I remember exactly where I was the first time I heard Willis Alan Ramsey’s self-titled debut album. It was released fifty years ago, on May 5, 1972, but I didn’t hear it until almost twenty years later. It was a Saturday afternoon in the spring of 1990, and a buddy of mine, a guy named Mike Lung, had decided to be a songwriter. The two of us went to the old vinyl annex of Austin’s Waterloo Records, where Lung hoped to find Guy Clark’s first two records, the albums that had inspired his dream. Waterloo had them, and Lung took them to the register, where he was checked out by none other than Alejandro Escovedo. Al was already a roots-rock legend and on his way to being named the “artist of the decade” by No Depression. So we were stunned to see he had a day job, and more than a little proud when he nodded approvingly at Lung’s picks. But then he let us in on what sounded like a rock star’s secret.

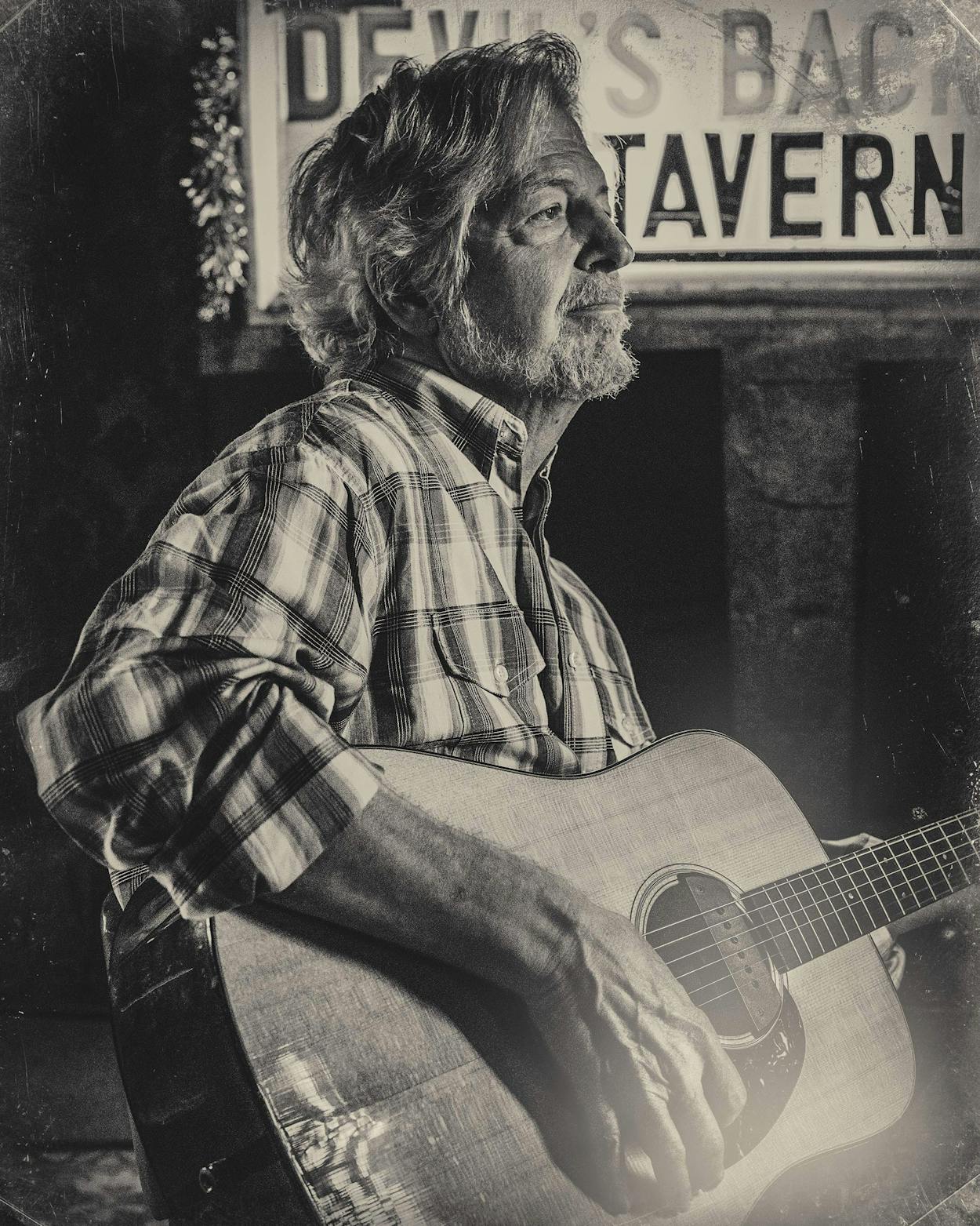

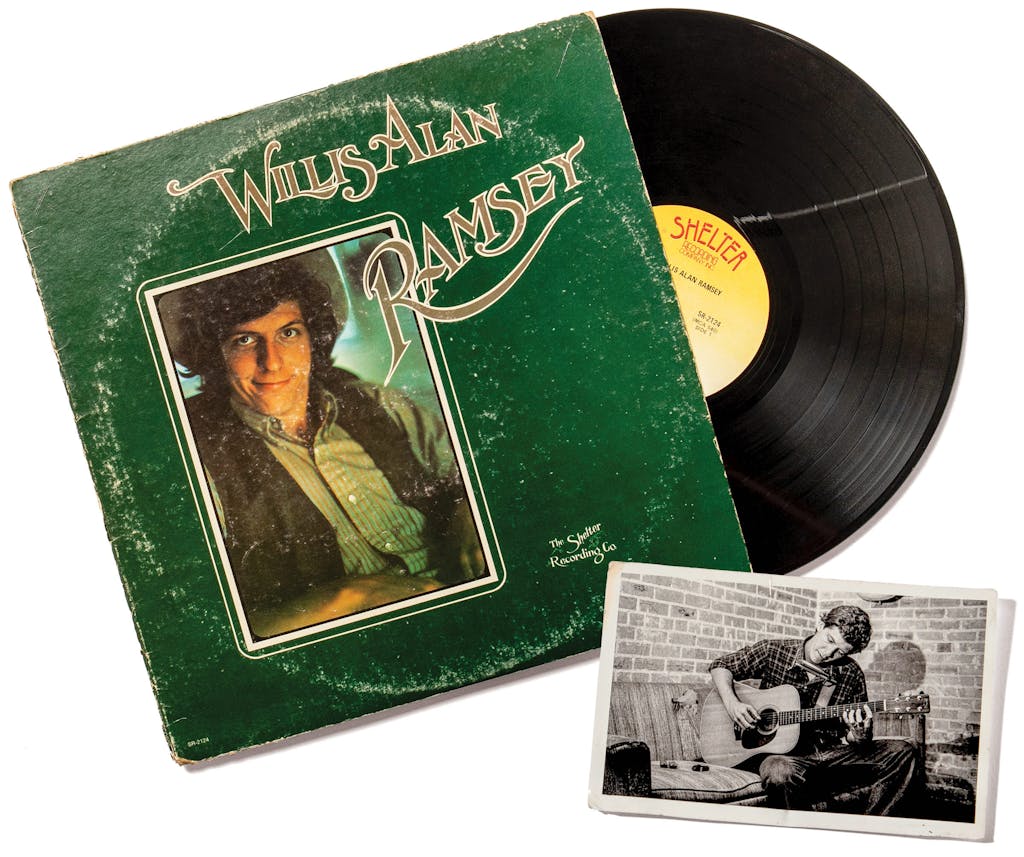

“So if you guys like Guy,” he said, “does that mean you like Willis?” We responded with dumb, blank stares. “Oh, man,” he said, turning around to the long rows of vinyl the clerks played in-store, finding the one he was looking for instantly, as if he’d just finished listening as we walked in. “Willis is a songwriter’s songwriter,” he explained as he pulled the platter from its sleeve. The album, he told us, had come out on Leon Russell’s label, Shelter Records. “It was the first great Austin record, before any of the cosmic cowboy cats.” He put it on the turntable and handed us the cover. It was dark green, with a photo of Willis kicked back in repose, with a cowboy hat crooked at an aw-shucks tilt atop his dirty blond hair and an insouciant, satisfied grin. “They were all chasing Willis,” he continued, as the music started to spin. “He’s a genius. You gotta know this record. It’s one of the best singer-songwriter albums ever made.”

As the first song, “Ballad of Spider John,” opened, Lung and I looked at each other with bugged eyes and dropped jaws, staying that way through the next two songs, “Muskrat Candlelight” and “Geraldine and the Honeybee.” We were familiar with the second number; Captain & Tennille had a monster hit with their cover, renamed “Muskrat Love,” in 1976, when Lung and I were kids. But Willis sounded nothing like the famed pop duo—or anything else we’d ever heard.

Generally speaking, his album featured the same elements favored by other Texas singer-songwriters we’d started listening to, specifically exquisite guitar picking and spare arrangements that left room for the words. But those artists were typically classified as country, and Willis sounded closer to blues—“Honeybee” was essentially fingerpicked ragtime. There was a playful, childlike quality to the songs, which were nominally about things like small animals, bugs, and watermelons, but Willis sang them in a voice that sounded somehow eternal. It all added up to a record that seemed to exist outside of time; the rich, warm sound aside, there was no way to tell if it was from the nineties, the seventies, the fifties, or before. Lung told Al he’d take it, and I remember feeling the same sensation I had the first time I visited the Grand Canyon: This has existed my whole life, and I’m just getting here?

But then Al let loose the other shoe that always drops when the topic is Willis. As Lung wrote out a check, he told Al he’d be back for more Willis after his next payday. “There is no more Willis,” Al told us. “He never did release another record. And that’s the crazy thing: Supposedly, he’s been working on the follow-up ever since. But he’s never finished it. We’re all just waiting.”

With that discovery, our new lives as Willis nerds were in full bloom. His album became a go-to, the thing I’d put on whenever I couldn’t decide what to put on. And I read everything about him I could find. I learned that Willis, then just nineteen years old, had gotten his record deal by showing up, uninvited, with his guitar to Russell’s room at Austin’s Villa Capri hotel and announcing that he’d written some songs Russell needed to hear. I learned that Willis then spent the year recording in five different studios, with a different set of backing musicians in each spot—and that they were some of the biggest sidemen in history, players such as bassists Carl Radle and Leland Sklar and drummer Jim Keltner. I learned that Willis had been one of Shelter’s big hopes, along with label mates such as J. J. Cale, Tom Petty, and Phoebe Snow. I also learned a little about Willis’s irascibility, like the way he declined to go on the tour Shelter booked to promote the record—but how it had found a constituency with the cool kids anyhow. For a while in the seventies, he was a big enough draw that roots-music lions such as Clifton Chenier, Mance Lipscomb, and Professor Longhair opened for him.

His story became more arresting with every detail, and his record never stopped mattering to me, my relationship to it changing as my life did. When I got married, eleven years ago, I learned that my wife Julie’s parents had been huge Willis fans when they were hippie kids at UT-Arlington in the seventies. I played the record whenever we got together, and we communed over their memories of seeing young Willis play at a Fort Worth pizza parlor called the HOP. When our second son, Leon, was born six years ago, his older brother, Willie Mo, who had just started talking, nicknamed him “Bee.” So I put “Geraldine and the Honeybee” on a playlist for Leon and told him the song was about him. When I play it for him now, he says he likes it because it’s “jazzy.”

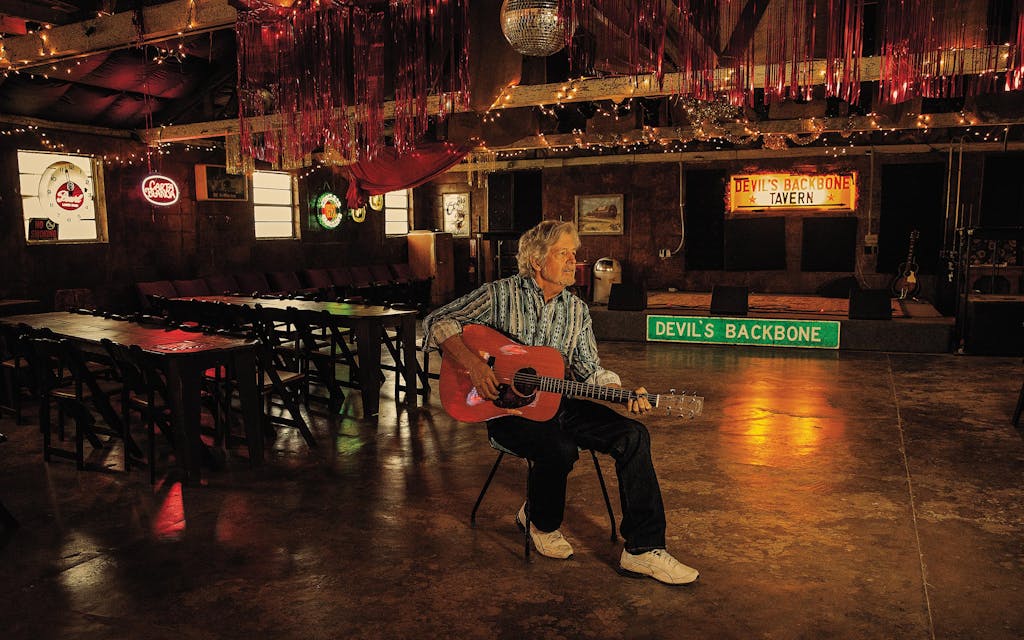

Last spring, Lyle Lovett hosted Willis on one of his pandemic guitar-pull livestreams. Julie and I made a night of it, grilling steaks and eating in front of my laptop. We were excited by the prospect of hearing Willis songs we didn’t know—because he never did put out that next album. He was charming that night, playing songs old and new, fully at ease with the idea that his second album will come once he decides it’s ready. At one point, Lyle praised a new tune and asked if it would be on the next record. Willis smiled and said he was thinking he’d hold it for the third. When Lyle asked Willis what he told fans clamoring for that fabled second album, Willis responded, as he often has, “What’s wrong with the first one?”

A great many of us, including these five artists who have covered his songs, can tell you the answer: absolutely nothing.

Jimmy Buffett on

“Ballad of Spider John”

Singer-songwriter, author, and entrepreneur Jimmy Buffett covered “Ballad of Spider John” for his third album, 1974’s Living and Dying in ¾ Time.

I first got noticed in the early seventies, after Jerry Jeff Walker made me come to Austin. I was already living in Key West but actually playing more in Texas, and Austin was just getting started. It was this amazing melting pot of great songwriters, from Jerry Jeff and Willie to Michael Martin Murphey and Steve Fromholz. Willis was one of those guys.

When I got his record, I loved everything on it. I didn’t know it at the time, but he’s originally from Alabama, and I’m from Mississippi. Being a big reader, I heard a little Flannery O’Connor and Mr. Faulkner in there. His catchy phrases and rhyme schemes were different, a little more literary than most of the Texas stuff. I listened to it a lot while working on A White Sport Coat and a Pink Crustacean [from 1973]. But White Sport Coat covered about 80 percent of my set list. So, when I went to follow it up, I needed something more.

That’s where “Spider John” came in. Because, not knowing much about Texas, I thought it painted a vivid picture—right up there with “Pancho and Lefty.” And everybody in the world already knew “Pancho and Lefty,” so I went for “Spider John.” It’s a wanderer’s tale, kind of like “El Paso,” by Marty Robbins. Willis sang, “I was a supermarket fool / I was a motor bank stool pigeon / Robbing my own time.” That was great. And then Spider John couldn’t confess his sins to the girl, Diamond Lil, because he knew if he did, “she would surely take her leave,” which of course she did anyway.

I kind of want to know where Diamond Lil is these days. And I still listen to that album. I haven’t put it on in a while, but hell, I’m 75. I’m working on long-term and short-term memory every day. And this might be my new “count backwards from one hundred by sevens” test: if I can wake up each day and name every song on Willis’s album, then I still have it.

Toni Tennille on

“Muskrat Candlelight”

In the fall of 1976, pop sensation Captain & Tennille—the Grammy-winning husband-and-wife team of Daryl Dragon and Toni Tennille—had a number four hit with their cover of “Muskrat Candlelight,” renamed “Muskrat Love” in 1973, when it was originally covered by the band America.

You know, I have never met Willis. Even when “Muskrat Love” was number one [on Billboard’s Easy Listening chart], I only talked to him briefly on the phone once, and that was it. So I don’t know what he had in mind when he wrote it. “Singing and jinging the jango”? Who knows what that is? I don’t. But I thought it was Disneyesque. They were dancing, “floating like the heavens above.” And the other thing that made me laugh was that Willis was one of the hip people, part of the in-crowd, while we were considered boring old pop. So I wondered if he had mixed feelings about what a huge hit it became. It ended up being the third-biggest single we ever had.

In 1974 or so, Daryl and I were in L.A., working clubs, trying to get a record deal, and we ended up at a “top-level” place called the Smoke House. We’d play from 9 p.m. until 1 a.m., mixing our versions of Top 40 hits with songs I’d written and songs Daryl chose that were more out there, like he was. And we built up a big following. People would be waiting in line to get in. We knew we had something.

One night, we were driving in, listening to the radio for songs to add to our set, and we heard one by America. The vocal was kind of buried; I couldn’t really hear the words. But I said, “Daryl, I think this is about muskrats in love.” So we went to buy the sheet music, and right there in the store I read the lyrics and laughed out loud. I said, “This is a hoot. Why don’t we try it in the club?”

So Daryl, in all his wonderful weirdness, decided he was going to have the muskrats sing. And he worked up the sound of muskrats on a synthesizer . . . that darling little dee dee dee part he put in there. The first time we tried it out—not sure at all what the reaction would be—people went nuts. They just loved it. “Play that again!” We actually had to cap it at twice a night.

By 1976, we’d had the big hit with “Love Will Keep Us Together,” and we were invited by President and Mrs. Ford to perform at the White House. It was a bicentennial celebration—a very big deal. Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip were going to be there, and Henry Kissinger and his wife, the president and Mrs. Ford, all in the front row.

We wondered what to play. We were only doing five songs, but we were so new that we didn’t have many things people knew. “Muskrat Love” hadn’t even been released yet. And the only other hit we’d had was “The Way I Want to Touch You,” which was going to be a bit risqué for this crowd.

During sound check, Mrs. Ford came in to introduce herself, and she asked if we were going to play “The Way I Want to Touch You.” When I told her no, she said, “Oh, but you must! It’s Jerry’s and my favorite song.” I thought, “Oh, my God.”

After sound check, I told Daryl we were putting it back in. I said, “Look, this is a pretty hip White House . . . so why don’t we also do ‘Muskrat Love’?” It had been so popular in the club, and I thought these people would get a kick out of it. So we played it in the White House.

We never were invited back, ever. And we actually got some bad press from it. I remember Julia Child, who was in the audience, calling it [feigns a haughty English accent] “a song of sexual innuendo inappropriate for royalty.”

Still, when we released it as a single, it went bananas. So I guess it’s polarizing; some people love it, and others just hate it. All I ever thought was that it was a sweet song about these charming little characters, like a Mickey Mouse thing. That’s what I saw when I sang it, and it always made me smile.

Shawn Colvin on

“Satin Sheets”

Austin singer-songwriter Shawn Colvin, a three-time Grammy winner, covered “Satin Sheets”—along with songs by Bob Dylan, Sting, Tom Waits, and Jimmy Webb—on her 1994 album Cover Girl.

In 1976 I had fallen in love with a fiddle player in Illinois, joined his band, and then we moved to Austin. Willis’s record was already four years old, and I hadn’t heard of it. But we stayed with a friend of my boyfriend’s who had it. And in Austin, this was the record you listened to. Somebody put it on the turntable, and I fell in love.

In the early eighties, “Spider John” was a big mainstay of my set when I’d play places like the Bitter End, in New York. But when I recorded my covers album, I wanted something a little more obscure. So I went with “Satin Sheets.” It’s got an open-G tuning, which was one of its tricks. It’s such a cool song to play on the guitar. And I absolutely loved the lyrics. He mentions a calliope! And I love singing lines like “I tell you, boys / I’d buy a new Rolls-Royce” and “Hallelujah, what’s it to ya?” and “Boogie-woogie ’cross the silver screen.” It’s just so tongue-in-cheek, or maybe “sarcastic” is a better word. I feel like he was kind of taking the piss out of stardom, kind of a “rock star, schmock star” thing.

I still put that album on all the time. I listened to it a lot last year in particular. I go to Montana twice a year with my brother, who is eight years younger than me. Last time, I hooked up my phone to the rental car and said, “Listen to this.” Because he hadn’t heard Willis before. We listened to it over and over again, the whole trip.

Jimmie Dale Gilmore on

“Goodbye Old Missoula”

Together with Joe Ely and Butch Hancock, singer-songwriter Jimmie Dale Gilmore was a member of Lubbock’s legendary Flatlanders, a short-lived early-seventies country act that was hailed as an Americana supergroup when they re-formed in 1998. Gilmore covered “Goodbye Old Missoula” on his 2000 solo album One Endless Night.

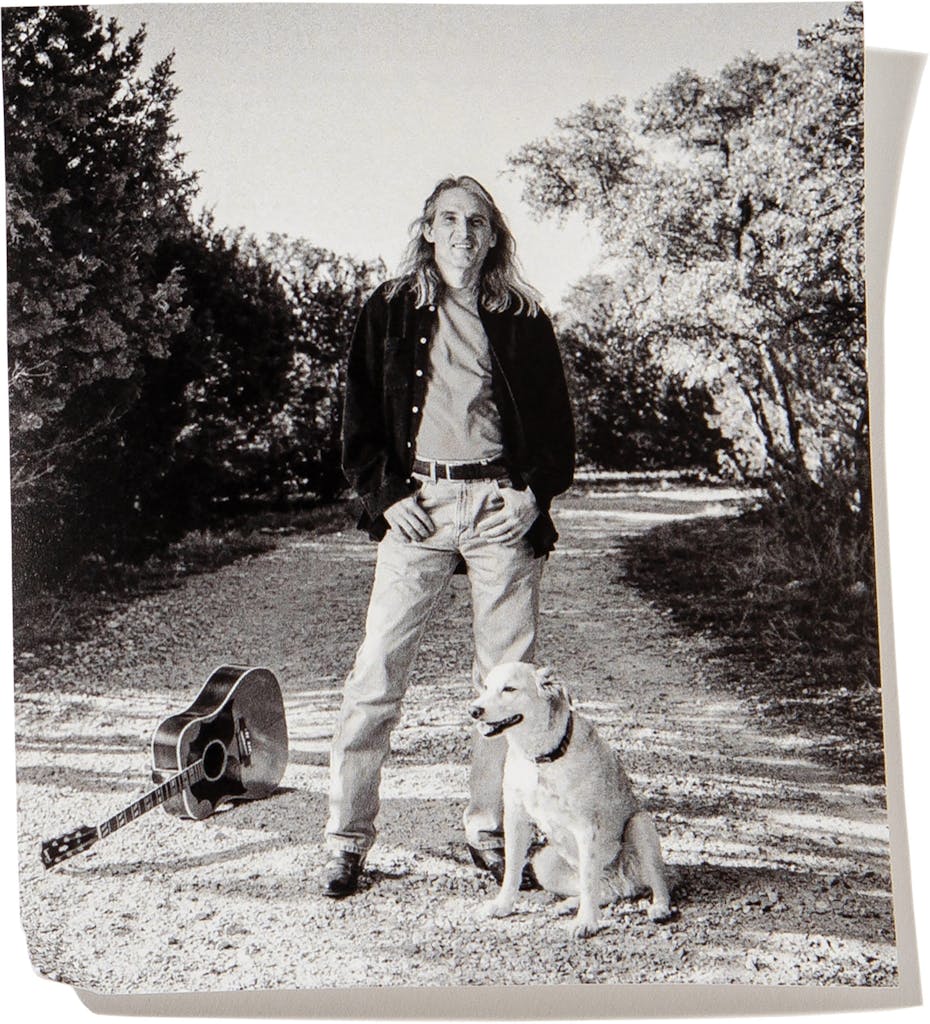

I first met Willis when he was living in Nashville in the nineties. He was already this giant legend, and we hung out a bit and got to be pretty good friends. We talked a lot about music, and there was an idea that we might try to make some. But that never happened, and I never pushed it.

In the early days of the Flatlanders, in our real germinative period—which was one of the most significant and prolific times for all three of us—we lived in the same house together. And Willis’s album was one of the ones we had on nearly every day. Because we had a turntable and a big stack of favorite records. We were all three Dylan and Townes fans, plus everything from Lightnin’ Hopkins to the Stones and Beatles . . . and Willis. As far as I know, we were the only ones in Lubbock listening to him. I don’t remember him getting any radio play at the time; this was well before Captain & Tennille and everybody started covering him.

There was a depth in his voice, which was strange, with him being so young. It really brought up the question of where this came from. And I loved that you couldn’t pigeonhole it. You couldn’t say it was country or folk, though those elements are there. And it also had a pop feel, which I always attributed to [his mentor] Leon Russell being such a broad-ranging musician. It always felt to me like they treated each song as its own little work of art. I loved everything on it.

But there was something about “Goodbye Old Missoula” in particular that grabbed me. It sounded like it could have been an ancient folk song. Just the words “goodbye to old Missoula” sounded archetypal somehow. But I loved every line. Right from the song’s start, it’s cold and lonely. “Searching for the sunlight on this winter’s day . . . But they’ve thrown the sun away.” And then he sings, “I’m headed for the Bozeman round.” He didn’t need to explain that. I thought, “Okay, that makes sense: he has to leave and doesn’t want to.”

I never knew if he was talking about a real relationship with an actual woman. But that song was so alive with feeling that it seemed he was. There was a universality to it, like the line “Goodbye Rosie, you’ll never know.” That one little phrase contains a novel.

Lyle Lovett on

“Northeast Texas Women”

Four-time Grammy-winning singer-songwriter Lyle Lovett splits his time between Austin and Klein, Texas. He has performed various songs off Willis Alan Ramsey in his live shows ever since discovering the album.

My first musical partner in crime was a high school buddy named Bruce Lyon. He was a year older than me, and he went to [UT] after graduating [in 1974], so I’d drive to Austin to knock around, to go hear music and practice our songs. Bruce was a conduit to me. He would tell me about the artists we’d hear on KOKE-FM, which was huge on playing Texas music: Guy, Jerry Jeff, Murphey, Rusty Wier, Willis, all those guys. I read Jan Reid’s The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock from cover to cover at least twice that year because they were all in it.

So I went looking for Willis’s record—the “green album,” as he refers to it—and found it near campus, at Inner Sanctum Records. I think I paid $4.99 for it. It was an absolute revelation. He had such a keen sense of humanity, of pain and loss and joy and hope—everything that makes us human. And a wonderfully poetic way of expressing it. I was immediately drawn in. In fact, I bought Buffett’s Living and Dying in ¾ Time because he’d recorded “Spider John.” That’s how much I loved Willis’s album.

Not long afterwards, Bruce took me to see Willis for the first time at the Paramount. We sat in the balcony, and I remember loving how “un-performing” his performance was. When he stood there and played, he seemed almost uncomfortable, which I related to in spades. Because I was terribly uncomfortable with the idea of performing. He gave me hope that you didn’t have to dance across the stage with your hands in the air and say, “Hello, Austin! How are y’all doing tonight?” It told me it was okay to have your own sensibility.

Plus, he wore a pair of Adidas, nylon SL72s. Those were the same shoes I wore. I thought, “I love this guy right down to his shoes.”

I went on to play almost every song off his record in my shows. I never got to “Watermelon Man” because it has that slide guitar on it, and I can’t do that. And I’ve never played “Angel Eyes” because I still haven’t figured out its tuning. But I’ve played the rest.

One, of course, is “Northeast Texas Women.” The lyrics are so specific, about a specific subject matter and place. “Cast-iron curls . . . aluminum dimples . . . and cotton-candy hair”? It just nails that Dallas look. Years later, he told me he’d mentioned Old Dime Box because he’d seen a sign for that town when he was on the coffeehouse circuit, driving from A&M to Austin. I loved that because I’d made that drive and knew that sign. But I also just loved the words. Willis writes words that sound good together, that have round edges and roll off your tongue and sing pretty, so even if you didn’t know Old Dime Box actually existed, it wouldn’t matter. It just sounded cool.

But also, that song is a great lesson in how you can write about something specific and have it translate to the universal. And the universal is about any woman anywhere, and that whimsical bewilderment in the male-female conundrum. And he delivers it with a side-eye, raised-eyebrow playfulness, which is Willis’s nod to a greater insight. Playfulness is how you cope with pain. They go hand in hand.

I’ve gotten to know him over the years, and he’s become a dear friend. But he’s still a mystery to me. I believe he hears things I just can’t. He’s played me his unreleased recordings, and they are absolutely release-worthy. But I always tell people, if you appreciate Willis’s result, you have to respect his process. And if he never puts out any of it, that’s enough. He’s like the Harper Lee or J. D. Salinger of music; that record is required listening in the same way that To Kill a Mockingbird is required reading.

But I remember the first time I ever really talked to him. In 1979 he played a coffeehouse in College Station called the Basement, and I opened for him. I was also a journalism student at A&M, and I interviewed him for the Battalion, so I brought my copy of The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock and asked him to sign his chapter when we met before the show. But I did not linger. I was a serious journalist. Everyone wanted to know about the second album, so I asked a one-word question: “When?” He gave me a very succinct, definite answer.

He said, “Soon.”

Jimmy Buffett on

The Fabled Next Record

There’s been a lot of tears and frustration with why there’s not been another album. Everybody’s been waiting for fifty years. But I’ve got an idea.

I’m always looking for cool guitars, and when I go to Los Angeles, I check in at Westwood Music. One day a couple years ago I was in there, and I was looking up on the wall and saw this old Martin D-18. I said, “What’s that?” And the manager, Mark Bookin, said, “Well, Willis Alan Ramsey is trying to finish his second album.” I guess he’d decided to sell some guitars to get some money to get that done. So I bought it. Because I didn’t want anybody else to even know what it was.

It’s sitting next to my ’52 Martin in my studio up in New York, and I love playing it. But I’ve decided I should give it back to Willis. Not sell it to him—I want to give it to him. So if he wants his guitar back, maybe we can make a deal.

I’ll trade him this guitar if he’ll put his record out. Because I’ve got a record label, and I’ll put it out tomorrow. I wouldn’t even have to listen to it; we’ll just do whatever he wants. We don’t steal, and we don’t cheat. He’ll get paid direct from Mailboat Records. Let me throw that on the table.

These quotes have been edited for clarity and length.

This article originally appeared in the June 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “You Never Forget Your First.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Music

- Shawn Colvin

- Lyle Lovett

- Austin