There was a time when Will Johnson might have been the most prolific musician in Texas. “I don’t think I’ll ever get to create all the music I want to create,” he told this magazine in 2012, and the numbers show it: between 1999 and 2008 he released a staggering twelve full-length albums, one of them as a double CD. These came out under many different names, from Centro-matic’s full-band fuzz-pop to South San Gabriel’s collaborator-heavy orchestral-country sound—or, when particularly lo-fi and spare, as a solo record.

Johnson’s been at this for some time. He was a key part of Denton’s indie music scene, got and then lost a major label contract as the drummer for Funland, and built bridges out to the rest of the country through Centro-matic’s relentless touring schedule. All this work brought Johnson a small and devoted fanbase, particularly among fellow songwriters. His Brillo-scratched voice and way with a chord change made him the secret weapon in many collaborations, from the record he cowrote with the late Jason Molina to Overseas, his supergroup with David Bazan and the Kadane brothers. Jim James recruited him to play drums and sing backup with Monsters of Folk, and then brought him along as a partner in his Woody Guthrie tribute project, New Multitudes. To keep up with his full output has been an unlikely and disorienting proposition.

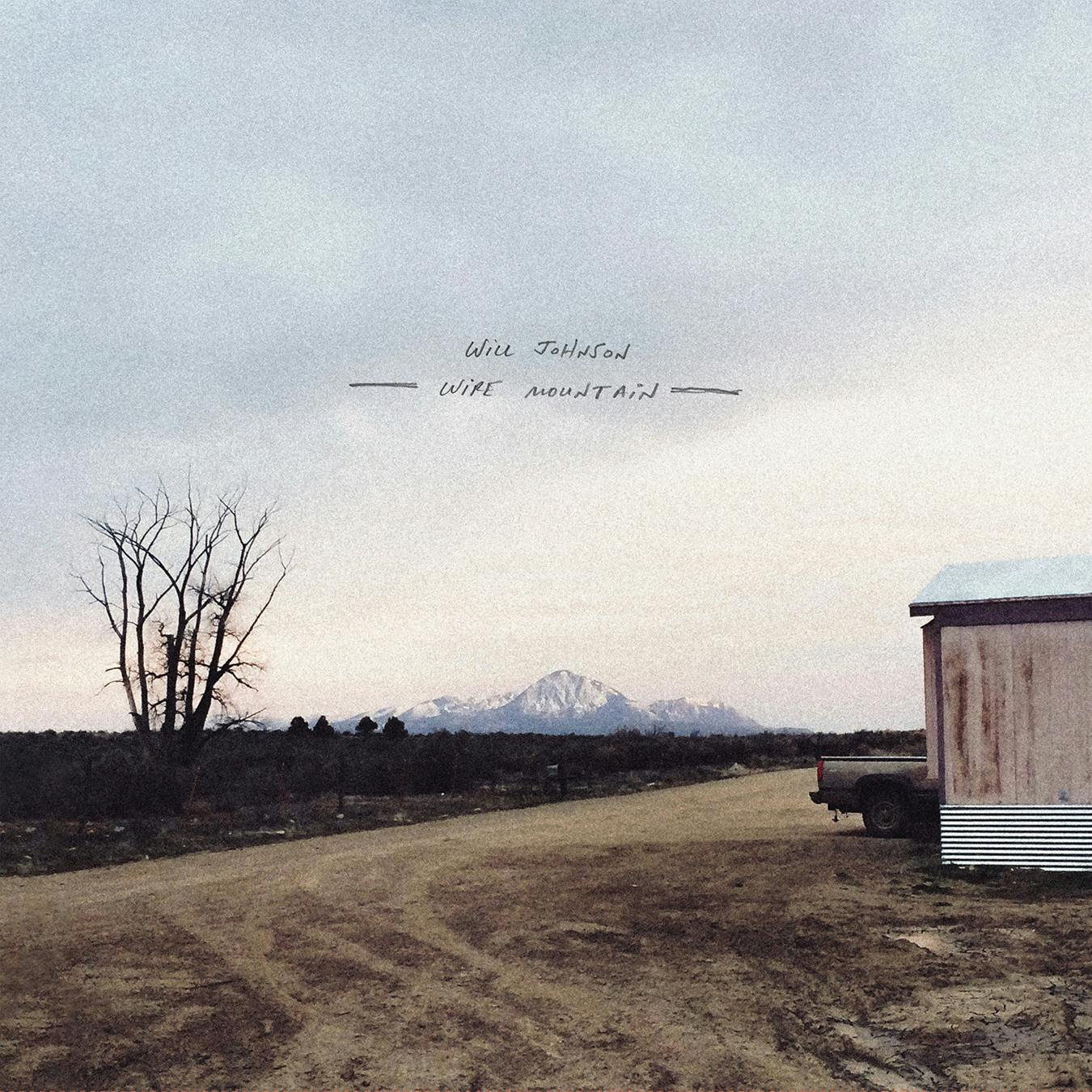

Nowadays, Johnson seems to be taking his time. His new album, Wire Mountain, out on September 27 under his own name, is only his third since Centro-matic’s 2014 breakup. His earlier solo records felt full of songs that just didn’t fit anywhere else. But Johnson’s work post-Centro-matic, particularly 2017’s excellent Hatteras Night, A Good Luck Charm, is indisputably the best and most patient of his career, the work of an artist more comfortable than ever holding something in reserve.

That’s partially due to his changing vocal approach. On those nascent records, you got the sense that Johnson was straining to convey something important with his prematurely scratchy voice. But Johnson has aged into a remarkable singer, allowing his deeper range—and particularly his skill as a harmonizer—to do the real work. Songs like “Need of Trust and Thunder” get incredible mileage out of a few notes and his ability to make a melody sound slightly different on each repeat. Even when he gets loud, as on opener “Necessitarianism (Fred Merkle’s Blues),” Johnson leans into a downbeat and even mournful register. He no longer has to yelp to get his point across. The excitability may have gone, but Johnson’s sense of conviction remains.

Wire Mountain luxuriates in these kinds of details, from the resonance of a distorted guitar to the way a mallet makes a tom head sing. “A Carousel Victor” approximates slowcore, allowing big, fuzzy notes to hang in the air as Thor Harris (of Shearwater and Swans) and his drums fill in the gaps, before rupturing it all with a Crazy Horse coda. “A Solitary Slip,” meanwhile, is tender on the surface, and allows its hymn-like insistence on “a mother’s love” to hold off the menacing hum that frays the song’s edges.

Johnson’s collaborators from the Austin scene shine here, too. Harris gives even the tender “Shadow Matter” an insistent backbone, containing its jammier moments. Though built around Johnson’s guitar, “Gasconade” really comes to life in the extended back stretch when Little Mazarn’s Lindsey Verrill skates around the circular chords, a one-woman orchestra of scraping cello strings and haunting banjo that slowly swallows up the song. Texas alt-country legend Jon Dee Graham even shows up to close “Cornelius” with a ripping slide guitar solo.

By keeping the frame tight—fewer collaborators, shorter track lists, one album every couple of years—Johnson turns your focus to what makes his songs work so well. You feel the consideration of every melody, harmony, and word choice, now hearing the space which older arrangements would have felt it necessary to fill. Like the works of Marfa-based photographer Matthew Genitempo (which have graced his last few covers), Johnson’s music invites you to look long and hard to determine what might—or might not—be there.

These days Johnson seems to be readjusting the frame around his own life. His tours consist largely of Living Room Shows for existing fans, he releases albums on regional and boutique labels, and his songs eschew traditional choruses for texture. These days he spends as much (if not more) time painting and raising a family in Austin than out playing music. How many parents, after all, can afford to spend the better part of the year on the road? How many even want to?

But as Johnson’s solo work shows, this careful consideration can act as its own creative force. Patience isn’t always a quality that we associate with music. On Wire Mountain, Johnson makes the case that we should.