This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

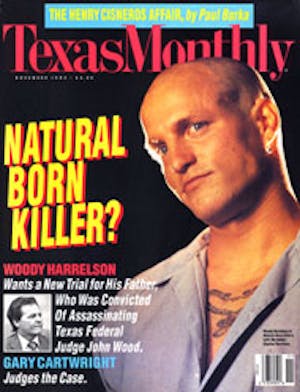

In late spring of 1979—around the time federal judge John Wood was assassinated outside his San Antonio townhouse—a handsome young man with blond hair, an engaging smile, and a vaguely familiar face confronted Yvonne Streit in the hallway of Houston’s Briarwood School. “Don’t you remember me?” the young man asked. “It’s Tracy.” Woodrow Tracy Harrelson! Streit, who ran the school for children with behavioral problems, couldn’t believe her eyes. Though Tracy had been one of her favorite students, she hadn’t seen him since 1971, when the then-ten-year-old transferred from Briarwood to another school. A few years after that, he and his mother and two brothers had moved to Lebanon, Ohio. Now the boy Streit knew as Tracy was called Woody. He had graduated from high school and received a scholarship to Hanover, a small college in Indiana. He had planned to study drama or journalism, she recalls, because “he had a story that he had to tell.”

Streit knew a little about the story, though she didn’t know that it was about to take a maniacal twist—that the plot would ultimately turn on Judge Wood’s murder, or that it would involve Tracy’s father, Charles Voyd Harrelson, a card player and hustler who had served time in prison before Tracy was born. In 1968 Harrelson had deserted his family. The next they heard of him, he had been charged with the for-hire murder of Alan Berg, a wealthy Houston gambler. Tracy heard the news on the radio. When he asked his mother if the killer was his father, she refused to say. “How many Charles V. Harrelsons can there be?” he asked himself. “That has to be my father.”

That fall, when Tracy enrolled at Briarwood, he was “like a trapped animal,” Streit says. “If things didn’t go his way, he reacted with anger, kicking wastebaskets, that sort of thing. Once he stabbed me in the leg with a stick. He was trying to ask for help, but he didn’t know how.” After three years, she says, the boy was calmer, more self-assured. She heard later that some of her work had been undone, that people in the neighborhood had taunted him about his father’s criminal record and provoked new outbursts. That was why Diane Harrelson took her sons to Ohio. Streit had observed that kids like Tracy often learn to channel their energy in creative ways and become famous artists—so she wasn’t surprised in 1985 to find her pupil playing Woody Boyd, the lovable boob of a bartender on the hit TV show Cheers. By that time Charles Harrelson had been convicted of murdering Judge Wood and was serving two life sentences. Then Tracy telephoned Streit offering money for a scholarship. “I want it to go to some kid like me,” he said. “There’s not another kid like you, Tracy,” she replied.

Streit hasn’t seen Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, in which Woody gives an unforgettable performance as Mickey Knox, a charming rogue who, with his equally blood-crazed young wife, travels the country and brutally kills more than fifty people. Streit suspects that this is the story he had to tell. But now that the movie is out, things have gotten complicated. Woody is telling interviewers that he grew up brawling and carousing—behavior that people in Ohio don’t remember. In a bizarre case of life imitating art, he now claims that his own persona is much closer to that of Mickey Knox than that of Woody Boyd. “I think there’s many times that if I’d been holding a weapon, I’d have killed somebody,” he told Details magazine writer Rob Tannenbaum.

More important, Woody has renewed his calls for a new trial for his father, who corresponds with him from a federal prison in Atlanta. “I’m not saying that he did or didn’t kill the judge,” Woody has said. “I’m just saying he didn’t get a fair trial.” In Natural Born Killers, Mickey Knox observes that “you can’t get rid of your shadow.” Woody Harrelson’s shadow is a father he never knew.

Woody was a junior at Hanover College when Charles Harrelson reappeared in his life, by way of a letter written from jail. This sudden expression of fatherhood shook the very foundations of the son. In Lebanon Woody had lived a model life—playing sports, acting in plays, generally making things lively and pleasant for those around him. “He was pretty much like the character he played on Cheers—friendly, outgoing, good-hearted, but a little on the goofy side,” says Wayne Dunn, one of his drama teachers at Lebanon High. If he ever got into a fight, Dunn never heard about it. Woody attended Sunday school regularly, and a church youth group met at his home. His church arranged the scholarship to Hanover, and at one time he thought about studying theology. But after the jolt of discovering his father, Woody seemed to change almost overnight. He turned rebellious. He gave up religion and started drinking and fighting. The antisocial behavior came back with a vengeance.

Woody came face to face with Charles in 1982, the summer after the first letter. “He came down here numerous times,” says San Antonio attorney Alan Brown, who represented Charles immediately after he was indicted for the murder of Judge Wood. “He wasn’t a star back then—just a strange kid who didn’t say much.” Only father and son know what they talked about, but in that period Woody changed from a sweet kid into a head case, if not a menace to society. He had been won over by his father’s charisma. “This might sound odd to say about a convicted felon,” he later said, “but my father is one of the most articulate, well-read, and charming people I’ve ever known.”

Woody Harrelson wasn’t the first to be dazzled by Charles Harrelson’s seamless line. Charlie was without question a charmer—handsome, self-confident, and surprisingly polished, though he had barely finished high school. Obsessively neat, he had a taste for expensive clothes and cars and the finest Scotch whisky and wine. Though he acknowledged a burning desire to be rich, he left the impression that making money was the easiest thing in the world. “You could drop me off broke and buck naked in the middle of downtown Houston,” he told me once, “and in six months I’d be wearing custom-made suits and driving a Cadillac.” He bragged that he had never held an honest job, which was a lie: He had once sold encyclopedias. During many months of solitary confinement he learned to handle cards the way a surgeon handles a scalpel; he was what gamblers call a card mechanic. Yet despite his obvious talents, he made most of his money cheating other gamblers. Charles Harrelson’s only rule of life seemed to be: Break all the rules.

His greatest talent was his ability to manipulate people, especially women. There was something almost old-fashioned in the way he treated them, hurrying to light cigarettes or open doors. Women adored him and would go to ridiculous extremes to do his bidding. Diane Harrelson married Charles almost on impulse while he was in Houston on leave from the Navy. Like others before and after, she stood by him when he served a prison term in California in 1960 for theft. In 1968 another woman, Sandra Sue Attaway, admitted to police that she had lured Alan Berg out of a Houston nightclub and into Harrelson’s red Cadillac for what turned out to be Berg’s last ride. Even behind bars, Harrelson had a way with women. When he walked out of the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1978, there was a rented limousine waiting for him, a gift from a young woman he had met while he was on trial for Berg’s murder. A short time later, Harrelson married another woman, Jo Ann Starr, and prevailed on her to buy the rifle he used to kill Judge Wood—even while carrying on affairs with Starr’s daughter, with his best friend’s wife, and with El Paso heiress Virginia Farah. He was driving Farah’s Corvette and mainlining cocaine in September 1980 when police arrested him, after a six-hour standoff on a highway outside of Van Horn, on drug and weapons charges.

And yet, for all his self-promotion, Charles Harrelson was basically a punk. Except for the Wood hit, he made a total of $4,000 as a killer—$1,500 for doing Berg, and $2,500 for the 1968 contract murder of South Texas grain dealer Sam Degelia, Jr. After firing several shots into Degelia’s head, Charlie bragged to a companion, “This is not the first son of a bitch I had to ring the bell on and won’t be the last.” But Harrelson was soon sent to prison, and more than a decade went by before he killed again. After his release in 1978, he collected debts and hustled card games at country clubs, posing as a wealthy doctor or rancher and setting up marks for other gamblers. His take was usually 25 percent of his employer’s winnings. Woody has told journalists that his dad was so good at cards that he was banned by several casinos in Las Vegas, a contention so ludicrous that even Woody Boyd would have trouble buying it.

Not long after Charlie was charged with Wood’s murder, I interviewed him in the Bexar County jail for Dirty Dealing, my book about El Paso’s notorious Chagra crime family. By previous arrangement with attorney Alan Brown, I avoided questions about the judge. We talked instead about his background and about books. Charlie told me he was reading mysteries by Elmore Leonard, who he said had a good ear for the vernacular of the underworld. That’s the word he used—“vernacular.” He talked about growing up in the shadow of the Texas prison system, on his daddy’s 82-acre farm in Lovelady near the Department of Corrections’ Eastham Unit. He painted a picture of a bleak small-town life: For entertainment, he used to practice cheating at cards in front of a mirror. Later, he lived in Huntsville, where his uncle was a warden at the state’s main prison unit. The criminal mind-set came to him naturally, but it didn’t explain why he chose a life of crime: One of his brothers became an FBI agent and another a polygraph expert. In fact, Harrelson loved his image as a killer. When he recalled his stint in Leavenworth he affected a sort of swagger, as though he were telling me about the time he captained the polo team at Princeton. He led people to believe that he did time there for murdering Degelia, even though his sentence actually resulted from an old gun possession charge.

Percy Foreman, who defended Harrelson in the Berg and Degelia cases, once observed that he had never seen Charles as content as when he was in Leavenworth. “He probably had more respect there than anywhere he’s ever been,” Foreman said. “The hired killer has a certain aura about him.” On several occasions, just to make himself sound important, Harrelson confessed to crimes he hadn’t committed. During the standoff near Van Horn, he confessed to the murders of both Judge Wood (which he later retracted) and John F. Kennedy. That day at the Bexar County jail, I asked Harrelson if he was sticking to his story about the JFK hit. “Yeah, I did the man,” he said with a tight grin. I knew he was jerking me around, but it didn’t matter. Under other circumstances, this was a guy I might have enjoyed knowing, if only for the perverse pleasure of witnessing what he did next.

Harrelson’s connection to the JFK assassination stems from the famous photograph of the “three tramps,” who were arrested near Dealey Plaza a few minutes after the shooting but were released before anyone thought to get their names. The tall tramp looked very much like Charles Harrelson, a coincidence Harrelson has exploited. While Oliver Stone was researching the movie JFK, he tried to interview Charlie in prison, but Charlie turned him down, which only made Stone suspect that he really did have something to hide. San Antonio attorney Tom Sharpe, who assisted Foreman during Harrelson’s first two murder trials—and later defended Harrelson in the Judge Wood case—was also struck by the resemblance of Harrelson and the tramp. But Sharpe compared the photo of the tramp taken in Dallas with one of Harrelson taken at about the same time and concluded it wasn’t the same person.

Whatever the truth, Charles Harrelson became a part of American folklore when he cut down John Wood, the only federal judge assassinated in modern times. He was paid a quarter of a million dollars for the hit by El Paso drug tycoon Jimmy Chagra, who was about to go on trial in Wood’s court and feared that “Maximum John” would send him away for life. Considering that the target was a federal judge, $250,000 seems a pitifully small amount. Though it was pocket change to Chagra, who sometimes lost $100,000 on a single roll of the dice, to Charlie it represented a hundredfold increase in pay. But Charles Harrelson didn’t do it for the money; he did it for the notoriety.

The contract was made almost by accident. Jimmy Chagra was famous for shooting off his mouth—only this time he shot it off in front of the wrong person. Attorney Tom Sharpe is reminded of the scene in the play Becket when the distraught king raves: “Will no one rid me of . . . a priest who jeers at me and does me injury?” Soon after, four hoods are slashing Becket to ribbons. That’s the way it was with Wood, except that Harrelson did the job alone. Chagra didn’t realize he had taken the offer seriously until he heard Wood was dead.

Several months later, Harrelson described the hit to Jimmy’s brother, Joe Chagra, an attorney who was representing both him and Jimmy. Harrelson told Joe he had been stalking the judge for weeks and had almost killed him outside the federal courthouse in Midland the previous week. On the morning of May 29, 1979, the day Jimmy was to go on trial, Harrelson hid behind a carport and watched the judge walk to his car. Fixing Wood’s back in the cross hairs, he squeezed off a single round from a high-velocity .243-caliber hunting rifle. The bullet slammed into the judge’s back and shattered into dozens of fragments. “I watched him quiver for a fraction of a second, then twist and drop in his tracks,” Harrelson said. “I knew it had been a clean, perfect shot.”

Joe became the government’s key witness against Harrelson. Because of attorney-client privilege, this was a tricky legal maneuver. Joe was the only person who could connect Jimmy to Harrelson. He was caught in the middle of a plot that had been hatched without his knowledge. But the government had him in a bind: He faced several drug charges that could be stacked to send him away for years, or he could say he was part of the conspiracy to kill the judge and get a lesser sentence. That’s what he chose to do, fabricating two conversations in which he supposedly urged Jimmy to order the hit. I don’t believe these conversations ever took place, and I think the prosecutors knew it. They looked the other way while Judge William Sessions accepted Joe’s plea bargain and ruled that his testimony could be allowed under the crime-fraud exception to attorney-client privilege.

Sessions, who was a friend of Judge Wood’s and later served as director of the FBI, may have blown it. In the wake of the publicity generated by Natural Born Killers, Sharpe plans to file a writ requesting a new trial for Charles Harrelson. The writ will be based on the fact that Joe Chagra now admits that he lied about being part of the conspiracy and on Sharpe’s belief that Sessions was wrong to waive the attorney-client privilege. “I asked Joe on the witness stand, ‘When did you stop being Mr. Harrelson’s attorney?’ ” Sharpe recalls. “He didn’t have an answer.”

Even with these revelations, it’s doubtful that Sharpe will be able to get a new trial. But the remote possibility that Charles Harrelson may again walk among us gives an eerie resonance to Natural Born Killers, which ends with the two monsters out of jail and living happily ever after.

Oliver Stone’s decision to cast Woody Harrelson in Natural Born Killers was both brilliant and cynical—and not just because the movie has received a ton of publicity that it wouldn’t have otherwise. It allowed him to throw out the original screenplay and wing it. As Woody prepared to play a scene, Stone would tell him, “Just think of your dad.” Woody has always had a striking resemblance to Charlie, but in his portrayal of Mickey Knox the resemblance is scary. He affects not only the mannerisms—the tilt of the head, the sardonic twist of the mouth—but he somehow captures the essence of controlled violence that made Charles Harrelson much more than just another mad-dog killer. “When Woody looks at the camera and says, ‘You ain’t seen nothing yet,’ you hear Charlie speaking,” Tom Sharpe told me. In one scene, Mickey corrects an interviewer who refers to him as a serial killer. “Technically,” he says, “[I’m a] mass murderer.”

Stone plays with the notion that the capacity to kill is genetic, a theme repeated in many recent stories about Woody. “I come from violence,” Woody/Mickey says in the movie. “It’s in my blood. My dad had it. It’s my fate.” But Charles Harrelson didn’t kill because he couldn’t help himself; he killed for money and fame. He didn’t kill because there was something added to his makeup, but because there was something missing—a conscience. Harrelson used to say that he regarded the human head as nothing more than “a watermelon with hair on it.” After he killed Judge Wood, he wrote that he felt sorry for his victims’ loved ones, then added: “But I’ve never killed a person who was undeserving of it.” As Mickey Knox, Woody uses almost those exact words. “Some people deserve to be killed,” he says.

Maybe it’s growing pains, but Woody’s identity crisis seems even more acute since he finished Natural Born Killers. He has even begun blaming his alienation on his mother, Diane Harrelson, who never remarried. She is by all accounts a decent and deeply religious woman who managed to raise three sons on her salary as a legal secretary. It must pain her to read how she failed Woody, or to learn what a bruiser her boy turned out to be. Others are equally puzzled. “Maybe this is a side of Woody we never saw,” says Wayne Dunn, his mentor at Lebanon High. Rob Tannenbaum, who spent several weeks with Woody while researching his story for Details, doubts that the tough-guy talk is a pose. “A friend of his told me that Woody beat the crap out of three guys who insulted him in a bar,” Tannenbaum says. “I think he’s constantly wrestling with these two personas, Woody Boyd and Mickey Knox. He wishes he could be closer to the former, but he keeps fighting the temptation to be the latter.”

Or maybe the revisionism isn’t that complicated: Maybe it’s Woody’s way of confronting a painful memory. Like Mickey says in Natural Born Killers, we all have demons inside us. It’s a matter of how we deal with them.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Woody Harrelson

- San Antonio