Like millions of Americans, William Basinski was shattered by the events of September 11, 2001. But for Basinski, that day bears further significance. While most watched the horror unfold on television, the Texas-born musician and composer witnessed and filmed the devastation from the rooftop of his Brooklyn loft, while, in the background, his speakers blared his newest work, The Disintegration Loops, which he’d finished the month before. He didn’t know it yet, but TDL would come to be regarded as one of the most important works associated with 9/11—and would transform him from an obscure musician into one of the most revered experimental composers of the young century.

TDL, made up of brief samples of old Muzak recordings playing on loop and decomposing (literally) with each repetition, is hypnotizing and evocative, an unlikely masterpiece. The five-hour work, which has been named one of the greatest ambient albums of all time, has been arranged for symphonic instruments and performed by an orchestra at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A one-hour excerpt of TDL set to Basinski’s film footage was added to the collection of the National September 11 Memorial & Museum.

With the twentieth anniversary of 9/11 drawing near, Basinski will (COVID precautions permitting) perform concerts across the country to revisit the work—and the national tragedy—that changed his life. Before 9/11 he had spent decades fruitlessly trying to get people to listen to his music; after 9/11 he became a star of the avant-garde. It wasn’t the first time he found that trauma and creation are often bound together.

“I wanted to be a rock star since David Bowie happened,” Basinski says, sitting poolside at his home in Los Angeles, where he’s lived since 2008. He’s well put together, in a half-buttoned white shirt and skinny black jeans, with silver rings on his fingers and his dirty-blond hair in a loose ponytail, and he’s quickly working through a pack of American Spirits. Basinski’s Catholic upbringing is evident when he credits Saint Cecilia with finding him his house, a mid-century classic designed by postwar architect Edward Fickett.

Basinski was born in 1958 to a big, sprawling Texas family. “We played a lot of music in the house,” his father, 91-year-old Erwin Basinski, recalls over the phone from his home in San Jose, California. “My wife played piano; I played trombone. We always had the radio on.” They instilled that love of music in their five children: firstborn Mark studied classical and jazz guitar; Billy—as the family still calls him—gravitated toward clarinet and saxophone; Peter played trumpet; Anne studied voice; and Patrick, like his father, chose trombone.

Erwin’s various technical jobs led the family to move often; they did stints in Texas, Virginia, and Florida. “It was almost like an Army brat kind of childhood,” Mark says. It wasn’t until the early seventies, when Basinski was a teenager, that the family finally settled down in Richardson, just outside Dallas, where Erwin worked for a telecommunications software company. By that point, Basinski felt different from his classmates. When Bowie’s audacious glam rock broke big in America, the star’s androgynous, sexually charged alien persona immediately resonated with the young Basinski, who began dressing in skintight denim bell-bottoms and platform shoes. His cousin Christopher Smart recalls his own family driving up from San Antonio to visit the Basinskis. “Total straight, white-bread early seventies,” he says of the Dallas suburbs. “But Mark looked like Frank Zappa, and Billy looked like Ziggy Stardust.”

Basinski bristled against the repressive mores of his social environment. “You could have the experience of some redneck grabbing you by the hair and yanking you around,” Mark says. “I definitely had that experience.” Basinski found some solace in music, playing saxophone and clarinet as a student at Richardson High School. But even in a musical household, according to Smart, “Billy was the black sheep of the family.” I ask Basinski if he clashed with his parents, and the normally effusive artist falls silent for a full minute before responding. “Mother and I had issues which were hard on me,” he admits.

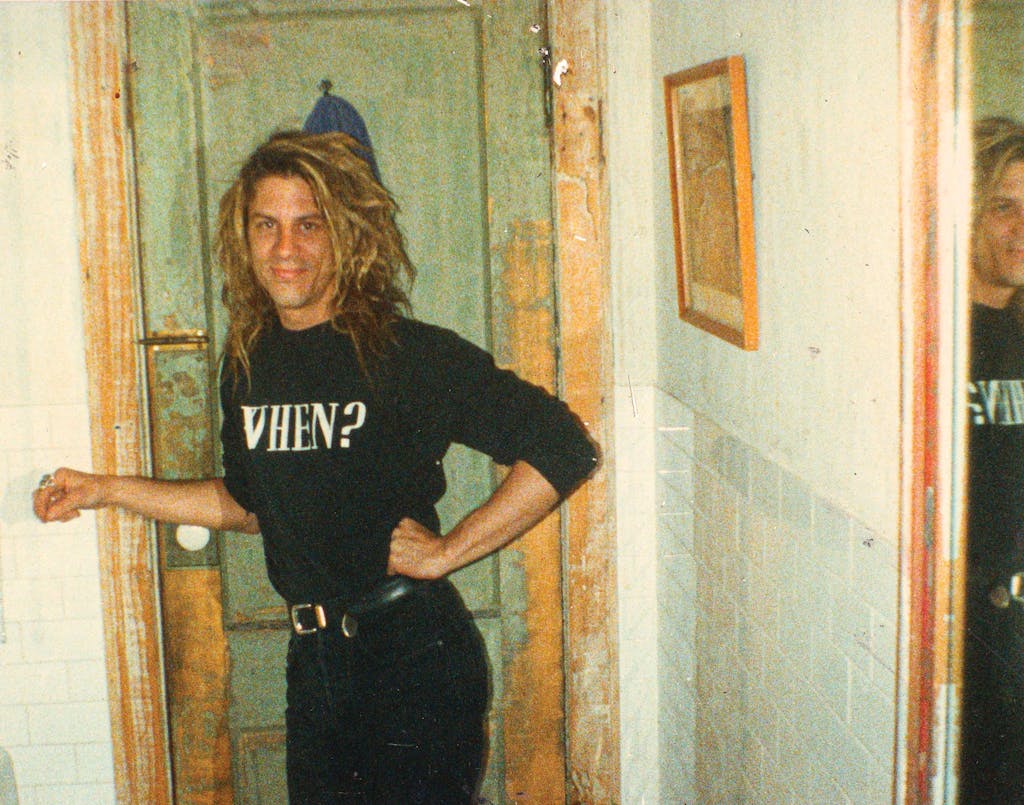

After high school, Basinski studied music composition at North Texas State (now the University of North Texas). In one course, Basinski learned about composer John Cage and mindful listening: to the birds, the cicadas, the distant highway. But more than the curriculum, Basinski fondly remembers Denton’s heyday as a countercultural hotbed, with “acid on the street, mushrooms in the fields.” His classmate David Weyrauch had Basinski model for some photographs clad in an Air Force flight suit and mirrored aviator sunglasses, his coif reminiscent of Bowie’s in the 1976 Nicolas Roeg film The Man Who Fell to Earth.

When Weyrauch visited his friend James Elaine in San Francisco a few months later, he shared the photo of Basinski, and Elaine was smitten. “I didn’t know who he was, but I kind of knew what he was,” Elaine says over the phone. Raised in Dallas, Elaine had recently graduated from North Texas State himself and had decamped to San Francisco to pursue an art career. He returned home in October 1978 to visit friends, not knowing if he would cross paths with that model. “I walked into Kennedy’s Saloon, and there he was, and that did it,” Elaine says of meeting his life partner for the first time. Less than two weeks later, Basinski dropped out of school and flew to San Francisco to be with Elaine.

“I don’t know when Billy came out [as gay], but he was ostracized,” recalls Smart, who today plays bass, collaborates with the Texas chanteuse Chrystabell, and owns the San Antonio music store Robot Monster Guitars. “No one in the family was in touch with him.” (Basinski says it was more of a self-imposed exile and that he remained close with an aunt in California.) At one point in San Francisco, Basinski says, he wrote a letter to his mother cataloging his hurt, “every humiliation, every heartbreak. I never sent it. But it was such a therapeutic thing for me to do. We’re so much alike; we’re very connected. After that, that’s when I started making these melancholy tape loops. I was able to put all of that into the music. It healed me.” Years later, the two reconciled, and they remain close.

While Elaine worked on his paintings, Basinski toyed with recording tape and electronic equipment. A tape loop is, as its name implies, a strip of magnetic tape fastened into a circle that plays a melodic or rhythmic figure ad infinitum. The Beatles used tape loops on “Revolution 9,” and most modern hip-hop producers use a similar technique, employing digital technology rather than a fragile strip of tape. Inspired by the ambient tape loops of British glam rocker turned producer-composer Brian Eno, Basinski began experimenting with the sounds he heard all around him: cable cars, old refrigerators, radio signals. “You put a microphone in the freezer, record it on high speed, turn it down to half-speed, and it’s like, ‘Okay, we’re in outer space,’ ” Basinski says with a hearty laugh.

In 1980 Basinski and Elaine moved to New York City. “We just were in love with each other,” Elaine says. “My paintings became his music, and his music became my paintings. We were constantly working. We were like our own Andy Warhol Factory.” When Smart reconnected with his older cousin during a visit there a few years later, he found someone living on his own terms and thriving amid the energy and anonymity of a big city. “It was life-changing to see this whole other world where you can live however you want, create your own environment.”

Ambient music first became popular thanks to Eno’s classic 1978 album Ambient 1: Music for Airports. Its liner notes stated that the genre should “be as ignorable as it is interesting.” Since then, it has evolved into a tangle of subgenres including new age music, but also yoga-class soundtracks, Spotify offerings of “celestial white noise” to aid sleep, and YouTube streams of “chill lofi beats to code/relax to.” Though some listeners find it maddening, others regard it as a source of comfort and succor.

By the nineties, Elaine and Basinski were living in an enormous art space in Williamsburg that they dubbed Arcadia. Basinski worked all manner of odd jobs—hanging drywall, cutting hair, managing a fashion photography studio. He opened a vintage goods shop and played saxophone on friends’ albums but struggled to get his own ambient compositions noticed. A demo sent to Eno received no response, disheartening Basinski further.

“Billy’s world had a very specific sound, and it smelled of antiques, car oil, fresh coffee and cigarettes and freshly squeezed orange juice,” remembers his friend Anohni, the Mercury Prize–winning singer-songwriter. While Anohni was living in New York and striving to develop her own music, she found solace in Basinski’s sound world. “It was always playing—quite loudly—throughout Arcadia,” she remembers. “It was like an ocean that was washing through the space, insisting on a different kind of social frequency. I would lay on his feather bed for hours, just sort of taking refuge.”

Calming as his music might have been, by 2001 Basinski found himself in a deep depression: “I was at the end of my rope, figuring nobody was ever going to get my music.” He was forced to close down his store at the start of the year and racked up more than $30,000 in credit card debt. He had started releasing ambient works on a European label, but outside of a small circle of friends, few people heard them. By his estimation, he has hundreds of tape loops, “boxes and boxes” of them, stored in “ice cream containers, takeout bins, and stuff.”

In July of 2001, he stumbled upon some tape loops he had made twenty years earlier, recordings of music aired on an old Muzak radio station. The tapes, he remembered, “had been set aside because they were so perfect.” He decided to digitize them and set about loading the first loop for playback. “When I put the first one on, I was like, ‘Oh, God, do I ever need this now!’ ” It was easy-listening music slowed down until it was solemn and eerie.

He stepped away briefly to make some coffee, and when he came back, he realized that the recording machine was causing the original tape’s metal oxide coating to flake off, an archivist’s worst nightmare. What he had captured decades earlier was now dissolving back into the ether, the anonymous orchestra slowly replaced by crackle, static, glitches, and dead air. But rather than hit stop, Basinski let the recording keep going until the original loop had completely disintegrated.

Years before, Elaine was a curator at New York’s Drawing Center when a pipe burst in the basement, ruining thousands of old books. Rather than dump them, he lugged hundreds of the sodden, mildewy books home on the subway and incorporated them into his paintings. “Through decay, they became more beautiful than the original books, in my opinion,” he says. Integral to the creative process, according to Elaine, is remaining open to possibilities: “You’re on the right path when you’re open to mistakes. You have to be open to failure.”

Likewise, rather than react with horror at his archival failure, Basinski decided that he had created something new and sublime. That afternoon’s recordings became the first of four volumes of TDL, each made up of an old Muzak tape loop that he allowed to flake off as it played. “That’s Billy,” his brother Mark says. “It wasn’t like ‘Oh my God!’ and pressing stop. He had the presence and the vision to go, ‘This is the art’ and just let it happen. That is his real brilliance. Most other people would have pressed stop on that tape.” Anohni remembers Basinski “called me up in a frenzy of excitement because these old tapes he was playing were falling apart.” She shared in his excitement, “but [Basinski] couldn’t imagine a way for it to reach the broader public.”

On the day Basinski watched the Twin Towers burning, he also received an eviction notice from his landlord. “I was ready to slash my wrists,” he says. Elaine, who was then working in Los Angeles, feared for his partner’s life. “I remember talking him down on the phone that day and the day after. He was definitely in bad shape, and I was wringing my hands and in tears talking with him.” Basinski and his neighbors and nearby friends spent the day on the rooftop in collective grief. The only thing that comforted the group was TDL cranked up on a pair of speakers, its beauty perpetually dissolving into dust. At least until “the girls downstairs freaked out and asked me to turn it off,” Basinski recalls. As the sun began to set, Basinski turned on a video camera and captured the last hour of light, the smoldering skyline sliding into darkness. Stills from the footage would later serve as the album’s cover art.

His friend Makoto Fujimura, a Japanese American artist and devout Christian who was displaced from his home near Ground Zero, provided a lifeline for the despondent Basinski, helping him out of his depression and giving him perspective. “I simply asked him, ‘How are you doing spiritually?’ and he broke down and wept, and I wept with him,” Fujimura says via email of the fraught days that followed. “He began to find an echo of a greater redemptive grace. He began to hear the ‘still small voice’ of God pointing him to eternal hope.”

In 2002 Basinski made CDs of TDL one by one and sent them to whoever he thought might listen. “On its first release, the connection between it and 9/11 was a little fuzzier,” remembers Mark Richardson, who reviewed the album for the music website Pitchfork. “I think it helped its cause immensely by being beautiful, drawing you in as a piece of ambient music that fills a room. That gives it an emotional pull that makes the source material’s slow disappearance all the more tragic.” As the nation grieved, Basinski’s music started to spread.

There were positive critical reviews and word-of-mouth recommendations, but something else lurked within TDL for listeners. Consider the relatively short and drastic track “dlp 4.” It starts with a pensive minor-key melody and a snare drum, like a somber march. It’s sad but hummable, yet with almost every pass of the loop, these elements flicker and dim, like a radio station that’s slowly falling out of range. Soon you’re in a blizzard of static with only a sliver of that original melody. Within twenty minutes, there’s nothing left but a lonely crackle.

Reddit threads and YouTube comments today show that listeners still connect with TDL. Memories of 9/11 appear, as do mentions of the loss of a loved one. Some hear grief and depression, isolation and end times, while others are filled with indefatigable triumph and a sense of hope. It’s mournful music that embodies the true nature of life and mortality. In his seemingly static loops, Basinski signals a deeper understanding about our world: decay is part of life, as is destruction.

“September 11 gave people a keyhole . . . a way to understand his music,” Elaine says. “It was catastrophic beyond imagination, not just physically but to our psyche. It affected everyone’s lives. That opened up possibilities for people to stop and listen.” And people did listen. Basinski constantly hears from creative types who use his music to concentrate. Others listen to process grief or to impart calm during childbirth.

Today Basinski is a revered figure in ambient and experimental music circles. His influence can be heard in the work of the popular Austin post-rock band Explosions in the Sky and celebrated composers such as Nils Frahm. The music he has recorded since TDL ranges from the submerged calm of 2003’s Watermusic II to 2019’s unsettling On Time Out of Time, built out of the sound of two black holes merging 1.3 billion years ago, as captured by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory.

Another recent project, created with his studio assistant Preston Wendel under the band name Sparkle Division, gives Basinski the chance to finally play the saxophone on his own records. Sparkle Division’s sound is a collage of sliced-and-diced blues, exotica, R&B, and noir jazz. Its funkiness and effervescence seem worlds away from the rest of Basinski’s music, though it isn’t entirely out of character for him; while most ambient artists are low-key and averse to attention, Basinski often performs decked out in glam attire worthy of Bowie.

Basinski doesn’t care what anyone else thinks about his contradictions. “It’s beautiful here in California, and that keeps me a little more balanced. But . . . I have a tendency towards melancholia.” He pauses to take in his sunny environment, then sums up where he’s coming from. “I was born with the blues, baby.”

San Antonio native Andy Beta visited Arcadia in the summer of 2003. He contributes to the New York Times and the Washington Post.

This article originally appeared in the September 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Things Fall Apart.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Music

- Richardson