IN 1980 I ATTENDED MY FIRST RAP SHOWS IN THE South Bronx. Rap was new then, strictly the angry, energetic music of black New York teenagers. Only a couple of rap singles were on the market, pressed on twelve-inch vinyl and distributed by tiny independent labels; Kurtis Blow was poised to release the first rap album on a major label. If someone had told me then that in a decade the biggest rap star in America would be a white Dallas suburbanite, I probably would have eaten my subway tokens.

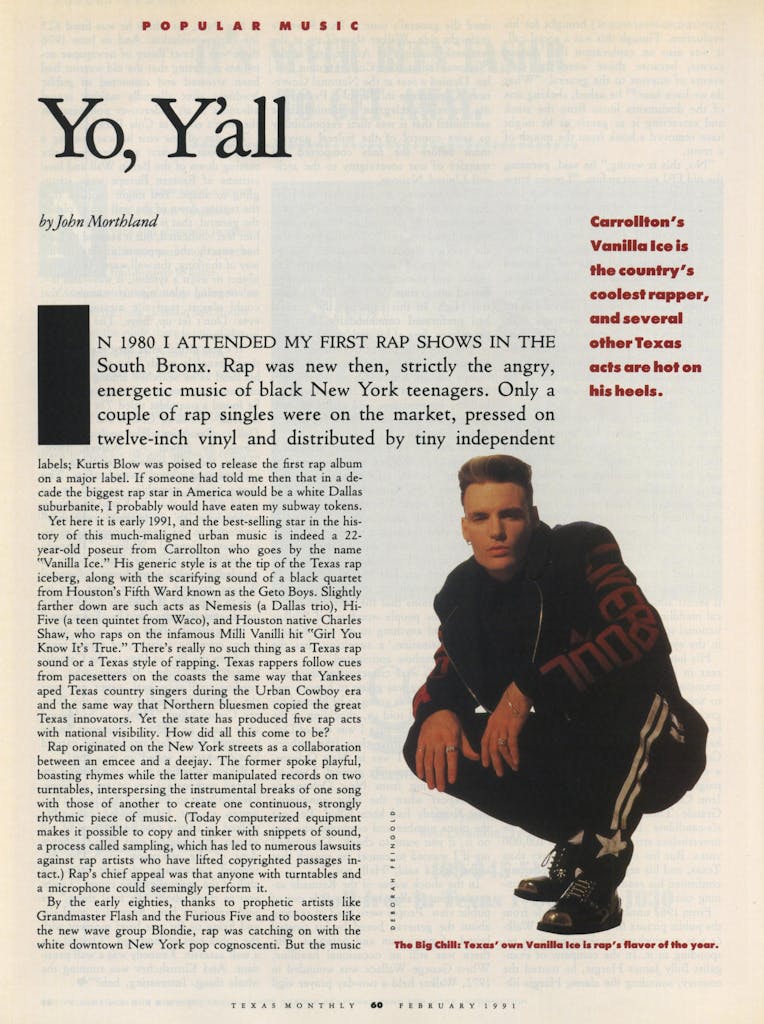

Yet here it is early 1991, and the best-selling star in the history of this much-maligned urban music is indeed a 22-year-old poseur from Carrollton who goes by the name “Vanilla Ice.” His generic style is at the tip of the Texas rap iceberg, along with the scarifying sound of a black quartet from Houston’s Fifth Ward known as the Geto Boys. Slightly farther down are such acts as Nemesis (a Dallas trio), Hi-Five (a teen quintet from Waco), and Houston native Charles Shaw, who raps on the infamous Milli Vanilli hit “Girl You Know It’s True.” There’s really no such thing as a Texas rap sound or a Texas style of rapping. Texas rappers follow cues from pacesetters on the coasts the same way that Yankees aped Texas country singers during the Urban Cowboy era and the same way that Northern bluesmen copied the great Texas innovators. Yet the state has produced five rap acts with national visibility. How did all this come to be?

Rap originated on the New York streets as a collaboration between an emcee and a deejay. The former spoke playful, boasting rhymes while the latter manipulated records on two turntables, interspersing the instrumental breaks of one song with those of another to create one continuous, strongly rhythmic piece of music. (Today computerized equipment makes it possible to copy and tinker with snippets of sound, a process called sampling, which has led to numerous lawsuits against rap artists who have lifted copyrighted passages intact.) Rap’s chief appeal was that anyone with turntables and a microphone could seemingly perform it.

By the early eighties, thanks to prophetic artists like Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five and to boosters like the new wave group Blondie, rap was catching on with the white downtown New York pop cognoscenti. But the music didn’t begin crossing over to the white charts until around 1987, when it won the imprimatur of MTV with the program Yo! MTV Raps. Since then, rap has been the most vital, urgent, and controversial music in an increasingly stagnant industry.

In New York the beat remained taut, crisp, and brittle, with just a hint of swing. Rap developed a fat, fast bass sound in Miami and had a poppish, orchestrated style in Los Angeles studios; a slow, menacing “gangsta” sound grew up in the nearby Compton ghetto. Rap themes also expanded and the music grew more factionalized. Some groups represented the militant, black-nationalist impulse; others encouraged politics of self-determination that were less racially divisive. The most notorious rappers, 2 Live Crew, went the carnal route, promulgating lyrics so sexually explicit and sadistic that obscenity charges were filed against the group in Florida and against clerks who sold the album in cities around the country, including San Antonio and Dallas. Much of 2 Live Crew’s approach, however, focused on party music and harmless braggadocio, which is the main thrust of rap in general. That less-threatening approach, combined with an insistent, infectious beat, ultimately allowed rap to enter the showbiz mainstream via acts like M. C. Hammer, a flashy dancer and limpid rapper.

Though rap still requires supple, slippery vocalizing, the success of Vanilla Ice seems to prove that anyone can do it. Late in 1990, Ice replaced Hammer at the top of the pop charts, becoming the first rapper to have a number-one single. His To the Extreme album (Ultrax/SBK), which sold five million copies in twelve weeks, became the first LP ever to go from gold to quadruple platinum in one month. As rap’s first white superstar, Ice has generated more controversy than Milli Vanilli, who lost a Grammy after admitting that they didn’t sing on their own record.

The Vanilla Ice brouhaha arose over another form of deception. His raps—and his interviews—are packed with harrowing tales of growing up in the ghettos of Miami, of attending the same school as 2 Live Crew’s Luther Campbell, and of sustaining knife injuries in gang fights; Ice has also claimed to be a champion motocross racer. But as Dallas reporters discovered, this macho man is in fact one Robby Van Winkle, who learned much of his posturing as a Pep Buster at R. L. Turner High School on the mean streets of suburban Carrollton. Ice has been modifying his bio ever since, allowing as to how he had grown up in Miami and Dallas. And maybe he wasn’t really a championship racer, though he did win some trophies. He also says that even though he went to a white high school, he did hang out in black South Dallas.

On one level, that is good old pop self-mythologizing of the kind that has been around since the early sixties. But one of the rules of pop is that when you make stories up, you must also back them up with your music. In Ice’s case, the invention is looking pretty thin. His phrasing, for example, is a faceless pastiche of various clipped New York deliveries. His hit “Ice Ice Baby” sampled so heavily from “Under Pressure,” by Queen and David Bowie, that Ice eventually added their names to the songwriting credits. When members of the national black fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha charged that Ice had mimicked its signature chant for the hook to “Ice Ice Baby,” he said that he had never heard of the organization—a statement that baldly ignored his original bio, which quoted him as saying the phrase was “a chant that’s done by the Alpha fraternity.”

If Vanilla Ice’s tepid, fuzzy, aural Xeroxes represent the innocuous end of the national rap spectrum, Houston’s Geto Boys embrace the violent extreme. Fronted by three emcees, including a dwarf known as Bushwick Bill, the Boys brag of being fouler than 2 Live Crew—in the name of exposing ghetto conditions. “Mind of a Lunatic,” on their Geto Boys LP (Def American Recordings), was ostensibly inspired by the murderous exploits of Charles Manson, and it fantasizes about slitting a woman’s throat and having sex with her corpse. But the Geto Boys’ approach is so one-dimensional that they seem to be, or at least to accept, what they rap about. Their music, meanwhile, is strong stuff; their heavy beat creates an effect not unlike taking a punch to the face and a medicine ball to the chest while trying to walk out of quicksand. Many critics have desperately tried to excuse the lyrics, but like 2 Live Crew at their worst, the Geto Boys are hard to defend on any grounds except constitutional ones.

The rest of Texas rap falls between those two polarities. On To Hell and Back, the Dallas trio Nemesis shows off an appealing jazz-inflected extension of the hard-rap style popularized by Run-DMC and L. L. Cool J. So does Ron “C,” also of Dallas, whose “C” Ya entered the black charts in November 1989, at the same time he entered prison on drug charges. Although neither act shows much crossover potential, each scored moderate hits with the black audience on the first try.

Some observers predict that the acts that will endure will be those that incorporate raps in conventional songs, a la New Kids on the Block. That’s the route taken so far by Waco bubble gummers Hi-Five, which lost Toriano Easley, one of its original members, when he was arrested for murder and removed from the group three weeks after the release of its debut single, “I Just Can’t Handle It.” Hi-Five’s rhymes weave in and out of vocals reminiscent of the early Jackson Five. Houston’s Charles Shaw, who raps on Milli Vanilli’s “Girl You Know It’s True,” is cutting an album in Germany, where he has lived since 1978. His fifteen seconds of fame should help win him more of a hearing than most new acts get. Ms. Adventures, three sisters who grew up singing white gospel in Tyler, Dallas, and San Antonio before moving to Los Angeles a couple of years ago, sometimes lace their dance music with raps. They’ve had one minor hit in “Undeniable,” and they are pristine enough to ensure continued pop airplay, though it’s unlikely that they’ll ever find much acceptance from black fans.

In short, Lone Star rappers usually appear to be out of their element even when they’re successful. It’s one of the few areas of popular music where Texans are more followers than leaders—or, as has been heard at more than a few rap shows around the state, “Yo, y’all.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Music

- Hip-hop

- Carrollton