the MFAH has, improbably, become the keeper of the Menil spirit of inventiveness.

And so, what would Dominique de Menil do? This is the burden of any institution that loses a visionary founder. The good news is that the collection is still there. The building is still there. And Dominique’s embrace of the fanciful, the mythical, the enchanted, can always be rekindled. It is easy to imagine the Menil shaking off its solemnity and running amok in its wonderful holdings. It is easy to imagine the Menil once again putting things from its collection together in unexpected and delightful ways. It is easy to imagine the Menil—the brilliant, iconoclastic Menil—having fun again and welcoming all of us to the party.

Rainey Knudson is an arts writer in Houston. She recently edited One Thing Well, a book about the Rice Gallery, and is now editing a book about Texas art since 2000.

This article originally appeared in the March 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Changing of the Garde.” Subscribe today.